Oraon, Uraon Kunokh, Kunrukh

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Contents |

Oraon, Uraon Kunokh, Kunrukh

Tradition of Origin

A Dravidian cultivating tribe of Chota Nagpur, classed on linguistic grounds as Dravidian and suppose to be closely askin to the Males of the Hajmabal hills. Their tradition say that their original home was in the west of India, whence they came to the Kaimur hills and the plateau of Rohtas in Shahabad. Driven from Rohtas by the Muhamadans, the tribe split into two divisions. One of these, under the Chief, followed the course of the Ganges, and finally settled in the Rajmahal hills; while the other, led by his younger brother, went up the Son into Palamau, and turning eastward along the Koel took possession of the north-western portion of the chota Nagpur plateau. Some say that they expelled the Mundas from this portion of the country, and forced them to retire to their present settlements in the south of Lohardaga; but this statement is not borne out by local tradition, nor can it be reconciled with the fact that the few Mundas found in the Oraon pa?'ganas on the plateau are acknowledged and looked up to as the descendants of the founders of the villages in which they live.

Physical characterstic

The colour of most Oraons is the darkest brown, approaching to black; the hair being jet black, coarse, and rather inclined to be frizzy. projecting Jaws and teeth, thick lips, low narrow foreheads, broad flat noses, are the features which strike a careful observer as characteristic of the tribe. The eyes are often bright and full, and no obliquity is observable in the opening of the eyelids. No signs of Mongolian affinities can be detected in the relative positions of the nasal and malar bones, and the average naso-malar index for a hundred Oraons measured on the system recommended by Mr. Oldfield Thomas comes to 113'6.

Dress and ornaments

"The dress of the men," says Colonel Dalton, "consists of a long narrow strip of cloth carefully adjusted as a middle garment, but in such a manner as to leave the wearer most perfect freedom of limb, and allow the full play of the muscles of the thigh and hip to be seen. They wear nothing in the form of a coat; the decorated neck and chest are undraped, displaying how the latter tapers to the waist, which the young dandies compress within the smallest compass. In addition to the cloth, there is always round the waist a girdle of cords made of tasa1' silk or of cane. This is now a superfluity, but it is no doubt the remnant of a more primitive costume, perhaps the support of the antique fig leaves. Alter the age of ornamentation is passed, nothing can be more untidy or unprepossessing than the appearance of the Oraon. The ornaments are nearly all discarded, hair utterly neglect¬ed, and for raiment any rags are used. This applies both to males and females of middle age. The ordinary dress of the women depends somewhat on the degree of civilization, and on the part of the country in which you make YOUT observations. In the villages about Lohardaga, a cloth from the waist to a little below the knee is the common working dress; but where there is more association with other races, the persons of young females are decently clad in the coarse cotton cloth of the country, white with red border. Made-up garments are not worn except by the converts to Christianity. The one cloth, six yards long, is gracefully adjusted so as to form a shawl and a petti¬coat. The Oraons do not, as a rule, bring the upper end of the garment over the head, and so give it the functions also of a veil, as it is worn by the Bengali women; they simply throw the end of the dress over the left shoulder, and it falls with its fringe and ornamented border prettily over the back of the figure. Vast quantities of red beads and a large heavy brass ornament, shaped like a torque, are worn round the neck. On the left hand are rings of copper, as many as can be indued on each finger up to the first joint; on the right hand a smaller quantity. Rings on the second toe only, of brass or bell¬metal, and anklets and bracelets of the same material are also worn. The hair is, as a rule, coarse and rather inclined to be frizzy, but by dint of lubrication they can make it tolerably smooth and amenable; and raIse hair or some other substance is used to give size to the mass (the chignon) into which it is gathered, not immediately behind, but more or less on one side, so that it lies on the neck just behind, and touching the right ear; and flowers are arranged in a receptable made for them between the roll of hair and the head. The ears are, as usual with suoh people, terribly mutilated for decorative purposes ; spikes and rings are inserted into holes made in the upper cartilage, and the lobe is widely distended. When in full danoing costume, they add to their head-dress plumes of heron feathers, and a gay bordered soarf is tightly bound round the upper part of the body."

Bachelor’s dormitory

In matters of domestic economy the Oraons are a slovenly race, and their badly-built mud huts afford no Bachelor's dormitory. sufficient accommodation for the unmarried members of the family. In the older Oraon villages this difficulty is provided for by a house called the dhumkuria, in which all the baohelors must sleep under penalty of a fine. Where the girls sleep is, says Colonel Dalton, "somewhat of a mystery':' In some villages a separate building, under the charge of an elderly woman, is maintained for their use; and more commonly they are distributed among the widows of the village. " But however billeted, it is well known that they often find their way to the baohelors' hall, and in some villages actually sleep there." This curious institution is not peculiar to the Oraons. We meet with it among the Juangs, the Hill Bhuiyas of Keonjhur and Bonai, and the Jhumia Maghs of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The Onion system, though already looked upon as an ancient custom, and apparently tending to disuse in newly-formed villages, is still very elaborate. "The Dhumkuria fraternity are under the severest penalties bound down to secrecy in regard to all that takes place in their dormitory; and even girls are punished if they dare to tell tales. They are not allowed to join in the dances till the offence is condoned. They have a regular system of fagging in this curious institution. The small boys serve those of larger growth, shampoo their limbs, and comb their hair, etc., and they are sometimes subjected to severe discipline to make men of them." It is difficult not to see in this a survival of more primitive modes of life, possibly even of the initiatory ceremonies to which many tribes of savages attach so much importance.

Internal structure

'The internal structure of the Off the Orans tribe is shown in a tabular form in Appendix 1. The exogamous septs are extremely numerous, and all that can be identified are totemistic, the totem being taboo to the members of the sept. The rule of exogamy in force is the simple one that a man may not marry a woman of his own sept. The sept name descends in the male line, and there is no objection to a man marrying a woman belonging to the same sept as hi mother. In addition to this some system of prohibited degrees seems to exist among them, though no one can state it clearly, nor is it expressed in a definite formula. Still every Oraon will admit that he cannot marry his maternal aunt or his first cousin on the mother's side, though he will probably not be able to say how far these prohibitions go in the descending line. So also no one can marry his younger brother's widow or the elder sister of his deceased wife, though marriage with an elder brother's widow or a deceased wife's younger sister is deemed permissible.

Marriage

Seventeen years ago, when Colonel Dalton published hi account of the Oraons, infant-marriage is said to have

been entirely unknown among the tribe. A few of the wealthier men, who affect to imitate Hindu customs, have now taken to this practice, and marry thell' daughters before they have attained puberty. Among the mass of to-e people, however, girls marry after they are grown up, and the freest courtship prevails at dances, festivals, and social gatherings of various kinds, Young men woo their sweethearts with offerings of flowers for the hair and presents of grilled field-mice, " which the Oraons declare to be the most delicate of food." Sexual intercourse before marriage is tacitly recognized, and is so generally practised that in the opinion of the best observers on 01'<1.on girl is a virgin at the time of her marriage. To call this state of things immoral is to apply a modern conception to prUnitive habits of life. Within the tribe indeed the idea of sexual morality seems hardly to exist, and the unmarried Oraons are not far removed from the condition of modi¬fied promiscuity which prevails among many of the Australian tribes. Provided that the exogamous circle defined by the totem is respected, an unmarried woman may bestow her favours on whom she will. 1£, however, she becomes pregnant, arrangements are made to get her married without delay, and she is then expected to lead a virtuous life. Prostitution is unknown. Intrigues beyond the limits of the tribe are uncommon, and are punished by summary expulsion. Colonel Dalton gives the following account of the Oraon marriage system :¬ " When a young man makes up his mind to marry, his parents or guardians go through a form of selection for him; but it is always a girl that he has already selected for himself, and between whom and hUn there is a perfect understanding. The parents, however, have to arrange all preliminarie , including the price of the damsel, which is sometimes as low as Rs. 4 (s.) In the vi its that are intel'¬ changed by the negotiators, omens are rorefully observed by the On10ns, as by the Mundas, and there are, consequently, similar difficulties to overcome; but when all is settled, the bridegroom proceeds with a large party of his friends, male and female, to' the bride's house. Most of the males have warlike weapons, real or sham, and as they approaoh the village of the bride's family the young men from thence emerge, also armed, as if to repel the inva ion, and a mimio fight ensues, whioh, like a dissolving view, blends pleasantly into a dance. In this the bride and bridegroom join, each riding on the hips of one of their friends . A bower is oonstructed in front of the residence of the bride's father, into which the bride and bridegroom are carried by women, and made to stand on a curry-stone, under which is plaoed a sheaf of corn, resting on a plough yoke. Here the mystery of the sindiu'dan is performed; but the operation is carefully screened from view, first by cloths thrown over the young couple, secondly by a cirole of their male friends, some of whom bold up a screen cloth, while others keep guard with weapons upraised and look very fierce, as if they had been told off to cut down intruders, and were quite prepared to do so. In Ora on marriages the bridegroom stands on the curry-stone behind the bride, but in order that this may not be deemed a concession to the female, his toes are so placed as to tread on her heels.

The old women under the cloth are very particular about this, as if they were specially interested in providing that the heel of the woman should be properly bruised. Thus poised the man stretches over the girl's head and daubs her forehead and crown with the red powder sindill'; and if the girl is allowed to return the compliment (it is a controverted point whether she should do so or not), she performs the ceremony without turning her head, reaching back over her own shoulder and just touching his brow. When this is accomplished, a gun is fired; and then, by some arrangement, vessels full of water, placed over the bower, are capsized, and the young couple and those who stand near them receive a drenching shower-bath. They now retire into an apartment prepared for them, ostensibly to change their clothes, but they do not emerge for some time, and when they appear they are saluted as man and wife. Dancing is kept up during their retirement, one of the performers executing a pas seuZ with a basket on her head, which is said to contain the trousseau. The OdlOns have no prescribed wedding garments, They do not follow the Hindu oustom of using saffrcn¬coloured robes on such occasions. The bride is attired in ordinary habiliments, and no special pains are taken to make her lovely for the occasion. The bridegroom is better dressed than usual. He wears a long ooat and a tUl'ban. N or have the Oraons any special days or seasons for marriages. The ceremony may take place in any month of the year, but, with all natives, the hot, dry months are generally selected if possible. There is then not much work on hand; granaries are full, and they prefer those months for marching and camping out."

Polygamy is permitted, and in theory at least there is no limit to the number of wives a man may have. This luxury, however, is but little sought after. Onions are usually too poor to maintain many wives, and the majority content themselves with one. Widows may marry again, and are subject to no restrictions in selecting their second husbands. In such marriages the full ceremony is not performed: it is deemed sufficient for the female relatives of the bridegroom to smear vermilion on the bride's forehead and the parting of her hair. Sometimes even this meagre form is omitted, and a valid marriage is constituted by the mere fact of the parties living together. Notwithstanding this laxity of formal observance, the children of a widow are recognized as holding equal rank with those of a woman married by the full ritual used in a first marriage. Divorce is readily effected at the will of either husband or wife.

The consent of the panchayat is not required, nor is the intention to separate attested by any particular form. A husband turns away his wife, or a wife runs off from her husband, and the fact in either case is accepted as constituting a valid divorce. If a woman has children, her husband may be compelled to contribute to their maintenance if he divorces the mother on any other ground than adultery. Similarly, when a wife deserts her husband, not on account of ill-treatment, but merely because she takes a fancy to another man, her parents may be called upon to repay the bride-price which they received at her marriage. Divorced wives may marry again on the same terms and by the same form as widows.

ReligIOn

"The religion of the Onions," says Colonel Dalton, "is of a composite order. They have, no doubt, retained some portion of the belief that they broul2"ht with them to Chota Nagpur; but, coalescing with the Mundas and joining in their festivals and acts of public worship, they have to a certain extent adopted their ideas on religion and blended them with their own. There is, however, a material distinction between the religious systems of the two people. The Mundas have no symbols and make no representations of their gods; the Oraons, and all the cognates whom I have met with, have always some visible object of worship, though it may be but a stone or a wooden post, or a lump of earth. Like the Mundas, they acknowledge a Supreme God, adored as Dharmi or Dharmesh, the Holy One, who is manifest in the sun; and they regard Dharmesh as a perfectly pure, beneficent being, who created us, and would in his goodness and mercy preserve us, but that his benevolent designs are thwarted by malignant spirits whom mortals must propitiate, as Dharmesh oannot or does not interfere if the spirit of evil once fastens upon us. It is therefore of no use to pray to Dharmesh or to offer sacrifices to him; so though acknowledged, recognized, and reverenced, he is neglected, whilst the malignant spirits are adored. "I do not think that the Oraons have an idea that their sins are visited on them, either in this world or in a world to Gome. It is not because they are wicked that their children or their cattle die, or their crops fail, or they suffer in body; it is only because some malignant demon has a spite against them, or is desirous of harming them. Their ideas of sin are limited. Thou shalt not commit adultery, thou shalt not steal, thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour, is about as much of the Decalogue as they would sub¬scribe to. It is doubtful if they see any moral guilt in murder, though hundreds of them have suffered the ex~reme penalty of the law for this crime. They are ready to take life on very slight provo¬cation, and in the gratification of their revenge an innocent child is as likely to suffer as the actual offender. There is one canon of the Mosaicallaw that thbY in former years rigorously enforced¬'Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.' I have dwelt on this sub¬ject in treating of the Mundas. If left to themselves, the life of elderly females would be very insecure. As it is, a suspected old woman (and sometimes a young one, especially if she be the daughter of a suspected old one) is occasionally condemned, well drubbed and turned out of the village; and she does not always survive the treat¬ment she is subjected to. If we analyse the views of most of the Oraon converts to Christianity, we shall, I think, be able to discern the influence of their pagan doctrines and superstitions in the motives that first led them to become catechumens. The Supreme Being who does not proteot them from the spite of malevolent spirits has, they are assured, the Christians under His special care. They consider that, in consequence of this guardianship, the witohes and bhuts have no power over Christians; and it is, therefore, good for them to join that body. They are taught that for the salvation of Christians one great sacrifice has been made, and they see that those who are baptized do not in faot reduce their live-stock to pro¬pitiate the evil spirits. They grasp at this notion; and long after¬wards, when they understand it better, the atonement, the mystioal washing away of sin by the blood of Christ, is the doctrine on which their simple minds most dwell. I have not found amongst the pagan Oraons a trace of the high moral code that their cousins of the H.ajmaMl hills are said to have accepted. I consider that they have no belief whatever in a future state, whilst to the RajmahaHs is attri¬buted a profound system of metempsychosis. The Oraons carry that doctrine no further than to suppose that men who are killed by tigers becoms tigers, but for other people death means annihilation. As the sole object of their religious ceremonies is the propitiation of the demons, who are ever thwarting the benevolent intentions of Dharmesh, they have no notion of a service of thanks¬giving; and so far we may regard the l'eligion of the Mundas as of a higher order than theirs. When suffering or misfortune befall a man, he consults an augw:, or oilui, as to the cause of his afllic-tion, and acts according to the advice given. The ojlui has it in his power to denounce a mortal or a partioular devil. The method employed has been desoribed in the account of tho Mundas, and the result is the same. If a fellow-being is denounced, it is said that he has caused his familiar to possess and aflliot the sufferer; and the person denounced is seized and tortured, or beaten, to force himto effect the expulsion of the evil spirit. But the family or village bMt may be accused. The ojlui, under inspiration, of course, deoides what is to be sacrificed, and :frequently ruins, if he does not cure, the patient consulting him. In the process of propitiation, the fetish natUl'e of the Oraon belief is shown. '1'he sorcerer produces a mall image of mud, and on it sprinkles a few grains of rice. If fowls are to be the victims, they are placed in front of this image; and if they peck at the rice, it iudicates that the particular devil is satisfied with the intention of his votaries, and the sacrifice proceeds. The flesh of the animals killed is appropriated by the sorcerer, so it is his interest to have a hecatomb if possible. In regard to the names and attri¬butes of the devils, the Oraon s who live with Mundas sacrifice to Marang Buru and all the Munda Bongas. The Oraons on the western portion of the plateau, where there are few Mundas, ignore the Bongas and pay their devotion to Darha, the Sarna Burhi (Lady of the Grove), and the village Mitts, who have various names. Chanda or Chandt is the god or goddess of the ohase, and is always invoked preparatory to starting on great hunting expeditions. Any bit of rock, or stone, or exoresoenoe on a rook, serves to represent this deity. The hill near Lodhma, known to the Mundas as MarangBuru, is held in great reverenoe by the Oraons. To the spirit of the hill, whom they oall Baranda, they give bullocks and buffaloes, espe-oially propitiating him as the Mid, who, when malignantly inclined, frustrates God's designs of sending rain in due season to fertilise the earth. In some parts of the oountry Darha is almost the only spirit they propitiate. If fowls are offered to him, they must be of divers colours, but once in three years he should have a sheep from his votaries; and onoe in the same period a buffalo, of which the oJM or pahn gets a quarter. The Oraon must always have something material to worship, renewed every three years. Besides this superstitious dread of the spirits above namen, the Orion's imagin¬ation tremblingly wanders in a world of ghosts. Every rock, road, river, and grove is haunted. He believes that women who die in childbirth become ghosts, oalled c/tol"ail; and suoh ghosts are fre-quently met hovering about the tombstones, always clad in robes of white, their faoes fair and lovely, but with baoks black as charcoal, and inverted feet, that is, they walk with their heels in front. 'l'hey lay hold of passers-by and wrestle with them, and tickle them; and he is lucky, indeed, who, thus oaught, escapes without permanent injuries." Women who die within fifteen days of their confiuement are believed to be likely to beoome c/~01'ails; but thi danger may be averted by offeriug sacrifices for the repose of their spirits.

Festivals

The Oraons do not employ Brahmans, and their religious and ceremonial ob ervances are supervised by priests of their own tribe known as N aiyas. "The Oraons and Mundas keep the same festivals; but, accord¬ ing to Mr. Luther, the Karm is, with the former, the most important. It is celebrated at the season for planting out the rice grown in seed-beds, and is observed by Hindus as well as by Kols and other tribes. On the first day of the feast the villagers must not break their fast till certain ceremonies have been performed. In the evening a party of young people of both sexes proceed to the forest, and cnt a young km'ma tree (Nauc/ea parvijotia); or the branch of one, bearing which they return in triumph,-dancing, and singing, and beating drums,-and plant it in the middle of the dkhra. After the performance of a sacrifioe to the Karma Deota by the pdlm, the k villagers feast, and the night is passed iu danoing and revelry. Next morning all Day be seen at an early hour in holiday array; the elders in groups, under the fine old tamarind trees that surround the akMn, and the youth of both sexes, arm-linked in a huge cil'cle, dancing round the karma tree, which, festooned with garlands, decorated with strips of coloured cloth, sham bracelets and necklets of plaited straw, and with the bright faces and merry laughter of the young people encircling it, reminds one of the gift-bearing tree so often introduced at our own Christmas festival, and suggests the probability of some remote connection between the two. Pre¬paratory to the festival, the daughters of the headmen of the village cultivate blades of barley ill a peculiar mauner. The seed is sown in moist, sandy soil, mixed with a quantity of turmeric, and the blades sprout and unfold of a pale yellow or primrose colour. On the kcwma day, these blades are taken up by the roots, as if for transplantmg, and carried in baskets by the fair cultivaLors to the aklwa. 1'hey approach the karma tree, and, prostrating themselves reverentially, place before it some of the plants. They then go round the company, and, like bridesmaids distributing wedding favours, present to each person a few of the yellow barley blades, and all soon appear, wearing, ~enerally in their hair, thIS diEtinctive decoration of the festival. Then all join merrily in the karma dances, and malignant indeed must be the Mid who is not propitiated by so attractive a gathering. The morning revel closes with the removal of the karma. It is taken away by the merry throng and thrown into a stream or tank; but after another feast dancing and drinking are resumed. On the following morning the effects of the two nights' dissipation are oIten, I fear, very palpable." Colonel Dalton notices that the karma festival is celebrated by Hindus as well as by the aboriginal tribes, and quotes a passage from the Bhavishya Purana, the object of which appears to be to explain how a festival of an aboriginal people came to be adopted by the Hindus. He also points out that the necessity of the females of the family joining in the ceremony is an argument against its Hindu origin. "The On1.ons have some observances during the Sarhtil festival that differ a little from those of the Mundas. Their idea is that at this season the marriage of Dharti, the earth, is celebrated; and this cannot be done till the sal trees give the flowers for the ceremony. It takes place, then, towards the end of March or beginning of April; but any day whilst the sal trees are in blo som will answer. On the day fixed the villagers accompany their pizlm to the sarna, the sacred grove, a remnant of the old sat forest, in which the Oraons locate a popular deity, called the Sarna Bw:hi, or woman of the grove, corresponding with the Jahir Era and Desauli of the Mundas. To this dryad, who is supposed to have great influence on the rain (a superstition not unlikely to have been founded on the importance of trees as cloud-compellers), the pahn, arriving with his party at the grove, offers five fowls. These are afterwards cooked with rice, and a small quantity of the food is given to each person present. They then collect a quantity of sal flowers and return laden with them to the village. Next day the pahn, with some of the males of the village, pays a visit to every house, carrying the flowers in a wide, open basket. The females of each house take out water to wash his feet as he approaches, and, kneeling before him, make a most respectful obeisance. He then dances with them, and places over the door of the house, and in the hair of the women, some of the sat flowers. The moment that this is accomplished, they throw the contents of their water-vessels over his venerable person, heartily dousing the man whom a moment before they were treating with such profound respect. But to prevent his catchiu~ cold they ply him with as much of the home-brew as ~e can drink, consequently his reverence is generally gloriously drunk 'before he completes his round. The feasting and beer-drinking now become general; and after the meal the youth of both sexes, decked with sat flowers (they make an exceedingly becom¬ing head-dress), flock to the aMra, and dance all night and best part of next day."

Disposal of the dead

"Where a death occurs in an OrftOn family, it is made known by the lamentations of the women, who loosen their hair (a demonstration 0 grief wmch appears to prevail in all countries) and cry vigorously. They lay out the body on the common cot, called clui,TfJ(Li; and, after washing it carefully, convey it to the appointed burning-place, covered with a new cloth, and escorted by all the villagers, male and female, who are able to attend. In some families the funeral procession proceeds with music, but others dislike this custom, and nothing is heard but the cries of the women. When they have arrived at the place where the funeral pile has been prepared, the body is again washed, and the nearest relations of the deceased make offerings of rice, and put rice into the mouth of the corpse, while others put pice or other coin. The body is then placed on the pile and anointed; further offerings of rice are made, and the pile is ignited by a father or mother, a wife or husband. When the body has been consumed, notice is given in the village, and there is another collection of fl'iends and relatives to collect the charred bones which remain. These are placed in a new earthen vessel, and ceremoniously taken to the village; and as the procession returns, parched rice is dropped on the road to mark the route selected. The cinerary urn is suspended to a post erected in front of the residence of the deceased; the guests are feasted, and the party then breaks up. In the month of December or January next ensuing, the friends and relations are all again collected to witness the disposal of the bones in the place that, from the first establishment of the community, has been appropriated to the purpose. 'jlhis is a point on which the Od,ons are exceedingly tenacious; and even when one of them dies far from his home, his relations will, if possible, sooner or later, recover the fragments of his bones, and bear them back to the village, to be deposited with the ashes of his ancestors. The burial ground is always near a river, stream, or tank. As the procession proceeds with music to this place, offerings of rice are continually thrown over the cinerary urn till it is deposited in the grave prepared

for it, and a large flat stone placed above. Then all must bathe, and after paying the musicians the party returns to the village. The money that was placed in the mouth of the corpse and afterwards saved from the ashes is the fee of the musicians. The person who carried the bones to the grave has to undergo purification by incense and the sprinkling of water. It is to be observed that this ceremony occurs in each village but once in the year; and on the flppointed day the ashes of all who have died duriug the year are simultaneously relegated to their final resting place. No marriage can take place in a village whilst the bones of the dead are retained there. 'l'he most ardent lovers must patiently await the day of hadbari or sepulture. The marriage season commences shortly afterwards."

Social status

In the eyes of the average Hindu the Oraons have no social status at all, and are deemed to be entirely outside the regular caste system. In the important matter of diet the main body of the tribe have as yet made no concessions to Hindu prejudice. Beef, pork, fowls, all kinds of fish, alligators, lizards, field-rats, the larVal of bees and wasps, and even the flesh of animals which have died a natural death, are reckoned lawful food. Oraons, in fact, will eat almost anything, and are looked down upon as promiscuous feeders by the Bagdis, Bauris, and other dwellers upon the outskirts of Hinduism. A common charge is that they eat snakes and jackals, but this is only partially true, for the flesh of these animals is used solely for certain obscure medicinal purposes, and is Dot recognized as a regular article of diet. It is a singular fact that the Oraons hold the ass to be sacred, and will not kill it or eat its flesh, thus assigning to the animal much the same position and dignity as the Hindus give to the cow. No reason can be given by the members of the tribe for delighting to honour an animal which is in no way characteristic of heir present habitat; nor do I find any evidence to support the obvious conjecture that the ass may have been a tribal totem. The question of such totems and it bearing upon the problem of the origin of exogamy has been discus ed at length in the Introduction to the first volume.

Occupation

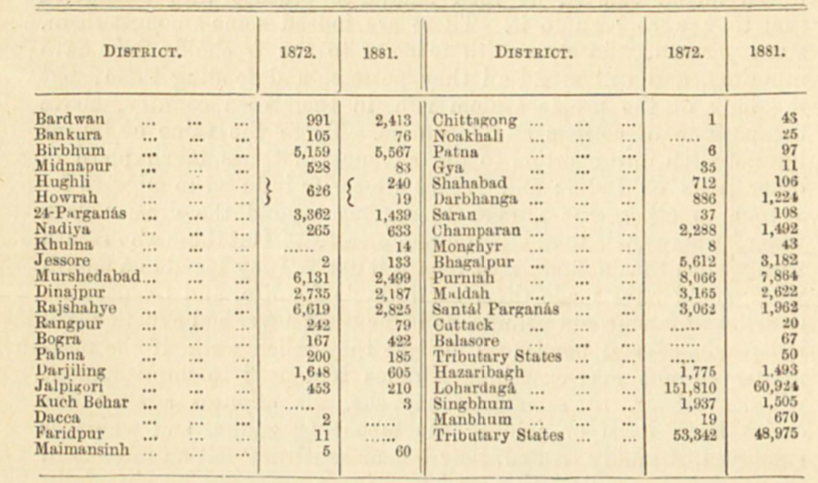

The Oraons claim to have introduced plough cultivation into Chota Nagpur, and thus to have displaced the barbarous driltri method of tillage which is carried on by burning the jungle and sowing a crop of pulse or Indian-corn in the ashes. They were certainly among the earliest settlers on the plateau of Chota Nagpur, and many of them even now hold Muin/uh'i tenures in right of being the first clearers of the soil. These rights, however, are now fast passing out of their hands, and the modern competition for land tends rather to reduce t hem to the position of tenants-at-will or landless agricultural labourers. "Their lot," says Uolonel Dalton, " is not a happy one. Not one of their own people now occupies a position which would give him the power to protect, or the influence to elevate, them from the state of degradation into which a majority of the tribe have long fallpn. They submit to be told that they were especially created as a labouring class. They have had this so often dinned into their ears, that they believe and admit it; and I have known instances of their abstaining-from claiming', as authorised by law, commutation for the forced labour exacted by their landlords, because they oonsidered that they were born to it. There are indeed some amongst them, stern yeomen, who cling with tenacity to the freeholds they have inherited, and will spend all they possess in defending them; but the bulk of the people seldom rise, in their own country, above the position of cottiers and labourers. There the value of labour has not risen in proportion to the advance that has taken place in other parts of India; and Oraons are easily induoed to migrate for a time to other climes, even to regions beyond the great 'black water.' where their work is better remunerated. But those who return with ~vealth thus aocumulated regard it not. They spend in a month what would have made them comfortable for life, and relapse into their lot of labour and penury, as if the.y had never had experienoe of independence and plenty. I believe they relish work, if the task¬master be not over-exaoting. Onions sentenced to imprisonment without labour, as sometimes happens, for offences against the excise laws, insist on joining the labouring gangs, and wherever employed, if kindly treated, they labour as if they felt an interest in the work. In cold weather or hot, rain or sun, they go cheerfully about it; and after some nine or ten hours of toil, they return blithely horne, in flower•decked groups, holding each other by the hand or round the waist, and singing. "The constitution of the OrftOn village is the same as that of the MundarL In each the hereditary tln'tnda or headman and the hereditary pa/m or priest have their lands on privileged terms, as the desoendants of the founders of the village. The hereditary estates of the two families are called ldllints, and there is sometimes a third /d)'unt, called the ma/znto; on all of these a very low rent is fixed, but there are conditions of service attached. These may now be commuted to cash payments at the instanoe of either party. There is also, under charge of the pa/m, the land dedicated to the ser-vice of the village gods. The priestly office does not always descend from fatber to SOD. The latter may be ignorant and disqualified, or he may be a Christian; therefore, when vacated, it is filled by divination. The magic sup, or winnowing-sieve, properly spelled like a divining.rod, conducts the person holding it to the door of the man most fitted to hold the office. A priest there must be; an Ora on community cannot get on without one. The fate of the village is in his hands; in their own phraseology, it is said that' he makes its affairs.' He is also master of the revels which /1re for the most part conneoted with religious rites. The dootrine of the Oraons is that man best pleases the gods when he makes merry himself; so that acts of worship and propitiatory saorifices are always associated with feasting, drinking, danoing, and love-making. The mlmda or mahato is the functionary to whom the proprietor¬of the village looks for its secular administration. In contradis¬tinotion to the palm who makes (banata) the affairs, the mahato administers (chalata) them; and he may be removed if he fail to give satisfaction." The following statement shows the number and distribution of Oraons in 1872 and 181)1 :¬