K. Subrahmanyam, filmmaker

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A brief biography

S. VISWANATHAN | A progressive film-maker | Frontline

K. Subrahmanyam was perhaps the first Tamil film-maker to challenge religious orthodoxy and fight social maladies through cinema.

Since its inception, Tamil cinema has had close links with politics - of the ruling class, of gods and goddesses, of kings and queens, and of the national and Dravidian movements. So, when Tamil cinema began to speak in 1936, it spoke mostly politics. The formative years of the film industry (1936-1946) in Tamil Nadu were also a crucial period in the history of the struggle for Independence, when the Congress was attempting to enlarge the mass base of the movement.

During this period, thanks to the solid base built by a popular stage with the active participation of patriotic artists and the entry of some committed intellectuals who explored the potential of cinema as an instrument of change, Tamil cinema played a significant role in mobilising support for the freedom movement, particularly among the unlettered and under-privileged sections.

Film director and producer K. Subrahmanyam was one such committed intellectual who was keen to make films that were artistic and purposeful. Apart from enlisting support for the freedom movement, his films sought to make people aware of a host of social issues crying for solution, such as the near-enslavement of women, child marriage, the dowry system, the ill-treatment of widows, and untouchability. Thus, Subrahmanyam helped the national movement move towards its climax with a larger mass participation and sowed the seeds of social reform, paving the way for the Dravidian Movement to play its role in post-Independence cinema.

Those who know his works recall his contribution in enriching Tamil cinema by making purposeful films with high professional skill and mobilising support for the cause of political independence, social reforms and a cultural renaissance.

Prominent among the 20-odd films he produced during nearly two decades of active life in the film world are Bala Yogini (1936), Seva Sadhanam (1938), Thyaga Bhoomi (1939) and Bhakta Chetha (1940). Besides holding aloft the banner of Independence, his films highlighted the social ills that slackened the progress of the Tamil people.

Subrahmanyam introduced a number of artists to a career in films, foremost among them being the Carnatic music stalwart M.S. Subbulakshmi. Others include the eminent actor-singer M.K. Thiagaraja Bhagavathar, S.D. Subbulakshmi, music composer Papanasam Sivan, `Baby' Saroja (a niece of Subrahmanyam), the Bharatanatyam trio Lalita, Padmini and Ragini, B. Saroja Devi and K.J. Mahadevan. Another music exponent of the period, D.K. Pattammal, was introduced as a playback singer in Thyaga Bhoomi. Subrahmanyam's wife Meenakshi, who wrote and composed songs for his films, was perhaps Tamil cinema's first woman lyricist and music director. He introduced his daughter Padma Subrahmanyam as a dancer in the film Gita Gandhi.

An institution-builder, Subrahmanyam was instrumental in founding many professional bodies such as the South Indian Film Chamber of Commerce, the South Indian Film Artistes Association, the Film Institute, and the Nadaswaram Artists Association. After he stopped producing films, he worked for the welfare of film artistes. He visited several nations, including the United States and the erstwhile Soviet Union, as member of cultural delegations. He arranged for the visits of many foreign film personalities and facilitated their interaction with Tamil artists. His progressive mind and humanitarian outlook made him a close friend of Marxist leaders such as V.P. Chintan and P. Jeevanandam. He also served as the president of the Indo-Soviet Cultural Society.

Early life

BORN into an orthodox Brahmin family based in Kumbakonam on April 20, 1904, Subrahmanyam studied law. He left the Bar after a brief stint to enter the film field. He joined Associate Films, Chennai, in 1928 during the era of silent films and made a few films such as Anathai Pen (1931) on contemporary themes. After a short break during which he served as a member of the Scout Movement, he returned to the film industry in 1934. Convinced of the rich potential of cinema, he started making films under the banner of his own business unit, Madras United Artistes Corporation.

Why did Subrahmanyam choose to expose social maladies instead of making films based on mythology unlike the rest of his clan?

Although a believer, he did not approve of many social practices that were ritually sanctioned by religion. One possible explanation for this unorthodox mindset is given by the film historian S. Theodore Baskaran in his book The Message Bearers (Cre-A, 1981). Based on an interview with Subrahmanyam's son S. Krishnaswamy, he writes: "His (Subrahmanyam's) father C.S. Krishnaswamy Ayyer was a lawyer handling the cases of big mutts around Kumbakonam. He would often feel guilty about being a party to the injustices perpetrated by the mutts in the name of religion and deplored that the priesthood was not playing the positive role it should in society. Subrahmanyam imbibed all these ideas from his father, and his highly critical view of the priesthood was reflected in all his films, particularly in Bala Yogini, in which he treated priests with ridicule and even used scenes showing priests for comic relief." In fact, Subrahmanyam's interest in art and culture seems to have been the result of the influence of his father, who was an amateur stage actor, deeply interested in Shakespearean plays. The political and social conditions of the period were also ideal for Subrahmanyam to venture into the field with progressive ideals.

Nationalism

THE 30 years that followed the birth of cinema in southern India in 1916 constitute one of the most eventful periods in the political, social and cultural history of Tamil Nadu. After nearly two decades of silent films, Tamil talkie emerged in 1936. The evolution of cinema into a mass entertainer coincided with the growth of the Indian National Congress, which spearheaded the freedom struggle, into a mass movement. The Jallianwallah Bagh massacre (1919) shocked the nation and the protest against British Raj spread to different regions. The Congress had by then come under the leadership of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Gandhi's policy of using non-violence and passive resistance to bring about political and social changes had won him public acclaim. He launched the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921 and the Civil Disobedience Movement and the Salt Satyagraha 10 years later as part of the struggle for Independence. These agitations received tremendous response from people across the country and thousands were imprisoned. The Government of India Act, 1935 provided for political rights to people at the provincial level. The formation of Congress governments in many provinces, including Madras, following elections to State Assemblies helped reduce the rigours of alien rule that were until then experienced in various fields, including the film industry. It gave people hope that the Congress governments in the Provinces would implement many of Gandhi's declared ideals and reformist policies to help build unity among the people fighting for liberation.

Alongside the nationalist movement, there was the growth of the Self-Respect Movement led by the iconoclast Periyar E.V. Ramasami, which would evolve into the Dravidian Movement. Periyar's movement stood for social equality, annihilation of caste-related discriminations and an end to irrational beliefs. Gandhian ideals and rationalist thought spread among the people. During the same period the kisan movement began to take root in rural Tamil Nadu. Struggles by agricultural workers in Thanjavur district under the leadership of the Communist Party highlighted the social and economic disabilities of these people, the majority of whom were Dalits. The active presence of these socio-political movements provided a fertile ground for political cinema to make its appearance. "At the time of the appearance of the Tamil talkie," observes Theodore Baskaran in The Message Bearers, "the political atmosphere in Madras (Province) was such that no performing art as mass-based as the cinema could remain unaffected by it for long." He further writes: "Stimulated by the political fervour of the day, Tamil cinema gained a new content and course. The challenge of foreign rule and the awareness of the need for social reforms as a part of the society's efforts to meet this challenge profoundly affected Tamil cinema. As the mass basis for the demand for freedom widened and the people began participating in elections, film-makers responded increasingly to the political tensions of the times by mirroring this mood."

The presence of a political theatre prior to the advent of the cinema, whose performers were dedicated patriots, and the patronage that Congress leaders such as S. Sathyamurthy extended to the two art forms, cinema and drama, with a view to using cinema to mobilise support for the freedom movement encouraged the production of films on patriotic themes. Tamil cinema and the freedom movement became increasingly dependent on each other. At least a few producers seized the opportunity, Subrahmanyam being a notable example.

Although the political atmosphere inspired film-makers to produce films on national movements, the colonial government's attitude to such films was understandably unfriendly. As the censorship rules were rigid, most film-makers chose the easier option of producing films centred on romance or mythology. However, Subrahmanyam was keen to produce offbeat films, while making a few commercials to stay in the industry.

Bala Yogini was a bold attempt to portray the pathetic condition of widows in orthodox middle-class Brahmin families of the time. "The film attacked the caste system, exposed the hypocrisy in the priesthood and pleaded for better treatment of widows. There was a sequence showing a Brahmin widow and her little daughter taking shelter in the household of a low-caste servant who offered to take care of them," writes Theodore Baskaran. The splendid performance of Baby Saroja was a special feature of the film.

Recalling his impressions of the film, octogenarian Marxist leader N. Sankaraiah says, "I saw Bala Yogini when I was a schoolboy. The film made a deep impression on me. It touched an important social issue concerning middle-class Brahmin families of those days - ill-treatment of widows. The film was really a bold attempt. A widow lived a life of terrible agony. In those days, one could see in every Brahmin family at least one young widow. It was mostly because of the prevalence of child marriage. Marriages were made at a very young age resulting in many young girls becoming widows. When these girls had no option other than living in their parents' places, they were considered a burden on their fathers and brothers. Their health and well-being came last in the family's priorities. Director Subrahmanyam through this brave venture succeeded in creating public awareness about the problem."

Bhaktha Chetha focussed on caste-based segregation of a significant section of society, which was categorised as "outcastes" and "untouchables". It told the story of a cobbler winning God's favours through his devotion. The story was based on an episode from the Mahabharata. Yet it was unacceptable to religious die-hards. Two orthodox Sanatanists of Madurai took the issue to court. They prayed that the film be banned on the grounds that it was a misrepresentation of Hindu dharma and the orthodox Sanatana movement and that it would influence the politics of temple entry in Madurai. (The reference here is to the movement led by veteran freedom fighter and Congress legislator of Madurai A. Vaidyanatha Iyer to take Dalits, then known as Harijans, into temples, where certain sections of society, particularly the "untouchables," were refused entry.) Bhaktha Chetha sought to create awareness among the people about the movement for the eradication of untouchability launched by Mahatma Gandhi.

Seva Sadhanam championed the cause of women's equality. Based on a novel by Premchand, the film was a bitter attack on the dowry system, which often compels poor young girls to marry men much older to them. The film forcefully discussed the havoc caused by the incompatibility between such couples and sympathised with the victims. Subrahmanyam introduced M.S. Subbulakshmi as an actress in the film, which was a big success. Tamil film critic and historian Aranthai Narayanan observes in his book Thamizh Cinemavin Kathai (The Story of Tamil Cinema) that Seva Sadhanam proved a turning point in the history of Tamil cinema. In the climax, the aged husband, now a totally changed man, was shown as casting aside with utter contempt his `sacred thread', which symbolises his Brahmin superiority. It came as a stunning blow to the orthodoxy, the critic writes. The author admires the high professionalism of the director in choosing a real-life widow, with a shaven head and a white saree, to play the role of a widow.

Describing Seva Sadhanam as an "unusual film" on the age-old practice of old men marrying young girls as their second wives, "sanctioned by customs and religions in a male-dominated society, Sankaraiah says the film was highly successful in bringing out the sufferings of the girl and the mental agony of the aged husband. F.G. Natesa Iyer's performance in the role of the old man was impressive, Sankaraiah says.

However, it is Thyaga Bhoomi that remains the most acclaimed of Subrahmanyam's films. It is based on a story written by the novelist Kalki R. Krishnamurthy ("Renaissance Man", Frontline, October 22, 1999), which was serialised by a Tamil weekly during the making of the film. The magazine used stills from the scenes shot every week as illustration for the story.

The film, which had the Salt Satyagraha as its backdrop, focussed on women's rights and untouchability. It tells the story of the daughter of a poor Brahmin priest. Discarded by a rich and Westernised husband, the girl returns to her village. Unable to find her father, who had by then been banished from the village for throwing open the temple to Dalits who were victims of a cyclone, the girl migrates to a city. When she becomes rich, her former husband comes back to her but she rejects him. The husband moves the court to get his matrimonial rights restored, but the girl tells the court that she would rather pay alimony than be reunited with him. She dedicates herself to the cause of the nation by joining the freedom movement - an idea that was considered revolutionary even for the times. The film, which received tremendous response, was banned not because it propagated revolutionary ideals, but because it contained scenes relating to the freedom struggle. It showed a large number of women, including the heroine, being arrested, when they went in a procession. "It was the first time that women's participation in the freedom struggle in such large numbers was shown in a film and it inspired women everywhere," Sankaraiah says.

Speaking of the overall impact of Subrahmanyam's films on society, L. Ilayaperumal, veteran freedom fighter, Dalit leader and former Member of Parliament, says that their message was received well and it helped mobilise support for the freedom movement in a big way. Dalits were happy that the films highlighted their sufferings "with the good intention" of eradicating untouchability. "We welcomed such films because they were doing the maximum they could at that point of time to bring awareness among the people about the atrocities against Dalits," Ilayaperumal says.

Recalling his impressions of Subrahmanyam's films, writer and journalist P. G. Sundararajan (Chitti), who turned 95 this May, says, "He was perhaps the first film-maker to make films on serious social problems without, at the same time, ignoring the entertainment aspect. What the stories and novels of eminent men of the Manikkodi group of writers, such as Va. Ra., and novelists such as Vai. Mu. Kothainayagi, could not achieve was made possible by these films. That is, the creation of awareness."

Why should such a brilliant film-maker downsize his operations after Independence? He made very few films between 1940 and 1971 when he passed away. "Father made handsome profits at the box office but lost it all owing to post-War economic changes. By the mid-1950s, films could no longer be made without black money, the handling of which was unthinkable for a genuine Gandhian. My father gave up film-making and remained a social activist," says son Krishnaswamy.

Critiquing caste, reversing the hierarchy

Gopalan Ravindran |‘Caste in Film’| August 5, 2015 | Indian Express wrote:

It began in the 1930s, with early Tamil pioneer K. Subramaniyam, a Brahmin, who sought to locate characters in the binary social divide between Brahmins and the “untouchables” in films such as Nandanar (1935). In this film, the Brahmin character, played by Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer, falls at the feet of the Nandanar, from an “untouchable” community, played by legendary female singer and actor K.B. Sundarambal, belonging to a “caste Hindu” community. It drew protests from Brahmins in places like Kumbakonam and there are references to the social boycott of Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer in Kumbakonam for the “sacrilegious act of falling at the feet of an ‘untouchable’”.

Filmography

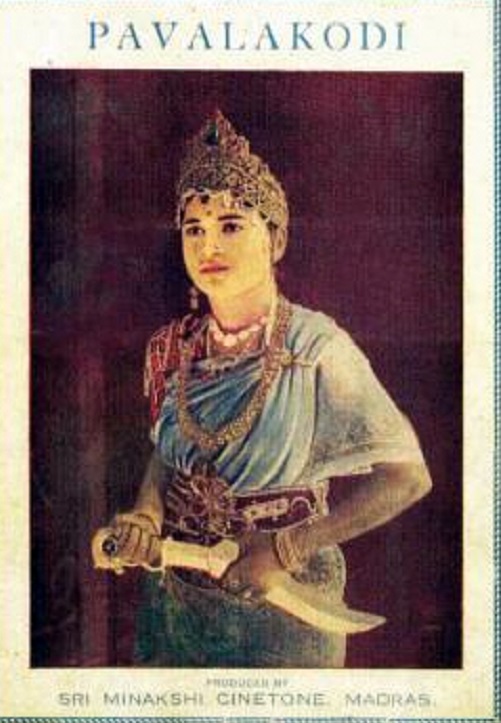

Pavalakkodi (1934)

Naveena Sadaram (1935)

Balayogini (1937)

Sevasadanam (1938)

Thyagabhoomi (1939)

Bhaktha Chetha (1940)

Prahlada (1941) (Malayalam)

Ananthasayanam (1942)

Bharthruhari (1944)

Maanasamrakshanam (1945)

Vikatayogi (1946)

Vichitra Vanitha (1947)

Gokuladasi (1948)

Geetha Gandhi (1949)