Mrinalini Sarabhai

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A dancer with a white parasol

The Hindu, January 22, 2016

Ranjana Dave

Mrinalini was more inclined to performing, and was reluctant to teach. However, she realised in her new city that if she wanted more people to dance, she would have to train them. This laid the foundation for the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts

When dancers look back at their lives, they often remark that they were born to dance. Mrinalini Sarabhai took that conviction a step further. At a young age, she already knew she was a dancer, as opposed to wanting to become one. Her life was a celebration of this belief.

Family

Though primarily identified as a dancer, Mrinalini brought to her work an acute social and political consciousness, uncommon for the times she lived in. This awareness was home-grown — her mother, Ammu Swaminathan, was a freedom fighter and later a member of India’s first Parliament. Her sister, Lakshmi Sahgal, was part of the Indian National Army.

Early life

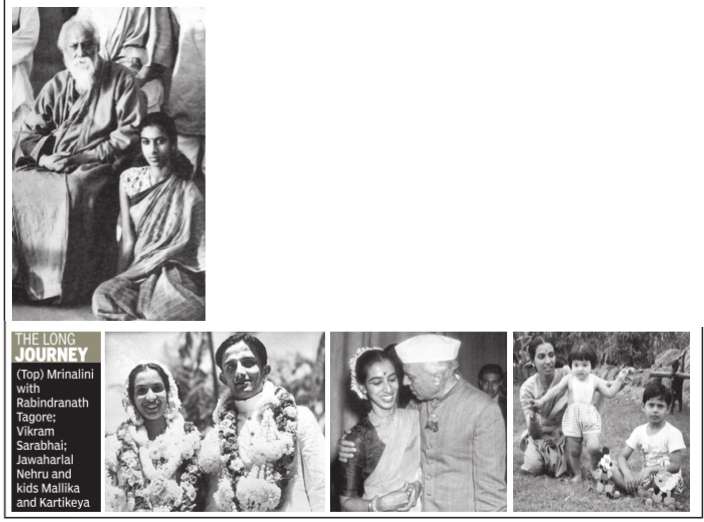

Sarabhai was born in Kerala, spending her early years in Switzerland. In school, she was introduced to Dalcroze Eurhythmics, a system of introducing musical concepts through movement. She spent time studying acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. On returning to India, she enrolled at Santiniketan where she was profoundly influenced by Rabindranath Tagore and singled him out as her only real guru.

Like many other dancers of her generation, Sarabhai trained in multiple dance styles. She learned Manipuri with Amubi Singh and Kathakali with Kunju Kurup. She also caught the attention of dancer Ram Gopal, who went on to cast her in some of his productions. Further, she studied Bharatanatyam with Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai and Muthukumar Pillai.

She met the celebrated scientist Vikram Sarabhai, who is known as the architect of India’s space programme, in Bangalore. They got married in 1942 and moved to his home in Ahmedabad. There, Mrinalini had to counter the notion that being a performer was not an acceptable career choice for “respectable women”.

Living in the post-Independence India, there was much to rejoice about. Yet, Mrinalini was also disturbed by the inequality she saw around her. Very early on, she brought social issues into her choreographic practice. “I was looking for subjects that would shake people in dance,” she once said in a documentary.

For instance, Memory is a Ragged Fragment of Eternity (1960s) was triggered by the high suicide rate of women in India. It starts with an exuberant dance by three women celebrating their womanhood and their existence. It then segues into the story of one woman, taking us on a journey through her life. It masterfully eludes the literal in its depiction of the censure that drives this woman to the brink of suicide.

Dancing in a diagonal coming downstage, two dancers use the sharp lines of a simple Bharatanatyam adavu (step) to express their suspicion and resentment towards her. Thrown at the protagonist, the mudras (gestures) have the potency of poisoned arrows. The costume reinforces the message, bringing the piece closer home. While the vocabulary is drawn from Bharatanatyam, the dancers are clad in colourful textiles from Gujarat, wearing chunky silver instead of the detailed temple jewellery of Tamil Nadu.

A biographical sketch

The Times of India, Jan 22 2016

A Padma Bhushan recipient, she was fondly referred to as `Amma'. She breathed her last at 10.10am on Thursday at her Ahmedabad home nestled inside the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts which she founded in 1949. She died of old age-related complications. In a befitting send-off, her daughter Mallika and granddaughter Anahita performed a classical dance rendition on the Darpana stage where her mortal remains were laid for people to pay their last respects. Mrinalini was born in Chennai on May 11, 1918, to a prominent family of freedom fighters. Ammu Swaminadhan, her mother, was a known Gandhian and her father an illustrious lawyer. Her sister Capt. Lakshmi Sehgal, who had joined Subhash Chandra Bose's Indian National Army (INA), died in 2012. Mrinalini belonged to Vadakath Tharavad family that has its roots in Anakkara village in Palakkad district of Kerala. After schooling in Switzerland, she went to Santiniketan as a pupil of Rabindranath Tagore and Nandlal Bose, where she received education in music and painting.

Mrinalini began her training in Bharatnatyam at a very early age. She became a favourite pupil of the great master Sri Meennakshi Sundaram Pillai of Pandanallull 1945. In an interview to TOI in 1999, she said, “I knew I would be a dancer when I was four years old. I started seeing everything in images. While listening to music at age four, I would create my own movement.“ She would add, “Dance is the breath of my life and the stage is my mother. I was born with a desperate consuming desire to create and the need to question.“ She moved to Ahmedabad after she mar ried Vikram Sarabhai, the father of Indian space programme, in 1942. She met him for the first time in Bangalore through re nowned Bharatnatyam dancer Ram Gopal, who was known to Sarabhai. “Papa said my mother broke the negative aura around Bharatnatyam at a time when women who danced were known as devdasis,“ Mallika told TOI in an earlier interview.

Mrinalini is credited with popularising choreographic forms of Bharatnatyam and Kathakali on the international stage with performances in over 100 countries. Scores of foreigners still throng to Darpana every year to learn dance. In fact, there is a school in Tokyo by the name Darpana.

In 1960-61, for the first time in the his tory of Indian classical dance, Mrinalini started conveying through her dances con temporary social issues like women empow erment, dowry deaths, Dalit rights, environ mental degradation, corruption and degradation of human values.

“When nobody knew about the word `dowry death,' she highlighted the issue in 1963 through her play after which the government published a white paper where the word was used for the first time,“ says Mallika.

“Coming to Gujarat from a very different culture might have been a kind of adventure for her and she took all in her stride,“ said son Kartikeya, leading environmentalist who represented India at COP 21 in Paris recent ly. He mentioned that she also was associ ated with initiatives such as Friends of Tree.

Mrinalini often blogged about how dance was her breath, her life. Till the last days of her life, she would oversee the affairs at Dar pana and remain present in almost all pro ductions staged at the academy . In fact, her last performance was in Kadak Badshahi, a hit production celebrating the spirit of Ahmedabad in January 2015. She had over a dozen of masterpieces to her credit, includ ing a choreography based on Beethoven's “The creatures of Prometheus“ in Italy where she worked with ballet dancing leg ends Milorad Miskovitch and Carla Fracci.

Achievements

Padma Shri: 1965

Padma Bhushan: 1992

Darpana Academy of Performing Arts

Mrinalini was more inclined to performing, and was reluctant to teach. However, she realised in her new city that if she wanted more people to dance, she would have to train them. This laid the foundation for the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, which was set up in 1948. It went on to grow into a centre for progressive arts in Ahmedabad, training thousands of students in dance, drama, music and puppetry over 68 years. Documentaries on Mrinalini’s life show her walking into Darpana, her back erect, with a pristine white parasol in her hand. She was at the centre of its rich, chaotic activity. Even in her later years, she actively taught, mentored and created new work for her students.

Mrinalini’s dance legacy is now in its third generation. She is survived by her daughter, Mallika, a dancer and political activist. Her grandson Revanta is an emerging choreographer, with roots in classical and contemporary dance forms, while her granddaughter Anahita pursues various interests in dance and choreography.

“Middle-class” women who, sheltered by the relative safety of marriage, created careers in classical dance, are both admired for the institutions they created and criticised for the conventional choices they made. Mrinalini Sarabhai is one of them. What matters most is not the institutions she gave birth to, or the dancers she trained. It is the image that she passed on to her students — that of the woman with a white parasol who danced every day, as long as she could, because she loved it.

A well wisher of humanity

The Hindu, January 28, 2016

Anjana Rajan

Mrinalini Sarabhai was a rare spirit who bridged cultures and traditions.

One does not need to be religious to realise that life on this earth is impermanent. The support that the world’s various religions offer, however, is an assurance that there is life after life, and therefore the intense turmoil, the activity and effort involved in mortal existence is not merely an offering into a great void. But even if we were to reject the theories of the soul’s journey as ‘opiates’, we cannot deny that the contributions made by people during their lifetime outlast them. The more abstract the contribution, the greater its longevity, it would seem, as is seen with the often intangible impact of artists.

Looking at the unusual life of Mrinalini Sarabhai, born in 1918, one is struck by the holistic nature of her education and accomplishments. She was a woman who, by her own admission, lived and breathed dance, but she loved beauty in its every aspect, be it in terms of nature and gardens or architecture and décor, or textiles and clothes. Trained in Bharatanatyam and Kathakali, she authored books on technique and theory of classical dance, including “Understanding Bharatanatyam” and others at a time when such books were a rarity. Besides these, she wrote on textiles as well as works of fiction. Perhaps best known as a performer, her underlying concern was for the wellbeing of humanity. The motive behind her path-breaking choreographic experiments, as she noted in her autobiography, “The Voice of the Heart” (Harper-Collins with The India Today Group, 2004), was to give expression to her own anxiety regarding the path society was taking. “Any problem dramatically shown on stage touches the heart,” she explained once, during a lecture in New Delhi on the invitation of the cultural organisation Natya Vriksha in 2007. Not surprisingly, she was possibly the first Bharatanatyam dancer to choreograph a work on deaths of young women due to dowry-related crimes. She also created pieces commenting on war and violence, taking mythology as a base but altering the ending or the emphasis of the story to put her point across — an approach worthy of note in today’s reactionary climate. In her artistic endeavours, in her education and the scope of her work, one sees two ends of a spectrum — attention to detail and a wide vision unencumbered by conventional boundaries. Schooled in Chennai and in Clarens-Montreux (Switzerland), she found her heart’s peace in Tagore’s Santiniketan at a time when she was resisting a family tradition that expected her to complete her higher studies at Oxford or Cambridge. Hers was an education that essentially continued all her life, as she travelled the world, first with her family and later with her troupe as a performing artist. It was an education imbibed too, from association with remarkable personalities: her sister Dr Lakshmi who led a battalion under Subhas Chandra Bose; family friends and caring elders who included stalwarts like Sarojini Naidu, Mahatma Gandhi, J. Krishnamurthi, Margaret Cousins and many others that pepper the history books of India and other countries. Constantly absorbing aesthetic, cultural and educational influences from her environment, the daughter of Ammu and Subbarama Swaminadhan of Kerala, Mrinalini married Vikram Sarabhai in 1942. Her marriage took her across India to Ahmedabad. Here, parallel to her own career, her husband’s eminence as one of India’s leading scientists rose, while she added to her interests the arts and crafts of Gujarat. If you were a kurta wearer in the early ‘80s, you might remember how kurtas with embroidered yokes from Gurjari, the handicrafts emporium of the Gujarat government, were all the rage. It is no irony that this trend was kicked off by the Malayali Mrinalini, then chairperson of the Handicrafts Division and one of Gurjari’s guiding forces. As a disciple of Rabindranath Tagore, she was a pan-Indian soul. An incurable romantic, perhaps, but an inspiring example nonetheless, for all those who choose to sidestep the highway of harsh commercialism and meander the paths that lead inwards to a greater freedom. The 20th Century has seen countries like India change in particularly dramatic fashion. One small example is in the relationship of the guru and disciple. Up until the 1970s and ’80s, reverence for the guru frequently meant a blinkered rejection of any other artist’s worth. In today’s internet-technology linked world, such a mindset is obsolete. But back in the late ’70s, for a devoted disciple of Rukmini Devi Arundale to say, “Mrinalini Amma is a great lady, like our Athai (Rukmini Devi),” was conceding undeniable greatness.

‘Expressing eternal truths through dance’

The Times of India, Jan 23 2016

To me, dance, apart from its essential beauty , has to be awareness and a relevant force in contemporary life. Can an artist truly exist without self-expression? It was not to meet the current desires of the audience that i began to create new works, but an innate need to express my involvement with the world around me, the world i lived in, breathed in, the world of constant dualities, joy-sorrow, life-death, love-hate, construction-destruction, creating insights towards awareness. Behind each movement was an inner energy , the result of years of training. It took hundreds of performances and relentless work to establish a reputation of classicism. Only then did i present my own perspectives.

Choreography (a word i learnt much later) is a comprehensive wholeness of a work. In dance the body speaks with the power of the mind behind it. In our country, words and music are important in the great oral tradition, but often silence seemed to me more meaningful, a totality of universal sound. But each new dance composition springs from the result of years of practice. Practice is the `puja' of a dancer, constant daily `puja'.

Dance education is more than the technique of the Natya Shastra or any other sacred text. It should envelop other perceptions if it is to become meaningful. Our puranas tell us of the valuable beauty of nature. To watch a falling leaf, the movement of water, a flight of birds, the shape of the clouds, all these are meditations that are revelatory .

`Sarva shrishti parinamam' (all creation is limitless), is a basic tenet of Indian philosophy . A dancer has to be an observer of all movement(s) as does a scientist. Vikram's remark that “it is necessary in creative work to be able to see the squirrels and the birds“ is a profound statement. It means to awaken the relationship with nature, the spirit of our Vedic heritage which tells us that we are each a particle of the universe and share in its wholeness. These thoughts of a universal oneness lead us to realise the values of our traditions when India was a land of tolerance, welcoming and protecting everyone. New ideas flowed in and were absorbed in all the arts. But underlying every art are the eternal truths as told to us by Devi, Shiva, Krishna and the great seers.

In this century of material progress, it is imperative that universal oneness is taught from the earliest age. The child has to learn to look inwards as well as outwards, the inner and the outer sky , to be observant of the environment in its beauty and also ugliness, a conscious caring citizen of the world. Often a simple story in dance or drama can inspire people. Many were the dance pieces on subjects that disturbed me and often in the villages we used the popular Bhavai.