Pakistan History: The Mughal Period (1526-1748)

This article is an extract from |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees

with the contents of this article.

NOTE 2: The Pakistanis’ view of their history after 1947 and, more important, of the history of undivided India before that is quite different from how Indian scholars view the histories of these two periods. The readers who uploaded this page did so in order to give others Mr. Wynbrandt’s neutral insight into Pakistan’s history. Indpaedia’s own volunteers have not read the contents of this series of articles (just as it was not possible to read any of the countless other public domain books extracted on Indpaedia).

If you are aware of any facts contrary to what has been uploaded on Indpaedia could you please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name (unless you prefer anonymity).

See also

Indpaedia has uploaded an extensive series of articles about the Pakistan Movement, published in Dawn over the years, and about the various Pakistani wars with India published in the popular media. By clicking the link Pakistan you will be able to see a list of these articles. The Pakistan Movement articles are presently under 'F' (for freedom movement).

The Mughal Period (1526-1748)

The Mughal Empire marked a high point in the history of the sub- continent. While its hold over present-day Pakistan wavered, the empire's military campaigns, governance, trade policies, and cultural achievements had a large impact on the region. Mughal rule rose from the decay of the Delhi Sultanate, a power that never fully recovered from its destruction by Timur in the late 14th century. Yet, paradoxi- cally, it was one of Timur's great-grandsons, Babur (1483-1530), who led the Mughals' ascension. Today he is celebrated as the first of the Six Great Mughals: Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb. The empire grew under an enlightened administrative sys- tem, mansabdari, that included policies of advancement based on abil- ity rather than birth, and religious tolerance for expressions of Hindu devotion and Shi'i ritual. It became one of the largest centralized states in premodern history. The empire's golden age lasted into the 18th century. But poor governance, military setbacks, religious intolerance, and European incursions ultimately brought down the empire by the middle of that century. Mughals would occupy the kingdom's throne for another century, but by then it had neither the size, the power, nor the glory of its former years.

Rise of the Mughals

By the early 16th century what remained of the declining Delhi Sultanate faced threats from traditional enemies — tribal kingdoms, regional dynasties, and Central Asian invaders — and a new foe: the Europeans. These last outsiders came by sea, seeking a direct trade route to Southeast Asia bypassing the hazardous overland Silk Route. Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, who pioneered the route around Africa's Cape of Good Hope, was the first; he landed near Calicut (present-day Kozhikode), on the southwest coast of the subcontinent, in 1498. In 1503 he established the first Portuguese "factory," as the trading posts were called, at Cochin, on the southwestern tip of India. In 1510 the Portuguese took possession of Goa, farther up the coast, and soon established a factory at Diu, in Sind.

At the time, what is today's Pakistan was a patchwork of independent Muslim and Hindu fiefdoms. Many leaders of these small states aspired to regional dominance. Babur of Ferghana was among them. Babur founded the Mughal Empire, and his son, Humayun, spent years rees- tablishing its rule after rebellions splintered the kingdom in the wake of Babur's death. These two monarchs set the foundation upon which the crowning achievements of the Mughal Empire were later built.

Babur

Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad — Babur of Ferghana — was a great-grandson of Timur, the Mongol conqueror. Babur's father was the Timurid king of Ferghana, a Turk-dominated region in present-day eastern Uzbekistan. Though raised in a Turkic culture, Babur was a Mongol. It was this once nomadic group that would give name to a state renowned for its wealth, military prowess, artistic achievement, and enlightened government: the Mughal Empire. Babur inherited the throne of Ferghana at age 12 upon his father's death. He also inherited his father's dream of reconquering Timur's empire and ruling from Samarkand, the capital of Ferghana. But enemies, including his own relatives and the Uzbek Turks, deposed and exiled 14-year-old Babur from Samarkand in 1497.

Over the next few years Babur retook and lost Samarkand twice while building an army, and in 1504 he captured Kabul and Ghazni. After he realized how little income the poor area could generate, in 1505 he proceeded through the Khyber Pass to attack what is now Pakistan, returning with nothing more than some livestock.

In 1507 Babur set out from Kabul to battle the Khalji tribesmen of southeast Afghanistan, going as far south as Kalat in central Baluchistan. Now in control of the trade routes, like his forebears he switched from plundering caravans to taxing them.

The Timurid's greatest adversaries were the Uzbek khans, and the khan in Babur's time was Muhammad Shaybani (r. 1500-10). Shaybani had driven the Timurids from several of their strongholds, including Babur from Samarkand. Babur enlisted as an ally the ruler of Persia, Shah Ismael (ca. 1485-1524), founder of the Shi'i Safavid dynasty, and their forces defeated Shaybani's at the Battle of Merv in 1510, kill- ing the Uzbek khan as he tried to escape. Babur led the allied forces to take Samarkand once more the following year. But Babur, a Shia, did not enjoy the support of the Sunni populace, and, after renewed attacks by the Uzbeks, he abandoned Samarkand again in 1514. For the next five years Babur confined his campaigns to Afghanistan and Baluchistan, but these forays had repercussions in other parts of what is now Pakistan, as well.

Reoccupying Kandahar and Kalat, Babur drove the Mongol ruler of the area, Shah Beg Arghun (r. 1507-22), into Sind, where Jam Firoz, son of the great Samma ruler Jam Nizamuddin (d. 1509), held the throne. Shah Beg defeated the Samma forces, and Jam Firoz retreated to Thatta. Shah Beg built an island fortress at Bhakkar in the Indus River, between present-day Sukkur and Rohri. From here he continued his conquests in Sind. In 1520-21 Shah Beg conquered the Samma capital of Thatta, and Jam Firoz fled to Gujarat, a city in northwestern Punjab and capital of the Gujarat Sultanate, centered in what is today the Indian state of Gujarat. The Arghuns' control of Sind lasted until 1555 and restored the region's cultural ties to Persia.

Conquest of the Punjab and Delhi

In 1519 Babur acquired muskets and artillery and set off for the sub- continent. He first captured the Yusufzai Fort at Bajaur, in what is today the North- West Frontier Province, but failed to conquer the Yusufzai, one of the most powerful Pashtun tribes. Most of northwest Pakistan was under the control of the Gakkars at the time, and Babur next staged a surprise attack on their bastion, Pharwala Fort, near Rawalpindi in Punjab. The Gakkar chief surrendered, and in return Babur recognized their rule of the Potwar Plateau. Thereafter the Mughals could count on Gakkar support for their rule. Returning to his goal to pacify the frontier tribes, Babur married the daughter of the Yusufzaisi's chief, but the tribemen remained rebellious. Changing tactics, Babur mounted a military campaign in the Hashtnagar region of NWFP. Campaigns against tribes along the tributaries of the Indus in Punjab followed, including an effort to eradicate Afghan nobles, many of whom had settled in Punjab during Lodi rule. Punjabis, whom the Afghans had taxed, welcomed their elimination.

Babur's leadership and military prowess drew the attention of nobles seeking a regime change in Delhi. Lodi family members requested Babur's aid in overthrowing Ibrahim I Lodi (r. 1517-26), the sultan of Delhi, in part due to his policy of replacing respected military com- manders with young loyalists. Timur's lands had included Delhi, and as his direct descendant Babur considered the sultanate his birthright. Allying himself with various Lodi leaders, Babur assembled an army and in 1525 marched toward Delhi. Ibrahim Lodi advanced with an army of 100,000 soldiers and 100 elephants to intercept him. The forces met in 1526 at the First Battle of Panipat, about 30 miles north

Polo

Along with many other traditions, the Mughals introduced polo to the subcontinent. The game originated in Central Asia sometime between the sixth century B.C.E. and the first century C.E. Its name is believed to be derived from the word pulu or phulo, meaning "ball" or "ballgame," respectively, in the Balti language of Baltistan, in what is today Pakistan-administered Kashmir. In polo two teams mounted on horseback try to drive a small ball through the opponent's goal using long-handled mallets. It is often compared to the traditional Afghani sport buzkashi (goat grabbing), in which two teams of equestrians attempt to grab the carcass of a headless goat and throw it into a scoring circle.

Now often called the sport of kings, polo became the sport of Persian nobility, and teams might have as many as 100 horsemen. It was also used as a training game for cavalry, as the expert horse- manship required was highly adaptable to the battlefield. Babur is credited with establishing the game in the subcontinent. But by the 19th century polo had largely been forgotten, relegated to a few mountainous pockets in the northern subcontinent. English tea planters and military personnel in Manipur, Bengal, rediscov- ered it in the 1850s. The British developed today's rules (which include having four players per team and dividing the contest into of Delhi. Lodi had superior numbers, but Babur's forces were better equipped and more disciplined. On the first day of battle Ibrahim Lodi and 15,000 men were killed. Babur was proclaimed emperor of Delhi the next day.

Babar's great-grandfather Timur had conquered Delhi and returned to Samarkand. Babur planned to rule from the subcontinent. He recog- nized that it had resources that made it an advantageous seat of power: an abundance of cultivatable lands, plentiful gold and silver, and large numbers of skilled workers in every profession and craft.

Babur's plan to rule from Delhi provoked Rana Sanga of Mewar

(r. 1509-27), northern India's strongest ruler and head of the Rajput

Confederacy, to raise an army of some 210,000 soldiers to oppose

Throughout this time Multan had retained its independence. But in 1526, following a 15-month siege, the Arghun rulers of Sind con- quered the city, sacked it, and massacred the survivors. The remaining inhabitants united behind the former commander of the Multan army and expelled the Arghun governor, then pledged their loyalty to the governor of Punjab, a suzerain of Babur's.

Meanwhile, allies of the former Delhi sultan, Ibrahim Lodi, tried to regain their kingdom. Under the leadership of his brother, Mahmud, during his brief reign as king of Bihar (r. 1528-29), Afghan chiefs of Bihar and Bengal, raised an army to fight Babur. The opposing forces met at the river Ghaghara in 1529 in Babur's last major battle. He emerged victorious, ending the last regional threat to his power.

Humayun

Babur died in 1530 at age 47. He left his Indian territories to Humayun (1508-56), his eldest son, and the Kabul kingdom to his youngest son, Kamran (1509-57). But Babur's hold over the northern regions was weak, and with him gone, restive rulers asserted their independence, among them Bahadur Shah (r. 1526-35, 1536-37), the Afghan ruler of Gujarat; Rajput chiefs; and Sher Khan (1486-1545). The son of a minor Afghan ruler, Sher Khan, who had briefly served in Babur's forces, assumed control of Bihar by the early 1530s.

Determined to regain control of his inherited kingdom, Humayun (r. 1530-40, 1555-56) fought Bahadur Shah and the rebellious Rajputs in a series of skirmishes. He defeated Bahadur Shah in 1535. But Sher Khan led a campaign into Bengal and defeated Humayun's forces at Chausa on the banks of the Ganges in 1539. Taking control of Delhi, he proclaimed himself Sher Shah Sur. At a subsequent encounter at Kanauj in 1540, Humayun's troops fled before the battle even began. Humayun escaped to Lahore and sought protection from his brother, Kamran. With Sher Shah Sur in pursuit, both brothers left Lahore but split up after a dispute at the Jhelum River at Khushab. Kamran went to Kabul, and Humayun went south and joined his mother and brother Hindal in Sind. Here he met his future wife, Hamida Bano. Seeking either an alliance with the Rajput chiefs or their conquest, he and his new wife and followers set out across the Thar Desert to Rajasthan, where they received protection from the rajas of Umarkot (today's Tharparker District in Sind), whose territory included parts of what is today Rajasthan state in India. His son Jalal-ud-Din Akbar was born at Umarkot Fort in 1542.

Seeking more secure refuge in his brother Kamran's domain in Afghanistan, Humayun led his group to Kandahar but came under attack there as well and once again fled, finally finding sanctuary in Persia. Akbar, his son, was left with an aunt in the Kabul kingdom ter- ritories.

Sher Shah Sur

Having chased Humayun to Punjab, Sher Shah Sur (r. 1540-45) de- manded obeisance from the Gakkar rulers, and when they refused he awarded their land to thousands of Afghan tribesmen who had recently settled in the area and to three Baluchi chiefs: Ismael Khan, Fateh Khan, and Ghazi Khan. The Gakkars gathered an army to fight Sher Shah, but were defeated at the Fort of Rewat in Rawalpindi.

During his brief, five-year reign Sher Shah's empire stretched from the Indus Valley through Bengal, and from Kashmir in the north to Chanderi and Benares in central India. He was more concerned about outside invaders than regional rebellions and considered the Mughals a greater threat than Chinggis Khan or Timur had been in their time. Balban and Ala-ud-Din Khalji had established the Delhi Sultanate as a bulwark against Mongol invaders. Sher Shah in turn developed his kingdom to defend the region against the Mughals. He built a massive fort at Rohtas (current-day Rohtak, in the Indian state of Haryana), some three miles around, to defend his kingdom's western borders from the Mughals and Gakkars.

However, his successes as a ruler outshined his military victories. He introduced many reforms embraced by the Mughal rulers and the British colonial overseers who succeeded them. He effectively reorga- nized the state's administrative system, built a network of roads (one of the them, the Grand Trunk Road, extending from the Indus to eastern Bengal, is still in use today), stimulated commerce by overhauling the customs system, and promoted religious tolerance. He also established a professional, salaried army and introduced a system of coins, the rupayya, whose name is still used for coinage in Pakistan, India, and neighboring countries to this day.

Sher Shah was killed in 1545 in an explosion while storming the Rajput hill fortress at Kalinjar in present-day Uttar Pradesh state in central India. On his deathbed he declared his sorrow that he had not destroyed Lahore, eliminating this tempting target of conquerors who used its spoils to continue to fuel their invasions. Some consider Sher Shah the last of the Delhi sultans, and perhaps the greatest.

After Sher Shah's death, his younger son, Jalal Khan, took control as Islam Shah (r. 1545-53) and ruled until his death in 1553. Four more descendants of Sher Shah ruled the dynasty until the last among them, Sikander Shah Sur (r. 1555), was defeated in battle by Humayun.

It was during the final years of the Sur dynasty that Europeans first took military action in the area that is now Pakistan. In 1554 the last of the Arghun, the family that ruled Sind, died. Two Turkish chiefs divided Sind between them, making Thatta and Bhakkar (near pres- ent-day Rohri on the Indus) their capitals. Thatta, a port strategically located at the apex of the Indus delta, had served as the capital of lower Sind since the 14th century. By this time the Portuguese had estab- lished trading posts along the west coast of the subcontinent. One of the new Turkish chiefs sought an alliance with the Portuguese against the other, and the Portuguese agreed to come to his assistance. But by the time the Portuguese sailed into the Indus and anchored, the two chiefs had made peace. Angered that the alliance had been called off, the Portuguese sacked and burned Thatta and the surrounding coun- tryside, slaughtering many.

Humayun's Return

Humayun, now in Persia, persuaded the shah of Persia to back him, as Humayun's father Babur had done with the shah's predecessor. With the shah's support, Humayun attacked and took Kandahar and Kabul from his brother, Kamran. Akbar, Humayun's son, was in his uncle's custody at the time of the attack, and Kamran exposed Akbar at the walls of Kabul Fort during the assault, trying to induce his father to stop the bombardment. Nonetheless Humayun took Kabul and appointed nine- year-old Akbar governor of Kabul. With the city secured, Humayun set off for the subcontinent with Akbar, still eager to reclaim his inherited empire from the ashes of Sher Sur's kingdom. They arrived in 1554.

Kamran had tried to ally himself with Sher Sur's successors but was arrested by the Gakkars and held for Humayun's disposal. On Humayun's orders he was blinded and sent on a pilgrimage to Mecca to contemplate his sins. Humayim conquered Rohtas Fort without a fight, as the Afghan governor and garrison had fled. Humayun captured Lahore, then Sirhind, where he defeated Sikander Sur before claiming Delhi and Agra in 1555.

Inspired by the Safavid art he had encountered while in exile in Persia, Humayun recruited court artists who developed the celebrated Mughal school of painting. He also oversaw the construction of grand edifices that helped define the Mughal style of architecture. But his enjoyment of the regained throne was brief. Humayun died in 1556 after falling down stairs in his library. His tomb in Delhi is one of the finest examples of Mughal architecture in the subcontinent. Some of the details of his life come from memoirs of his sister, daughter of Babur, Gulbadan Begum.

With the Mughal Empire's borders secure, its army powerful, and the framework for its administration in place, the next three emper- ors — Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan — would engineer and preside over the empire's greatest achievements. But during the reign of the last of the Great Mughals, Aurangzeb, the empire's power would begin to decline, never to recover.

Akbar

Akbar the Great (r. 1556-1605) was 13 at the time of his father's death in 1556. His guardian, Bairam Khan, proclaimed him emperor of Hindustan, a term used historically to refer to the Indian subcontinent.

Sher Shah Sur's two nephews, Sikander and Adil, could not over- come their mutual animosity to join forces against Akbar. Adil's army was led by Hemu, a Hindu minister and general. Hemu conquered Agra in October of 1556 and conquered Delhi immediately after when the Mughal general Tardi Beg fled. Hemu took the title of Raja Vikramaditya, literally "sun of valor," borrowing the name of a legend- ary Hindu king. The day after Akbar learned Delhi had fallen, news came that Kabul was in revolt. Against the counsel of all his advisers except his guardian, rather than returning to Kabul to put down the uprising, Akbar marched on Delhi and decisively defeated Hemu's army at the Second Battle of Panipat in 1556.

Akbar's Early Years

In 1560 Akbar took full control of the kingdom from his guardian, whom he sent on a pilgrimage to Mecca to eliminate any possibility of meddling. During the years 1561-76, Akbar reconquered Malwa and Gondwana (in the present-day Indian state of Maharashtra), the Rajput kingdoms, Gujarat, Bihar, and Bengal. This marked the end of the first phase of his campaigns of conquest.

Akbar instituted reforms and treated with respect Rajput rulers who submitted to him, allowing them to retain their power. He used inter- marriage between members of the ruling family and Rajput princesses to cement relationships. He gathered detailed records on agricultural produc- tion and prices in an effort to regulate the economy. For assessing taxes and collecting revenue he adopted the system developed for Sher Shah Sur by Todar Mai, a Rajput king (r. 1560-86). Revenue went mostly to pay military officers, who were responsible for providing for their soldiers and members of the court. Officers, or mansabdars, as these overseers were known, were rotated every three years from territories to keep them from becoming feudal lords. Previously the Arabic term iqta was used for these territorial assignments. By Akbar's reign it had been replaced by the Persian term jagir, as the system would henceforth be known.

The assignment of lands to administer was prone to corruption, as those who made the assignments expected bribes to grant a jagir where productivity was high and the population was not restive. The demand for kickbacks created discontent among military officers. In 1574 Akbar ended the assignment system in the provinces with the oldest links to the empire, including Lahore, Multan, Delhi, and Agra. These areas were managed as khalsa (state-controlled land) for the next five years. Officers in charge got cash salaries rather than a percentage of revenues. But the plan failed, as officers had no incentive to stimulate productivity, and land fell out of cultivation in these areas. Meanwhile, local rulers oppressed and taxed the peasants, leading to depopulation. In response Akbar changed the tax system. Through detailed studies of soil quality, water availability, and other factors for individual parcels, along with local market conditions, assessments were based on what the land was capable of producing. This spurred investment in the land and renewed efforts to improve its productivity.

State and Religion

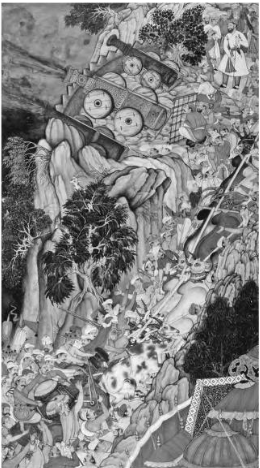

Tolerant of other religions, in 1563 Akbar removed the tax imposed on those who visited Hindu shrines and in 1564 eliminated the jizya, the tax on non-Muslims. He attempted to have local rulers emulate his (opposite page) Bullocks drag siege guns uphill during Akbar's attack on Rathanbhor Fort in 1568. Illustration from the Akbarnama, produced ca. 1590. (Victoria & Albert Museum, London/Art Resource, NY)

THE MANSABDARI AND JAGIRDARI SYSTEMS

Akbar instituted the civil service system upon which the Mughal Empire's administration was based. The system had its roots in the Delhi Sultanate, when rulers such as Ala-ud-Din Khalji and Muhammad ibn Tughluq created a prototypical revenue and payroll plan. Sher Shah Sur reorganized it, and Akbar refined it.

Government officers were organized in 33 levels or grades. Each government officer held the honorific mansabdar (because he had rank) or mansab, if he had sufficient rank. Royal family members typi- cally had exclusive rights to the very top ranks. Those with the rank of Commander of the Five Hundred and above held the title of emir, or "noble." Most officers initially received cash allowances generated from the khalsa, or state-controlled lands, dispensed by the royal treasury. Akbar believed cash payments encouraged loyalty, but the government found it increasingly difficult to manage enough khalsa lands to raise the revenue.

Over time a growing number of officers received jagirs, assigned lands they administered and from which was generated income to pay their salaries and that of their troops as well as to meet other expenses. Akbar and later rulers were eager to prevent officers from creating fiefdoms. Thus the positions were not hereditary, and jagirdaris (those who administered the jagirs) were rotated to new assignments every few years. The system helped stabilize the empire by maintaining government control of property. But it also led to exploitation of the lands since the jagirdaris cared only to maximize income during their tenure. Their oppression led farmers, and later merchants and artisans, to flee jagirs for lands controlled by rajas and zamindars (lords of the land). These local rulers retained their hereditary positions from pre-Mughal times and were allowed to keep their power as long as they remained loyal and provided troops and tribute to the empire. Over time these independent tribal chiefs and kingdoms came to present a major threat to the Mughals as their power declined. nondiscriminatory practices. Though a Muslim himself, after listen- ing to ongoing disagreements of the ulama, or Muslim religious lead- ers, Akbar became disenchanted with Islamic orthodoxy, and created the Hall of Worship, where religious thinkers could come to discuss their religions. He invited Zoroastrians, Christians, Jews, Hindus, and Jains to explain the tenets of their faith. In 1579 he promulgated his Infallibility Decree, which mandated that any conflict among the ulama would be decided by the emperor.

In 1580 nobles and religious leaders in Bihar and Bengal revolted, upset at Akbar's religious unorthodoxy and reduction of their allow- ances. Akbar's half-brother, Mirza Hakim (d. 1585), ruler of Kabul, seized the opportunity and marched on Punjab, but was unsuccess- ful in his effort to capture the Rohtas fort or Lahore. He retreated to avoid Akbar's advancing army, which had arrived at the Sutlej River. Akbar dispatched the great Hindu general Man Singh (1540-1614) to chase Mirza Hakim, while Akbar headed for Kabul, which he occupied, installing his sister, Bakhtunissa Begum, as governor.

By 1582 Akbar had proclaimed himself God's representative on earth and the leader of a new religion, Din-i-Ilahi, the Divine Faith, which combined elements of Islam and Hinduism. He created new rites and ceremonies, some of which offended Muslims. His flirtation with unorthodox theosophies ended by 1590, when he was again practicing Islam. But his tolerance created a long-standing backlash in the Muslim community, which demanded that future emperors be unwavering in their Islamic faith. Leaders would find the most convincing way to demonstrate their orthodoxy was by practicing intolerance toward other religions as well as any unorthodox form of Islam. Thus Akbar's efforts to encourage tolerance and diversity drove the sociopolitical climate in the opposite direction.

Akbar's Middle Years

It was in this period that Akbar built Attock Fort at the point he crossed the Indus, usurping the town of Ohind's position as a major crossing point of the river as well as the Rohtas fort's importance as a frontier bastion.

Punjab and Upper Sind, whose fortunes had declined during the years the jagir system was modified, were now rebounding. Multan retained its importance as a religious center and trade capital, while Sehwan held its position as a commercial hub bustling with trade and industry.

During the years 1584-98, Akbar ruled from Lahore, which remained a center of commerce as well as government. Abdul Fazal (d. 1602), Akbar's friend and court historian, claimed the city had a thousand shops that made sheets and shawls alone. Akbar built a new mint to produce coinage for the realm and constructed a red brick wall around the old city. Some of its original 12 gates still stand.

Akbar's campaigns to subjugate the frontier in Kashmir, Lower Sind, Baluchistan, and parts of the Deccan continued during these years. Much of the agricultural land in Punjab at this time was under direct state control. Jagirdars, as those who oversaw the jagirs were known, were more closely monitored here than those at the fringes of empire.

Akbar was eager to secure the Kabul area for the Mughal Empire. Mirza Hakim had been ruling Kabul under his sister's nominal gover- norship. When he died in 1585, Akbar set out to conquer it, in part to keep it from falling to the Uzbek Turks, who likewise coveted the territory. Akbar, encamped at Attock, sent Man Singh to take over Kabul. Boatmen were brought from the east to ferry forces across the Indus. But Akbar was unable to subdue the border area, primar- ily due to resistance of the Afridi tribe. The Afridi and others in the area were adherents of the Roshanaya movement, a Sufi offshoot, so called for the adopted name of its founder Bayazid Ansari (ca. 1525-82/85), who called himself Pir-i-Roshan (the enlightened one or pir of [Mount] Roshan). Ansari's son Jalala refused to recognize Mughal rule and to permit Akbar's passage through the area. Akbar finally forced Jalala to flee to Chitral, a town in today's NWFP, where he died in 1601. But his absence and death did not dampen restive- ness in the frontier area.

Akbar also attempted to expand the empire northward, but his campaigns in 1585 to conquer the Yusufzais and Kashmir, mounted to take advantage of internecine fighting among Muslim sects there, were unsuccessful. Though the attack failed, a resulting treaty gave the Mughals the right to buy Kashmir's saffron crop. In 1586 Akbar finally conquered Kashmir, making the Mughals the sole purveyor in the saffron market. Profits were vast. But high tax rates imposed on the peasant farmers caused a rebellion in Kashmir, and the tax rates were rolled back.

Akbar's Later Years

Following the Portuguese destruction of Thatta, the city was rebuilt. But renewed civil war among Turkish chiefs of Sind broke out. Sensing an opening, Akbar, back in Lahore from Attock, ordered the governor of Multan to attack lower Sind, and by 1592 the region had been annexed by the Mughal Empire. Baluchistan and Makran were annexed in 1594. The following year the shah of Persia, who had seized Kandahar after helping Humayun regain his empire, gave it to Akbar. All of the north- ern subcontinent was now under his rule, and thus in 1595 Akbar commenced the third and final phase of his campaigns of conquest: marching his forces southward to the Deccan. By 1601 almost all of the subcontinent was Mughal territory.

Under Akbar security was enhanced throughout the empire, lead- ing to increased trade. Commerce was also stimulated by the currency system and mints he founded. A private banking system with letters of credit evolved. Goods from Kashmir and Kabul were shipped through Multan to Thatta's principal port of Larri Bunder. European appetite for dye brought Portuguese and Dutch traders to the region, and the manufacture of indigo dye became a major industry, enriching the kingdom.

Akbar's contributions to the arts are likewise remembered. Though he could neither read nor write, he collected literature and art from around the world and commissioned buildings and monuments. These edifices range from the tomb of his father, Humayun, in Delhi, consid- ered the first great Mughal monument, to the entire city of Fatehpur Sikri (City of Victory), which served as his capital from 1569 to 1584. For his legacy of accomplishments in war and peace, Akbar is consid- ered the greatest Mughal ruler.

Jahangir

Akbar's sole surviving son, Salim, had rebelled against him and tried to set up a kingdom of his own in the Deccan. Akbar nonetheless anointed him as his successor, and Salim ascended to the throne upon Akbar's death in October 1605. He took the title Jahangir (r. 1605-27). Jahangir had spent his formative years around Lahore, his father's capital for much of his reign. His companion as a youngster at home in nearby Sheikhupura was Abdullah Bhatti, the son of a tribal chief whom Akbar had executed. Akbar also killed, in a fit of rage, a woman in his harem, Anarkali, whom Jahangir had fallen in love with. Her tomb is in her eponymous bazaar in Lahore.

Soon after Jahangir's ascension his eldest son, Prince Khusrow, tried wresting control of the empire by laying siege to Lahore. Somewhat paradoxically, Khusrow's attempted coup was supported by nobles angered by the disloyalty Jahangir had shown to his father in trying to establish an independent state in the Deccan. Jahangir came from Agra to battle his son, and their armies met at the Chenab River, with Jahangir's forces prevailing. Prince Khusrow was captured trying to flee the area. As punishment he was blinded and incarcerated, and 700 of his followers were impaled in Lahore.

The leader of the Sikhs, Guru Arjan Dev (1563-1606), was sus- pected of aiding the prince, and his lands were confiscated; he and his sons were imprisoned. Up to that point the Sikhs had been apolitical. Jahangir had Arjan executed in prison, but, after his release, his son Guru Hargobind (1595-1644) formed a Sikh self-defense force, which became a longstanding opponent of the Mughal dynasty.

Meanwhile Abdullah Bhatti, Jahangir's childhood friend, led a force against him to avenge his father's death. Jahangir tried negotiating a settlement, but when that failed, he reluctantly suppressed the uprising. Meanwhile, resistance by the Roshanaya movement, which had begun under his father's reign, continued, and Jalala's successors attacked Peshawar in 1613. The town of Shikarpur in upper Sind became a cen- ter of resistance to the Mughals.

Jahangir's reign was a time of peace and prosperity within his king- dom. The Mughal style of painting reached its zenith under him. But agricultural production began to decline during his reign because of the growing corruption within the jagir system. Jahangir's rule was assisted by his ambitious and beautiful wife, a Persian princess he dubbed Nur Jehan (Light of the World). She had a large hand in administering and ruling the kingdom, as did her family members, including her father, a Persian, and her brother Asaf Khan. Jahangir's third son, Prince Khurram, also part of Nur Jehan's inner circle, married Asaf Khan's daughter, Mumtaz Mahal. In 1615 Prince Khurram conquered the last Rajput fortresses in Mewar. However, the state of Ahmadnagar resisted conquest, and during the campaign Ahmadnagar Fort, which had been captured during Akbar's rule, was retaken from the Mughals. Prince Khurram succeeded in regaining the fort and was given the title Shah Jahan, Lord of the World.

Jahangir's fondness for alcohol was now affecting his health. Nur Jehan wanted her youngest son, Prince Shahriyar, to succeed Jahangir, as he would be the easiest for her to control. Signaling her intent, she gave the hand of her daughter, conceived in an earlier marriage, to Shahriyar. Shah Jahan, who was the popular choice to take over Jahangir's throne, revolted in 1622. But his army was defeated in 1625 by Mahabat Khan, Nur Jehan's general. Nur Jehan, now worried about Mahabat's growing power, accused him of corruption. In response, Mahabat staged an insurrection and captured Jahangir in 1626 while he was en route to Kashmir. Nur rescued Jahangir, but the ruler died in 1627. Asaf Khan, Nur's brother, arrested her, and Shah Jahan was named emperor. Shahriyar was blinded and imprisoned, and Nur gave up statecraft, spending her time overseeing construction of her tomb.

European Trade

During the Mughal era European powers established footholds in the subcontinent. A century after the Portuguese had successfully estab- lished trading posts along the west coast of India and Pakistan, the English, French, and Dutch, hearing of vast profits, followed suit. In 1600, a group of London merchants formed the East India Company (EIC) to trade with India under a charter from Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603).

In 1615 an ambassador from England, Sir Thomas Roe (1581-1644), arrived at Jahangir's court. He was the second such emissary. Seven years earlier England's king James I (1566-1625) had sent Turki- speaking Captain William Hawkins with a request to Jahangir for a trade concession at Surat on the Gujarat coast. Though Hawkins was received graciously and remained for two years, the Portuguese held sway, and permission was denied. Roe had better luck. After three years in residence he won concessions for the EIC as well as permission to build a factory in Surat. Jahangir's largesse to the English angered the Portuguese, who attacked Mughal shipping in retaliation. Jahangir in turn arrested all Portuguese in the empire, closed their churches, and declared war. The Portuguese sued for peace. The English built Surat into a thriving trade center and sought additional outposts in other parts of India.

The Dutch and French formed East India companies of their own, in 1602 and 1664, respectively. Most of the outposts were on the east coast of the subcontinent, putting them closer to the East Indies (pres- ent-day Indonesia) spice trade. Bengal and Bihar became economic centers. The Portuguese and the Dutch went on to fight for control of the East Indies, a war the Dutch would win. The British and French battled over the subcontinent, with the British finally prevailing in the mid- 18th century.

Shah Jahan

Shah Jahan (r. 1627-57) pursued a westward expansionist policy, relo- cating his court to Kabul for two years in pursuit of this goal. During the height of Shah Jahan's reign, the Mughal Empire was the most advanced in the world, the leading light in commerce, culture, and architecture, wealthy beyond the ability to catalog its riches. Among the architectural works created during his reign was the Taj Mahal, the tomb of Jahan's beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal. But Shah Jahan's reign also marked the beginning of the empire's decline, signaled by rebellions in lower Sind, the collapse of Mughal rule in the Deccan, and a stagnating economy. After crippling the agricultural sector by overtaxing farmers, the Mughals began raising taxes on urban enterprises, traders, and artisans. The government entered into trading agreements with European compa- nies to raise revenue. With wealth becoming concentrated and revenues falling, the nobility sought wars as a way of expanding Mughal territory and gaining more revenue, but wars proved increasingly expensive and unsuccessful. Still, the royal court continued in its lavish ways.

One region in which warfare did prove successful was the Deccan, which had slipped from the empire's grasp since Akbar's conquests of 1595-1601. Three of the five Deccan Sultanates — Ahmadnagar, Berar, and Bidar — were reabsorbed into the Mughal Empire. The other two, Golkonda and Bijapur, became tribute-paying states.

Aurangzeb

In 1657, with Shah Jahan suffering a serious illness, a battle for suc- cession erupted among his four sons — Aurangzeb, Shah Shuja, Murad Bakhsh, and Dara Shukoh — from which Aurangzeb emerged victori- ous. He took over Agra and imprisoned his father in Agra Fort until his death in 1666 at age 74. He then pursued his three brothers. Murad was arrested and in 1661 executed. Shah Shuja fled into the jungles of Burma. Dara Shukoh, the eldest, raised an army to fight Aurangzeb but was deserted by erstwhile allies, and in 1569 was captured and executed for heresy by Aurangzeb's forces.

Aurangzeb (1618-1707) was the last of the great Mughals. Under his rule (r. 1658-1707) the Mughal armies led almost constant wars of conquest, and the empire expanded to its largest size. In 1661 the east- ern kingdom of Cooch was annexed by the Mughals. Portuguese pirates were driven from the area after the Mughals conquered the Bengal port of Chittagong in 1666. But the warfare almost bankrupted the empire, and the empire's hold on the new territories was weak. An unpopu- lar ruler, Aurangzeb faced rebellions by the Yusufzais near Peshawar (1667, 1672-76); the Sikhs in Anandpur, in what is today the Indian state of Punjab (beginning in 1668 and lasting for several years); and the Marathas, beginning in 1670. Shiva ji Bhonsle (1630-80), the leader of the Maratha Hindu kingdom, had risen to take over Deccan territory. By 1663 Shiva ji controlled Bijapur territory in the Deccan and Mughal territory in Ahmadnagar. The Mughals' inability to deal effectively with Shiva ji was emblematic of their declining fortunes. Aurangzeb

dispatched his uncle, Shaista Khan, to attack Shiva ji. The Mughals won the initial engagement, but Shiva ji counterattacked and expelled the Mughal forces from the region. Aurangzeb then ordered one of his most powerful generals, the Rajput Jai Singh, to carry on the fight against the Marathas, and the campaign was a success. Shiva ji accepted the terms of surrender and was placed under house arrest at the royal court in Agra. But Shiva ji escaped and regained power in his old territory. He recaptured forts and expanded his dominion to the south, forming a strong independent state.

Meanwhile, Aurangzeb adopted religious policies that created schisms within the empire, further weakening it. A devout Sunni Muslim, he ended the practice of religious tolerance and tried to force the conver- sion of Hindus to Islam. He changed the legal system, making sharia, Islamic law, the law of the land. With the exception of construction of the Badshahi Mosque he also turned his back on the promotion of great works of art and architecture that had characterized Mughal rule up to this time. He banned singers, musicians, and dancers from his court and built few grand monuments or buildings.

The English also gained stronger footholds in the subcontinent dur- ing this period. They received Bombay, which the Portuguese had held, as the wedding dowry of Catherine Henrietta of Braganza (1638-1705),

a Portuguese princess who married King Charles II (1630-85). By then Surat had proved vulnerable, having been sacked twice by Shiva ji (in 1664 and 1670). The English relocated their headquarters to Bombay. They cleared its swamps and by 1677 created a more substantial factory.

Sir Joshua Child, the chairman of the EIC at the time, wanted to strengthen Britain's position in the subcontinent. In 1685 12 English warships were sent to take establish and control fortifications at Chittagong. Mughal forces met and defeated them. In retaliation England blockaded several ports on the Indian west coast. They seized Mughal ships and kept pilgrims from making the hajj to Mecca. Aurangzeb ordered his forces to attack English trading posts. Several including Surat were taken by the Mughals. EIC representatives were killed. The company appealed to Aurangzeb for an end to the attacks and agreed to pay for the seized ships and compensate the Mughal ruler for other damages. In return Aurangzeb pardoned the English and granted them a new trading license in 1690.

At the time, English pirates were active in the region, but the EIC did little to stem their activity. In 1695 English pirates seized a Mughal ship carrying pilgrims and trade profits. In response the Mughal governor of Surat arrested the local head of the EIC and put the city's English citi- zens under custody — in chains — to protect them from angry Muslim residents. On India's east coast, the English were allowed to create a trading post on the Hooghly River in Bengal in 1697. This became the city of Calcutta (present-day Kolkata), the capital of British India from 1858 until 1912. Another major British trade center on the east coast was Madras (present-day Chennai). The British hired local soldiers they called sepoys and formed armed forces for their own protection. Over time local rulers asked the British to lend them the sepoy forces to help with security. In return for concessions and land, the British often agreed; they increasingly became more involved in local affairs and took control of more land.

The frontier area in what is now northwest Pakistan was another region that tested Mughal domination. The Yusufzai had been in rebel- lion since the beginning of Aurangzeb's reign. In 1667 a force of 5,000 Yusufzai mounted a series of invasions into Pakhli (present-day Hazara district). Mughal forces responding to the uprising soundly defeated the rebels. A 1672 revolt by the Satnamis of East Punjab, a fanatical Hindu sect, was also brutally put down. Meanwhile the Jats (not to be confused with the Jats of Afghanistan), an ethnic group in the northern subcontinent whose kingdom centered around Agra, continued causing havoc as they had since Akbar's reign.

Affairs of State

Corruption of the administration system became endemic under Aurangzeb, driving more peasants from the land, lowering state income, and further weakening the empire. Aurangzeb tried to improve the lot of peasants, but his orders were often ignored by landowners and admin- istrators. At the same time his anti-Hindu policies, which included restrictions on religious practices and the desecration and destruction of temples, further alienated his subjects. This encouraged more anti- Mughal activity and helped fuel the Marathas' rebellion. Aurangzeb also alienated the Rajputs by trying to put them under greater state control, which led to a Rajput uprising. Unhappy with the way his son, Prince Akbar, handled the rebellions, Aurangzeb replaced him, and Prince Akbar was subsequently recruited by the Rajputs to lead their forces in revolt against Aurangzeb. But Aurangzeb tricked the Rajput forces into deserting Akbar. However, the war with the Rajputs continued, and Aurangzeb had to cede them some degree of autonomy.

Aurangzeb tracked his rebellious son into the Deccan. Prince Akbar escaped pursuit, but the empire's forces remained in the Deccan for 26 years (1681-1707), and during this time finally captured the Marathas' leader, Shiva ji. The Mughal army boasted 170,000 men, but the force was unwieldy, and its officers were more interested in pursuing leisure at home than engaging in foreign campaigns. Thus the army's power was blunted. Losses mounted in the Deccan. The conflict sapped the empire's strength and will, and it began to suffer setbacks in the north as well. The upper classes were dissatisfied because of deteriorating economic conditions. In 1690, Aurangzeb tried to placate the nobil- ity by promising them ownership of lands under their control. But the flight of the peasants was making land less productive, and, by 1700 the nobles were demanding cash rather than land, and all the local chiefs were in revolt.

The Sikhs coexisted with the Mughals at the beginning of Aurangzeb's reign, mostly due to their own internal dissension. But after Aurangzeb ordered the execution of the ninth Sikh guru, Tegh Bahadur (1621-75), the 10th and last guru, Guru Gobind Singh Gurdwara (1666-1708), formed the Khalsa, the movement's military arm, in 1699. The Khalsa were baptized with water stirred with a dagger. Wearing "the five K's" was mandated: kesha, uncut hair, symbolizing spirituality; kaccha, short pants, signifying self-control and chastity; kangha, comb, symbolizing hygiene and discipline; kara, iron bangle, signifying restraint of action and remembrance of God; and kirpan, dagger, a symbol of dignity and struggles against injustice. Aurangzeb mounted a campaign of suppres- sion against them near the end of his reign, and Mughal forces laid siege to the Sikhs at Amandpur in 1704. The siege was unsuccessful, and the Sikhs were promised safe passage, but the Mughals and their allies slaughtered them once they left their fortifications.

Decline of the Mughals

As Mughal power declined, small independent principalities emerged in the frontier area, Baluchistan, and Sind. Indeed, the Kabul-Ghazni- Peshawar area had never been totally under Mughal control. Aurangzeb had futilely spent more than a year at Hasan Abdal in the frontier area trying to suppress the Yusufzai and other Pashtun tribes.

In 1695 the Ahmedzai clan established a dynasty in Kalat in central Baluchistan that ruled the region's nomads, primarily Baluchis and Brahuis. The ruler was known as the khan of Kalat, and the state as the Khanate. (The British later called this the Brahui Confederacy.) Kalat was strong enough to assert independence from the Persians and the sultans of Delhi who had alternately claimed control of the area in preceding years. Mughal efforts to conquer the area failed. Ahmedzais would remain khans of Kalat until Kalat agreed to join the newly inde- pendent Pakistan in 1948.

Maritime commerce, which had been an important part of the empire's economy, was also in decline during this period. The harbor at Thatta and other Sind ports were filling with silt despite Mughal efforts under Aurangzeb and his successor to clear them. And ports in nearby Gujarat faced attacks by Marathas, who gained control over western coastal waters.

Aurangzeb died in 1707 at the age of 80. After brief infighting 63- year-old Shah Alam (r. 1707-12), Aurangzeb's most capable son and the former governor of Kabul and Peshawar, took the throne. He assumed the title Bahadur Shah but ruled only five years before he died in Lahore. Bahadur Shah's death marked the end of the Mughal Empire's glory. Looting broke out in Lahore as armies of those vying for succes- sion converged on the city to gain control of the empire.

Of Bahadur's four sons, Prince Azam was most admired. His three brothers were encouraged by a nobleman to challenge him for rule. Azam drowned with his elephant, and the nobleman arranged for the least capable of the siblings, Jahandur Shah, to take the throne so his backers could control the empire. Azam's son, Farukkhsiyar (1683- 1719) defeated Jahandur with the help of two officers, the Sayyid brothers. When Farukkhsiyar took the throne in 1713, it was under the control of the Sayyid brothers. During his reign the Europeans, espe- cially the British, were able to get favorable treatment for their trading ventures by bribing officials. In 1715-16 the Mughals achieved a final victory in eastern Punjab over the Sikhs, who were led by Banda Singh Bahadur (1670-1716). Banda and thousands of Sikhs were tortured and killed. But Sikh unrest continued, destabilizing the kingdom and com- promising trade, with bands of Sikh robbers raiding the caravans.

In 1719 the Sayyids had Farukkhsiyar incarcerated and killed. The Sayyids installed two subsequent puppet regents in the same year before Muhammad Shah (r. 1719-48), a 20-year-old grandson of Bahadur Shah, was named ruler. The Sayyid brothers' ruthless machinations caused their own deaths, which came within a year of Muhammad's ascension. Muhammad's rule lasted almost 30 years, marked by contin- ued loss of territory and power as those around him grabbed what they could from the disintegrating empire.

The mid- 18th century marked the nadir of Muslim fortunes in the subcontinent. One of the leading reformers who attempted to halt the decline of Muslim rule and revive its intellectual traditions was Shah Waliullah (1703-62). After completing Islamic studies in Mecca in 1734, he returned to the subcontinent and began preaching, calling on Muslims to return to the pure life as exemplified by the words and deeds of the prophet Muhammad. His most important accomplishment was the translation of the Qur'an into Persian. After Shah Waliullah's death, his son, Shah Abdul Aziz (1746-1823), continued his work with the help of dedicated assistants.

As the Mughal Empire dissolved, it was kept from chaos by the able administration of the now-autonomous states that were taken over by local governors. But the weakened territory was again vulnerable to invasion. In 1735 the Persian king, Nadir Shah (r. 1736-47), took advantage of the power vacuum. He acquired European arms, which he used in a campaign of conquest of his neighbors to the east and former Mughal strongholds. He defeated Kabul and then advanced on Punjab. The territory submitted without resistance, but Nadir Shah plundered and looted Punjab nonetheless. Lahore was spared carnage after the rich inhabitants paid for their city's safety. Nadir Shah next conquered Delhi. He kept Muhammad Shah on the throne as a puppet, receiving in return a very rich tribute that included the famed Koh-i-noor dia- mond and the Peacock Throne of Shah Jahan. But Delhi was not spared as Lahore had been, and the city was depopulated between 1738 and 1739. Karachi, today Pakistan's major port, was first mentioned in an account of Nadir Shah's officers who made use of the harbor.

A decade after Nadir Shah's incursion, Ahmed Shah Abdali (ca. 1723-73), an officer under Nadir, followed a similar invasion path, but was defeated at Sirhind, in southeast Punjab, by Muhammad Shah's son. The Persians retreated across the Indus. This was the last victory the Mughals achieved over foreign invaders. The death of Muhammad Shah in 1748 marked the end of Mughal power.

Half a dozen more Mughals took the throne after Muhammad Shah, but they presided over an empire in name alone, continuously shrink- ing and losing power, under siege by regional rulers and the European powers that were increasingly gaining power over the subcontinent.