Disaster management: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

India’s preparedness

India Today May 11, 2015

Jyoti Malhotra

Nepal tragedy is possibly a precursor to even more catastrophic earthquakes in India

In the first heart-stopping minutes that followed the 7.9-magnitude earthquake that ripped through Nepal on April 25, several believers threw up their hands-both in honour and in despair-in front of the Himalayan republic's reigning deity, Lord Pashupatinath. But slowly, as the snow settles back on the Khumbu Icefall and the Indian tectonic plate resumes its ancient rhythm of subducting beneath the overriding Eurasian plate and the climbing death toll gives way to deep grief as well as deep anger. "I cannot imagine the catastrophe if an earthquake of magnitude 6 hits Delhi," says Harsh K. Gupta, president of the International Union of Geodesy & Geophysics, pointing out that the Indian capital is located in Zone 4 (the country is divided into five seismic zones). He adds, "The vast slums and unauthorised colonies, especially around the soft Yamuna floodplain, in which lakhs of people live, will be flattened like a house of cards. The Qutab Minar can probably survive an earthquake of the magnitude of 7.0, but beyond that I don't think so."

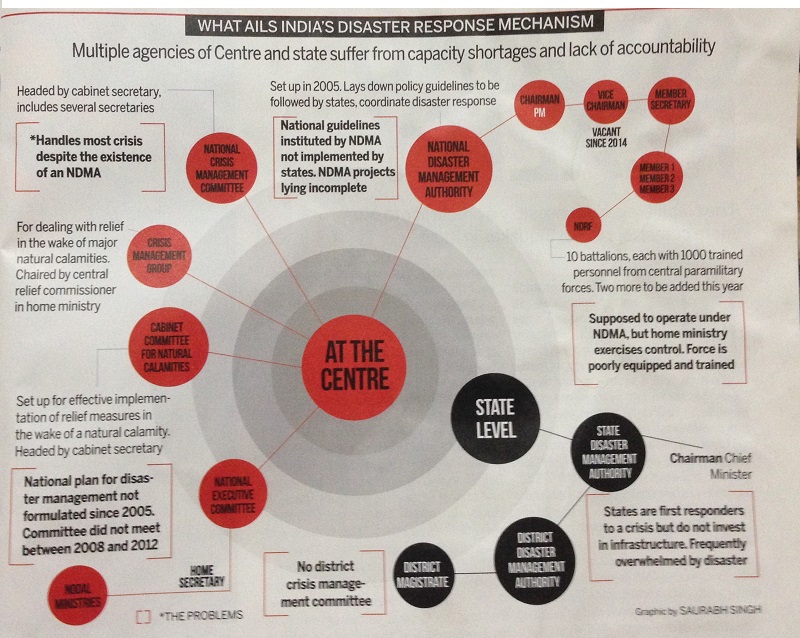

Vineet Gahalaut, seismologist at the Hyderabad-based National Geophysical Research Institute, emits a strangled laugh. "Have you seen the balconies in the houses in Old Delhi that almost touch each other as housewives exchange kitchen recipes? If a Nepal-type earthquake hits Delhi, the streets are so narrow, you won't even be able to do search and rescue," he says. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA)-set up by a government fiat in the wake of the 2001 Gujarat earthquake and the tsunami of 2004-conducted three mega drills in north India and the North-east from 2012-2014 in an effort to develop a contemporary intensity map as well as inform and educate people about the ravages of earthquakes.

Hypothetically simulating, in Chandigarh on February 13, 2013-in the middle of the night when most people are asleep-the 8.0 magnitude of the 1905 Kangra earthquake in which 20,000 people are believed to have been killed, across Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Chandigarh, the NDMA found that 1 million people would have died at present. The scenario-building exercise was repeated in 2014 across all eight states of the North-east, this time simulating the 1897 Assam earthquake of 8.7 magnitude in which around 1,500 people were killed. The NDMA found that if the earthquake had struck at night in 2014, at least 800,000 people would have died.

NDMA member Lt-Gen N.C. Marwah says the three mega drills (the first took place in Delhi in 2012, see box) created a great sense of awareness among the population, but admits that the national disaster management plan is still awaiting approval from the Prime Minister's Office. Asked about the vulnerability assessments of Delhi, or other towns falling in the highest-risk zones 4 and 5, Marwah says the NDMA doesn't have the authority to carry out any of these studies, as it is the states that must implement them. "We can only issue guidelines on how to make India disaster-resilient, and yes, the NDMA is a toothless tiger", he adds. Rohit Jigyasu, head of the risk preparedness committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, believes the NDMA guidelines need to be simpler and allow greater use of indigenous technology and construction techniques, for instance in Kashmir, where buildings are commonly constructed from wood.

"The NDMA has no guidelines for cultural heritage. For example, there are absolutely no risk management plans for Qutab Minar, which will unlikely survive a Nepal-magnitude quake," Jigyasu says. "In fact, NDMA and cultural organisations such as the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) have no contact at all. In case of a disaster, who does the ASI call?"

The NDMA passes the buck to the state governments, but no state has a comprehensive disaster management plan, says Ravi Sinha of IIT-Bombay, who helped write a risk report for Mumbai. The National Institute of Disaster Management restricts itself to policy planning and general awareness-type exercises, while the India Meteorological Division's micro-zoning of Delhi and the Ministry of Earth Sciences' (MoES) ongoing micro-zoning exercises of 30 cities is limited to topographical surveys. The incredible truth is that not one of these agencies has any information about the state of preparedness in any part of the country, both rural and urban.

And so it took a passionate professor from the department of earthquake engineering at IIT-Roorkee to blow the lid off the bureaucratic stranglehold at the MoES, which in September 2014 stopped funding a 10-year-long IIT project gathering data on structural responses to earthquakes from 293 strong ground motion instruments placed at key positions along the Himalayas.

Exactly a month before the Nepal quake, on March 26, Ashok Kumar of IIT-Roorkee wrote to MoES,complaining that the ministry had unilaterally shut down the sensor project because it wanted to give it to the ministry-controlled National Centre for Seismology.

Thakur added, presciently, "Our country will cut a very sorry face if a big earthquake event occurs, as in the present stage of instrumentation we may not get any strong motion record."

So as scientists all over the country logged in after the quake to look at data, they found there was none. IIT-Roorkee had been told to shut down its project but the new ministry-controlled seismology centre had not taken over yet.

Defending his ministry's decision, MoES Secretary Shailesh Naik told India Today that the IIT project had gone on for 10 years and it was high time it was integrated into a permanent network. "They (IIT Roorkee) should have given me a status report when the project came to an end," Naik said. "I am not a lawyer that I should check whether integration was done before or after." Naik said he was sure that at least "one or two" stations would have still recorded the Nepal earthquake "as their battery life is one year." He has now ordered a team to be sent to all stations to find out. In any case, he added, data from all 64 seismometers in the Himalayas (there are 82 all over the country) had already been released.

Meanwhile in Shimla, where bureaucratic apathy has combined with political greed to destroy a city once known as the Queen of the hills, a 2013 disaster management plan reveals that 98 per cent of the city will either collapse or suffer substantial damage if an earthquake of 7.5 magnitude occurs. According to NDMA consultant B.K. Khanna, at least 25 per cent of Shimla's population of more than 8 lakh will be killed.

"The National Building Code is a very good one and is constantly being revised," says architect-planner AGK Menon, "but it is not mandatory. The truth is that 90 per cent of buildings in any city are built without permission."

Experts rue the fact that India is totally unprepared. "We are building more high-rises on steep inclines even in the Himalayas," says M.L. Sharma, HoD, Earthquake Engineering, IIT-Roorkee. Seismologist Gahalaut says, "Indians believe that earthquakes happen to other people."

Certainly, the lack of resources accounts for a large part of India's lack of preparedness. California's advanced ShakeAlert system gave survivors a grace period of 5-10 seconds when the 2014 Napa Valley earthquake struck. Japan's early warning systems (see box) meant that the P-waves from the 9 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Sendai in 2011 gave Japan Railways about 12-22 seconds allowing the bullet trains, the Shinkansen, to grind to a halt. About 800 seismometers are operated by the Japan Meteorological Agency, while 3,600 seismic intensity meters are operated by local governments. All this information is fed into the Earthquake Phenomena Observation System in Tokyo and Osaka in real-time and disseminated. In contrast, India has placed 72 GPS instruments and 64 seismometers in the Himalayan belt.

The 7.7-magnitude earthquake on January 26, 2001 flattened Bhuj town in Gujarat. The quake left nearly 20,000 people dead.

The most earthquake-prone city in India is Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram which falls in Zone 5, with Sikkim's Gangtok a close second. A GeoHazards study notes how Aizawl clings to the hillside, some of its houses 10 storeys high. "If an earthquake comes to Aizawl," says GeoHazards' South Asia representative Hari Kumar, "just the landslides will bury thousands."

The story of apathy compounded by bureaucratic indifference and political passivity is chillingly common across the national landscape. An engineer with the Delhi Development Authority recounted how, in 2005, the state government undertook a pilot project of retrofitting five key buildings in collaboration with the American donor agency USAID to make them earthquake-proof. These included the Delhi Secretariat in which the CM's office is located, the police headquarters, the GTB hospital and Ludlow Castle school.

Some admirable work was performed-the school received a seismic belt, while the Delhi Secretariat received a full dose of seismic planning. Around 2007, after a few engineers had even been to the US for training, the work abruptly stopped. Turned out the 2010 Commonwealth Games were finally awarded to Delhi, and work had to be completed on a war footing. Delhi went to sleep until the Nepal earthquake, when Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal announced the city needed to get its act together.

And so the wheel of life continues to turn, god willing, even as the Indian tectonic plate in the Himalayas underthrusts beneath its Eurasian counterpart, each day confirming that the arrival of the Next Big One is a day closer. But if the rising death toll from the Nepal quake has one lesson for India it is that the country must finally shed its indifference that often passes off as fatalism and relearn the value of every life. Otherwise, there could be a far stiffer price to pay for that cynical shoulder shrug.

Earthquakes in India: Geo-tectonic aspect

May 11, 2015

Damayanti Datta

Hiroshima was magnitude 6.32 and Nepal 7.9. So Nepal was a thousand times more powerful. Nepal lurched closer to India by 4 metres. By the way, parts of India too slid 4 metres under Nepal.

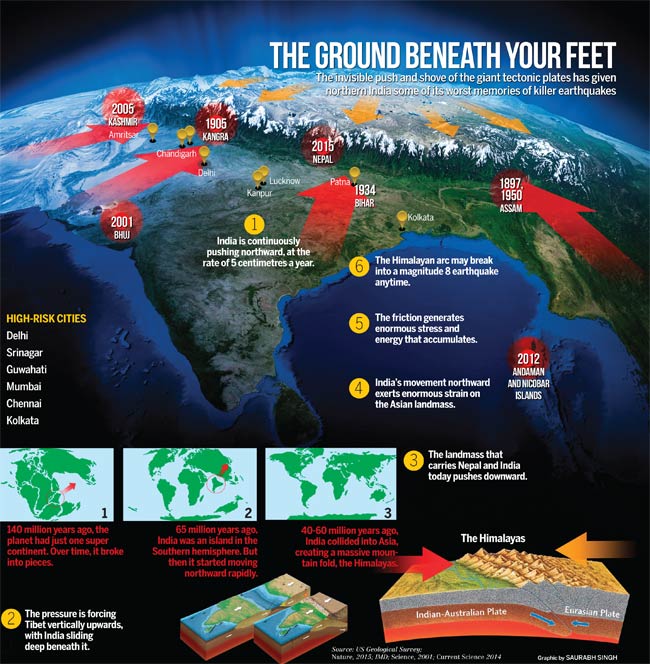

The landmass called the Indian subcontinent is restless beneath its skin. It has been flexing, squeezing and crawling northward for the last 50 million years and perhaps at this very minute, at five centimetres a year. With each invisible thrust, it sends shudders of shock waves across the surface of the earth. And when the relentless push meets stubborn resistance, something has to give: an earthquake, or many-small, big, dramatic or deadly.

More to come

More than 10,000 feared dead and counting. Nepal, in the wake of the catastrophic earthquake over the weekend of April 25-26, has been like a scene from hell. Villages and towns, temples and buildings have turned to rubble. Thousands of homeless and destitute, with loved ones lost, are thronging hospital wards or standing in the streets under pelting rain-without food, clothes, medicine, power or phone service. Even as excavation crew work through the wreckage for signs of life, riverbanks are lit up with funeral pyres. The stench of death hangs over the country.

Monster quakes are waiting in the wings. Scientists say India will not be spared. On April 26, tremors for nearly a minute jolted large swathes of the Gangetic basin-Delhi to Kolkata-and right up to Assam, snuffing out 40 lives, damaging people and property.

There have been 57 earthquakes in the past seven days across India and 122 in the past year, reports the India Meteorological Department. But the Nepal shock, say scientists, has been a warning from earth: there's more to come. But when? Where exactly? How powerful would it be? "This is obviously a big one. But it didn't create a 10-metre surface rupture," says seismologist Supriyo Mitra. "That's what perhaps Delhi will face, with the Himalayas fronting the Capital as the epicentre of an earthquake of magnitude 8 with a 10-metre rupture." The young scientist at Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Kolkata, was in Nepal just a week before for a conference.

Monster quake

Don't Go There!: The Travel Detective's Essential Guide to the Must-Miss Places of the World. When journalist Peter Greenberg wrote his handy travel guide in 2008, it became a global bestseller. But there was a crucial sentence in the book: "The geologically unstable Himalayas have been the source of much devastation, and the worst is yet to come."

It wasn't his personal observation but based on a 2001 research published in the journal Science, conducted by geophysicists from the University of Coloradoat Boulder, US, Roger Bilham and Peter Molnar along with Vinod Kumar Gaur of the Indian Institute for Astrophysics in Bengaluru. The scientists had, for the first time, sent out the warning that at least one 8.1 to 8.3 magnitude earthquake, and perhaps as many as seven, were overdue, threatening millions of people in the region.

"Using satellite technology and GPS equipment, we had found India advancing towards Tibet at a rate of about two metres per century," says Gaur, now honorary scientist with the CSIR Centre for Mathematical Modelling and Computer Simulation in Bengaluru. At the same time, historic data had revealed very few giant earthquakes in the region in the past two centuries, nothing for 500 years in some areas. Dividing the 2,500 km Himalayan arc into 10 regions, each roughly corresponding to a past great earthquake, the team had found that six of these regions had slipped forward 4-6 metres. It implied that each of these regions had built up enough stress inside, like a giant compressed spring, to burst out as a major earthquake. The central Himalayas, Uttarakhand, especially between Dehradun and Kathmandu, are particularly vulnerable. Between 2001 and now, the risks have gone up further. "The big ones can break any day," says Gaur. "We are racing against the clock."

Restless Earth

Beneath the strange movement of the earth lies the drama of plate tectonics, the push-and-shove of giant plates that carry continents and oceans on the solid, outer part of the earth. "About 140 million years ago, there was one giant super continent," says William K. Mohanty, professor of geology and geophysics at IIT-Kharagpur. "Over time, it broke into pieces." Even 65 million years ago, India was an island in the Southern Hemisphere. But then it started moving northward rapidly. As India collided into Asia, it forced Tibet upwards, sliding deep beneath it, and creating a massive fold mountain: the Himalayas. In just 50 million years, Mt Everest rose to a height of just under 9 km.

"But this process hasn't stopped," Mohanty points out. The Himalayas are still rising by 2 cm a year. And India is still moving northward, putting great pressure on the Asian landmass, pushing Tibet upward and winding up the Himalayas like a giant coiled spring. "The spring will snap one day and the Himalayas will lurch forward in a giant earthquake," he adds. A single monster earthquake will create devastation across lakhs of square kilometres and put millions of people at risk. "Massive devastation is foreseen from Afghanistan to Arunachal Pradesh and right down to the Andamans, especially along the overcrowded Gangetic basin."

This tectonic war has given northern India some of its worst memories of killer quakes. The four great earthquakes (magnitude 8.0-8.7) that occurred in the Himalayan region are the 1897 Assam, 1905 Kangra, 1934 Bihar, and the 1950 Assam earthquakes. All occurred due to movements of large blocks of the earth past each other. The Shillong plateau rose 11 metres after the 1897 quake. In Kangra, close to 19,800 people were killed, with tremors felt as far east as Kolkata. The Bihar-Nepal earthquake claimed 16,000 lives. The 1950 Assam earthquake was the 10th largest of the 20th century.

Can we predict?

Way back in the 1960s, when Gaur was a student, studying earthquakes was like groping in the dark. There were no satellite or Global Positioning Systems (GPS). The science of tectonic plates movement was largely unknown. Monitoring earthquake zones to understand movement of plates was done manually, by posting sticks at intervals and checking how far they would move over time. By the late '80s, however, a new wave of instrumentation started, leading the science to far greater levels of precision.

"Today, we can precisely measure the quake zones continuously and to a millimetre by using GPS," says Mitra, "from relative motions to where stresses are building up." There are sophisticated seismometers that can detect vibrations to the tune of 1 angstrom for 0.1 nanometre of movement, or capture images of seismic waves exactly like a CAT scan. "With all these, we can predict where an earthquake will occur, what its intensity and magnitude will be. But what we still cannot tell is when it will take place."

That's because attempts at earthquake prediction have been more of a failure than a success. "In 1975, China had accurately predicted the Haicheng earthquake," says Mohanty. Timely evacuation a day before the earthquake had saved many lives, although 1,328 people had still died. Yet in 1976, one of the most significant failures of prediction was the tragic earthquake of July 27, 1976 in the city of Tangshan, near Beijing, which occurred with no warning, and nearly 250,000 lives were lost. "There are way too many factors at work behind earthquakes," he says.

Earthquakes can originate from different sources: they can be due to tectonic forces at work, they can occur along with volcanic activity, there can be small collapse earthquakes in underground caverns due to landslides or from detonation of a nuclear and/or chemical devices. "They all have different mechanisms," Mohanty adds. Sometimes, before an earthquake, gases such as radon (from radioactive decay of uranium present in most rocks) are emitted, sometimes minor cracks precede a major earthquake, sometimes there is change in the taste or velocity of water in the locality (common in Japan, for instance). And sometimes, there is absolutely no signal.

The rule of thumb still remains what earth scientists call "gaps". Or potential earthquake areas that are under obvious 'strain' yet go without even minor earthquakes-that can take the strain off-for years. That indicates potential for bigger earthquakes. As James Jackson, Head of Earth Sciences at Cambridge University, UK, who was attending a conference in Kathmandu just a week before the earthquake hit, said at a press meet, "(Nepal) was sort of a nightmare waiting to happen. Physically and geologically, what happened is exactly what we thought would happen."