Kota (South Indian tribe)

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Kota

According to Dr. Oppert “it seems probable that the Todas and Kotas lived near each other before the settlement of the latter on the Nilagiri. Their dialects betray a great resemblance. According to a tradition of theirs (the Kotas), they lived formerly on Kollimallai, a mountain in Mysore. It is wrong to connect the name of the Kotas with cow-slaying, and to derive it from the Sanskrit gō-hatyā (cow-killer). The derivation of the term Kota is, as clearly indicated, from the Gauda-dravidian word ko (ku) mountain, and the Kotas belong to the Gandian branch.” There is a tradition that the Kotas were formerly one with the Todas, with whom they tended the herds of buffaloes in common. But, on one occasion, they were found to be eating the flesh of a buffalo which had died, and the Todas drove them out as being eaters of carrion. A native report before me suggests that “it is probable that, after the migration of the Kotas to the hills, anthropology was at work, and they got into them an admixture of Toda blood.”

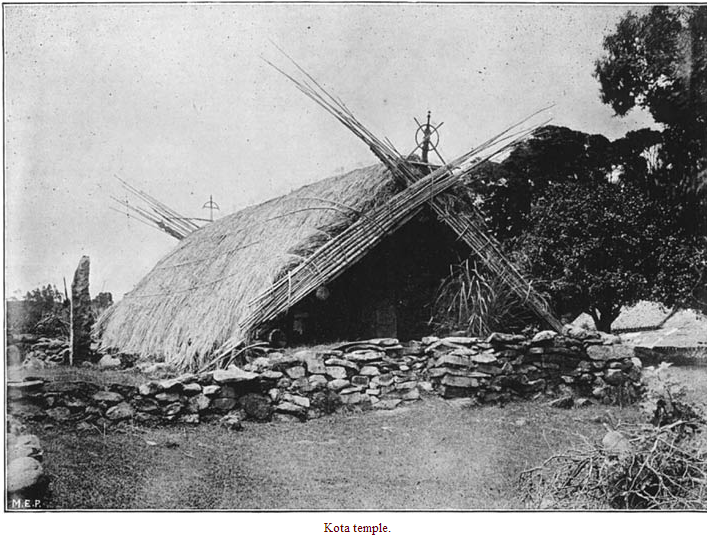

The Kotas inhabit seven villages (Kōtagiri or kōkāl), of which six—Kotagiri, Kīl Kotagiri, Todanād, Sholūr, Kethi and Kūnda—are on the Nīlgiri plateau, and one is at Gudalūr at the north-west base of these hills. They form compact communities, and, at Kotagiri, their village consists of detached huts, and rows of huts arranged in streets. The huts are built of mud, brick, or stone, roofed with thatch or tiles, and divided into living and sleeping apartments. The floor is raised above the ground, and there is a verandah in front with a seat on each side whereon the Kota loves to “take his siesta, and smoke his cheroot in the shade,” or sleep off the effects of a drinking bout. The door-posts of some of the huts are ornamented with carving executed by wood-carvers in the plains. A few of the huts, and one of the forges at Kotagiri, have stone pillars sculptured with fishes, lotuses, and floral embellishments by stone-carvers from the low country. It is noted by Breeks that Kurguli (Sholūr) is the oldest of the Kota villages, and that the Badagas believe that the Kotas of this village were made by the Todas. At Kurguli there is a temple of the same form as the Toda dairy, and this is said to be the only temple of the kind at any Kota village.

The Kotas speak a mixture of Tamil and Kanarese, and speak Tamil without the foreign accent which is noticeable in the case of the Badagas and Todas. According to orthodox Kota views, a settlement should consist of three streets or kēris, in one of which the Terkāran or Dēvādi, and in the other two the Munthakannāns or Pūjāris live. At Kotagiri the three streets are named Kīlkēri, Nadukēri, and Mēlkēri, or lower, central, and upper street. People belonging to the same kēri may not intermarry, as they are supposed to belong to the same family, and intermarriage would be distasteful. The following examples of marriage between members of different kēris are recorded in my notes:—

Husband. Wife.

Kīlkēri. Nadukēri.

Kīlkēri. Mēlkēri.

Nadukēri. Mēlkēri.

Mēlkēri. Nādukēri.

Nadukēri. First wife Kīlkēri, second wife Mēlkēri.

The Kota settlement at Shōlūr is divided into four kēris, viz.:—amrēri, kikēri, korakēri, and akkēri, or near street, lower street, other street, and that street, which resolve themselves into two exogamous groups. Of these, amrēri and kikēri constitute one group, and korakēri and akkēri the other.

On the day following my arrival at Kotagiri, a deputation of Kotas waited on me, which included a very old man bearing a certificate appointing him headman of the community in recognition of his services and good character, and a confirmed drunkard with a grog-blossom nose, who attributed the inordinate size thereof to the acrid juice of a tree, which he was felling, dropping on it. The besetting vice of the Kotas of Kotagiri is a partiality for drink, and they congregate together towards dusk in the arrack shop and beer tavern in the bazar, whence they stagger or are helped home in a state of noisy and turbulent intoxication. It has been said that the Kotas “actually court venereal disease, and a young man who has not suffered from this before he is of a certain age is looked upon as a disgrace.”

The Kotas are looked down on as being unclean feeders, and eaters of carrion; a custom which is to them no more filthy than that of eating game when it is high, or using the same tooth-brush week after week, is to a European. They have been described as a very carnivorous race, who “have a great craving for flesh, and will devour animal food of every kind without any squeamish scruples as to how the animal came by its death. The carcase of a bullock which has died of disease, or the remains of a deer half devoured by a tiger, are equally acceptable to him.” An unappetising sight, which may be witnessed on roads leading to a Kota village, is that of a Kota carrying the flesh of a dead buffalo, often in an advanced stage of putridity, slung on a stick across his shoulders, with the entrails trailing on the ground. Colonel Ross King narrates how he once saw a Kota carrying home a dead rat, thrown out of a stable a day or two previously. When I repeated this story to my Kota informant, he glared at me, and bluntly remarked in Tamil “The book tells lies.” Despite its unpleasant nature, the carrion diet evidently agrees with the Kotas, who are a sturdy set of people, flourishing, it is said, most exceedingly when the hill cattle are dying of epidemic disease, and the supply of meat is consequently abundant.

The missionary Metz narrates that “some years ago the Kotas were anxious to keep buffaloes, but the headmen of the other tribes immediately put their veto upon it, declaring that it was a great presumption on the part of such unclean creatures to wish to have anything to do with the holy occupation of milking buffaloes.” The Kotas are blacksmiths, goldsmiths, silversmiths, carpenters, tanners, rope-makers, potters, washermen, and cultivators. They are the musicians at Toda and Badaga funerals. It is noted by Dr. W. H. R. Rivers that “in addition they provide for the first Toda funeral the cloak (putkuli) in which the body is wrapped, and grain (patm or s(=a)mai) to the amount of five to ten kwa. They give one or two rupees towards the expenses, and, if they should have no grain, their contribution of money is increased. At the marvainolkedr (second funeral ceremony) their contributions are more extensive. They provide the putkuli, together with a sum of eight annas, for the decoration of the cloak by the Toda women. They give two to five rupees towards the general expenses, and provide the bow and arrow, basket (tek), knife (kafkati), and the sieve called kudshmurn. The Kotas receive at each funeral the bodies of the slaughtered buffaloes, and are also usually given food.”

Though all classes look down on the Kotas, all are agreed that they are excellent artisans, whose services as smiths, rope and umbrella makers, etc., are indispensable to the other hill tribes. The strong, durable ropes, made out of buffalo hide, are much sought after by Badagas for fastening their cattle. The Kotas at Gudalūr have the reputation of being excellent thatchers. The Todas claim that the Kotas are a class of artisans specially brought up from the plains to work for them. Each Toda, Badaga, Irula, and Kurumba settlement has its Muttu Kotas, who work for the inhabitants thereof, and supply them with sundry articles, called muttu, in return for the carcasses of buffaloes and cattle, ney (clarified butter), grain, plantain, etc. The Kotas eat the flesh of the animals which they receive, and sell the horns to Labbai (Muhammadan) merchants from the plains. Chakkiliyans (leather-workers) from the plains collect the bones, and purchase the hides, which are roughly cured by the Kotas with chunam (lime) and āvaram (Cassia auriculata) bark, and pegged out on the ground to dry.

The Kota blacksmiths make hatches, bill-hooks, knives, and other implements for the various hill tribes, especially the Badagas, and also for European planters. Within the memory of men still living, they used to work with iron ore brought up from the low country, but now depend on scrap iron, which they purchase locally in the bazar. The most flourishing smithy in the Kotagiri village is made of bricks of local manufacture, roofed with zinc sheets, and fitted with anvil pincers, etc., of European manufacture.

As agriculturists the Kotas are said to be quite on a par with the Badagas, and they raise on the land adjacent to their villages crops of potatoes, bearded wheat (akki or rice ganji), barley (beer ganji), kīrai (Amarantus), sāmai (Panicum miliare), korali (Setaria italica), mustard, onions, etc. At the revenue settlement, 1885, the Kotas were treated in the same way as the Badagas and other tribes of the Nīlgiris, except the Todas, and the lands in their occupation were assigned to them at rates varying from ten to twenty annas per acre. The bhurty or shifting system of cultivation, under which the Kotas held their lands, was formally, but nominally, abolished in 1862–64; but it was practically and finally done away with at the revenue settlement of the Nīlgiri plateau. The Kota lands are now held on puttas under the ordinary ryotwari tenure. In former days, opium of good quality was cultivated by the Badagas, from whom the Kotas got poppy-heads, which their herbalists used for medicinal purposes. At the present time, the Kotas purchase opium in the bazar, and use it as an intoxicant.

The Kota women have none of the fearlessness and friendliness of the Todas, and, on the approach of a European to their domain, bolt out of sight, like frighted rabbits in a warren, and hide within the inmost recesses of their huts. As a rule they are clad in filthily dirty clothes, all tattered and torn, and frequently not reaching as low as the knees. In addition to domestic duties, the women have to do work in the fields, fetch water and collect firewood, with loads of which, supported on the head by a pad of bracken fern (Pteris aquilina) leaves, and bill-hook slung on the shoulder, old and young women, girls and boys, may continually be seen returning to the Kotagiri village. The women also make baskets, and rude earthen pots from a black clay found in swamps on a potter’s wheel. This consists of a disc made of dry mud, with an iron spike, by means of which it is made to revolve in a socket in a stone fixed in the space in front of the houses, which also acts as a threshing-floor. The earthenware vessels used by the Todas for cooking purposes, and those used in dairy work, except those of the inner room of the ti sacred dairy), are said by Dr. Rivers to be made by the Kotas.

The Kota priesthood is represented by two classes, Munthakannān or Pūjāri, and Terkāran or Dēvādi, of whom the former rank higher than the latter. There may be more than two Terkārans in a village, but the Munthakannāns never exceed this number, and they should belong to different kēris. These representatives of the priesthood must not be widowers, and, if they lose their wives while holding office, their appointment lapses. They may eat the flesh of buffaloes, but not drink their milk. Cow’s flesh, but not its milk, is tabu. The Kotas may not milk cows, or, under ordinary conditions, drink the milk thereof in their own village, but are permitted to do so if it is given to them by a Pūjāri, or in a village other than their own. The duties of the Munthakannān include milking the cows of the village, service to the god, and participation in the seed-sowing and reaping ceremonial. They must use fire obtained by friction, and should keep a fire constantly burning in a broken pot.

In like manner, the Terkārans must not use matches, but take fire from the house of the Munthakannān. The members of the priesthood are not allowed to work for others, but may do so on their own account in the fields or at the forge. They should avoid pollution, and may not attend a Toda or Badaga funeral, or approach the seclusion hut set apart for Kota women. When a vacancy in the office of Munthakannān occurs, the Kotas of the village gather together, and seek the guidance of the Terkāran, who becomes inspired by the deity, and announces the name of the successor. The selected individual has to be fed at the expense of the community for three months, during which time he may not speak to his wife or other woman direct, but only through the medium of a boy, who acts as his assistant. Further, during this period of probation, he may not sleep on a mat or use a blanket, but must lie on the ground or on a plank, and use a dhupati (coarse cloth) as a covering. At the time of the annual temple festival, neither the Munthakannāns nor the Terkārans may live or hold communion with their wives for fear of pollution, and they have to cook their food themselves.

The seed-sowing ceremony is celebrated in the month of Kumbam (February-March) on a Tuesday or Friday. For eight days the Pūjāri abstains from meat and lives on vegetable dietary, and may not communicate directly with his wife, a boy acting as spokesman. On the Sunday before the ceremony, a number of cows are penned in a kraal, and milked by the Pūjāri. The milk is preserved, and, if the omens are favourable, is said not to turn sour. If it does, this is attributed to the Pūjāri being under pollution from some cause or other. On the day of the ceremony, the Pūjāri bathes in a stream, and proceeds, accompanied by a boy, to a field or the forest. After worshipping the gods, he makes a small seed-pan in the ground, and sows therein a small quantity of rāgi (Elusine Coracana). Meanwhile, the Kotas of the village go to the temple, and clean it. Thither the Pūjāri and the boy proceed, and the deity is worshipped with offerings of cocoanuts, betel, flowers, etc. Sometimes the Terkāran becomes inspired, and gives expression to oracular utterances. From the temple all go to the house of the Pūjāri, who gives them a small quantity of milk and food. Three months later, on an auspicious day, the reaping of the crop is commenced with a very similar form of ceremonial. During the seed-sowing festival, Mr. Harkness, writing in 1832, informs us, “offerings are made in the temples, and, on the day of the full moon, after the whole have partaken of a feast, the blacksmith and the gold and silversmith, constructing separately a forge and furnace within the temple, each makes something in the way of has avocation, the blacksmith a chopper or axe, the silversmith a ring or other kind of ornament.”

“Some rude image,” Dr. Shortt writes, “of wood or stone, a rock or tree in a secluded locality, frequently forms the Kota’s object of worship, to which sacrificial offerings are made; but the recognised place of worship in each village consists of a large square of ground, walled round with loose stones, three feet high, and containing in its centre two pent-shaped sheds of thatch, open before and behind, and on the posts (of stone) that support them some rude circles and other figures are drawn. No image of any sort is visible here.” These sheds, which at Kotagiri are a very short distance apart, are dedicated to Siva and his consort Parvati under the names of Kāmatarāya and Kālikai.

Though no representation thereof is exhibited in the temples at ordinary times, their spirits are believed to pervade the buildings, and at the annual ceremony they are represented by two thin plates of silver, which are attached to the upright posts of the temples. The stones surrounding the temples at Kotagiri are scratched with various quaint devices, and lines for the games of kotē and hulikotē. The Kotas go, I was told, to the temple once a month, at full moon, and worship the gods. Their belief is that Kāmatarāya created the Kotas, Todas, and Kurumbas, but not the Irulas. “Tradition says of Kāmatarāya that, perspiring profusely, he wiped from his forehead three drops of perspiration, and out of them formed the three most ancient of the hill tribes—the Todas, Kurumbas, and Kotas. The Todas were told to live principally upon milk, the Kurumbas were permitted to eat the flesh of buffalo calves, and the Kotas were allowed perfect liberty in the choice of food, being informed that they might eat carrion if they could get nothing better.” According to another version of this legend given by Dr. Rivers, Kāmatarāya “gave to each people a pot. In the Toda pot was calf-flesh, and so the Todas eat the flesh of calves at the erkumptthpimi ceremony; the Kurumba pot contained the flesh of a male buffalo, so this is eaten by the Kurumbas. The pot of the Kotas contained the flesh of a cow-buffalo, which may, therefore, be eaten by this people.”

.”In addition to Kāmatarāya and Mangkāli, the Kotas at Gūdalūr, which is near the Malabar frontier, worship Vettakaraswāmi, Adiral and Udiral, and observe the Malabar Ōnam festival. The Kotas worship further Māgāli, to whose influence outbreaks of cholera are attributed, and Māriamma, who is held responsible for smallpox. When cholera breaks out among the Kota community, special sacrifices are performed with a view to propitiating the wrath of the goddess. Māgāli is represented by an upright stone in a rude temple at a little distance from Kotagiri, where an annual ceremony takes place, at which some man becomes possessed, and announces to the people that Māgāli has come. The Pūjāri offers up plantains and cocoanuts, and sacrifices a sheep and fowls. My informant was, or pretended to be ignorant of the following legend recorded by Breeks as to the origin of the worship of the smallpox goddess. “A virulent disease carried off a number of Kotas of Peranganoda, and the village was abandoned by the survivors. A Badaga named Munda Jogi, who was bringing his tools to the Kotagiri to be sharpened, saw near a tree something in the form of a tiger, which spoke to him, and told him to summon the run-away Kotas. He obeyed, whereupon the tiger form addressed the Kotas in an unknown tongue, and vanished. For some time, the purport of this communication remained a mystery. At last, however, a Kota came forward to interpret, and declared that the god ordered the Kotas to return to the village on pain of a recurrence of the pestilence. The command was obeyed, and a Swāmi house (shrine) was built on the spot where the form appeared to the Badaga (who doubtless felt keenly the inconvenience of having no Kotas at hand to sharpen his tools).” The Kotas are not allowed to approach Toda or Badaga temples.

It was noted by Lieutenant R. F. Burton that, in some hamlets, the Kotas have set up curiously carved stones, which they consider sacred, and attribute to them the power of curing diseases, if the member affected be only rubbed against the talisman.

A great annual festival is held in honour of Kāmatarāya with the ostensible object of propitiating him with a view to his giving the Kotas an abundant harvest and general prosperity. The feast commences on the first Monday after the January new moon, and lasts over many days, which are observed as a general holiday. The festival is said to be a continuous scene of licentiousness and debauchery, much indecent dancing taking place between men and women. According to Metz, the chief men among the Badagas must attend, otherwise their absence would be regarded as a breach of friendship and etiquette, and the Kotas would avenge themselves by refusing to make ploughs or earthen vessels for the Badagas. The programme, when the festival is carried out in full detail, is, as far as I have been able to gather, as follows:—

First day. A fire is kindled by one of the priests in the temple, and carried to the Nadukēri section of the village, where it is kept burning throughout the festival. Around the fire men, women, adolescent boys and girls, dance to the weird music of the Kota band, whose instruments consist of clarionet, drum, tambourine, brass horn and flute (buguri). Second day Dance at night.

Third day

Fourth day

Fifth day

Sixth day.

The villagers go to the jungle and collect bamboos and rattans, with which to re-roof the temple. Dance at night. The seventh day is busily spent in re-roofing and decorating the temples, and it is said to be essential that the work should be concluded before nightfall. Dance at night. Eighth day. In the morning the Kotas go to Badaga villages, and cadge for presents of grain and ghī (clarified butter), which they subsequently cook, place in front of the temple as an offering to the god, and, after the priests have eaten, partake of, seated round the temple.

Ninth day. Kotas, Todas, Badagas, Kurumbas, Irulas, and ‘Hindus’ come to the Kota village, where an elaborate nautch is performed, in which men are the principal actors, dressed up in gaudy attire consisting of skirt, petticoat, trousers, turban and scarves, and freely decorated with jewelry, which is either their own property, or borrowed from Badagas for the occasion. Women merely dressed in clean cloths also take part in a dance called kumi, which consists of a walk round to time beaten with the hands. I was present at a private performance of the male nautch, which was as dreary as such entertainments usually are, but it lacked the go which is doubtless put into it when it is performed under natural conditions away from the restraining influence of the European. The nautch is apparently repeated daily until the conclusion of the festival.

Eleventh and twelfth days. A burlesque representation of a Toda funeral is given, at which the part of the sacrificial buffaloes is played by men with buffalo horns fixed on the head, and body covered with a black cloth. At the close of the festival, the Kota priests and leading members of the community go out hunting with bows and arrows, leaving the village at 1 A.M., and returning at 3 A.M. They are said to have formerly shot ‘bison’ (Bos gaurus) at this nocturnal expedition, but what takes place at the present day is said to be unknown to the villagers, who are forbidden to leave their houses during the absence of the hunting party. On their return to the village, a fire is lighted by friction. Into the fire a piece of iron is put by one of the priests, made red hot with the assistance of the bellows, and hammered. The priests then offer up a parting prayer to the god, and the festival is at an end. The following is a translation of a description by Dr. Emil Schmidt of the dancing at the Kota annual festival, at which he had the good fortune to be present as an eye-witness:—

“During my stay at Kotagiri the Kotas were celebrating the big festival in honour of their chief god. The feast lasted over twelve days, during which homage was offered to the god every evening, and a dance performed round a fire kept burning near the temple throughout the feast. On the last evening but one, females, as well as males, took part in the dance. As darkness set in, the shrill music, which penetrated to my hotel, attracted me to the Kota village.

At the end of the street, which adjoins the back of the temple, a big fire was kept up by continually putting on large long bundles of brushwood. On one side of the fire, close to the flames, stood the musicians with their musical instruments, two hand-drums, a tambourine, beaten by blows on the back, a brass cymbal beaten with a stick, and two pipes resembling oboes. Over and over again the same monotonous tune was repeated by the two latter in quick four-eight time to the accompaniment of the other instruments. On my arrival, about forty male Kotas, young and old, were dancing round the fire, describing a semicircle, first to one side, then the other, raising the hands, bending the knees, and executing fantastic steps with the feet. The entire circle moved thus slowly forwards, one or the other from time to time giving vent to a shout that sounded like Hau! and, at the conclusion of the dance, there was a general shout all round. Around the circle, partly on the piles of stone near the temple, were seated a number of Kotas of both sexes. A number of Badagas of good position, who had been specially invited to the feast, sat round a small fire on a raised place, which abuts on the back wall of the temple. The dance over, the circle of dancers broke up.

The drummers held their instruments, rendered damp and lax by the moist evening breeze, so close to the flames that I thought they would get burnt. Soon the music began again to a new tune; first the oboes, and then, as soon as they had got into the proper swing, the other instruments. The melody was not the same as before, but its two movements were repeated without intercession or change. In this dance females, as well as males, took part, grouped in a semicircle, while the men completed the circle. The men danced boisterously and irregularly. Moving slowly forwards with the entire circle, each dancer turned right round from right to left and from left to right, so that, after every turn, they were facing the fire. The women danced with more precision and more artistically than the men. When they set out on the dance, they first bowed themselves before the fire, and then made left and right half turns with artistic regular steps.

Their countenances expressed a mixture of pleasure and embarrassment. None of the dancers wore any special costume, but the women, who were nearly all old and ugly, had, for the most part, a quantity of ornaments in the ears and nose and on the neck, arms and legs. In the third dance, played once more in four-eight times, only females took part. It was the most artistic of all, and the slow movements had evidently been well rehearsed beforehand. The various figures consisted of stepping radially to and fro, turning, stepping forwards and backwards, etc., with measured seriousness and solemn dignity. It was for the women, who, at other times, get very little enjoyment, the most important and happiest day in the whole year.”

In connection with Kota ceremonials, Dr. Rivers notes that “once a year there is a definite ceremony, in which the Todas go to the Kota village with which they are connected, taking an offering of clarified butter, and receiving in return an offering of grain from the Kotas. I only obtained an account of this ceremony as performed between the people of Kars and the Kota village of Tizgudr, and I do not know whether the details would be the same in other cases. In the Kars ceremony, the Todas go on the appointed day to the Kota village, headed by a man carrying the clarified butter. Outside the village they are met by two Kota priests whom the Todas call teupuli, who bring with them a dairy vessel of the kind the Todas call mu, which is filled with patm grain. Other Kotas follow with music. All stand outside the village, and one of the Kotas puts ten measures (kwa) of patm into the pocket of the cloak of the leading Toda, and the teupuli give the mu filled with the same grain. The teupuli then go to their temple and return, each bringing a mu, and the clarified butter brought by the Todas is divided into two equal parts, and half is poured into each mu. The leading Toda then takes some of the butter, and rubs it on the heads of the two Kota priests, who prostrate themselves, one at each foot of the Toda, and the Toda prays as follows:—

May it be well; Kotas two, may it be well; fields flourish may; rain may; buffalo milk may; disease go may. “The Todas then give the two mu containing the clarified butter to the Kota priests, and he and his companions return home. This ceremony is obviously one in which the Todas are believed to promote the prosperity of the Kotas, their crops, and their buffaloes.

“In another ceremonial relation between Todas and Kotas, the kwòdrdoni ti (sacred dairy) is especially concerned. The chief annual ceremony of the Kotas is held about January in honour of the Kota god Kambataraya. In order that this ceremony may take place, it is essential that there should be a palol (dairy man) at the kwòdrdoni ti, and at the present time it is only occupied every year shortly before and during the ceremony. The palol gives clarified butter to the Kotas, which should be made from the milk of the arsaiir, the buffaloes of the ti. Some Kotas of Kotagiri whom I interviewed claimed that these buffaloes belonged to them, and that something was done by the palol at the kwòdrdoni ti in connection with the Kambataraya ceremony, but they could not, or would not, tell me what it was.”

In making fire by friction (nejkōl), the Kotas employ three forms of apparatus:—

(1) a vertical stick, and horizontal stick with sockets and grooves, both made of twigs of Rhodomyrtus tomentosus;

(2) a small piece of the root of Salix tetrasperma is spliced into a stick, which is rotated in a socket in a piece of the root of the same tree;

(3) a small piece of the root of this tree, made tapering at each end with a knife or fragment of bottle glass, is firmly fixed in the wooden handle of a drill. A shallow cavity and groove are made in a block of the same wood, and a few crystalline particles from the ground are dropped into the cavity. The block is placed on several layers of cotton cloth, on which chips of wood, broken up small by crushing them in the palm of the hand, are piled up round the block in the vicinity of the grove. The handle is, by means of a half cocoanut shell, pressed firmly down, and twisted between the palms, or rotated by means of a cord. The incandescent particles, falling on to the chips, ignite them In a report by Lieutenant Evans, written in 1820, it is stated that “the marriages of this caste (the Kothewars) remind one of what is called bundling in Wales. The bride and bridegroom being together for the night, in the morning the bride is questioned by her relatives whether she is pleased with her husband-elect.

If she answers in the affirmative, it is a marriage; if not, the bridegroom is immediately discharged, and the lady does not suffer in reputation if she thus discards half a dozen suitors.” The recital of this account, translated into Tamil, raised a smile on the face of my Kota informant, who volunteered the following information relating to the betrothal and marriage ceremonies at the present day. Girls as a rule marry when they are from twelve to sixteen years old, between which years they reach the age of puberty. A wife is selected for a lad by his parents, subject to the consent of the girl’s parents; or, if a lad has no near relatives, the selection is made for him by the villagers. Betrothal takes place when the girl is a child (eight to ten). The boy goes, accompanied by his father and mother, to the house where the girl lives, prostrates himself at the feet of her parents, and, if he is accepted, presents his future father-in-law with a four-anna piece, which is understood to represent a larger sum, and seals the contract.

According to Breeks, the boy also makes a present of a birianhana of gold, and the betrothal ceremony is called balimeddeni (bali, bracelet, meddeni, I have made). Both betrothal and marriage ceremonies take place on Tuesday, Wednesday, or Friday, which are regarded as auspicious days. The ceremonial in connection with marriage is of a very simple nature. The bridegroom, accompanied by his relatives, attends a feast at the house of the bride, and the wedding day is fixed. On the appointed day the bridegroom pays a dowry, ranging from ten to fifty rupees, to the bride’s father, and takes the girl to his house, where the wedding guests, who have accompanied them, are feasted. The Kotas as a rule have only one wife, and polyandry is unknown among them. But polygamy is sometimes practiced. My informant, for example, had two wives, of whom the first had only presented him with a daughter, and, as he was anxious to have a son, he had taken to himself a second wife. If a woman bears no children, her husband may marry a second, or even a third wife; and, if they can get on together without fighting, all the wives may live under the same roof.

Divorce may, I was told, be obtained for incompatibility of temper, drunkenness, or immorality; and a man can get rid of his wife ‘if she is of no use to him’, i.e., if she does not feed him well, or assist him in the cultivation of his land. Divorce is decided by a panchāyat (council) of representative villagers, and judgment given, after the evidence has been taken, by an elder of the community. Cases of theft, assault, or other mild offence, are also settled by a panchāyat, and, in the event of a case arising which cannot be settled by the members of council representing a single village, delegates from all the Kota villages meet together. If then a decision cannot be arrived at, recourse is had to the district court, of which the Kotas steer clear if possible. At a big panchāyat the headman (Pittakar) of the Kotas gives the decision, referring, if necessary, to some ‘sensible member’ of the council for a second opinion.

When a married woman is known to be pregnant with her first child, her husband allows the hair on the head and face to grow long, and leaves the finger nails uncut. On the birth of the child, he is under pollution until he sees the next crescent moon, and should cook his own food and remain at home. At the time of delivery a woman is removed to a hut (a permanent structure), which is divided into two rooms called dodda (big) telullu and eda (the other) telullu, which serve as a lying-in chamber and as a retreat for women at their menstrual periods. The dodda telullu is exclusively used for confinements. Menstruating women may occupy either room, if the dodda telullu is not occupied for the former purpose. They remain in seclusion for three days, and then pass another day in the raised verandah of the house, or two days if the husband is a Pūjāri. A woman, after her first confinement, lives for three months in the dodda telullu, and, on subsequent occasions, until the appearance of the crescent moon. She is attended during her confinement and stay in the hut by an elderly Kota woman. The actual confinement takes place outside the hut, and, after the child is born, the woman is bathed, and taken inside. Her husband brings five leafy twigs of five different thorny plants, and places them separately in a row in front of the telullu. With each twig a stick of Dodonæa viscosa, set alight with fire made by friction, must be placed. The woman, carrying the baby, has to enter the hut by walking backwards between the thorny twigs.

A common name for females at Kotagiri is Mādi, one of the synonyms of the goddess Kālikai, and, at that village, the first male child is always called Komuttan (Kāmatarāya). At Shōlūr and Gudalūr this name is scrupulously avoided, as the name of the god should not be taken by mortal man. As examples of nicknames, the following may be cited. • Small mouth.

• Head.

• Slit nose.

• Burnt-legged.

• Monkey.

• Dung or rubbish.

• Deaf.

• Tobacco.

• Hunchback.

• Crooked-bodied.

• Long-striding.

• Dwarf

• Opium eater

• Irritable.

• Bad-eyed.

• Curly-haired.

• Cat-eyed.

• Left-handed.

• Stone.

• Stammerer.

• Short.

• Knee.

• Chank-blower.

• Chinaman.

The nickname Chinaman was due to the resemblance of a Kota to the Chinese, of whom a small colony has squatted on the slopes of the hills between Naduvatam and Gudalūr.

A few days after my arrival at Kotagiri, the dismal sound of mourning, to the weird strains of the Kota band, announced that death reigned in the Kota village. The dead man was a venerable carpenter, of high position in the community. Soon after daybreak, a detachment of villagers hastened to convey the tidings of the death to the Kotas of the neighbouring villages, who arrived on the scene later in the day in Indian file, men in front and women in the rear. As they drew near the place of mourning, they all, of one accord, commenced the orthodox manifestations of grief, and were met by a deputation of villagers accompanied by the band. Meanwhile a red flag, tied to the top of a bamboo pole, was hoisted as a signal of death in the village, and a party had gone off to a glade, some two miles distant, to obtain wood for the construction of the funeral car (tēru). The car, when completed, was an elaborate structure, about eighteen feet in height, made of wood and bamboo, in four tiers, each with a canopy of turkey red and yellow cloth, and an upper canopy of white cloth trimmed with red, surmounted by a black umbrella of European manufacture, decorated with red ribbands. The car was profusely adorned with red flags and long white streamers, and with young plantain trees at the base.

Tied to the car were a calabash and a bell. During the construction of the car the corpse remained within the house of the deceased man, outside which the villagers continued mourning to the dirge-like music of the band, which plays so prominent a part at the death ceremonies of both Todas and Kotas. On the completion of the car, late in the afternoon, it was deposited in front of the house. The corpse, dressed up in a coloured turban and gaudy coat, with a garland of flowers round the neck, and two rupees, a half-rupee, and sovereign gummed on to the forehead, was brought from within the house, lying face upwards on a cot, and placed beneath the lowest canopy of the car. Near the head were placed iron implements and a bag of rice, at the feet a bag of tobacco, and beneath the cot baskets of grain, rice, cakes, etc. The corpse was covered with cloths offered to it as presents, and before it those Kotas who were younger than the dead man prostrated themselves, while those who were older touched the head of the corpse and bowed to it.

Around the car the male members of the community executed a wild step-dance, keeping time with the music in the execution of various fantastic movements of the arms and legs. During the long hours of the night mourning was kept up to the almost incessant music of the band, and the early morn discovered many of the villagers in an advanced stage of intoxication. Throughout the morning, dancing round the car was continued by men, sober and inebriated, with brief intervals of rest, and a young buffalo was slaughtered as a matter of routine form, with no special ceremonial, in a pen outside the village, by blows on the back and neck administered with the keen edge of an adze. Towards midday presents of rice from the relatives of the dead man arrived on the back of a pony, which was paraded round the car. From a vessel containing rice and rice water, water was crammed into the mouths of the near relatives, some of the water poured over their heads, and the remainder offered to the corpse.

At intervals a musket, charged with gunpowder, which proved later on a dangerous weapon in the hands of an intoxicated Kota, was let off, and the bell on the car rung. About 2 P.M., the time announced for the funeral, the cot bearing the corpse, from the forehead of which the coins had been removed, was carried to a spot outside the village called the thāvāchivadam, followed by the widow and a throng of Kotas of both sexes, young and old. The cot was then set down, and, seated at some distance from it, the women continued to mourn until the funeral procession was out of sight, those who could not cry spontaneously mimicking the expression of woe by contortion of the grief muscles. The most poignant sorrow was displayed by a man in a state of extreme intoxication, who sat apart by himself, howling and sobbing, and wound up by creating considerable disturbance at the burning-ground.

Three young bulls were brought from the village, and led round the corpse. Of these, two were permitted to escape for the time being, while a vain attempt, which would have excited the derision of the expert Toda buffalo-catchers, was made by three men, hanging on to the head and tail, to steer the third bull up to the head of the corpse. The animal, however, proving refractory, it was deemed discreet to put an end to its existence by a blow on the poll with the butt-end of an adze, at some distance from the corpse, which was carried up to it, and made to salute the dead beast’s head with the right hand, in feeble imitation of the impressive Toda ceremonial. The carcase of the bull was saluted by a few of the Kota men, and subsequently carried off by Pariahs. Supported by females, the exhausted widow of the dead man was dragged up to the corpse, and, lying back beside it, had to submit to the ordeal of removal of all her jewellery, the heavy brass bangle being hammered off the wrist, supported on a wooden roller, by oft-repeated blows with mallet and chisel delivered by a village blacksmith assisted by a besotten individual noted as a consumer of twelve grains of opium daily.

The ornaments, as removed, were collected in a basket, to be worn again by the widow after several months. This revolting ceremony concluded, and a last salutation given by the widow to her dead husband, arches of bamboo were attached to the cot, which was covered over with a coloured table-cloth hiding the corpse from sight. A procession was then formed, composed of the corpse on the cot, preceded by the car and musicians, and followed by male Kotas and Badagas, Kota women carrying the baskets of grain, cakes, etc., a vessel containing fire, and burning camphor. Quickly the procession marched to the burning-ground beyond the bazar, situated in a valley by the side of a stream running through a glade in a dense undergrowth of bracken fern and trailing passion-flower.

On arrival at the selected spot, a number of agile Kotas swarmed up the sides of the car, and stripped it of its adornments including the umbrella, and a free fight for the possession of the cloths and flags ensued. The denuded car was then placed over the corpse, which, deprived of all valuable ornaments and still lying on the cot, had been meanwhile placed, amid a noisy scene of brawling, on the rapidly constructed funeral pyre. Around the car faggots of wood, supplied in lieu of wreaths by different families in the dead man’s village as a tribute of respect, were piled up, and the pyre was lighted with torches kindled at a fire which was burning on the ground close by. As soon as the pyre was in a blaze, tobacco, cigars, cloths, and grain were distributed among those present, and the funeral party dispersed, leaving a few men behind in charge of the burning corpse, and peace reigned once more in the Kota village. A few days later, the funeral of an elderly woman took place with a very similar ceremonial. But, suspended from the handle of the umbrella on the top of the car, was a rag doll, which in appearance resembled an Aunt Sally. I was told that, on the day following the funeral, the smouldering ashes are extinguished with water, and the ashes, collected together, and buried in a pit, the situation of which is marked by a heap of stones. A piece of the skull, wrapped in bracken fronds, is placed between two fragments of an earthen pot, and deposited in the crevice of a rock or in a chink in a stone wall.

The Kotas celebrate annually a second funeral ceremony in imitation of the Todas. For eight days before the day appointed for its observance, a dance takes place in front of the houses of those Kotas whose memorial rites are to be celebrated, and three days before they are performed invitations are issued to the different Kota villages. On a Sunday night, fire is lighted by friction, and the time is spent in dancing. On the following day, the relatives of the departed who have to perform the ceremony purify the open space in front of their houses with cow-dung. They bring three basketfuls of paddy (unhusked rice), which are saluted and set down on the cleansed space. The Pūjāri and the rest of the community, in like manner, salute the paddy, which is taken inside the house. On the Monday, cots corresponding in number to that of the deceased whose dry funeral is being held, are taken to the thāvachivadam, and the fragments of skulls are laid thereon. Buffaloes (one or more for each skull) are killed, and a cow is brought near the cots, and, after a piece of skull has been placed on its horns, sacrificed. A dance takes place around the cots, which are removed to the burning-ground, and set on fire. The Kotas spend the night near the thāvachivadam. On the following day a feast is held, and they return to their homes towards evening, those who have performed the ceremony breaking a small pot full of water in front of their houses.

Like the Todas, the Kotas indulge in trials of strength with heavy spherical stones, which they raise, or attempt to raise, from the ground to the shoulders, and in a game resembling tip-cat. In another game, sides are chosen, of about ten on each side. One side takes shots with a ball made of cloth at a brick propped up against a wall, near which the other side stands. Each man is allowed three shots at the brick. If it is hit and falls over, one of the ‘out-side’ picks up the ball, and throws it at the other side, who run away, and try to avoid being hit. If the ball touches one of them, the side is put out, and the other side goes in. A game, called hulikotē, which bears a resemblance to the English child’s game of fox and geese, is played on a stone chiselled with lines, which forms a rude game-board. In one form of the game, two tigers and twenty-five bulls, and in another three tigers and fifteen bulls engage, and the object is for the tigers to take, or, as the Kotas express it, kill all the bulls. In a further game, called kotē, a labyrinthiform pattern, or maze, is chiselled on a stone, to get to the centre of which is the problem. The following notes are taken from my case-book:—

Man—Blacksmith and carpenter. Silver bangle on right wrist; two silver rings on right little finger; silver ring on each first toe. Gold ear-rings. Langūti (cloth) tied to silver chain round loins. Man—Light blue eyes, inherited from his mother. His children have eyes of the same colour. Lobes of ears pendulous from heavy gold ear-rings set with pearls. Another man with light blue eyes was noticed by me. Man—Branded with cicatrix of a burn made with a burning cloth across lower end of back of forearm. This is a distinguishing mark of the Kotas, and is made on boys when they are more than eight years old. Woman—Divorced for being a confirmed opium-eater, and living with her father.

Woman—Dirty cotton cloth, with blue and red stripes, covering body and reaching below the knees. Woman—Two glass bead necklets, and bead necklet ornamented with silver rings. Four brass rings, and one steel ring on left forearm. Two massive brass bangles, weighing two pounds each, and separated by cloth ring, on right wrist. Brass bangle with brass and steel pendants, and shell bangle on left wrist. Two steel rings, and one copper ring on right ring-finger; brass rings on left first, ring, and little fingers. Two brass rings on first toe of each foot. Tattooed lines uniting eyebrows. Tattooed on outer side of both upper arms with rings, dots, and lines; rows of dots on back of right forearm; circle on back of each wrist; rows of dots on left ankle. As with the Todas, the tattooed devices are far less elaborate than those of the women in the plains.

Woman—Glass necklet ornamented with cowry shells, and charm pendant from it, consisting of a fragment of the root of some tree rolled up in a ball of cloth. She put it on when her baby was quite young, to protect it against devils. The baby had a similar charm round its neck.

In the course of his investigation of the Todas, Dr. Rivers found that of 320 males 41 or 12.8 per cent. and of 183 females only two or 1.1 per cent. were typical examples of red-green colour-blindness. The percentage in the males is quite remarkable. The result of examination of Badaga and Kota males by myself with Holmgren’s wools was that red-green colour-blindness was found to be present in 6 out of 246 Badagas, or 2•5 per cent. and there was no suspicion of such colour-blindness in 121 Kotas.