Panchal: Deccan

Contents |

Panchal

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

(Titles :— Mar. Naik. Potdar, Rao.)

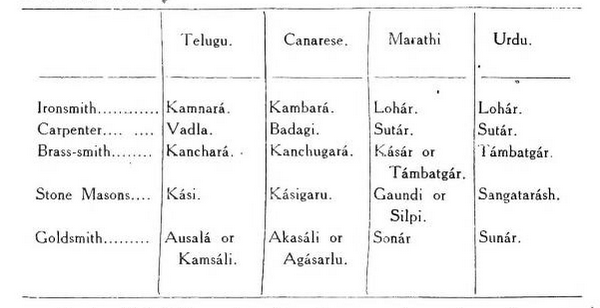

Panchal, Panchadayi, Punyavachan, Kamsale (Telugu), Kammalan, Acharji — a numerous caste which comprises the five artisan classes of the Dominions whose names, with their equivalents in Telugu, Canarese, Marathi and Urdu, >are mentioned in the following table ; —

In the Maharashtra these five classes are becoming endogamous, but in the Carnatic and Telingana they are merely occupational divisions, there being no restriction preventing intermarriages or interdining among them, or disallowing a ihan from following more than one occupation or changing his" sub-division.

Origin

The physical characteristics, the invariably dark com- plexion and rough features of the Panchals, appear to mark them as of South India origin. This view derives strong support from the fact that the members of the caste carefully taboo the fruit of the Phanas tree (Jack) neither eating, plucking, cutting nor injuring the tree in any way. The Panchalas are even believed to have originally borne the name of the tree, although at the present day they have dropped it altogether. Regarding their origin, various traditions are current. According to one they claim to be descended from five 'Brahma Rishis ' (divine sages), Manu, Maya,* Twashta, Silpi and Daivadnya, who sprung from thfe five faces of Vishwakarma (lit. the aeator of the universe) the celestial architect of the gods. From Manu — the diviae ironsmith, descended the Kamnara class, from Maya, the Vadlas, or carpentws, from Twashta, the Braziers, or Kan- charas, from Silpi Rishi, the stone-cutters and from Daivadnya, the Ausalas, or goldsmiths. Another story states that the above named Rishis, the progenitors of the Panchal caste, came out of Siva's five* mouths, viz., Sadyojat, Wamadeo-, Aghor, Tatpurusha and Ishana and that Manu married Kanchana, daughter of Angira Rishi; Maya's jwife was Sulochana, daughter of Psrashara; the wife of Twashta was Jayanti, daughter of the sage Koushika; Bhrigu's daughter Karuna was the wife of Silpi and the last, Daivadnya, was married to Chan- drika, daughter of the great sage Jai'mini (Skanda Purana, Nagar Khanda). A third tradition says that Prabhas, son of Prajapati and grandson of Pitamaha Muni, had a son with five mouths and ten hands, called Vishwakarma, to whom were born the five mythical ancestors of the Panchal caste.

As the progeny of Vishwakarma, the Panchals call themselves Vishwa Brahmins, deny the sacerdotal authority of Brahmins and employ their own Pandits as priests to conduct their religious ceremonies. They go so far as to assert that they are superior even to Brahmins in origin, for whereas the lalier are descended from Rishis of mongrel tribes, they themselves can claim a divine parentage, being sprung from Brahma Rishis, born of the god Vishwakarma. This advancing courage of the Panchals to claim superiority over all existing castes has occasioned many riots and led to many a case in the law courts. It will not be therefore out of place to review, in brief, the grounds on which the Pan- chalas base their claims of superiority to the rest of the community. These grounds are: — (1) Decisions in courts of justice, (2) some sentences in the Vedas, (3) certain passages from the Mula Stambha and the Silpa Shastra (two works on architecture), the Vajra Suchi and Kapildwipa (two Budhist controversial books on the abolition of caste) and the poems of Vemana, a Telugu Shudra poet. The "decisions in courts" merely state that Panchals (Tamil, Kama- lans) are to be allowed to perform such rites as they choose without molestation. As to the Vedas it is not only the Panchalas who can quote scriptures for their purpose, and these writings were, moreover, compiled long before the present caste system originated, so that chance sentences in them are of little weight in the controversy. The other books adduced in evidence are not authoritative or sacred works.

"There can be no doubt that the Panchala's claim is of com- paratively recent origin. The inscriptions of 1013 A.D., referred to in paragraph 464 of the 1891 Census Report, show that at that time they had to live outside the villages in hamlets of their own like the Paraiyans and other low castes and a later translation (South Indian Inscriptions, Vol. Ill, Part 1, page 47) gives an order of one of the Chola kings that they should be permitted to blow conches and beat drums at their weddings and funerals, to wear sandals and to plaster their houses, and so shows, by implication, that these luxuries were previously denied to them. The stone-masons are spoken of in the inscriptions as ' Silpachari,' but the stone sculp- tors had, some of them, to carve images of gods, and so earned a certain degree of recognition, and ' silpachari ' may only mean a sculptor. At the present day other Shudras do not treat them as Brahmnis, neither accepting food nor water from their hands nor calling them in as Purohits at their religious ceremonies." (Madras Census Rep>ort, 1901, page 166.)

It should be observed, however, that this movement towards elevation has been set on foot by the wealthy and learned members of the community, while the lower strata are still plunged in utter ignorance, regulate their marriages by family surnames, indulge in flesh and wine and employ Brahmins at their religious ceremonies. Many of these latter do not even wear the sacred thread. It may be that, in course of time, the more advanced and educated Pan- chalas will form themselves into an independent caste.

Internal Structure

The endogamous divisions of the Pan- chalas differ in clifferent localities. In the Carnatic they appear to have four sub-divisions, Panchanan, Patkari, Vidur and Shilwant, the last beinfe formed of those who are converted to Lingayitism. Vidurs are the illegitimate offspring of Panchal fathers and mothers of other castes. Patkaris allow their widows to remarry and consequently form a separate group. In Te'jngana the caste is divided into four sub-castes bearing the nan\es Panchdayis, Baiti Panchdayis, Balja Panchdayis, and Chontikulam,,of which the first represent the original stock. Baiti Panchalas are said to have been sprung from illicit con- nections between the members of the Panchal caste, while the Chonti- kulam are the progeny of Pemchala men and women of Munnur, Mutrasi and other lower castes. Balija Panchalas are proselytes to Lingayitism, wear both the sacred thread (the emblem of Brahmins) and the Lingam and acknowledge Jangams as their priests. Besides these there are two other classes, who are mendicants and beg only from the cast4. Pansas are said to be descended from Komatis who" lost their caste, having had to eat the leavings of Panchadayis, as ' they could not pay their debts and were forced to undergo this humiliation. Unjawaru are alleged to derive their name from 'Unja,' their professional musical instru- ment, so named after a demon who was killed by Vishwakarma while in the act of playing upon the instrument. The main divi- sions of the Maratha Panchals are identical with the occupational groups comprised in their names, viz.. Sonar, Sutar, Lohar, Tambatkar (kasar), and Goundi. Some of them are further sub- divided into smaller divisions, which are also endogamous. Thus Sonars are divided into Konkani, Daivadnya and Rathkar; Sutars into Panchal and Lingade, the latter being the illegitimate descendants of the former sub-caste; Tambatkars into Konkani Kasars and Tambatgars. These several classes do not intermarry.

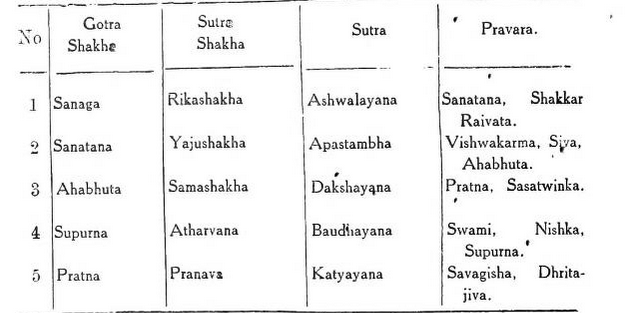

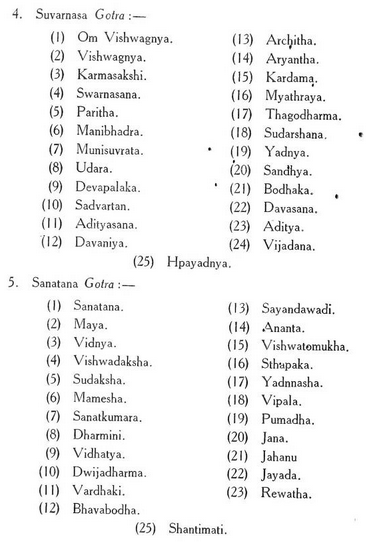

The exogamous system of the Panchals is of the eponymous type and consists of five Brahminical gotras, each branched into twenty- five divisions, making up a total of 125 sections. The prmcipal gotras, with Shakhas and Pravars pertaining to each, are illustrated m

These Brahminical gotras are recognised only in theory and few, save a very limited section of the so-called Vishwa Brahma Shastris and bhikshukas, practise them. Intermarriages are really regulated by a number of exogamous sections, mostly of the territorial or totemistic type. A few of these are of the tutelar character.

Exogamy is regularly practised and supplemented * by a table of prohibited degrees corresponding to that current among other castes of the locality.

Marriage

The Panchals marry their girls between the ages of five and eleven and social reproach attaches to the parents if they allow their daughters to outgrow the age of puberty before marriage. Consummation is tolerated even before the girl is physically mature. After she has attained puberty the 'garbhadan' ceremony (purification of the womb) is celebrated at her husband's house, when the pair, dressed in new clothes, are seated side by side and presented with betel-leaves, areca-nuts, almonds and cocoa-nuts, and auspicious lights are waved about their faces. They are then taken round to make obeisance before the gods and elderly members of the household. Polygamy is permitted, but a second wife is taken only when the first wife is barren or incurably diseased.

The maniage ceremony is supposed to be in the Brahma form, refened to by Manu. The preliminary negotiations for a maniage are opened by the parents of the boy and, after the selection of the girl is approved of on consultation of the horoscopes of the couple, the day is fixed for the celebration of the wedding. The upper classes employ priests from their own community while the lower ones, who are not within the reach of this innovation, still cling to their old methods, depending upon Brahmins for the per- formance of the ceremony. The ceremony begins with the invo- cation of their tutelary deity Kalika, to whom wheaten cakes and vegetables are offered and in* who3e honour the priests are feasted. Wedding booths, consisting generally of thirteen pillars, are erected at the houses of the bride ahd the bridegroom separately and to the central pillar of 'gullar' is tied an earthen pot smeared all over with lines of Kunkum (aniline) and lime and containing cotton seeds. The mouth of the vessel is encircled with kankanam (cotton thread) and covered with a burning lamp maintained throughout the ceremony. Another lamp, also burning throughout, is placed near the family gods. A few days before the wedding the bride and bridegroom are besmeared, in their own houses, with turmeric paste and oil, bathed with warm water by married women whose husbands are living and thread bracelets are fastened on their wrists. Early next morning the bridegroom with his party starts on horseback to the bride's village where, on arrival, they are temporarily accommodated at the Hanuman's temple. The bride's party, including her parents, meet them and accord a ceremonial welcome to the bridegroom, upon which a grand procession is arranged which conducts the bride- groom with music and singing to the bride's house. Under the booth the couple, both dressed in silk and adorned with paper 'Bashingams', are made to stand facing each other. The "Antarpat is held between them and they are wedded by the family priest chanting benedictory verses and sprinkling 'Akshata,' or turmeric coloured rice, over them at the end of each verse. It is customary among some Panchalas to make the couple sit in bamboo baskets when the 'Antarpat' is held between them. The rituals that follow are Jiraguda, Kankanbandhanam and Kanyadan, which" correspond in every detail to those of other high castes. The boy is investe(J with the sacred thread and required to make offerings to 'Homa,' or the sacrificial fire kindled on the earthen platform built for the purpose, 'Saptapadi,' or the seven steps, form the essential portion of the ritual. After this, the Mangalsutra (lucky necklace) is tied about the bride's neck by the family priest and the bridal pair, with their clothes knotted, worship the family gods, have a drink of milk and curds and are taken round to make obeisance before the elderly members of the family. The day's proceedings terminate with an entertainment to the caste people. The next day the wedded fair go in procession to the Hanuman's teiliple and after worshipping the god return home. At the entrance to the house* two leaf-plates containing rice and curd, coloured yello'w with turmeric powder, are waved about their faces and thrown away to the evil spirits. A 'Homa' is performed and a feast is given to the caste. On the 3rd day after wedding the 'Bhuma' rite takes place. A basket containing puris' (wheat cakes) and flour balls is covered with a winnowing fan on which a lamp of dough, smeared with lines of kunkum (aniline powder) is kept burning. The basket is placed near the god's shrine and worshipped by the parents of the bride and the bride- groom. It is then removed to the marriage booth. A puri is taken out of the basket with the point of a sword and thrown on the top of the booth, the ceremony being observed by none but the members of the household, for it is generally believed that outsiders, beholding it, bring on them the loss of their children and other calamities. A curious rite is performed at the Hanuman's temple on the 3rd day after wedding. Twenty-five small heaps of rice are arranged in front of the god and the bride, with her forehead, collects them in one mass; the bridegroom, all the while throwing on her head grains of rice one by one. 'Barat' or the return procession, on the 4th day, concludes the marriage. When the bridegroom returns with the bride to his house he is obstructed at the entrance door by his sister who demands his daughter in marriage to her son and on extracting the promise from him she allows him to enter the house with his young wife. The marriage booth is removed on the llth day after the wedding and the 'muhurta medha' (wedding post) is removed on the 21st day, the pit in which it was planted being filled with earth mixed with jaggery.

Widow-Marriage

Widows are not allowed to marry again. nor is divorce permitted. It is said that some of the Panchals prac- tise widow-marriage, but these are turned out of their caste.

Religion

The favourite object of worship of the Panchals is the goddess Kahka, also called Ambika, to whom sheep, goats, fowls and wine are offered on the first day of the bright half of Chait and again in the month of Shravana (August-September). No prifsts are employed for the worship of the goddess and the offerings are eaten by the members of ihe household. Fridays and Tuesdays are believed to ibe the mist propitious days for this worship. Offer- ings of sweetmeats are also made to the goddess Kamakshi of Kanchi, who is held to be one of their patron deities. Most of the Panchals are Shakti worshippers, but a few are either Vibhutidharis or Shai- vaits and Tirmanidharis, or Vishnu-worshippers. A number of them have adopted the tenets of Lingayitism and wear both the Lingam and the sacred thread on their person. Devotion is also paid to Rama, Dattatraya, Hanuman, Ganpati and the Sun, whose worship is conducted in the orthodox fashion. Besides these they revere the animistic deities Pochamma, Mari Amma, Nagamma, the deified saint Manik' Prabhu of Humanabad and a host of evil spirits and malignant divinities. Special respect is paid to the implements of their craft, the higher classes of the Panchals, especially members of the priesthood among them, observe all the sixteen sacraments of Brahmins and conduct their whole ceremonial according to the Vedic rites. These, like Brahmins, invest their sons with the sacred thread when 8 yecirs old.

Disposal of the Dead

The dead are disposed of by burnmg, except in the case of boys who are not invested with the sacred thread and girls who are unmanied. If the body be that of an adult man it is bathed and clothed in silk and smeared with sandal paste. In the case of a married woman whose husband is livmg it is covered with a silken sari. The corpse is borne to the cremation ground on a bamboo bier by four men and the chief mourner, with moustaches shaved, leads the way with an earthen pot, containing fire, in his hand. The dead body is placed on the funeral pile with the head to the south and the chief mourner walks five times round the pile and sets fire to it. Ashes and bones are col- lected on the third day after death and the ashes are thrown into a sacred river, while the bones are buried and over them a platform is built as a monument to the deceased. 'Sradha' is performed on the 11th and 12th days after death and on the 14th a feast is given to the caste people of the neighbourhood. Libations of water and balls of rice are offered on the occasion. Ancestors in general are propitiated in the last fifteen days of Bhadrapad. »

Social Status

Except those who maintain a high standard of ceremonial purity, the Panchals eat the flesh of |;oats, sheep and fowl and drink spirituous liquors. Their* social standing is, no doubt, highly respectable, although none of the Hindu castes, not even the lowest ones, eat food from their hands, nor do the members of the caiste eat kachi even from the hands of Brahmins.

Occupation

The Panchals are, by occupation, artisans and work in gold, brass, iron, wood and stone. Their work in India attained a high position in early ages and has been fostered by generations of diligent mei who, from father to son, have devoted their hearts and minds thereto, completing it with taste and fitting details. In the carving of wood and the chasing of metal and filagree work they excel their brethren of other countries. Specimens of their work were purchased for the Exhibition of 1 85 1 as models of tasteful design and careful work and introduced into the Schools of Arts of Europe for imitation. It is a pity that the fine arts of India are gradually dying out for want of proper encouragement. Some of the Panchals have entered Government service .and irisen to posts of honour by their talents and diligence. They are also mem- bers of learned professions. A few of them, more particularly the gold-smiths, are landlords and wealthy merchants.

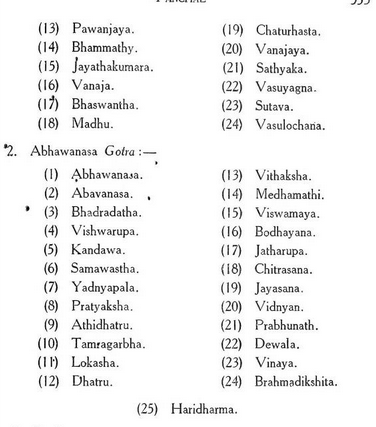

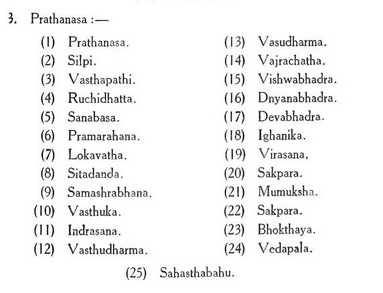

Exogamous Divisions of the Panchal Caste