MG NREGS (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Annual statistics

October-November 2016

The Times of India, Dec 13 2016

MGNREGA hires plummet by 23% in notebandi November

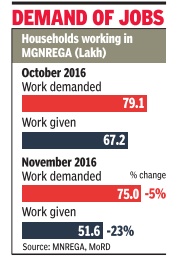

Subodh Varma The Modi government's demonetisation move seems to have taken the wind out of the sails of an already faltering job guarantee scheme. The number of households getting work in November dropped by 23% compared to the previous month and those being turned back empty-handed jumped to a staggering 23.4 lakh, almost twice the number in October.

Compared to the same month last year, work given this November is down by over 55%, indicating this is not a seasonal decline peculiar to November. With the overall emp loyment situation grim, this dip in jobs is expected to increase distress in rural areas. If there was work available (in MGNREGA), we would have got some relief at least. Now we get casual labour work at just Rs 50 per day , sometimes. Mostly we are just sitting, waiting,“ says Suniya Laguri, a 20-year old woman in Jharkhand's West Singhbhum district.

Suniya is voicing a concern that finds echoes across India in greater or lesser measure. Rural wages have crashed due to non-availability of cash as well as the desperation of the poorest -agricultural labourers and small or marginal farmers -to try and earn something in order to survive.

Mangoo Ram of Hardoi district in UP says his family survived the first few weeks by getting basic food items on credit and cutting down on an already minimal consumption. But now, in the fifth week of demonetisation, the situation is dire.

Most of the wages earned for work under the job guarantee scheme are deposited in banks or post offices. So, why has work itself suffered so much? The answer is not clear, with people citing different reasons. Shankar Singh of advocacy NGO Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan in Rajasthan says everybody -MGNREGA employees as well as people seeking work -were too preoccupied with standing at banks or post office lines for the first few weeks. This directly affected the whole system.

“Already , there was a squeeze on expenditure, with government not releasing adequate funds and gram panchayats overstretched. Notebandi has come on top of that, that is why this problem,“ Singh said.

Till December 12, gram panchayats were in the red to the tune of an incredible Rs 37,000 crore, according to the latest financial summary available with the rural development ministry .

That is, they had spent this much money but had yet to receive it from the top.

On the other hand, state governments had with them more than Rs 13,000 crore in funds that were yet to be transferred downwards.

There seems to be some efficiency issue also: in some states, work given under the scheme in November is not as bad as in others.

But the resultant ripples are evident all round.

The main issue is that banks are just not getting enough cash to dispense and people are waiting 4-5 hours to get Rs 200. Many return without any money .

With the reported return of thousands of migrants, the situation has worsened in rural areas as there is an army of unemployed in villages. Sowing for rabi (winter crop) is in progress but it cannot absorb everybody . This was the right time for the job guarantee scheme to open its doors wider and provide much needed relief. But that was not to be.

Fund allocation: 2013-16

Half of the fund allocation under job scheme MGNREGA goes to five states, but only two of them, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, rank high on the poverty list.

The paradox that poor states are not partaking of “distress labour“ scheme has been underlined by the Sumit Bose committee set up to analyse welfare schemes of the rural development ministry and suggest ways to prioritise beneficiaries.

A break-up of the fund flow under the job scheme between 2013-2016 shows that Andhra Pradesh (AP), Tamil Nadu (TN), UP, Bengal and Rajasthan have accounted for half of the allocations. AP, TN and Rajasthan are low on the list of deprivation or degree of poverty. In contrast, Bihar and Maharashtra are not among the top five states despite having “greater concentration of deprived households“, as mapped by rural household survey socio-economic caste census (SECC).

The expert panel's findings are in consonance with the general understanding that hard labour offered by MGNREGA should have greater demand from states with higher degree of poverty . The Bose panel has recommended that the scheme's focus should be more on poor regions.

Insiders acknowledge the paradox but attribute it to the nature of MGNREGA which is universal and demand-driven. Sources in rural development ministry said the scheme cannot be selectively focussed on poor states as it has to respond to demand whereever it emanates from. An earlier attempt to focus only on 2500 backward blocks kicked up a major controversy in 2015. However, a top official said the skewed relationship between poverty and work demand has been noticed and the ministry is building systems to help poor regions leverage MGNREGA better.Sources said instead of limiting the scheme to poor areas, the ministry has launched a concerted campaign to target families which have reported deprivation under SECC.

All gram panchayats have been asked to ensure that deprived households are issued “job cards“ so that they are encouraged to seek work.The campaign has a special focus on 2569 poorest blocks, as identified by the erstwhile plan panel. “The labour budget and employment has shot up in Rajasthan, UP , Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Assam, Odisha in 2016. We've tried to push up work there,“ he said.

Impact

Destroyed factory jobs, discouraged skill development

As Budget Day draws near, economic policy makers in the country are likely to shift their attention to the allocation of funds to various programmes planned for the upcoming year. Nrega is one such programme. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act aims to provide at least 100 days employment to the rural unemployed and underemployed by engaging them in rural infrastructure building.

While well-intentioned, our research based on careful study of employment and operating data from factories show that Nrega has led to some interesting consequences: factory jobs have declined by more than 10% and mechanisation has increased by 22.3% as a result of implementing Nrega.

It may have led to the migration of workers from higher value productive factory work to digging pits and filling them, with factories choosing to mechanise faster instead of replacing these workers. Nrega beneficiaries are required to exert some effort in order to earn a minimum wage. The purpose of such a requirement is to prevent those who are otherwise gainfully employed from crowding out these jobs and to ensure that only the truly unskilled and unemployed take up these jobs. Our research reveals that what transpired in practice was very different.

We looked into how implementing Nrega in a region adversely impacts the availability of labour for nearby factories, using factory-level data from the Annual Survey of Industries across the period 2002-10. Since our data includes time periods before and after Nrega was introduced, we are able to perform a pre-post analysis. Our results show that nearly 10% of the permanent factory workers jettison their factory jobs to join the Nrega bandwagon.

Why would a factory worker prefer 100 days a year of minimum wage Nrega work building rural infrastructure over an entire year's work at wages higher than minimum in a factory? We show that Nrega work is unlikely to involve a lot of effort. More importantly , workers may prefer the 100 days of guaranteed and effortless work near home to a high-effort high-risk factory job far from home. Having a job close to home also means less out-of-pocket expenses on travel, clothing and other requirements of factory work.

It is quite possible that such workers either work as contract workers in factories or do odd jobs in their villages during non-Nrega days. There was no decline in contract workers so it is plausible that the outflow of contract workers to Nrega was offset by erstwhile permanent workers turning into contract workers.

How did factories respond? Consider a factory whose cost of production is Rs 100 per unit if it employs workers and Rs 110 per unit if it employs machines to do a job. Naturally , the factory is likely to employ workers. Now if because of the availability of the Nrega option, workers demand Rs 120 per unit, the factory is likely to find using machines cheaper and let the workers go. This is indeed what we found.

Note that if the increase in wages is a result of increased productivity, per unit cost remains unchanged and hence factories are likely to continue employing workers as before.

Why is this migration of factory workers to Nrega undesirable? First, it defeats the very purpose of workfare, which is to prevent the already employed from cornering workfare jobs at the expense of truly unemployed. Second, this phenomenon negatively impacts both the Make in India and Skill Development programmes launched by the Centre. Factories that do not have access to ample financing to mechanise and cope with the labour shock engineered by Nrega may be forced out of business.

Third and most importantly , Nrega may be turning skilled factory workers into unskilled pit fillers (since Nrega discourages the use of machines of any form) while the really unskilled continue to be unemployed. Impact on skill development is severe and may have deeper consequences for human capital development in India as a country .

Our findings show that it is important to not just focus on allocation but also on programme design. From a societal point of view, there is a need to redesign Nrega to encourage skill development and discourage entry of gainfully employed productive workers. Imposing quantity and quality based output targets for the programme could be a first step in this direction.