Maulik, Laya, Naya

Contents |

Maulik, Laya, Naya

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

A Dravidian caste of Manbhum and Western Bengal, who claim affinity with the Mal Pabari:is of Rajmahal, and who may possibly be an offshoot from that tribe, to whom, as being the earliest settlers in the country, the duty of propitiating the forest gods may easily have come to be assigned.

Internal structure.

The Maulik of Northern Manbhum and the Santal Parganas are divided into six sub-castes-Chandana, Hariyan or Jehariya, Mai oI' Mar, Sauriya, Rajbansi, and Deobansi. The last two groups call themselves Hindus, and allege that their ancestors were at one time in possession of the Pandra estate in Manbhum. The sections of all the sub-castes are totemistic. A man may not marry a woman belonging to his own section, nor one who falls within the usual formula for reckoning prohibited degrees.

Marriage

Adult-marriage was formerly in vogue among the Mauliks, as it is still among the Mundas and Oraons. Of arrulge. late years the example of the Hindus around them has led to the adoption of infant marriage ; and this practice, involving, as is ordinarily believed, an advance in social respectability, tends to become constantly more popular. The earlier custom. however, still survives, and sexual indiscretions before marriage are said to be not uncommon, and as a rule are leniently dealt with. After the bride has been selected and a small bride-price paid, the bridegroom is married to a mango• tree and the bride to a mahua.. This is followed by the ordinary ceremony performed under an open canopy made of sal leaves. The two Hinduised sub-castes employ a Brahman to recite mantras on this occasion; for the others a man of their own caste serves a priest. The binding portion is the marking of the bride's forehead with vermilion, which is done by the bride¬groom with the Janti or cutter used for slicing areca nut. Polygamy is not formally recognized, but a man is allowed to take a second wife if his first wife is barren. A widow may marry again by the sanga form, and is subject to no restrictions in her choice of a second husband. Great license of divorce is allowed, the tearing of a sal leaf in symbol of separat,ion being the only form required to complete the act. Divorced wives may marry again.

Religion

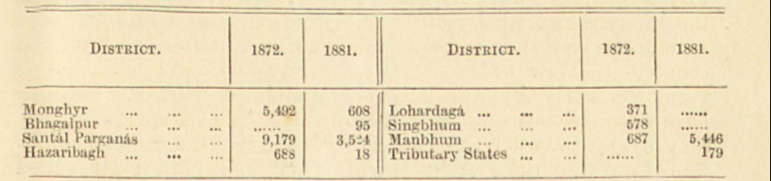

Although, as has been stated above, the Deobansi and Rajbansi sub-castes call in Brahmans of low rank, known locally as Panres, to assist in their marriage ceremony, even they have not yet taken to worshipping Hindu deities or employing Brahmans as then: family priests, and the caste as a whole still adheres to the rude animism characteristic of the aboriginal races of Western Bengal. Their offices as priests of the various spirtual powers who haunt the forests, rocks, and fields and bring disease upon man and beast are in great request. A Bhumij or a Kurmi who wishes to propitiate these dimly-conceived but potent influences will send for a Maulik to offer the necessary sacrifices in preference to a Leiya or priest of his own caste-a fact which speaks strongly for the antiquity of the settlement of the former in the country. Be ides serving as priests, they also collect lac, catechu, and other jungle produce, and work as cultivators and day-labourers. Their social rank, according to orthodox ideas, is exceedingly low, and no Hindu will take water from their hands. Mauliks them¬selves will eat boiled rice with Bhuiyas, and sweetmeats, etc., with S!1ntals and Mundas. The more advanoed Deobansi and Riljbansi sub-castes abstain from beef, and believe themselves to be thereby raised in ceremonial purity and social estimation above their fellows. It is curious to obs91've that while the non-Hinduised Mauliks will eat no one's leavings, the more orthodox sub-castes have no prejudices on this point so far as the members of the higher Hindu castes are concerned, and will eat the leavings of Brahmans, Rajputs, aud Kayasths. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Mauliks in 1872 and 1881 :¬