Mrung

Contents |

Munchi

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Rishi,l the leather-dressing and cobbler caste of Bengal, by origin doubtless a branch of the Chamars, though its members now repudiate that name and claim to be a distinct caste of somewhat higher social position. Mr. Nesfield observes that" the industry of tanning is preparatory to, and lower than that of, cobblery: and hence '" '" '" 'if the caste of ChamaI' ranks deoidedly below that of Muchi. The ordinary Hindu does not consider the touch of a Muchi so impure as that of a Chamar, and there is a Hindu proverb to the effect that 'dried or prepared hide is the same thing as cloth,' whereas the touch of the raw hide before it has been tanned by the ChamaI' is considered a pollution. The Muchi does not eat carrion like the Chamar, nor does he eat swine's flesh; nor does his wife over practise the much-loathed art of midwifery. He makes the shoes, leather aprons, leather buckets, harness, portmanteaux, etc., used by the people of India. As a rule he is much better off than the Chamar, and this circumstance has helped amongst others to raise him in the social scale." It may be gathered from this description that in the North-West Provinces the Muchi never dresses freshly-skinned hides, but confines himself to working up leather already tanned by the ChamaI'. This distinc-tion does not appear to be so sharply drawn in Bengal, where Muchi tan hides like the Chamars, but will only cure those of the cow, goat, buffalo, and deer.

Traditions of origin

The origin of the Muchi oaste is given in the following legend, related to Dr. Wise by one of their Brahmans, and afterwards reported to me substantially in the same form from an independent source :-One of the Praja-pati, or mind-born sons of Brahma, was in the habit of providing the flesh of cows and clarified butter as a burnt offering (Ahuti) to the gods. It was then the .custom to eat a portion of the sacrifice, restore the victim to life, and drive it into the forest. On one occasion the Praja-pati failed to resuscitate the sacrificial animal, owing to his wife, who was pregnant at the time, having clandestinely made away with a. portion. Alarmed at this he summoned all the other Praja-patis, and they sought by divination to discover the cause of the failure. At last they ascertained what had occurred, and as a punishment the wife was cursed and expelled from their society. The child which she bore was the first Muchl, or tanner, and from that time forth mankind being deprived of the power of reanimating cattle slaugh-tered for food, the pious abandoned the practice of killing kine altogether. Another story is that Muchirem, the ancestor of the custe, was born from the sweat of Brahma while dancing. He chanced to offend the irritable sage Durvasa, who sent a pretty 1 Buchanan met with a tribe of fishermen in Puraniya ealled Rishi, and con idel'ed them to be an aboriginal tribe of Mitbila.. Rishi, however, is often used as a pseudonym to hide the real paternity of a caste: thus the Mu ahar often calls himself "Hi hi.bulaka," or son of a Rishi, and the Bengali Cham{u' tries to pass incognito as a Rishi. In the case of the Musahar it is pos ible that Rishi may be l'tikhi or Rikh-Muu, the bear, one of the original totems of the Bhuiya. or Musahar tribe, and the arne may hold good for the Chand6.1. This explanation, however, is mainly eonjecttu'al. Brahman widow to allure him into a breach of chastity. Muchiram a~costed the widow as mother, an~ refu ed to have anything to do wlth her; but DUl'vasa used the mlraculous powers he had acquired by penanoe to render the widow pregnant, so that the innocent Muchiram was made an outcaste on suspioion. From the widow's twin sons Bara l~am and Uhhota Ram desoended the Bara-bhagiya and Chh ota-bhagiya sub-oastes, which are the two main divisions of Muohis at the present day. The Chhota-Bhagiya deal in hides act as musioians, and do various kinds of leather work; while the Bara-bhagiya profess to be only cultivators. The latter are again divided into Uttar-Rarh i and Dakin-Rarhh i, who do not intermarry or eat together. The other sub-oastes, Chasa-Kurur or Chasa-Kolai, are agrioulturists; the Betua make cane baskets and also cultivate; the Jugi-Much i or Kora weave coarse cloth of cotton often mL"'{ed with silk; the Tikakar Konai, who make the tika or charooal balls used for lighting pipes; and the Baital, Kurur, Mala bhumia, Sabarkara, and Sanki, are shoemakers, cobblers, and curriers. Muchis have only two sections, K.asyapa and Sandilya, which have been borrowed from the Brahmamcal system, and has no bearing upon the prevention of intermarriage between near relatives.

Marriage

They follow the ordinary rules as to prohibited degrees, and permit the marriage of two sisters to the same man, provided that the younger is not married first. Both infant and adult-marriage are recognized for girls, but the former practice is deemed the more respectable, and. is resorted to in the large maJority of cases. In the Dacca distnct a father generally receives from fifty to sixty rupees for his daughter, from which it may be inferred that the custom of polygamy has tended on the whole towards the preponderance of males in the caste. III other districts, however, the bride-price is not so high, and in Pabna it is said to vary from Rs. 5 to Rs. 25-4, according to the means of the bridegroom. The marriage ceremony is a simplified form of that in use among the higher Hindu castes; sindurdan, or according to some the burning of klvli or parched paddy before the bride and brideo-room. being the binding portion. the bride is dressed in red garments. .In former years, says Dr. Wise,. the marriage ceremonies of the Rishi were scenes of debauchery and intemperance, but of late intoxicating liquors have been prohibited until all the regular forms have been observed. Even Hindus, who rarely have anything favourable to say of the Rishi, confess that now-a-days, owing to some unknown cause, both the Chamars and Risbis have become more temperate and more attentive to their religious duties than formerly. Polygamy is permitted with no restriction on the number of wives, except the man's ability to maintain them and their children. Divorce is permitted on the ground of adultery. Usually the panchayat of the caste are called. Together by their president (paramanik or moiali ) to give their sanction to the proceedings; an.d If thiS lS not done at the mstanc~ of the husband, the wife has a night to appeal to the panchayat. With the permission of that body divorced wives may marry again by the sanga or nika form. Widows also may marry a second time by this ritual, the binding portion of which consists of exchanging garlands made. of the flowers of the tulsi (Ocymurn sanctum). Here also the sanctlon of the panchayat is required, and a feast is given to the members. A small sum, varying from Re. 1 to Rs. 5, is paid as pan. Indica¬tions are not wanting that the opinion of the caste tends to condemn widow-marriage, and that the custom may be expected to die out within a generation or two unless some special influence is brought to bear in its favour. Already some Muchis hold that only virgm widows can properly marry again, and that the remarriage of a full-grown woman who has already lived with her husband is little better than concubinage. The children of sanga marriages are deemed to be iu some sense degraded, and, if males, have to pay a heavy fine before they can obtain wives. Like Bam'is and Bagdis, the Muchis admit into their community members of any caste higber than their own. The new member is required to give a feast to the caste panchayat, and to eat with them in token of fellow¬ship. Instances of men of other castes thus becoming Muchis are rare, and occur only when a man has been turned out of his own caste for having intercourse with a Muchi woman and taking food from her hands.

Religion

The majority of the caste are believed to belong to the Saiva sect, but a large proportion of the Betua sub¬ caste are Vaishnavas. They imitate the Sudras in most of their religious ceremonies, while others peculiar to themselves resemble those of the Chamars. 'flough regarded as utterly vile, tbey are permitted to make offerings at the shrines of Kali, which a Jugi is not allowed to do. They keep many Hindu festivals, the chief being that in honour of Viswakarma on the last day of BMili•a. When small-pox prevails they offer a pig to Sitala, first of all smearing the animal's snout with red lead and repeating certain incantations, after which it is set free, and anyone can seize it. Like the Chamar, DhoM, Dosadh, and other low castes, the M uchis worship Jalka Davi whenever cholera or other epidemic eli. case breaks out. 'The Muchi women, however, only collect con¬i ributions in their own quarter, and wear the wreath of plantain, date palm or bena (Andropogon muricatus )for two and a half days instead of for six, as is the custom of the Chamars. Muchiram Das, the reputed ancestor of the caste, and Rui Das, are also popular objects of worship.

Priests

A Brahman was bestowed on the Bara-bhagiya Muchis by Ballal Sen, and the story goes that in the palace of that monarch a certain Brahman, having made himself especially troublesome by insisting upon being appointed as priest to one of the newly-formed castes, had it intimater! to him by the Haja that he would belong to the caste which should first appear to him in the morning. There was also a Muchi, a celebrated player on the naqal'ah, or kettledrum, whose duty it was to sound the j•e/leille. It was easily arranged that the Brahman should first cast his eyes on him when he awoke, and his descendants have ever since ministered to this despised race. They rank amollg the lowest (If the Barna-Brahmans, and neither members of the g sacred order nor mon belonging to the A'charnl1i castes will take water from their hands. The Chhota-bhagiya have pnests of their own. Muchis burn their dead and prrform iil"uddh on the thirtieth day after death. In the case of men who have died a violent death there is no sraddh, but a prayaschitta, or expiatory ceremony, is performed. The Chhota-bhagiya and Betua sub-castes, like the Chandals, observe ten days of impurity and celebrate the srriddh on the eleventh.

Social status

The social position of Muchis is, as has been intimated above, perhaps a shade higher than that of Chamars, but this is not saying much, and both castes may properly be placed in one class at the bottom of the scale of precedence recognized by the average •Hindu. None of the regular village servants will defile himself by working for a Muchi, and thus the caste has been compelled to provide itself with barbers and washermen from among its own members. Illegitimate children are usually brought up to these professions, and wherever the community is a large one no inconvenience is felt. Their rules regarding diet are in keeping with their standing in society. The Chhota.bhagiya sub-caste eat beef, as the Chamars do; are very partial to chickens. and regard pork as a delicacy. The Bara-bhagiya, Betua, and Chasa-kolai ab tain from beef and pork, but not from fowls; and they are far less partioular than the higher castes as to the kinds of fish which the eat. Like the Chamars, all Muchis are great spirit-drinkers, and notorious for their indulgence in the more dangerous vice of ganja-smoking. No other caste will eat food prepared by fI. Muchi. but Dams will take water £rom their hands and will smoke from the same hookah.

Occupation

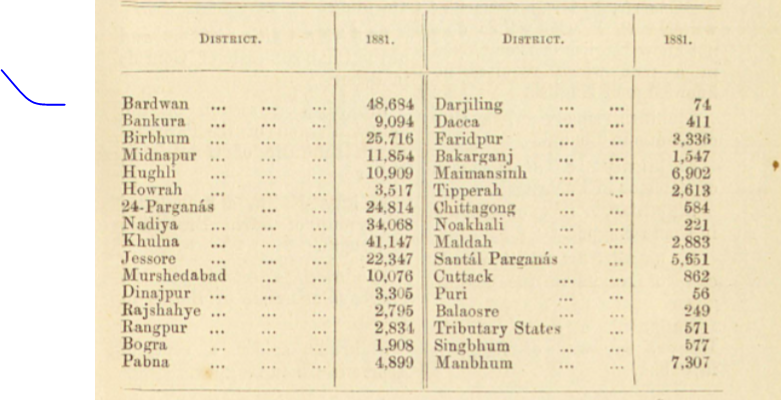

Muchis work as tanners, shoe-makers, saddlers, musicians, and basket-makers. Their mode of preparing skins is as follows :-The raw hide is rubbed, and then soaked for fifteen to twenty days in a strong solution of lime. It is then deprived of its hair and of any fat that remains, and steeped for six days in acid tamarind juice. Finally, it is put in a vat containing a solution of lac and pounded babul (Acacia), garan (Ceriops Roxburghianlls) , and sundar! (lleritiera minD?') barks, the hide being after this immersion regarded as properly cured. The town Muchis buy hides £rom their brethren resident in those parts of the country where cattle abound. The village Muchis of the Chhota-bbagiya sub-caste, while they pride themselves on not skin-ning the carcasses of their own cattle, row up and down the rivers in their neighbourhood in search of carcasses, and when epidemic diseases attack the herds they find so much to do that the villagers attribute the spread of the disease to them. It is doubtless often the case that they puncture a healthy cow with an Acacia thorn impregnated with virus, but they are rarely, if ever, detected at this villainous trade. The people, however, firmly believe that they increase their profits in this way. In Western Bengal and Chota Nagpur, where the sal jungles form the chief pasturing grounds, Muchis destroy cattle with arsenic rolled up in a bundle of mahua petals. These are a favourite food for cows, and can be strewn on the ground without rousing any supicion. The Muchi will not touch a corpse, but will skin the caroass of a dead animal. The skin of the buffalo sacrificed at the Durga Pllja is their perquisite, and the skinning of the animal often gives rise to bitter quarrels between rival families. Most Muchis make shoes, but of inferior quality to those manufactured by the Chamars. The Betua. sub-caste are famous for making baskets with rattan (Oalamus 1"otang) , which natives assert are so closely woven that they will hold water. They also collect the roots of the dub grass (Panicwn), and manufacture the brush (man Jan) used by weavers for starching the warp. In some parts the Muchi castrates bull calves, but this they stoutly deny. Others, again, work as sweepers and remove night-soil, but those who do so are excluded from intermarriage with the rest of the caste, and appear to be on the way to form a sub-caste of their own. The tabla-wala, or drum-maker, is always a Muchi. Goats' j skins are used for the covering, while cows' hides supply the strin S rl for tightening the parchment. On every native drum, at. one l;:i~i both ends, black circles (khiran) are painted to improve the pitc ~c~(9 The Muchi prepares a paste of iron filings and rice, with which he stains the parchment. Ai; all Hindu weddings they are employed at;;; musicians, and engaged in bands, as among Mubamadans. Their favourite instruments are drums of various shapes and sizes, the violin, and the pipe. The female Muchi differs from the ChamMn in never acting as a midwife, in wearing shell bracelets instead of huge ones of bell-metal, and in never appearing as a professional singer. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Muchis in 1881, the figures for 1872 having been included with those of Chamars :¬