Konkani cinema

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

1950-2015

The Times of India Dec 21 2015

Lisa Monteiro

With Nachom-ia Kumpasar making it to the Oscars' inital shortlist this year, and 20 movie releases in the last five years, the industry has got a new lease of life As L'Immagine Ritrvata, a restoration laboratory in Bologna, Italy, breathes life into one of the few surviving reels of the first-ever Konkani film, the 1950 hit Mogacho Aunddo (Love's Craving), the industry itself has found a new lease of life. With Nachom-ia Kumpasar (Let's Dance To The Rhythm) making it to the initial list of 305 movies for the 88th Academy Awards this year, Konkani cinema is on an all-time high. The movie has been running to full houses and is on every true-blue Goan's mind.

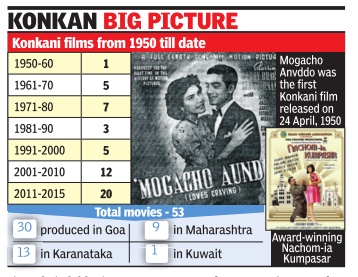

There was a time when one Konkani release in two years was a big deal. But the last two years have seen a transformation. Five Konkani films released in 2014 and three came out this year, with one more, Home Sweet Home 2, scheduled for a December 25 release.Of the 53 Konkani films produced since 1950, as many as 30 have been produced in Goa.

While director Rajendra Talak believes Konkani films should be released in multiplexes, most filmmakers in Goa are shunning commercial releases and choose to screen their movies at the two Ravindra Bhavans in Margao and Vasco, and at Entertainment Society of Goa (ESG) in Panaji. “The commerce of releasing a Konkani film for a popula tion of six lakh cinema-goers in a multiplex is lopsided. Instead of a two-week glory , we decided that we wanted to keep our film alive for two years. So we used the existing government venues, supplementing them with Dolby speakers wherever required,“ said Bardroy Barretto, the director of Nachom-ia Kumpasar.

For Talak, who has 30 years of experience in theatre, it was the announcement of the first International Film Festival (Iffi) in Goa in 2004 that motivated him to make a movie. He couldn't fathom a film festival in the state that didn't have a single Konkani film to boast of.His first celluloid film was Aleesha, which premiered at Iffi that year. Film critic Sachin Chatte too feels that it is this film festival, held in the state for 12 years in a row, that is inspiring Goans to make good films. After Amchem Noxib (Our Fate) and Nirmon in 60's, Konkani cinema didn't have anything worthwhile to boast of for four decades. In the past five years alone, 20 films have hit the screens.Chatte looks at this post-Iffi spurt as a second coming of Konkani cinema.

Filmmaker Laxmikant Shetgaonkar believes the digital age has enabled smaller filmmakers to make a movie at half the price of a traditional celluloid film. Konkani films, he believes, shouldn't be restricted by their language.“If you restrict your film to a Konkani-speaking audience, it's difficult to recover costs.Instead, a filmmaker can make the aesthetics of the film work so that it evokes an emotional response from an universal audience,“ he says.Shetgaonkar's 2009 celluloid film Paltodcho Munis (Man Beyond the Bridge) received recognition in the state only after it won the FIPRESCI prize at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Made with a budget of about Rs 4.25 crore, Barretto's Nachom-ia Kumpasar, released in 2014, is a story of two Goan azz musicians. Barretto chose to record the film's music with a live band to give it an organic touch.“We didn't want to promote it or promise too much.We just let the film do the talking,“ says Barretto.

Today the film is in contention for the best foreign film and best background score in the Oscars' initial shortlist. It has already won two National Awards and has travelled widely to several international film festivals. Barretto hopes to make the film reach a wider Konkani-speaking audience. “We will break even eventually ,“ he says.

Not many Konkani films have survived the test of time.Of the old films, copies of only two -Jivit Amchem Oxem (1971) and Boglantt (1975) -are found at the National Film Archive of India, says Konkani writer and film researcher Isidore Dantas, explaining, “Back then, producers needed money and sold the reels to distributors who were not interested in preserving them.“

Financing films is still a big problem. Filmmakers require schemes to help with production and promotion costs. On the other hand, Barretto feels the state needs proper infrastructure at various venues to screen films. He also believes that the industry can't afford to be averse to professionals from outside the state. “Filmmaking is very competitive. We have to be open to learn. Many of us gained our skills in Mumbai.“