Climate change: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

Climate change (issues)

Drought: caused by heavy Himalayan snowfall

‘Heavy Himalayan snowfall cause of drought in India’

Reading University Study Explains Reason For Poor Monsoon

Ashis Ray | TNN 2010

London: Reading University, one of UK’s leading research centres, claims to have solved a riddle that has perplexed scientists since the 19th century. An intensive study carried out by it has reached the conclusion that heavy snowfall over the Himalayas in winter and spring can be the direct cause of drought in India, especially in the early part of the summer monsoon.

Given that last winter was quite severe and mammoth quantities of snow may have fallen on the Himalayan range, all concerned in the Indian agrarian sector need to be vigilant about a delayed monsoon and plan accordingly. This is what the report appears to suggest.

Dr Andy Turner, lead author of the research at Walker Institute of the university, said: ‘‘Our work shows how, in the absence of a strong influence from the tropical Pacific, snow conditions over the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau could be used to help forecast seasonal monsoon rainfall for India, particularly over northern India during the onset month of June.’’

These findings are highly significant because Indian agriculture is heavily dependent on early rainfall; a lack of this in the crucial growing season tends to have a devastating impact on crops, as was experienced last year. The work is a part of Reading’s Climate Programme of the National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS).

Scientists have known since the 1880s that increased snow over the Himalayas can be linked with weaker summer monsoon rains in India. However, according to Reading, the mechanisms explaining this correlation have never been properly understood. The latest research shows that greater snowfall reflects more sunlight and produces a cooling over the Himalayas. This in turn means a weakening of the monsoon winds that bring rain to India.

The relationship is said to be strongest in the absence of warm (El Nino) or cold (La Nina) environments in the tropical Pacific, since these are normally the dominant control factors over the Indian rains. A spokesperson for Reading university said its research is based on extensive experiments with the British Met Office/Hadley Centre climate model.

2016: first normal rains since 2013

Amit Bhattacharya, Country gets first normal rains in 3 yrs, The Times of India Oct 2016

Overall Deficit Down By 11% Since Last Year

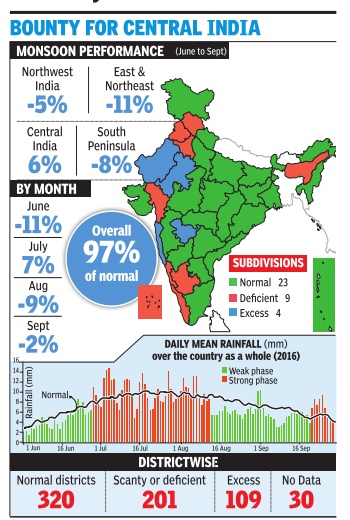

For the first time in three years, the country received normal rainfall in the monsoon season, which ended on Friday with an overall shortfall of 3% -within the normal range of +-4% but less than what the India Meteorological Department (IMD) had forecast.

Despite the IMD prediction of an “above normal“ monsoon not materialising, good rains in the crucial July-early August period boosted kharif sowing. Thereafter, bountiful showers in central India and Telangana also ended successive years of drought in these regions.

This was a welcome change from the drought years, when the deficit was 12% (2014) and 14% (2015).

The granary of the north -Punjab, Haryana and western UP -had to contend with another year of deficit rains. Punjab and Haryana ended with deficits of 28% and 27%, respectively , while western UP had a shortfall of 17%. Among the four regions, monsoon was above the long period average in just central India (+6%).

Of the 36 meteorological subdivisions, monsoon was excess or normal in 27 and deficient in nine. However, 201 districts (36%) recorded deficient monsoon .

Much of the shortfall can be traced to a period of low rain from August 10 to mid-Sep tember. “Conditions in the Indian Ocean became unfavourable around that time,“ said D Sivananda Pai, IMD's lead monsoon forecaster.

Warming

Nights getting warmer in India

Yields Of Rice, Other Cereals Could Be Hit

Amit Bhattacharya | TNN 2010

New Delhi: In an ominous sign of climate change hitting home, India has seen accelerated warming in the past few decades and the temperature-rise pattern is now increasingly in line with global warming trends. The most up-to-date study of temperatures in India, from 1901 to 2007, has found that while it’s getting warmer across regions and seasons, night temperatures have been rising significantly in almost all parts of the country.

The rise in night temperatures — 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade since 1970, according to the study — could have potentially adverse impact on yields of cereal crops like rice. The paper also finds that warming has been highest in post-monsoon and winter months (October to February).

‘‘Until the late 1980s, minimum (or night) temperatures were trendless in India. India was an odd dot in the global map as most regions worldwide were seeing a rise in night temperatures in sync with growing levels of greenhouse gases. Our analysis shows the global trend has caught up with India,’’ said K Krishna Kumar, senior scientist and programme manager at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, and one of the authors.

Regional factors seem to be getting over-ridden by warming caused by greenhouse gases. For instance, the cooling trend in much of north India seen in the 1950s and 60s has been reversed, possibly because the effect of aerosols in the air can no longer compensate for greenhouse gas warming.

Heat Is On

In last 100 yrs, mean temp has risen .82°C worldwide, and .51°C in India

However, India has seen sharp temp rise in recent decades. Since 1970, minimum temp up by .20°C/decade, faster than max temp (.17°C)

Western Himalayas warming up alarmingly at .46°C per decade

Across India, warming is sharpest during winter (.30°C per decade) and post-monsoon (.20°C) months Himalayan regions bear warming brunt

New Delhi: A study on temperatures has found evidence of accelerated warming in India. The study — Surface air temperature variability over India during 1901-2007 and its association with ENSO — by IITM scientists D R Kothawale and A A Munot besides Kumar, is a comprehensive analysis of temperature data gathered from 388 weather stations in the country and has been accepted for publication in the international Climate Research journal.

The rising night temperatures are a major cause of worry. Said Jagdish K Ladha, principal scientist in the India chapter of International Rice Research Institute, ‘‘Minimum temperatures have a link with rice fertility. At higher than normal night temperatures, rice grains aren’t properly filled up, leading to a drop in yield.’’

During 1901 to 2007, the all-India mean, maximum and minimum annual temperatures rose at the rate of 0.51, 0.71 and 0.27 degrees Celsius per 100 years, respectively.

However, post 1970, the rise has been sharper with mean and minimum temperatures both increasing at the rate of 0.2 degrees per decade, faster than the maximum temperature which rose by 0.17 degrees.

Among regions, the hardest hit seems to be the western Himalayas encompassing portions of Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. Here the mean temperature rise in the last century was 0.86 degrees while, more recently, temperatures have been going up by as much as 0.46 degrees per decade. The rapid warming of the region would have obvious fallouts on glacier melts.

On a seasonal scale, winter and post-monsoon temperatures show significant warming trends in recent decades though temperatures in other months have also been going up more modestly.

Rise in annual mean temperature: 1971-2013

9 Others Too Saw Similar Rise: Study

Delhi is among 10 major cities in the country , which includes all big metros, where the annual mean temperature has risen significantly higher than other cities over the last four decades.

A recent study by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) and the World Meteorological Organisation in Geneva, Switzerland, lists Delhi along with Kolkata, Jaipur, Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Nagpur, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai and Pune as cities with significant temperature rise from 1971-2013. The highest rise in mean temperature was in Jaipur (0.38°C), followed by Bengaluru (0.23°C) and Nagpur (0.21°C). Delhi is among four cities in the list which showed a decrease in mean annual temperatures from 1901 to 1970, before the trend got reversed.

This indicates increasing urbanisation has played a role in rising temperatures, said IITM's D R Kothawale, who headed the research. The other cities showing a similar trend are Ahmedabad, Jaipur and Hyderabad.

The study showed that even hill stations such as Srinagar, Shimla, Darjeeling and Kodaikanal had recorded a rise in temper atures over the last 40 years till 2013. The maximum and minimum temperatures in these hill stations had gone up by 0.4°C and 0.22°C per decade.

The researchers used seasonal and annual mean, maximum and minimum temperature data of 36 weather stations right from 1901.

Kothawale also said that the annual mean temperature of all the coastal stations showed a significant increasing trend.

Nine major cities -Kolkata, Jaipur, Ahmedabad, Surat, Mumbai, Pune, Nagpur, Bengaluru and Chennai -showed significant increasing trends in minimum temperature after 1971, whereas the maximum temperature during this period showed a significant increasing trend in six major cities -Jaipur, Mumbai, Nagpur, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai.

Heat index

Rising @ 0.56°C/ 0.32°C in summer/ monsoon per decade

Neha Madaan, Delhi hot, Mumbai hotter as heat index keeps surging, Feb 26 2017: The Times of India

Sees Decadal Rise At Rate Of 0.56°C In Summers

The average heat index in India is increasing significantly per decade at the rate of 0.56°C and 0.32°C in summer and monsoon respectively , a recent research by India Meteorological Department and Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology has found.

Heat index is a measure of the stress placed on humans by increased levels of temperature and moisture. The higher the heat index, the hotter the weather one feels, since sweat does not readily evaporate and cools the skin.

Of 25 mega cities analysed, 17, including Mumbai, Pune, Kolkata and Ahmedabad, have long-term average summer heat index in `very hot category'.

The study found that Mumbai and Pune from west India are in the `hot category' of the index in monsoon.Most mega cities in north India, including Delhi and Amritsar, are in hot category of the heat index during the summer season and in `very hot category' in monsoon.

`Very hot' category is considered dangerous, with health effects such as heat cramps, exhaustion and heatstroke with prolonged exposure or physical activity . The `hot category' requires peo ple exposed to it to take extreme caution.

The study found that 10 mega cities show significant increasing trends in monsoon heat index, including Mumbai and New Delhi.

“Most mega cities have significant increasing trends in summer and monsoon season heat index. Mega cities are densely packed with people, buildings, industries and motor vehicles. Heat released in the atmosphere gets trapped, meaning the ambi ent temperature is often higher than the immediate surroundings,“ said former IMD official and lead researcher A K Jaswal.

He said an interesting regional phenomenon is the stilling of winds. “Wind helps sweat to evaporate and the body to cool,“ he said. The study used monthly average maximum temperature and relative humidity records to analyse heat index during summer and monsoon from 1951to 2010 (60 years).

Glaciers, Himalayan

Shrinkage, 1962-2010

PTI

Himalayan glaciers shrank 16% in 50 yrs: Isro

Bangalore: Himalayan glaciers retreated by 16% in the last nearly five decades due to climate change, investigations by India’s scientists in selected basins in four states has revealed. The retreat of Himalayan glaciers and loss in a real extent were monitored in selected basins in J&K, Himachal Pradesh, Uttaranchal and Sikkim, under a programme on space-based global climate change observation by Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro).

“Investigations on glacial retreat were estimated for 1,317 glaciers in 10 sub-basins from 1962. This has shown an overall reduction in glacial area from 5,866 sqkm to 4,921 sqkm since 1962, showing an overall de-glaciation of 16%”, says the latest annual report of Isro. Snow cover monitoring of all basin has been completed, it said.

Atlases for three years are ready and one for the fourth year is being prepared. Modeling response of Himalayan cryosphere to climate change has been initiated, Isro added. Meanwhile, a study on the impact of temperature and carbon dioxide (CO ² ) rise on the productivity of the four major cereal food crops — wheat, rice, maize and pearl millet — revealed that yield of all of them showed reduction with increasing temperature.

Assessment after taking field data showed that wheat was the most sensitive crop and maize the least sensitive to temperature rise among the four, Isro pointed out. Another study for climate change impact on hydrology was carried out using “Curve Number” approach to study the change in run off pattern in India at basin level. “Analysis shows there will be significant increase of run off in the month of June in most of the major river basins”, the 2009-10 report of the Isro said. Isro has also observed a strong correlation between agriculture vegetation (mainly rice areas) and methane concentration.

Rate of retreat of Gangotri slows

The rate of retreat of Gangotri glacier has slowed down to 11 metres since 2008 from the maximum of 35 metres recorded in 1974, according to experts at the Almora-based GB Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment and Sustainable Development (GBPNIHESD) who conducted a study of the glacier located in Uttarkashi from 2008 till 2016. While this is good news, scientists said that the worrying part is that the base of the 30-km long glacier is thinning and has become more fragile.

Kireet Kumar, scientist at GBPNIHESD, who was involved in the study , told TOI, “We are not much concerned about the receding of the glacier since it is not so drastic. Our concern is more about the mass loss. Due to thin ning of its shape, Gangotri glacier has become vulnerable to fragmentation which would ultimately lead to breakage and loss of water.“

Farmer suicides, Naxal violence are a result

The Times of India, Dec 02 2015

Christian Parenti

Farmer suicides, Naxal violence linked to climate change

What if any connection is there be tween Naxalite violence and cli mate change? In 2009, I did re search in India to understand this question. At least one clear and disturbing pattern emerged: compare maps of precipitation with those of violence, and where drought advances, so do Maoists. This geography of linked ecological and socio military crisis runs down the Eastern Ghats, from Bihar and West Bengal, through Orissa and Chhattisgarh, into Andhra Pradesh and even further south and west.

This so-called “Red Cor ridor“ is also the drought cor ridor. During the years of the Naxal rise in Andhra Pradesh, drought was also intense: 19841985, 19861987, 19971998, 19992000, and 20022003 were all drought years.

But the Maoist fire burns not only due to drought; free-market government policies also fuel it.

In Telangana Jal, jungle, zameen, or “water, forest, land“ has been a rallying cry for local social organizations going back to the 1930s. It is a defense of the small farmer's place within the landscape, a defense of nature and the commons against all who would encroach.

In recent years it has also become a Naxalite battle cry. And now, as the extreme weather of anthropogenic climate change kicks in, jal, jungle, zameen takes on the qualities of a prophetic warning: we all depend on nature and we destroy it at our own peril.

There is a very strong scientific consensus on this: emissions from burning fossil fuels, primarily carbon dioxide, are trapping heat in earth's atmosphere and oceans that would otherwise radiate back out to space. This heating is disrupting the planet's climate system.

Worse yet, even if we drastically reduce emissions over the next several decades and thus manage to avert rapidly escalating self-compounding, so-called runaway climate change, civilization is still locked-in for major disruptions. Expansion of deserts, weakened monsoons, and a three-foot sea level rise, are, according to the scientists, pretty much guaranteed. In other words, even the best-case scenario is very bad.

Already climate change is happening faster than initially predicted, its incipient impacts are upon us all over the globe. India will not be spared in these upheavals. Climate scientists predict cataclysmic physical changes for the subcontinent in the near future.

Two-thirds of Indians are farmers. Most of them depend on Himalayan glacial runoff or the monsoon rains. Now both water sources are in danger due to global warming. The Himalayan ice pack is melting rapidly , while monsoon variability is increasing.

The summer monsoons account for fourfifths of India's total rainfall; the lighter, retreating or northwest monsoons deliver the rest. But things are less stable than in the past. Farmers in Telangana told me that recent years have seen only light winter rains. In many places that makes it impossible to plant a second crop. As the Pacific Ocean warms, the monsoon weakens further.

The US intelligence community is aware of all this and worried about it. “For India, our research indicates the practical effects of climate change will be manageable by New Delhi through 2030. Beyond 2030,“ said then US National Intelligence Director, Adm. Dennis C Blair during 2010 testimony to the US Congress, “India's ability to cope will be reduced by declining agricultural productivity , decreasing water supplies, and increasing pressures from cross border migration into the country .“

Most farmers in Telangana live by the mercy of the monsoons. Their agriculture has traditionally been dependent on water impoundment and storage.Canals feed out from the storage tanks, and elaborate social rules govern how and when water is allocated.

But water infrastructure requires public investment, and social solidarity , two things that are undermined by the individualism and money-first logic of free-market economic reform.

Starting in 1991 when the Indian government launched its first wave of economic liberalization, the state cut power subsidies to farmers. With that, running pumps for wells and irrigation became more expensive. To cope, farmers started taking loans, but for lack of a good local credit infrastructure they frequently turned to moneylenders.

At the same time in a pattern predicted by climate scientists drought became more frequent. To cope farmers had to spend more money to drill additional and deeper wells.

According to a World Bank study on drought and climate change in Andhra Pradesh: “Credit remains the most common coping response to drought.“ In fact, 68% of households in the study took loans due to drought. Large landholders borrow, “from formal sources (such as banks),“ explained the report, “while the landless and small farmers borrow from moneylenders at inflated interest rates.“

As the pattern of drought intensified so too did the burden of debt on the common farmer. Call it a downward drought-debt cycle. Another cause of debt is the costs of inputs, like seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers. The most demanding crop in this regard is cotton, particularly Monsanto's genetically modified Bt cotton.

According to the farmers, Bt cotton initially boosts yields and incomes, but after a few years, the soil is stripped of its nutrients and requires expensive fertilizers and pesticides. As the costs rise so too do the debts and Bt cotton becomes a curse.

Bizarrely , as the drought-debt cycle intensifies, cotton cultivation spreads and as it does the price falls. This combination of factors seemed totally nonsensical until a brilliant economic historian, Vamsi Vakulabharanam now a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, solved the puzzle.

The answer lies in the moneylenders. They demand cotton crops as collateral for their loans because cotton is inedible. Thus, during times of crisis an indebted farmer cannot “steal“ that is eat the collateral. Even when food crops, like grains, command higher prices, the moneylenders will not advance credit for such crops because those crops carry greater risks. Cotton is the moneylenders' biological insurance.

Thus, many Telangana farmers are trapped in a downward economic cycle: they need credit to get the expensive inputs needed to produce cotton, but the more cotton they produce the lower its price, the lower the price of cotton the more they must plant borrowing to do so, and falling ever deeper into debt.

The shift to cotton has coincided with the government's move towards neoliberalism and away from the various legal protections and government subsidies for poor farmers like public credit and public investment in irrigation.

If government-subsidized credit schemes were available, many of these Telangana farmers would not rely on moneylenders and thus would not over-plant cotton.

All these factors -government abandonment of the poor, predatory private credit markets, and due to climate change an increasingly hostile environment -combine to fuel desperation.

Suicide, for many , is the only escape. Often the preferred method, as if victims were attempting to illustrate some larger political point, is swallowing pesticides. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 150,000 Indian farmers killed themselves between 1997 and 2005. In Andhra Pradesh, an esti mated 2,000 to 3,000 farmers killed themselves between 1998 and 2004.

The same desperation that drives suicide also drives political homicide; which is to say, Naxalite violence.

For years, the police special forces, have conducted search-and-destroy operations in the forest belt of northern Telangana.

Such counter-insurgency strategies create high profile human rights abuses. But they also damage the social fabric by sowing suspicion and alienation. This hidden social damage promises future problems because adaptation to climate change will require deeper solidarity and more cooperation, not less.

Naxalite violence is not the only flashpoint on the spectrum of existing and possible climate violence. Climate change will force millions of people to relocate. Currently there are an estimated 60 million refugees worldwide and already we feel the strain, just look at Europe. However, a major study from Columbia University projects that by 2050 fully 700 million climate refugees will be on the move.

Increasingly , the response to migration is border militarization. Be it in the United States, or Europe, or on India's frontier with Bangladesh, the pattern is the same: barbed wire, armed guards, aerial surveillance. These responses to mass migration play well with panicked electorates but they do not offer long-term solutions.

Avoiding a nightmare version of the future requires mitigation, cutting greenhouse gas emissions, switching from fossil fuels to clean energy. But it also requires humane and just forms of adaptation.

How should India prepare for massive internal and international dislocation and migration? By charting a path toward a clean energy future and just climate adaptation based on economic redistribution, social justice, and sustainable development.This alternative path forward is often dismissed as utopian but it is actually far more realistic and sustainable than the alternative, which is a future of endless counter-insurgency , ever more militarized borders, and a steady erosion of democracy .