Skardu

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Skardu

Salvaging heritage and helping the people

By Rina Saeed Khan

The conversion of the fort into a hotel was painstakingly done so as to remain faithful to its original structure and character. What is surprising is that all this was achieved only in four to five years –– it goes to show what can be done in a short period, given expertise and funding

Skardu, the capital of Baltistan (Pakistan-occupied Kashmir), lies in a wide valley ringed by snow covered peaks and surrounded by a mountain desert. The light, like the landscape, seems softer, more diffused than elsewhere in the Northern Areas. Our destination, however, was Shigar, a picturesque green valley around thirty minutes’ drive away, which lies on the way to the famous Baltoro glacier and K-2.

The settlement of Shigar has been selected by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) for their Historic Cities Support Programme. This programme goes beyond the mere restoration of monuments, and engages in activities related to the adaptive reuse of buildings, directed at improving local living conditions.

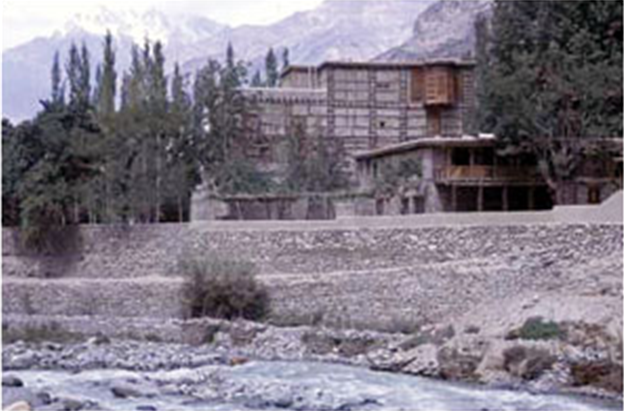

In Shigar, the programme has restored the local Raja’s fort palace, converting it into an exclusive guesthouse. This fort palace was crumbling, almost in ruins when the Raja handed it over to the NGO. In return, it built him a rather elegant house close by the hotel, in the style of the traditional architecture of the area but with all the modern amenities.

Unlike other commercial hotels, the ‘Shigar Fort Residence’ ploughs back all its profits into the local community. Already, Shigar valley is benefiting from this project as locals are trained and employed and local handicrafts are sourced for use in the hotel. This up market hotel is already attracting international tourists to this culturally rich region, which is also home to some of the highest mountains on earth.

In 2006, Aga Khan finally inaugurated the Shigar Fort hotel, although it has been operating now since 2005. In September, 2006, the Unesco Regional Advisor for Culture in Asia and the Pacific announced that Shigar Fort has been honoured with the Award of Excellence for Culture Heritage Conservation. The Norwegian government was the main partner in the restoration of the fort. Funding was also provided by the governments of Germany, Greece, Japan, Pakistan, Spain and Switzerland.

Baltistan is often called ‘Little Tibet’ and its architecture reflects the area’s historic links with that region. In fact, Baltistan lies at the junction of the Islamic and Buddhist worlds and its inhabitants were mostly Buddhist before converting to Islam. One can find the remains of old monasteries on the ridges and the wooden carvings on the doors and pillars use Buddhist motifs like the lotus flower. Shigar Fort has plenty of these motifs on its carved beams and doorways.

Shigar is a lush green valley located near the river’s edge. It was ruled for centuries by the Amacha dynasty, which had its origins in the Hamacha tribe of Hunza. Some believe that a young man from Hunza with the name of Amacha came to Shigar using a passage across the Hispar glacier. Other writers think that as the Hamacha tribe was massacred in Hunza, some members managed to flee to Shigar where they gained power and won recognition as the Amacha in the 13-14th centuries.

Raja Hassan Khan ascended the throne in 1634, and with the permission of the Mughal emperor Shah Jehan, brought various artisans including shawl weavers, carpenters, goldsmiths and stone-carvers from Kashmir to Shigar.

He built Shigar Fort upon a huge boulder and it is known locally as Fongkha ––– literally, ‘the palace on the rock’. The rock is the first thing most visitors notice upon arrival at the fort: the large boulder protrudes obtrusively from the walls at the entrance.

The fort itself was designed as a cribbage structure with interlacing wooden beams (which protects the structure from earthquakes). Its three stories are built on a massive platform using the rock as its foundation. Walking around the well-kept garden and gazing up at its newly renovated stone walls with their crisscrossing wooden beams, one could hardly believe that it had all been in complete shambles when the present Raja, Mohammad Ali Shah, gifted it to the NGO back in 1999.

Indeed, the fort had been in a dilapidated condition for a very long time. The Raja had abandoned it back in the 1950s in favour of an annexe he built for himself nearby. Today these have been turned into a kitchen and dining room. The Raja has also leased his large garden and orchard to the AKTC and they have built some more guestrooms around it.

The restoration has led to a revitalisation of the surrounding villages, where the NGO has helped to install proper sanitation and clean drinking water. In the years to come the fort will generate the necessary funds for its future maintenance and for supporting community projects

“This was a completely feudal society and the Raja’s rule was absolute. Today, of course, there are no more fiefdoms in the Northern Areas (since the mid-1970s) and the people are adjusting to this change,” says Safiullah Baig, the deputy manager of the AKCSP.

“Yet, the forts and palaces are all part of the people’s heritage, their identity and we want the local people to take pride in them and feel a sense of ownership. In Hunza, the local people now refer to the Baltit Fort museum, which once belonged to the Mir, as ‘our fort’. When we completed Shigar Fort’s restoration, the Raja asked us ‘if you don’t mind, could I have a look around’? This was his home, where he grew up and yet he is comfortable with the change.” All the young architects and designers who worked on the fort are also from the Northern Areas and have been given special training by the AKTC.

The fort’s garden overlooks a rushing stream and most of the rooms on one side have views of this picturesque scene. Inside the newly renovated fort, spotlights illuminate the reception area which is located on the first floor. It is quite gloomy inside, although some natural light filters in through a small window in the thick walls. There is a museum here, in the oldest part of the fort. A smattering of antiques ––– old utensils, wooden containers and carved pillars are displayed in a tasteful manner.

The terrace outside the first floor leads to the newly renovated bedrooms. A peak inside revealed an elegant room with a comfortable bed, small desk, stylish lamps and rolled up blinds on the small windows. In the walls were recesses displaying antiques. A small bathroom with modern amenities is attached to each bedroom. It is really amazing that people can enjoy the 21st century luxury in a 17th century fort!

There are thirteen rooms in the fort and each is different. They are of varying sizes; some have bed niches, others have screens or woodcarvings. Yet they are all comfortable and inviting, with soft hand-woven textiles, wooden floors and lime washed walls. The architects have tried to retain as much as possible of the fort’s authentic character.

Modern furniture is minimal -–– the focus is on the spectacular woodwork and the artefacts of the region which have been placed sparingly in each room. They say that good design is what you leave out, and it is obvious that the designers have put a lot of thought into each room.

Many hours of meticulous planning and attention to detail have gone into each room. “We have used local materials and handicrafts,” explained Shehnaz Ismail, who is in charge of the textiles, crockery, and the discreet interiors of the hotel. “The idea is to be faithful to the culture of this region. This is not a luxurious hotel ––– it is really for discerning clients who are looking for authenticity.”

Ismail has initiated a project in which locals from the community are taught new designs and asked to weave woollen rugs. She hopes to revive traditional skills ––– the handicrafts can be bought by tourists as souvenirs.

“This project is unique in Pakistan. It was done in a relatively fragile building fabric,” explained Masood Khan, one of the leading architects of the project. “We had to be very careful and make sure the installations are as reversible as possible. We did not want the modern additions to invade the fabric of the building.”

Guests staying at Shigar Fort are expected to treat the fort with the kind of respect and loving care that the staff accords to it. Thus, for instance, eating in the bedrooms is strictly forbidden.

The conversion of the fort into a hotel was painstakingly done so as to remain faithful to its original structure and character. What is surprising is that all this was achieved only in four to five years -––– it goes to show what can be done in a short period, given expertise and funding and the will to work.

Already, the restoration has led to a revitalisation of the surrounding villages, where the NGO has helped to install proper sanitation and clean drinking water. In the years to come the fort will generate the necessary funds for its future maintenance and for supporting community projects. This project could really become a model for the renovation of dilapidated forts and palaces not only in the Northern Areas, but all over Pakistan.

HCSP Historic Cities Support Programme Baltit etc Historic Cities Support Programme The HCSP was established by the Aga Khan Development Network in 1992. It undertakes the conservation and rehabilitation of historical buildings and urban spaces in ways that serve to catalyse social, economic and cultural development. Since its inception, over twenty distinct projects have been initiated in several different regions of the Islamic world.

In Kabul, the HCSP is leading a project to rehabilitate the Babur Garden, the oldest Mughal 'Paradise garden', which contains the tomb of 16th century emperor Babur. In the Northern Areas of Pakistan, projects for the rehabilitation and reuse of historic forts, landmark buildings and traditional settlements, as well as the promotion of traditional crafts and building techniques, have helped transform poor communities into relatively prosperous ones. In 2004, the Baltit Fort restoration project in Hunza received the UNESCO award for excellence.

The restored Baltit Fort, now a museum, attracts over 20,000 visitors annually, half of which are from outside the country. –– R.S.K

Remembering the defenders of Skardu

Harbans Singh , Remembering the defenders of Skardu "Daily Excelsior" 13/8/2015

August 14, 1948 marked the end of a heroic, and often lonely, resistance of the Skardu garrison. It had taken seven long and grueling months but in the end with the last of the ammunition exhausted there was little choice but to surrender. Unknown to leaders in Delhi then, its reverberations were to be felt long after in the history of the region. Today it is a potent tool for China to claim role in South Asia for the proposed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor connecting Kashgar in Chinese province of Xin Jiang to Gwadar in Balochistan gives it access towards the Gulf region.

The fact that we do not forget to lodge a protest whenever there is a move by China to undertake any project in the Pakistan occupied region of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir is laced with the irony that we failed to help those who were defending Skardu in semi starved condition and limited arms and ammunition. Timely defence of Skardu would have not only kept the region within the State but would have also been instrumental in regaining Gilgit after the perfidy of Gilgit Scouts under the British officers Major Brown and Captain Matheson.

Under their command the Gilgit Scouts carried out a coup de tat, taking the Dogra Governor as prisoner. After a brief and ineffectual resistance, the Governor was overpowered and on 3 November Major Brown ceremonially raised the Pakistani flag. Thus with Gilgit secured as a firm logistic link with Peshawar, the Pakistani backed and supported rebel forces of 2000 marched towards Skardu. Situated on the banks of Indus, the fort was defended by a garrison consisting of detachments from the 6 JAK. It was a mixed battalion consisting of Muslims and Sikhs and commanded by Lieut. Colonel Abdul Majid Khan. He was headquartered at Bunji. A detachment under Major Sher Jung Thapa was posted towards the east in Leh.

By now, depleted by defection and betrayal, and on the run in some places, the command of 6 JAK was handed over to Lieut. Colonel Sher Jung Thapa after promotion. With little threat at Leh because of its Buddhist population, he was asked to proceed to Skardu with all available force that could be spared. He reached Skardu on 3 December with a total strength of two officers, two JCOs and 75 other ranks of whom three were Muslims.

Even as Lieut. Colonel Sher Jung Thapa prepared a defence of the area, he requested reinforcements from Srinagar and also suggested that permission be granted to withdraw the garrison and civil administration to Kargil. Rejecting the suggestion, Srinagar ordered him to defend Skardu till ‘last man, last bullet’. By now, it need be remembered, the operational control of the State Forces was under the command of Indian Army which had already averted the threat to Srinagar and had begun to push the invaders back on the road to Muzaffarabad. Those taking decisions in Srinagar, however decided to send reinforcements under the command of Captain Prabhat Singh and Captain Ajit Singh. The first contingent was 90 strong and the second 70. It was minimally equipped and consisted of ‘orderlies, bandsmen and storemen’, as Major General D.K.Palit puts it. The first group began its 200 miles march after being dropped at Kangan on 13 January, 1948 and it made its way through snow, frostbite and damaged bridges to reach Skardu on the night of 10/11 February just in time for the assault launched by the enemy. The night also saw 31 Muslim other ranks and three wireless operators defecting from the fort. The second group arrived on 13 February, and a third, of equal number arrived on 15 February. In addition, there were more than 200 refugees in the fort who had to be fed from the meager resources at the command of the garrison.

Srinagar was not unaware of the difficulty but it still inexplicably depended upon whatever State Forces could be spared from other fronts for the rescue operation. Thus once again reinforcement was dispatched this time under Brig. Faqir Singh. This column crossed Zoji La in severe winter conditions and consisted of three platoons of infantry and was joined by another platoon of 6 JAK at Kargil. It was ten miles short of Skardu when it came under attack from the surrounding ridges. To cut the story short, it suffered heavy casualties and an injured Brig. Faqir Singh retreated to Kargil and from thence to Srinagar. It was then that the first personnel of the Indian Army, Major Coutts, but no troops, were attached to the column as Special Officer. More troops, this time from 7 JAK and 5 JAK were ordered to join Major Coutts as Biscuit Column and also, another officer of Indian Army, Lieut. Colonel Sampuran Bachan Singh joined the column. Soon, however, both the officers of Indian Army were recalled to their units. Thus, the Skardu garrison found itself in dire straits with more than 800 people to be fed from a ration for 80 and little hope of rescue.

Still optimistic, the garrison of Skardu waited for a miracle to happen. Instead more reverses were taking place. The troops between Zoji La, Kargil and Skardu were neutralized one after the other since the enemy had grown in strength, had control of vantage points and the local population too had opted to go with the tide. At Skardu, each enemy attack was eating into the manpower and ammunition of the defenders and each day into the rations. On May 12 Kargil had fallen to the enemy, and still there was no sign of the Indian Army making any move to help Skardu. It was then, on 16 May, 1948, that Srinagar ordered Lieut. Colonel Thapa to withdraw garrison and refugees to Olthing Thang. It was also ordered to carry maximum load of arms and ammunition. The gallant officer reminded that he had requested withdrawal when line of retreat was safe. Now that the countryside was totally under the control of enemy it was suicidal to retreat along with civilians, women and children, and stretcher cases. He, therefore, requested Srinagar to rescind order to withdraw and instead send help.

His request to rescind order was accepted but no help could be sent. A few sorties of air force did make ineffective attempts to air drop ammunition. Finally, with the last bullet exhausted, Lieut. Colonel Thapa sought permission to surrender. Ironically, it was 14 August and Pakistan was celebrating the first anniversary of its creation. Upon surrender, the enemy fell upon the surviving, killing men and raping women if not butchering them. Only Lieut. Colonel Thapa and his orderly survived and that because as a young hockey player in Dharamsala he was acquainted with a certain Captain Douglas Gracey, now Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army!

But those of us who are living, spare a thought for those who lived through a siege lasting more than six months, famished, hoping for the Indian Army to come and carrying out the order ‘last man, last bullet’! Let us not forget the sacrifice of those gallant men simply because they belonged to a State Force that was raised by those who were at loggerheads with the emerging powers of the times!

(The writer is author of ‘Maharaja Hari Singh : The Troubled years’)