Women’s employment: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

Women's employment

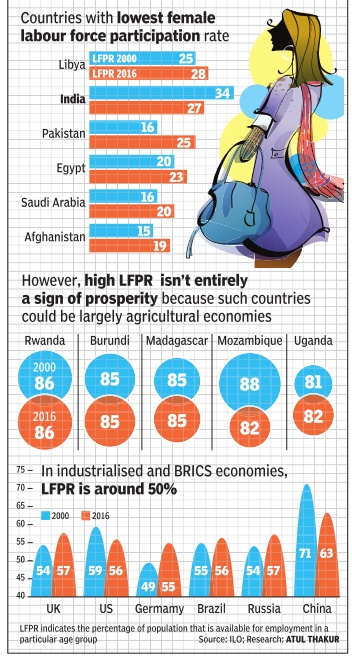

2000-16: Female Labour Force Participation rate, India and the world

See graphic

2005-12: Employment level, women

The Indian Express , July 26, 2016

Since 2005, fewer jobs for women in India

In rural areas, female labour force participation among women aged 15 years and above has fallen from 49% in 2005 to 36% in 2012. More than half of the decline is due to the scarcity of suitable jobs at the local level.

Female labour force participation in India is among the lowest in the world. What’s worse, the share of working women in India is declining. This is a cause for concern since higher labour earnings are the primary driver of poverty reduction. It is often argued that declining female participation is due to rising incomes that allow more women to stay at home. The evidence, however, shows that after farming jobs collapsed post 2005, alternative jobs considered suitable for women failed to replace them.

Rising labour earnings have been the main force behind India’s remarkable decline in poverty. The gains arise partly from the demographic transition, which increases the share of working members in the average family. But trends in female labour force participation veer in the opposite direction. Today, India has one of the lowest female participation rates in the world, ranking 120th among the 131 countries for which data are available. Even among countries with similar income levels, India is at the bottom, together with Yemen, Pakistan and Egypt (Figure 1). Worse still, the rate has been declining since 2005. This is a matter of concern as women’s paid employment is known to increase their ability to influence decision-making within the household, and empower them more broadly in society as a whole.

This declining trend has been particularly pronounced in rural areas, where female labour force participation among women aged 15 years and above fell from 49% in 2005 to 36% in 2012. This is the most recent period for which data are available. The numbers are based on the National Sample Survey’s (NSS) definition of ‘usual status’ of work, but the trend remains similar with other definitions too. In a recent paper, we argue that the explanation for this disturbing trend is the lack of suitable job opportunities for women. In a traditional society like India, where women bear the bulk of the responsibility for domestic chores and child care, their work outside the home is acceptable if it takes place in an environment that is perceived as safe, and allows the flexibility of multi-tasking. Indeed, three-quarters of women who were willing to work, if work was made available, favoured part-time salaried jobs. From this perspective, female labour force participation can be expected to depend on the availability of ‘suitable jobs’ such as farming, which are both flexible and close to home. However, the number of farming jobs has been shrinking, without a commensurate increase in other employment opportunities. Our research suggests that more than half of the decline in female labour force participation is due to the scarcity of suitable jobs at the local level.

A large body of academic work in India has focused on a different explanation, the so-called “income effect”. It is argued that higher household incomes have gradually allowed more rural women to stay at home, and that this is a preferred household choice in a predominantly patriarchal society. Other frequently-mentioned explanations are that the share of working women is declining because girls are staying longer in school. It is also said that with shrinking family sizes, and without the back-up of institutional child support, women have no option but to stay out of the work force. We are sceptical. Staying longer in school and being less able to rely on family support for child-rearing could justify a decline in participation rates among younger women, but not the equally important drop among middle-aged cohorts. There are also reasons to downplay the income effect. Between 2005 and 2012 India experienced roughly a doubling of wages in real terms. But across districts, a doubling of real wages is associated with a 3 percentage point decline in female participation rates, not with the much larger 13 percentage point fall that actually occurred. Our research shows that these factors explain less than a quarter of the recent decline in India’s female labour force participation.

Evidence also points to a less ‘voluntary’ withdrawal of women from the labour force than the income effect explanation implies. The NSS, which is the main source of labour market data, tends to underestimate women’s work. What most working women do in India does not match the image of a regular, salaried, 9-to-5 job. Many women have marginal jobs or are engaged in multiple activities, including home production, which is often hard to measure well. Female unemployment may be underestimated as well. If one were to relax the stringent criteria used by the NSS to define labour force participation, and include the women who participated under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), or were registered with a placement agency, then the female labour force participation rate would be between 3 and 5 percentage points higher. This measurement problem is further evidenced by the population census data that report much higher rates of female unemployment than the NSS. Beyond the income effect and measurement issues, the main driver of the decline in female labour force participation rates is the transformation of job opportunities at the local level. After 2005, farming jobs collapsed, especially in small villages, and alternative job opportunities considered suitable for women failed to replace them. Regular, non-farm employment only expanded in large cities (Figure 2). As a result, there is a ‘valley’ of suitable jobs along the rural-urban gradation. Fortunately, the decline in female labour force participation is not irreversible. The trend can be turned around through a more vibrant creation of local salaried jobs — including part-time jobs — in the intermediate range of the rural-urban gradation where an increasingly large share of the Indian population now resides.

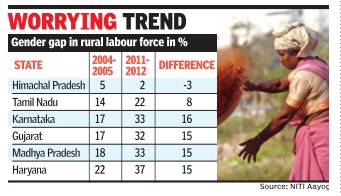

2004-2012:Women as rural labour

The Times of India Jan 11 2016

B Sivakumar

Chennai Women in rural areas are increasingly withdrawing from the country's labour force. This trend is particularly evident in states like Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh where women have opted out of the labour force over the years. It is also quite strong in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where the difference in gender gap between 2004 and 2011 is 8%. In Karnataka, it is 16, while in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh it is 15. The higher the gender gap the lower the female participation in labour force.

According to a study conducted by Niti Aayog, the main reasons are lack of job opportunities for women in rural areas and the poor performance in the agriculture sector. Due to the fall in number of women in the labour force, the gender gap has increased to 25 percentage points in India between 2005 and 2011.

“Women who lost jobs in agriculture did not find place in other sectors of the economy . One of the reasons is the poor education of rural women that acts as a barrier to a smooth inter-sectoral labour mobility . Nearly 69% of rural women are either illiterate or have been educated only up to the primary level,“ said the study done by Sunita Sanghi, A Srija and Shirke Shrinivas Vijay of NitiAayog.

“While there is a rise in real wages of women labour force after introduction of MGNREGS, younger women in the school and college going ages are migrating to towns for education. It is only the older women, who have lost employment opportunities,“ said said Madras Institute of Development Studies professor D Jayaraj.

2009-12

Rural women lost 9.1m jobs in 2 yrs, urban gained 3.5m

Not Getting Long-Term Work: Survey

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

Women’s employment has taken an alarming dip in rural areas in the past two years, a government survey has revealed. In jobs that are done for ‘the major part of the year’, a staggering 9.1 million jobs were lost by rural women. In urban areas, the situation was quite the reverse, with over 3.5 million women added to the workforce.

This emerges from comparing employment data of two consecutive surveys conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) in 2009-10 and 2011-12. Key results of the later survey were released last month. Both rounds had a large sample size of nearly 4.5 lakh people.

“The survey shows that in the continuing employment crunch in rural areas, the most vulnerable sections — like the women — are getting eliminated,” says Amitabh Kundu, professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

If subsidiary work, that is short-term, supplementary work is also counted, women’s employment numbers improve, but they still show a huge decline of 2.7 million in two years. This is a reflection of the fact that women are no longer getting longer-term, or principal, and better paying jobs, and so are forced to take up short-term transient work.

Declining women’s employment in rural areas is a long-term trend in India despite high economic “growth”, says Neetha N of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies.

“Three decades ago, in 1983, about 34% of women in rural areas were working. This has steadily declined and now stands at just short of 25%. But the decline in the past two years is shocking – it is the most drastic decline we have ever seen,” she says.

Low investment in agriculture

‘Poor investment in agriculture behind rural job dip’

Many argue that decline in women’s work is taking place because more women are now either studying or just staying home because the men of the family are earning enough. However,this is not supported by the data, according to Neetha. “Urban areas have more girls’ enrolment in schools and colleges, and better household incomes than rural areas. Yet women’s employment is increasing in urban areas and declining in rural areas,” she points out.

But what is the reason behind this jobs crisis in rural India? “A decline in public investment in agriculture, and in extension work for dissemination of knowledge coupled with increasing mechanization are the main causes of this crisis of jobs,” says V K Ramachandran, professor of economic analysis at the Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore. He also blames the severe slowdown in expansion of irrigation and supply of electricity to rural areas for causing jobs to dry up.

Satya Narain Singh, deputy director general of NSSO, told TOI that there were no issues of measurement or sample size in the surveys. He pointed out that the population for 2010 was based on Census projections while that for 2012 was based on actual Census 2011 data. This could introduce a small over-estimation of the 2010 population. But the “decline in female workforce is in line with the trend of decline observed in recent decades”, Singh said.

2015-16

Kerala

The Times of India, May 09 2016

Subodh Varma Of the nearly 25,000 person days of work done under the job guarantee scheme (MNREGA) in Kannapuram gram panchayat in district Kannur, 97% was by women. This seems some kind of a record but Kerala has many such villages -91% work done in 201516 under the jobs scheme was by women.

More than good implementation it's a result of the dismal employment situation in a state repeatedly ranked number one on human development and gender empowerment indices.

The last NSSO employment survey showed the share of working women in women's population was just about 22% in rural areas and 19% in urban ones -almost as poor as the low levels in most north Indian states and unlike any “gender empowered“ state.

In Tamil Nadu, with similar levels of urbanisation and literacy, women's work participation rate is about 38% in rural areas and 20% in urban areas.

Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the country saw a steep fall in women's employment with work participation plummeting by 32% in rural areas and 11% in urban areas. TN, with its mix of industrial and agricultural production, saw a fall in women working by about 18%.

In Kerala, with agriculture declining and scanty industrialisation, the effect of the workforce's de-feminisation was less calamitous though as painful.

“Women have been pushed into work like teaching in schools where their share is about 70%. Farmwork, the main source of women's employment, has declined. No alternative has emerged,“ says Neetha P of the Centre for Women's Development Studies.

Men's work too has declined but they have seized the oppor tunity to migrate abroad, espe cially to the Gulf.

This prevented a financial collapse of millions of families -one estimate put the total number of Keralites who've ever worked abroad at 3.6 million. Some 1.1 million Keralites also migrated to other states.

Strangely, Kerala is also home to about 2.5 million inmigrants, mostly from Bengal and Odisha. They work as labour in construction and hotels, says Neetha. “Keralites consider it below dignity to work in such positions. Poorer people from other states moved in,“ she added.

Attrition

Weaker sections hold on to jobs

Namrata Singh, `Women from weaker sections hold on to jobs', March 8, 2017: The Times of India

Corporate Exposure, Role Models, Mentoring Go Long Way In Tapping Potential, Says Study

Women's attrition remains a big challenge for companies. Tapping into the vast potential of women from underprivileged sections of society could provide the requisite solution through simple methods of creating career intentional initiatives.

Corporate exposure, role models and mentors have emerged as a key vector of career intentionality creators that upgrade women from underprivileged backgrounds, in their careers, according to Avtar Group's career intentionality report, shared exclusively with TOI.These, along with career intentionality sustainers (family support, scholarship, motivation net, additional coaching and infrastructural support) and career intentionality propellers (such as intrinsic skills like determination, focus, hard-work and ambition), form a career development model that has helped women in their socio-economic development (see graph).

The study was conducted between September 2016 and January 2017 and covers 1,488 subjects, who had spent over eight years working for the same organisation at an early career stage. Of these, 34% -or 496 women -came from underprivileged backgrounds and had studied in corpora tiongovernment schools.

Saundarya Rajesh, founderpresident, Avtar Group, said, “This study , which was constructed upon identifying a trend of low attrition associated with women employees from humble backgrounds, revealed that when a girl from an underprivileged family obtains a role model or a mentor who intervenes at critical junctures in her life, she becomes `career-intentional' and, in eight out of 10 cases, is able to complete tertiary education that leads her to a higherpaying job, as compared to what she would have earned as a domestic servant. This presents a unique opportunity for corpora te India to build a new cadre of gender-diverse talent, which has potential to buck the trend of high women's attrition.“

Pratap G, senior director (HR), Maersk Global Services Centre, said, “The deceptive myth of what a `leader looks like' can hinder women from getting into senior leadership position.“ At Asian Paints, mentoring, coaching, job rotationexposure and leadership development are gender-neutral interventions. Emrana Sheikh, VP (HR), Asian Paints, said, “Every drop adds to creating the ocean and, hence, every woman leader that emerges in the organisation sows the inspiration for many others as a role model.“

Gender pay gap

2016: 27%

The Times of India, May 18 2016

Gender pay gap high at 27% in India

The gender pay gap in India stands at 27%, according to the latest Monster's Salary Index (MSI). According to the report, women earned a median gross hourly salary of Rs 207.9 against Rs 288.7 for men. The highest gender pay gap was recorded in the manufactu was recorded in the manufacturing sector at 34.9%, where there are strict regulations with respect to women working in factories. On the other hand, the lowest gender pay gap was recorded in the BFSI and transport, logistics and communication sectors at 17.7%. These sectors see greater participation of women in the workforce.

At a gender pay gap of 27%, India does not fare well compared to other countries. While Monster did not reveal comparative global numbers, other reports have ranked India high among countries (Japan, Ko rea) with a gender pay gap above 25%. In most countries, including the US, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, France Germany and Mexico, the gender pay gap is below 20%. In New Zealand and Spain, it's below 10%. According to reports citing World Bank statistics, on an average, for every $100 earned by a man, a woman was paid around $76.

Reasons attributed by Monster for the gender pay gap in India include a possible preferential treatment towards male employees for promotions to supervisory positions and career breaks taken by women due to parenthood and other socio-cultural factors.

Sanjay Modi, MD (India Middle EastSoutheast Asia Hong Kong), Monster, said, “Worldwide, the lack of pay parity has taken a centre stage with strong views being shared by sportspersons, political and business leaders alike. Men often receive higher salary offers than women vying for the same title in the same organization. Needless to say, the situation is far from desired in India, especially when the country is gearing towards inclusive development.“

Modi said while some cri tics may claim that this gender pay gap is simply due to the choices women make, occupation, family, or education level, “that could not be further from the truth“. “ There is a strong need to create equal opportunities for all, particularly women, who are key contributors in the Indian job market,“ said Modi.

Salary/ wages

2016: Women earned 25% less than men

Women earn 25% less than men in '16: Study , March 7, 2017: The Times of India

Mfg, IT, Fin Top Sectors In Pay Difference

The average gender pay gap in India may have narrowed by two percentage points since last year, but it still stands at a yawning 25%. According to Monster Salary Index (MSI) data from 2016, men earned a median gross hourly salary of Rs 346, while women earned only Rs 260 in 2016. While it is an improvement over last year's over 27%, the pay gap is a notch higher than 24% in 2014. In the manufacturing sector, the average gender pay gap is as high as 30%, even though this is an improvement of 5% points from 2015. This was followed by a 26% pay gap in the IT sector, nearly 22% in the BFSI sector and 15% in education and research.

Sanjay Modi, managing director (APAC & Middle East), Monster.com, said, “In India, the gender pay gap story holds true and the overall gap across India Inc is at 25%. This primarily is a manifestation of the underlying diversity challenges that organisations currently face. There is a dire need for tangible initiatives to bridge this pay gap with removing structural impediments to women's growth, providing ac cess to skills training, jobs, and decision-making.“

According to a `Women of India Inc' survey , which aimed at understanding women's workplace concerns, nearly 44% women feel that gender parity need not be a top priority. On the other hand, almost 69% expressed that even if gender parity is a priority , the management “does not walk the talk“. Over 13% feel absence of proper child care is one of the biggest challenges for women.

“Unexamined conventions of women's commitment to work, distractions of family commitments, societal perception of women who work for long hours, etc, are the challenges that constrain women's progress. Sensitisation towards gender diversity and a step towards examining our socialised preconceptions would help break barriers to a more fair and inclusive work environment,“ said Modi on the separate survey , `Women of India Inc', which was conducted on Monster India's database capturing responses from over 2000 working women.

See also

Migration Abroad For Employment Women

Women In Armed Forces: Delhi HC Ruling