Barai

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Barai,Tamboli, Pansari

The caste of growers and ^" J. . sellers of the betel-vine leaf The three terms are used traditions. indifferently for the caste in the Central Provinces, although some shades of variation in the meaning can be detected even here—Barai signifying especially one who grows the betel- vine, and Tamboli the seller of the prepared leaf ; while Pansari, though its etymological meaning is also a dealer in pan or betel-vine leaves, is used rather in the general sense of a druggist or grocer, and is apparently applied to the Barai caste because its members commonly follow this occupation. In Bengal, however, Barai and Tamboli are distinct castes, the occupations of growing and selling the betel-leaf being there separately practised.

And they have been shown as different castes in the India Census Tables of 1 90 1, though it is perhaps doubtful whether the distinction holds good in northern India." In the Central Provinces and Berar the Barais numbered nearly 60,000 persons in 191 I. They reside principally in the Amraoti, Buldana, Nagpur, Wardha, Saugor and Jubbulpore Districts. The betel-vine is grown principally in the northern Districts of Saugor, Damoh and Jubbulpore and in those of Berar and the Nagpur plain. It is noticeable also that the growers and sellers of the betel-vine numbered only 14,000 in 191 1 out of 33,000 actual workers of the Barai caste; so that the majority of them are now employed in ordinary agriculture, field-labour and other avocations.

No very probable deriva- tion has been obtained for the word Barai, unless it comes from bdri, a hedge or enclosure, and simply means ' gardener.' Another derivation is from bardna, to avert hailstorms, a calling which they still practise in northern India. Pdn^ from the Sanskrit parna (leaf), is the leaf 1 This notice is compiled principally niukh, Deputy Inspector of Schools, from a good paper by Mr. M. C. Nagpur. Chatterji, retired Extra Assistant Com- missioner, Jubbulpore, and from papers ^ %\\&xx\r\g^Hindii Tribes a7id Castes, by Professor Sada Shiva Jai Ram, i. p. 330. Nesfield, B?-ief Viezv, p. M.A., Government College, Jubbul- 15. N.M^.P. Cens2is ReJ>ort (i^gi),^^ pore, and Mr. Bhaskar Baji Rao Desh- 3 1 7.

f^ar cxccllcna-. Ovviii^ to the fact that they produce what is [)crhaps the most esteemed luxury in the diet of the higher classes of native society, the Barais occupy a fairly good social position, and one legend gives them a Ikahman ancestry. This is to the effect that the first Barai was a Brfdiman whom God detected in a flagrant case of lying to his brother. His sacred thread was confiscated and being planted in the ground grew up into the first betel- vine, which he was set to tend. Another story of the origin of the vine is given later in this article.

In the Central Provinces its cultivation has probably only flourished to any appreciable extent for a period of about three centuries, and the Barai caste would appear to be mainly a functional one, made up of a number of immigrants from northern India and of recruits from different classes of the population, including a large proportion of the non-Aryan element. The following endogamous divisions of the caste have 2. Caste been reported : Chaurasia, so called from the Chaurasi divisions pargana of the Mirzapur District ; Panagaria from Panagar in Jubbulpore ; Mahobia from Mahoba in Hamirpur ; Jaiswar from the town of Jais in the Rai Bareli District of the United Provinces ; Gangapari, coming from the further side of the Ganges ; and Pardeshi or Deshwari, foreigners. The above divisions all have territorial names, and these show that a large proportion of the caste have come from northern India, the different batches of immigrants forming separate endo- gamous groups on their arrival here.

Other subcastes are the Dudh Barais, from dildh, milk ; the Kuman, said to be Kunbis who have adopted this occupation and become Barais

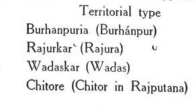

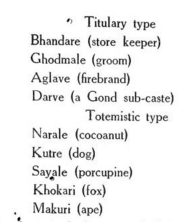

the Jharia and Kosaria, the oldest or jungly Barais, and those who live in Chhattlsgarh ; the Purania or old Barais ; the Kumhardhang, who are said to be the descendants of a potter on whose wheel a betel-vine grew ; and the Lahuri Sen, who are a subcaste formed of the descendants of irregular unions. None of the other subcastes will take food from these last, and the name is locally derived from lahuri, lower, and se^i or shreni, class. The caste is also divided into a large number of exogamous groups or septs which may be classified according to their names as territorial, titular and totemistic.

Examples of territorial names are : Kanaujia of Kanauj, Burhanpuria of Burhanpur, Chitoria of Chitor in Rajputana, Deobijha the name of a village in Chhattlsgarh, and Kha- rondiha from Kharond or Kalahandi State. These names must apparently have been adopted at random when a family either settled in one of these places or removed from it to another part of the country. Examples of titular names of groups are : Pandit (priest), Bhandari (store-keeper), Patharha (hail-averter), Batkaphor (pot-breaker), Bhulya (the forgetful one), Gujar (a caste), Gahoi (a caste), and so on. While the following are totemistic groups : Katara (dagger), Kulha (jackal), Bandrele (monkey), Chlkhalkar (from cJiikhal, mud), Richharia (bear), and others.

Where the group is named after another caste it probably indicates that a man of that caste became a Barai and founded a family ; while the fact that some groups are totemistic shows that a section of the caste is recruited from the indigenous tribes. The large variety of names discloses the diverse elements of which the caste is made up. 3. Mar- Marriage within the gotra or exogamous group and within riage. three degrees of relationship between persons connected through females is prohibited. Girls are usually wedded before adolescence, but no stigma attaches to the family if they remain single beyond this period.

If a girl is seduced by a man of the caste she is married to him by the pat, a simple ceremony used for widows. In the southern Districts a barber cuts off a lock of her hair on the banks of a tank or river by way of penalty, and a fast is also imposed on her, while the caste-fellows exact a meal from her family. If she has an illegitimate child, it is given away to somebody else, if possible. A girl going wrong with an outsider is expelled from the caste. Polygamy is permitted and no stigma attaches to the taking of a second wife, though it is rarely done except for special family reasons. Among the Maratha Barais the bride and bridegroom must walk five times round the marriage altar and then worship the stone slab and roller used for pounding spices.

This seems to show that the trade of the Pansari or druggist is recognised as being a proper avocation of the Barai. They subsequently have to worship the potter's

wheel. yVftcr the wedding the bride, if she is a child, goes as usual to her husband's house for a few days. In Chhattis- garh she is accompanied by a few relations, the party being known as Chauthia, and during her stay in her husband's house the bride is made to sleep on the ground. Widow marriage is permitted, and the ceremony is conducted accord- ing to the usage of the locality.

In Betul the relatives of the widow take the second husband before Maroti's shrine, where he offers a nut and some betel-leaf. He is then taken to the mrdguzar's house and presents to him Rs. 1-4-0, a cocoanut and some betel-vine leaf as the price of his assent to the marriage. If there is a Dcshmukh ^ of the village, a cocoanut and betel-leaf are also given to him. The nut offered to Maroti represents the deceased husband's spirit, and is sub- sequently placed on a plank and kicked off by the new bridegroom in token of his usurping the other's place, and finally buried to lay the spirit. The property of the first husband descends to his children, and failing them his brother's children or collateral heirs take it before the widow.

A bachelor espousing a widow must first go through the ceremony of marriage with a swallow-wort plant. When a widower marries a girl a silver impression representing the deceased first wife is made and worshipped daily with the family gods. Divorce is permitted on sufficient grounds at the instance of either party, being effected before the caste committee or panchdyat. If a husband divorces his wife merely on account of bad temper, he must maintain her so long as she remains unmarried and continues to lead a moral life.

The Barais especially venerate the Nag or cobra and 4^ Reii- observe the festival of Nag-Panchmi (Cobra's fifth), in con- foc^af" nection with which the following story is related. Formerly status. there was no betel -vine on the earth. But when the five Pandava brothers celebrated the great horse sacrifice after their victory at Hastinapur, they wanted some, and so messengers were sent down below the earth to the residence of the queen of the serpents, in order to try and obtain it.

Basuki, the queen of the serpents, obligingly cut off the top The name of a superior revenue officer under the Marathas, now borne as a courtesy title by certain families.

joint of her little finger and gave it to the messengers. This was brought up and sown on the earth, and pan creepers grew out of the joint. For this reason the betel-vine has no blossoms or seeds, but the joints of the creepers are cut off and sown, when they sprout afresh ; and the betel-vine is called Nagbel or the serpent-creeper.

On the day of Nag- Panchmi the Barais go to the bareja with flowers, cocoanuts and other offerings, and worship a stone which is placed in it and which represents the Nag or cobra. A goat or sheep is sacrificed and they return home, no leaf of the pan garden being touched on that day. A cup of milk is also left, in the belief that a cobra will come out of the pan garden and drink it. The Barais say that members of their caste are never bitten by cobras, though many of these snakes frequent the gardens on account of the moist coolness and shade which they afford. The Agarwala Banias, from whom the Barais will take food cooked without water, have also a legend of descent from a Naga or snake princess. '

Our mother's house is of the race of the snake,' say the Agarwals of Bihar.

The caste usually burn the dead, with the ex- ception of children and persons dying of leprosy or snake- bite, whose bodies are buried. Mourning is observed for ten days in the case of adults and for three days for children. In Chhattlsgarh if any portion of the corpse remains unburnt on the day following the cremation, the relatives are penalised to the extent of an extra feast to the caste-fellows. Children are named on the sixth or twelfth day after birth either by a Brahman or by the women of the household. Two names are given, one for ceremonial and the other for ordinary use. When a Brahman is engaged he gives seven names for a boy and five for a girl, and the parents select one out of these.

The Barais do not admit outsiders into the caste, and employ Brahmans for religious and ceremonial purposes. They are allowed to eat the flesh of clean animals, but very rarely do so, and they abstain from liquor. Brahmans will take sweets and water from them, and they occupy a fairly good social position on account of the important nature of their occupation. ^ Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. Agarwal.

" It has been mentioned," says Sir 1 1. Rislcy,' " that the s- Occupa- garden is regarded as ahnost sacred, and the superstitious practices in vogue resemble those of the silk-worm breeder. The Bfirui will not enter it until he has bathed and washed his clothes. Animals found inside are driven out, while women ceremonially unclean dare not enter within the gate.

A Bnlhman never sets foot inside, and old men have a pre- judice against entering it. It has, however, been known to be used for assignations." The betel-vine is the leaf of Piper betel L., the word being derived from the Malayalam vcttila, ' a plain leaf,' and coming to us through the Portuguese detre and bet/e. The leaf is called pan, and is eaten with the nut of Areca catechu, called in Hindi supari.

The vine needs careful cultivation, the gardens having to be covered to keep off the heat of the sun, while liberal treatment with manure and irrigation is needed. The joints of the creepers are planted in February, and begin to supply leaves in about five months' time. When the first creepers are stripped after a period of nearly a year, they are cut off and fresh ones appear, the plants being exhausted within a period of about two years after the first sowing.

A garden may cover from half an acre to an acre of land, and belongs to a number of growers, who act in partnership, each owning so many lines of vines. The plain leaves are sold at from 2 annas to 4 annas a hundred, or a higher rate when they are out of season. Damoh, Ramtek and Bilahri are three of the best- known centres of cultivation in the Central Provinces. The Bilahri leaf is described in the Ain-i-Akbari as follows :

" The leaf called Bilahri is white and shining, and does not make the tongue harsh and hard. It tastes best of all kinds. After it has been taken away from the creeper, it turns white with some care after a month, or even after twenty days, when greater efforts are made." ^ For retail sale btdas are prepared, consisting of a rolled betel-leaf containing areca-nut, catechu and lime, and fastened with a clove. Musk and cardamoms are sometimes added. Tobacco should be smoked after eating a bida according to the saying, ' Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. 72, quoted in Crooke's Tribes and Barui. Castes, art.

Tamboli.

Bloclimann, Ain-i-Ahbari, i. p.

' Service without a patron, a young man without a shield, and betel without tobacco are alike savourless.' Bidas are sold at from two to four for a pice (farthing). Women of the caste often retail them, and as many are good-looking they secure more custom ; they are also said to have an indiffer- ent reputation. Early in the morning, when they open their shops, they burn some incense before the bamboo basket in which the leaves are kept, to propitiate Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth.

Barai: Deccan

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Origin

Barai, Tamboli — a caste of betel vine growers and betel leaf sellers, found in the Sirpur and Rajura Talukas of the Adiltbad District. The two terms, although used indifferently as the names of the caste, disclose some shades of variation in the meaning, Barai, signifying one who grows the betel vine, and Tamboli, the seller of the prepared leaf. The following passage, quoted from the Central Provinces Ethnographic Report, may throw some light upon the origin of the caste. " No very probable derivation has been obtained for the word Barai, unless it comes from bdri, ' a hedge or enclosure,' and simply means ' gardener.' Another derivation suggested is from barana, ' to avert hail storms,' a calling which they still practise in Northern India. Owing to the fact that they produce what is perhaps the most esteemed luxury in the diet of the higher classes of Indian society, the Barais occupy a fairly good social position and the legend gives them a Brahman ancestry. This is to the effect that the first Barai was a Brahman, whom God detected in a flagrant case of lying to his brother. His sacred thread was confiscated and, being planted in the ground, grew up into the first betel vine, which he was set to tend. "

Internal Structure

In the Central Provinces the caste is very numerous and is broken into several sub-castes, mostly of the territorial type. The number of Barais in these Dominions being limited, they have no endogamous divisions ; but their exogamous sections are numerous and of different types, as illustrated below : — Territorial type

From the mixed character of their exogamous sections it may appear that the caste is mainly a functional group, made up of a number of immigrants from Northern India and of recruits from different classes of the population, including a large proportion of the non- Aryan element.

A man cannot marry a woman belonging to his own section. the section names go by the male side, the rule prohibiting marriage within the section is supplemented to the extent that a man cannot marry any of his first cousins. A man may marry two sisters; but the rule in this case is that he must marry the elder first.

Marriage

Girls are married before they attain the age of puberty, usually between five and ten years. Polygamy is per- mitted. In theory, a man may marry as many wives as he can afford to maintain ; in practice, however, he rarely takes more than two.

The marriage ceremony is of the type in use among other local castes, especially among Khaira Kunbis. The following are the important stages comprising it : —

1 . The worship of Mari Ai, or the goddess of cholera, with

offerings of goats. This is done by both parties, each in their own house.

2.The worship of Devak, which consists of the mango and saundad {Prosopis spicigera) leaves, and of two big and twelve small earthen gots brought ceremonially from the potter's house.

3.The bridal procession : — The bridegroom goes in proces- sion, accompanied by his friends,' relatives and neigh- bours, to the bride's village where; on arrival, he is formally received by the parents of the bride and lodged in a house known as janvasa

4.Antarpat : — At a lucky moment, fixed for the wedding, the bridal pair stand facing each other in front cf the bohold (earthen platform) under the wedding booth. A curtain is held between them and the officiating priest, who is a Brahman, recites mantras, wjiile the assembled people throw rice, coloured with turmeric, on' the couple. The antarpdt is removed and the Brahman fastens their garments in a knot and ties konkonum or thread bracelets on their wrists, at the same time putting a string of black beads (mangal sutra) round the bride's neck. This is deemed to be the binding and essential portion of the ceremony.

5.Tamhord: — The bridal pair are seated on the bohoJd and

married females, whose husbands are living, _touch th^

feet, knees and shoulders of the pair with their fingers, holding at the same time a mango leaf and yellow rice in their hands. Dhenda, as described under Dhanojia Kunbis, is performed and the bridal pair return in procession to the bridegroom's house.

Barais allow a widow to marry again and do not require her to marry her late husband's younger brother or any other relative. The marriage ceremony is of the type common among other castes of the locality. An areca nut is offered to Maruti, representing the deceased

husband's spirit, and is subsequently placed on a low wooden stool and kicked off by the new bridegroom in token of his usurping the other's place ; the nut* is finally buried to lay the dead husband's spirit.

The bridal pair are then seated side by side and their garments are tied in a knot. The bride is presented with a new sari, new bangles are put on her wrists and a spot of \unkum or red aniline powder is made oh her forehead. This concludes the ceremony.

The widow forfeits all claims to her late husband's property.

A bachelor marrying a widow must first go through the cere- nipny of marriage with a mi plant (Calotropis gigantea). Wh widower marries a virgin, a silver impression, representing the deceased first wife, is made and worshipped daily with the family gods. Divorce is permitted with the consent of the caste Panchayat (council) on the ground of the wife's adultery, or if the couple do 'not agree. If a- husband divorces his wife merely on account of bad temper, he must maintain her so long as she remains unmarried and continues to lead a moral life.

Religion

In matters of religion, the Barais follow the usages of all orthodox Hindus. Their favourite deity is Kurbhan, adored inVhe form of an idol made of sandalwood. Ancestral worship is "in strong force and silver impressions, representing the departed ancestors, are placed among the family gods and worship- ped every three years with offeriflgs of goats and fowls. Reverence is also paid to the animistic deities of Pochamma and Mari Ai. Greater gods, such as Balaji, Anant, Shiv and his consort Gouri, are worshipped under the guidance of Brahmans, who serve them as priesta on all ceremonial and religious occasions, and act as their spiritual advisers (gurus).

According to the Barais themselves, their special and charac- teristic deity is the Nag, or cobra, in whose honour the festival of Nag Panchmi is observed every year. The following story related in this connection deserves nntention * : —

"Formerly there was no betel vine on the earth. But when the five" Pandava brothers celebrated the great horse sacrifice after their victory at Hastinapur, they wanted some, and so messengers were sent down below the earth to the residence of the queen of the serpents in order to try and obtain it. Basuki, the king of the serpents, obligingly cut off the top joint of his little finger and gave it to, the messengers. This was brought up and sown on the earth and pan creepers grew out of the joint. For this reason, the betel vine has no blossoms or seeds, but the joints of the creepers are cut off'and sown, when they sprout afresh, and the betel vine is called Nagbel or the serpent creeper. <Dn the day of Nag Panchmi (the fifth of the light half of Shravana). the Barais go to the bureja wish flowers, cocoanuts and other offerings, and worship a stone which is placed in it and which represents the Nag or cobra. A goat or sheep is sacrificed and they return home, no leaf of the pan garden being touched on that day. A cup of milk is also left in the belief that a cobra will come out of the pan garden and drink it."

The Barais say that the members of their caste are never bitten by the cobra, though many of these snakes frequent the betel gardens on account of the moist coolness and shade which 4hey afford.

Disposal of the Dead

The dead are burned in a lying posture with the head pointing to the south. Bodies'of unmar- ried persons, of lepers, and of those who died of smallpsx, cholera, or snake-bite, are buried. The ashes and bones are collected on the tenth day after death and thrown into a river or stream. On the same day, Srddha is performed for the benefit of the soul of the deceased, to whom seven balls of wheaten flour are offered and subsequently thrown into a stream or tank. Mourning is observed for ten days for adults and for three days for children. Anqestors in « general are propitiated in the months of Vaishakh and Bhadrapad.

Social Status

In point of social standing the Barais rank a little above the Maratha Kunbis and eat food cooked only by a Brahman, while Maratha Kunbis and Kapus take food cooked by a Barai. The members of the caste eat the flesh of fowl, fish, deer, goat and hare and drink fermented liquors.

Occupation

The chief and characteristic occupation of the caste is the growing of the pan plant or Piper Betle. Of late years some have taken to trade, while others are found in Government service. The Barais also sell betel leaves and usually employ women for this purpose. Pan leaves are sold at from 1 to 2 annas per hundred, or at a higher rate when they are out of season. For retail sale, bindas are prepared, consisting of rolled betel leaves containing areca or betel nut, quick lime and catechu, and fastened with a clove. These are sold at from 1 to 2 for a pice.

The pan vine fs very delicata and requires careful cultivation. The pain gardens (Pan Maids) are treated liberally with manure and irrigated. The enclosure, generally eight feet high, is sup- ported by pangra (Erythrina indica) and nim (Melia indica) trees. The sides are closely matted with reeds to protect the interior from wind and the sun's rays. Care is taken to drain off the rain as it falls, it being essential for the healthy growth of the plants that the ground is kept dry. The joints of the creepers are planted in June- July and begin to supply leaves in about five or six months' time. The plant being a fast growing one has its shoots loosely tied with grass to upright poles supplied by pangra (Erythrina indica) and shevri {Sesbania agyptiaca) trees, while every year it is drawn down and coiled it the root. Weeds are carefully eradicated. Pan leaves are plucked throughout the year, but are most abundant in September and October, while a garden, if carefully looked after, continues productive for from 8 to 10 years.

A Pan Mala is regarded as sacred by the growers, and women, when ceremonially unclean, are not allowed to enter it ; animals found inside are driven out. At the present day the castes that are engaged in rearing the betel vine in these Dominions are Tirgul Brahmans, Ful Malis, Binjiodes and Lingayits.