Irulas of Chingleput

Irulas of Chingleput

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

North and South Arcot. The Irulas, or Villiyans (bowmen), who have settled in the town of Chingleput, about fifty miles distant from Madras, have attained to a higher degree of civilisation than the jungle Irulas of the Nīlgiris, and are defined, in the Census Report, 1901, as a semi-Brāhmanised forest tribe, who speak a corrupt Tamil.

In a note on the Irulas, Mackenzie writes as follows. “After the Yuga Pralayam (deluge, or change from one Yuga to another) the Villars or Irulans, Malayans, and Vedans, supposed to be descendants of a Rishi under the influence of a malignant curse, were living in the forests in a state of nature, though they have now taken to wearing some kind of covering—males putting on skins, and females stitched leaves. Roots, wild fruits, and honey constitute their dietary, and cooked rice is always rejected, even when gratuitously offered. They have no clear ideas about God, though they offer rice (wild variety) to the goddess Kanniamma. The legend runs that a Rishi, Mala Rishi by name, seeing that these people were much bothered by wild beasts, took pity on them, and for a time lived with them. He mixed freely with their women, and as the result, several children were born, who were also molested by wild animals. To free them from these, the Rishi advised them to do pūja (worship) to Kanniamma. Several other Rishis are also believed to have lived freely in their midst, and, as a result, several new castes arose, among which were the Yānādis, who have come into towns, take food from other castes, eat cooked rice, and imitate the people amidst whom they happen to live.” In which respects the Irula is now following the example of the Yānādi.

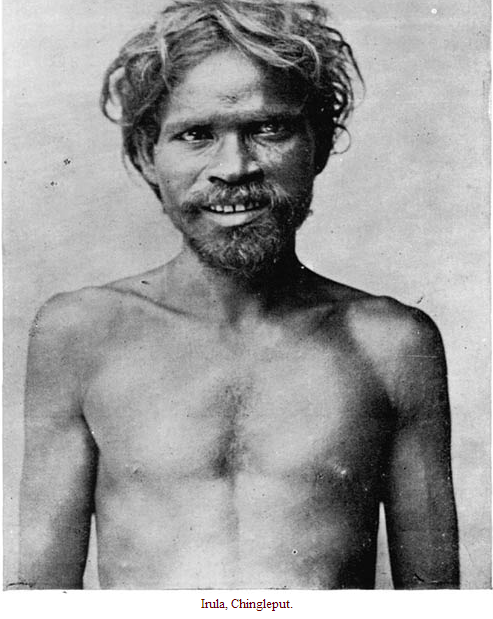

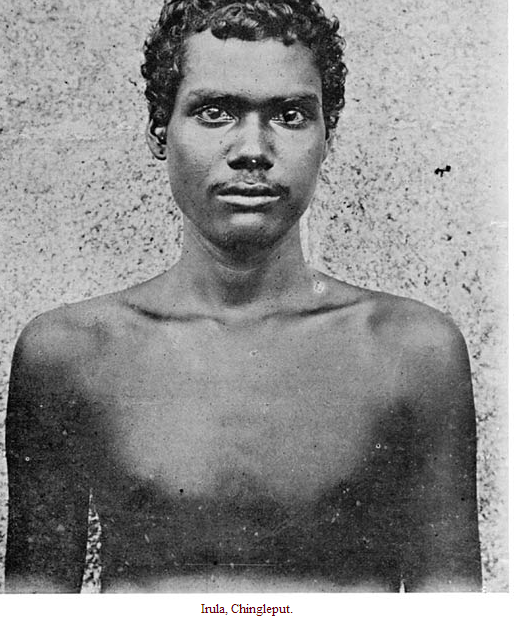

Many of the Chingleput Irulas are very dark-skinned, with narrow chests, thin bodies, and flabby muscles, reminding me, in their general aspect, of the Yānādis of Nellore. Clothing is, in the men, reduced to a minimum—dhūti, and langūti of dirty white cotton cloth, or a narrow strip of gaudy Manchester piece-good. The hair is worn long and ragged, or shaved, with kudimi, in imitation of the higher classes. The moustache is slight, and the beard billy-goaty. Some of the men are tattooed with a blue dot on the glabella, or vertical mid-frontal line. For ornaments they have a stick in the helix, or simple ornament in the ear-lobe.

Their chief source of livelihood is husking paddy (rice), but they also gather sticks for sale as firewood in return for pice, rice, and sour fermented rice gruel, which is kept by the higher classes for cattle. This gruel is also highly appreciated by the Yānādis. While husking rice, they eat the bran, and, if not carefully watched, will steal as much of the rice as they can manage to secrete about themselves. As an addition to their plain dietary they catch field (Jerboa) rats, which they dig out with long sticks, after they have been asphyxiated with smoke blown into their tunnels through a small hole in an earthen pot filled with dried leaves, which are set on fire. When the nest is dug out, they find material for a meat and vegetable curry in the dead rats, with the hoarded store of rice or other grain. They feast on the bodies of winged white-ants (Termites), which they search with torch-lights at the time of their seasonal epidemic appearance. Some years ago a theft occurred in my house at night, and it was proved by a plaster cast of a foot-print in the mud produced by a nocturnal shower that one of my gardeners, who did not live on the spot, had been on the prowl. The explanation was that he had been collecting as a food-stuff the carcases of the winged ants, which had that evening appeared in myriads.

Some Irulas are herbalists, and are believed to have the powers of curing certain diseases, snake-poisoning, and the bites of rats and insects.

Occasionally the Irulas collect the leaves of the banyan, Butea frondosa, or lotus, for sale as food-platters, and they will eat the refuse food left on the platters by Brāhmans and other higher classes. They freely enter the houses of Brāhmans and non-Brāhman castes, and are not considered as carrying pollution. They have no fixed place of abode, which they often change. Some live in low, palmyra-thatched huts of small dimensions; others under a tree, in an open place, in ruined buildings, or the street pials (verandah) of houses. Their domestic utensils consist of a few pots, one or two winnows, scythes, a crow-bar, a piece of flint and steel for making fire, and a dirty bag for tobacco and betel. In making fire, an angular fragment of quartz is held against a small piece of pith, and dexterously struck with an iron implement so that the spark falls on the pith, which can be rapidly blown into a blaze. To keep the children warm in the so-called cold season (with a minimum of 58° to 60°), they put their babies near the fire in pits dug in the ground.

For marital purposes they recognise tribal sub-divisions in a very vague way. Marriage is not a very impressive ceremonial. The bridegroom has to present new cloths to the bride, and his future father- and mother-in-law. The cloth given to the last-named is called the pāl kuli (milk money) for having nursed the bride. Marriage is celebrated on any day, except Saturday. A very modest banquet, in proportion to their slender means, is held, and toddy provided, if the state of the finances will run to it. Towards evening the bride and bridegroom stand in front of the house, and the latter ties the tāli, which consists of a bead necklace with a round brass disc. In the case of a marriage which took place during my visit, the bride had been wearing her new bridal cloth for a month before the event.

The Irulas worship periodically Kanniamma, their tribal deity, and Māri, the general goddess of epidemic disease. The deity is represented by five pots arranged in the form of a square, with a single pot in the centre, filled with turmeric water. Close to these a lamp is lighted, and raw rice, jaggery (crude sugar), rice flour, betel leaves and areca nuts are offered before it. Māri is represented by a white rag flag dyed with turmeric, hoisted on a bamboo in an open space near their dwellings, to which fowls, sheep, and other cooked articles, are offered. The dead are buried lying flat on the face, with the head to the north, and the face turned towards the east. When the grave has been half filled in, they throw into it a prickly-pear (Opuntia Dillenii) shrub, and make a mound over it. Around this they place a row or two of prickly-pear stems to keep off jackals. No monumental stone is placed over the grave.

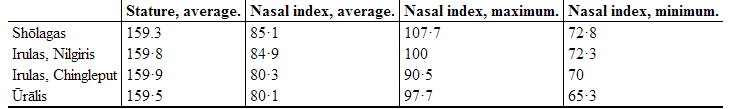

By means of the following table a comparison can be readily made between the stature and nasal index of the jungle Shōlagas and Nīlgiri Irulas, and of the more civilised Irulas of Chingleput and Ūrālis of Coimbatore:—

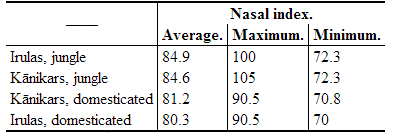

The table shows clearly that, while all the four tribes are of short and uniform stature, the nasal index, both as regards average, maximum and minimum, is higher in the Shōlagas and Irulas of the Nīlgiri jungles than in the more domesticated Irulas of Chingleput [387]and Ūrālis. In brief, the two former, who have mingled less with the outside world, retain the archaic type of platyrhine nose to a greater extent than the two latter. The reduction of platyrhiny, as the result of civilisation and emergence from the jungle to the vicinity of towns, is still further brought out by the following figures relating to the two classes of Irulas, and the Kānikars of Travancore, who still live a jungle life, and those who have removed to the outskirts of a populous town:—

The Irulas of North Arcot are closely related to those of Chingleput. Concerning them, Mr. H. A. Stuart writes as follows. “Many members of this forest tribe have taken to agriculture in the neighbouring villages, but the majority still keep to the hills, living upon roots and wild animals, and bartering forest produce for a few rags or a small quantity of grain. When opportunity offers, they indulge in cattle theft and robbery. They disclaim any connection with the Yānādis, whom they hate. Their aversion is such that they will not even allow a Yānādi to see them eating. They offer worship to the Sapta Kannikais or seven virgins, whom they represent in the form of an earthenware oil-lamp, which they often place under the bandāri (Dodonœa viscosa ?), which is regarded by them as sacred. These lamps are made by ordinary village potters, who, however, are obliged to knead the clay with their hands, and not with their feet.

Sometimes they place these representatives of their goddess in caves, but, wherever they place them, no Pariah or Yānādi can be allowed to approach. The chief occasion of worship, as with the Kurumbas and Yānādis, is at the head-shaving ceremony of children. All children at these times, who are less than ten years old, are collected, and the maternal uncle of each cuts off one lock of hair, which is fastened to a ragi (Ficus religiosa) bough. They rarely contract marriages, the voluntary association of men and women being terminable at the will of either. The more civilised, however, imitate the Hindu cultivating castes by tying a gold bead, stuck on a thread, round the bride’s neck, but the marriage tie thus formed is easily broken. They always bury their dead. Some Irulas are credited with supernatural powers, and are applied to by low Sūdras for advice. The ceremony is called suthi or rangam. The medium affects to be possessed by the goddess, and utters unmeaning sounds, being, they say, unconscious all the while. A few of his companions pretend to understand with difficulty the meaning of his words, and interpret them to the inquirer. The Irulas never allow any sort of music during their ceremonies, nor will they wear shoes, or cover their body with more than the scantiest rag. Even in the coldest and dampest weather, they prefer the warmth of a fire to that of a cumbly (blanket). They refuse even to cover an infant with a cloth, but dig a small hollow in the ground, and lay the newly-born babe in it upon a few leaves of the bandāri.”

There are two classes of Irulas in the North Arcot district, of which one lives in towns and villages, and the other leads a jungle life. Among the latter, as found near Kuppam, there are two distinct divisions, called Īswaran Vagaira and Dharmarāja. The former set up a stone beneath a temporary hut, and worship it by offering cooked rice and cocoanuts on unam (Lettsomia elliptica) leaves. The god Dharmarāja is represented by a vessel instead of a stone, and the offerings are placed in a basket. In the jungle section, a woman may marry her deceased husband’s brother. The dead are buried face upwards, and three stones are set up over the grave.

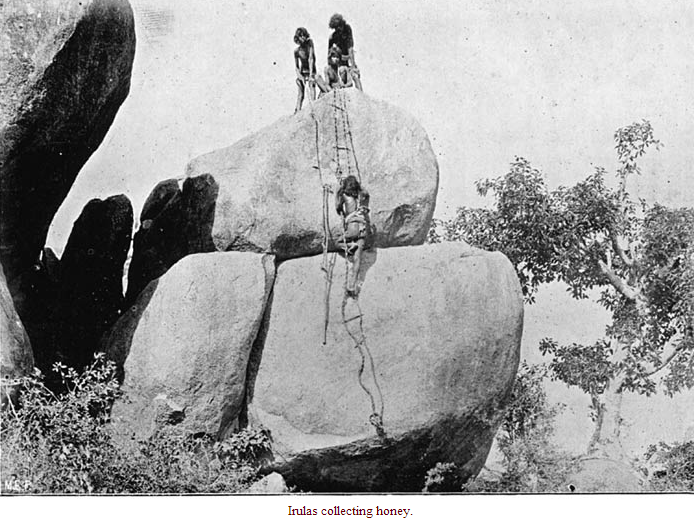

The Irulas of South Arcot, Mr. Francis writes, “are chiefly found about the Gingee hills, talk a corrupt Tamil, are very dark skinned, have very curly hair, never shave their heads, and never wear turbans or sandals. They dwell in scattered huts—never more than two or three in one place—which are little, round, thatched hovels, with a low doorway through which one can just crawl, built among the fields. They subsist by watching crops, baling water from wells, and, when times are hard, by crime of a mild kind. In Villupuram and Tirukkōyilūr tāluks, and round Gingee, they commit burglaries in a mild and unscientific manner if the season is bad, and they are pressed by want, but, if the ground-nut crop is a good one, they behave themselves. They are perhaps the poorest and most miserable community in the district. Only one or two of them own any land, and that is only dry land. They snare hares now and again, and collect the honey of the wild bees by letting themselves down the face of cliffs at night by ladders made of twisted creepers. Some of them are prostitutes, and used to display their charms in a shameless manner at the Chettipālaiyam market near Gingee, decked out in quantities of cheap jewellery, and with their eyelids darkened in clumsy imitation of their sisters of the same profession in other castes.

There is little ceremony at a wedding. The old men of the caste fix the auspicious day, the bridegroom brings a few presents, a pandal (booth) is made, a tāli is tied, and there is a feast to the relations. The rites at births and deaths are equally simple. The dead are usually buried, lying face upwards, a stone and some thorns being placed over the grave to keep off jackals. On the eleventh day after the death, the eldest son ties a cloth round his head—a thing which is otherwise never worn—and a little rice is coloured with saffron (turmeric) and then thrown into water. This is called casting away the sin, and ill-luck would befall the eldest son if the ceremony were omitted. The Irulans pay homage to almost all the grāmadēvatas (village deities), but probably the seven Kannimars are their favourite deities.” As already indicated, the Irulas, like the Yerukalas, indulge in soothsaying. The Yerukala fortune-teller goes about with her basket, cowry shells, and rod, and will carry out the work of her profession anywhere, at any time, and any number of times in a day.

The Irula, on the contrary, remains at his home, and will only tell fortunes close to his hut, or near the hut where his gods are kept. In case of sickness, people of all classes come to consult the Irula fortune-teller, whose occupation is known as Kannimar varniththal. Taking up his drum, he warms it over the fire, or exposes it to the heat of the sun. When it is sufficiently dry to vibrate to his satisfaction, Kannimar is worshipped by breaking a cocoanut, and burning camphor and incense. Closing his eyes, the Irula beats the drum, and shakes his head about, while his wife, who stands near him, sprinkles turmeric water over him. After a few minutes, bells are tied to his right wrist. In about a quarter of an hour he begins to shiver, and breaks out in a profuse perspiration. This is a sure sign that he is possessed by Kanniamman. His wife unties his kudumi (tuft of hair), the shaking of the head becomes more violent, he breathes rapidly, and hisses like a snake. His wife praises Kannimar. Gradually the man becomes calmer, and addresses those around him as if he were the goddess, saying, “Oh! children. I have come down on my car, which is decorated with mango flowers, margosa and jasmine. You need fear nothing so long as I exist, and you worship me. This country will be prosperous, and the people will continue to be happy. Ere long my precious car, immersed in the tank (pond) on the hill, will be taken out, and after that the country will become more prosperous,” and so on. Questions are generally put to the inspired man, not directly, but through his wife. Occasionally, even when no client has come to consult him, the Irula will take up his drum towards dusk, and chant the praises of Kannimar, sometimes for hours at a stretch, with a crowd of Irulas collected round him.

The name Shikāri (hunter) is occasionally adopted as a synonym for Irula. And, in South Arcot, some Irulas call themselves Tēn (honey) Vanniyans or Vana (forest) Pallis.

Irula (darkness or night).—An exogamous sept of Kuruba.

Tackled invasion by Burmese Pythons in Thailand and the USA

Oppili P & Priya Menon, TN snake catchers come to US' aid, Jan 28, 2017: The Times of India

Two Irula Tribals Flown To Florida To Tackle Invasion Of Burmese Pythons

They were flown to Thailand when a group of researchers working on a snake project needed help catching cobras and kraits there. And now, when Florida is struggling to tackle an invasion of Burmese pythons, it's once again Masi Sadaiyan and Vadivel Gopal, two members of a snake-catching tribe from Tamil Nadu called the Irula, who have been flown to the rescue.

The two, who have been working with biologists from the University of Florida since January 6, have already captured 13 Burmese pythons, castaways of the pet trade that have become a threat to native species, especially birds and rabbits. One of the captured pythons was a 16-foot female, according to reports.

“The officials there tried all kinds of methods and have finally taken snake-catchers from here,“ says says Yamini Bhaskar, assistant director Madras Crocodile Bank Trust (MCBT) -Centre for Herpetology. According to Washington Post, Florida paid $69,000 to hire the Irula men and their translators and fly them to the Everglades. For the community , it's a proud moment as their skills are finally getting international recognition. Known as the last “forest scientists“ of the world, the Irulas have been snake catchers for generations. Their ability to track snakes -without using any sophisticated equipment and relying only on their own powers of intuition and observation -is what makes them much sought after.

Both Sadaiyan and Gopal, who are in their early 50s, are members of the Irula Snake Catchers' Industrial Cooperative Society (ISCICS), which is located on the premises of MCBT. Conservationist and herpetologist Romulus Whitaker established the Society in 1978 for the welfare of the Ir ula community who were deprived of their traditional livelihood when export of snake skins from India was banned in 1975 under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972. The Irulas now extract and freezedry venom to sell it to anti-venom producing laboratories.

Mari, an Irula and experienced snake catcher, says that when they track a snake, they look out for three things -its scales on the soil, shed skin and the droppings. “These are the three vital clues, which indicate the presence or movement of snakes,“ he says.

Mari's wife Suseela said: “My husband's father taught him how to catch snakes, and he mastered it over the years. I am proud that his skills are in demand in the US.“ CHARMING BUSINESS: According to Washington Post, Florida paid $69,000 to hire the Irula men and their translators and fly them there