Olive ridley turtle: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Population, dwindling

The Hindu, February 27, 2016

Nivedita Ganguly

Their beaches eroding and disturbed by human interference, fewer turtles are returning to nest every year

Every winter, the Olive Ridley turtles begin returning to the beaches of the Eastern coast to lay their eggs. Theirs is a treacherous journey. Trawlers and fishing boats are a threat for them, lights on shore confuse them, and they are routinely disoriented by human disturbances along the beach. But a more obstinate problem awaits the turtles lucky enough to make it to shore: in many places, beach erosion, which has been more pronounced post cyclone Hudhud, has left them with little place to dig a good nest.

In part the problem is not only the extensive loss of beach due to the severe erosion this season. As the endangered turtles lumber out of the surf in the darkness of a balmy spring night to look for a spot to nest, it is a combination of factors – human disturbances and unfavourable environmental conditions – that are resulting in disorienting these highly sensitive marine creatures.

Forest officials and environmentalists have expressed concern over the dwindling numbers of the eggs spotted on the Visakhapatnam coast this time.

Like every year, the Forest Department has set up two hatcheries – one at R.K. Beach and another at Jodugullapalem – a project being carried out at the cost of Rs 6 lakhs. However, according to the figures provided by the Forest Department, there is a drop in the number of eggs collected in the month of January this year as compared to the corresponding period last year. In 2014, nearly 2,900 eggs were collected in January alone, which were kept in the hatcheries. The figure has dropped to 2,100 this year for the month of January. Overall, 3,078 eggs were collected last year. Interestingly, the maximum egg collection happened in the month of January last year.

“This time, there have been many factors leading to the disturbance of the nesting area of the Oliver Ridley turtles. One of the factors is the massive erosion that has affected major portions of the R.K. Beach, one of the main nesting grounds of the turtles. The beach stretch is now less. To assess the exact extent of the impact on turtle eggs, we will have to wait for a couple of more weeks,” says P. Ram Mohan Rao, Divisional Forest Officer.

Volunteers are keeping guard of the hatcheries and the hatchlings will be released in a month’s time.

Classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) several Olive Ridley turtles lay eggs during this time of the year along the Visakhapatnam coast, considered a sporadic nesting zone. The enclosed hatchery protects the eggs from predators like dogs and visitors to the beach who flock the area unaware of the eggs. Incidentally, the Olive Ridley Turtles take 25 to 30 years to reach adulthood but the survival rate of the young ones is abysmally low.

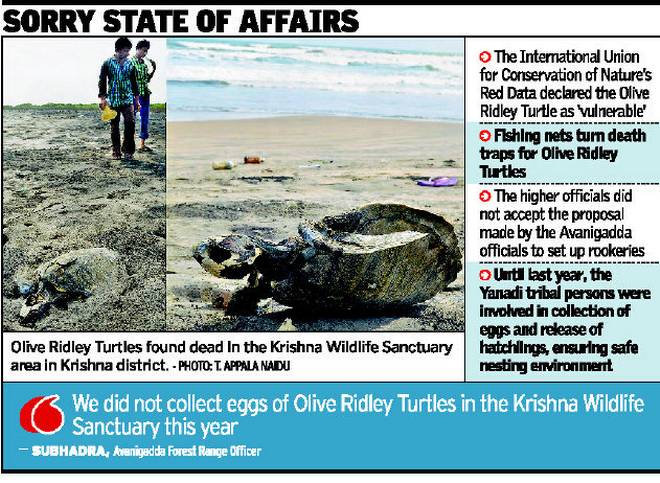

While the shrinking beach stretch is one of the concerns, the alarming frequency of deaths of Olive Ridley turtles along the coast continues to haunt the forest department and environmentalists. “We have recently spotted carcasses of eight Olive Ridley turtles at the beach opposite Sagar Nagar. However, there were no signs of injuries,” Ram Mohan Rao adds.

Researchers and environmentalists, however, have a different theory to share behind the mysteriously dwindling numbers of the turtle eggs. “Erosion may just be one part of the problem. A much larger issue haunts the Olive Ridleys and that is human interference. Tourist activities have increased substantially along the Vizag beaches, especially the R.K. Beach, one of the main nesting grounds of the turtles. Due to this, the fecundity rate (number of eggs laid at a time) goes down. The turtles may be going through fear psychosis due to human disturbances resulting in lower eggs being laid,” points out Prof. D.E. Babu of Dept. of Zoology, Andhra University.

While conservationist say they want to help the turtles, but they cannot agree how. Every time someone proposes a remedy, someone else is quick to rebut on how it will only make things worse. Because the possible solutions involve access to the beach, a crucial part of Vizag’s growing tourism industry, the arguments are bitter.

In fact, experts suggest that fewer and fewer turtles are returning to nest every year, hinting at a possible migration of turtles from the Vizag coast to a different spot. “Mortality rates are high due to the conflict between the turtles and the fishing community,” says Prof. Babu. Interestingly, this time red tidal waves were spotted at certain critical zones of the coast like the R.K. Beach and Lawsons Bay, which are caused due to “harmful plankton” and are hazardous for the aquatic species. “Turtles have a natural tendency to stay away from such zones,” he adds.