Tibet: A brief history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

From ancient times to 2014: a timeline

The authors of this section are

and

Ancient History

Tibet is an ancient country located between India and China in the Great Himalayan mountains. Known as the “Roof of the world” or the “Land of Snows”, During Tibet’s ancient history it existed as a single independent country of Tibet. Tibet was unified as a single country under King Songtsan Gampo in the 7th century. The Tibetan empire extended into large parts of China and Central Asia. Buddhism was established as the religion in Tibet assimilating the local Bon traditions. Tibetan language is spoken in Tibet. The lineage of the Dalai Lamas became the spiritual and political leaders in Tibet. They are believed to the recognised reincarnations of the Buddha of Compassion. (Bath Tibet Support)

7th-9th century - Namri Songzen and descendants begin to unify Tibetan-inhabited areas and conquer neighbouring territories, in competition with China. (BBC)

In 821 / 822 CE, Tibet and China signed a peace treaty that delineates borders. A bilingual account of the treaty including the details of the borders between the two countries are inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa. (Bath Tibet Support)

1244 - Mongols conquer Tibet. Tibet enjoys considerable autonomy under Yuan Dynasty. (BBC)

1598 - Mongol Altan Khan makes high lama Sonam Gyatso first Dalai Lama. (BBC)

1630s-1717 - Tibet involved in power struggles between Manchu and Mongol factions in China. (BBC)

1624 - First European contact as Tibetans allow Portuguese missionaries to open church. Expelled at lama's insistence in 1745. (BBC)

1717 - Dzungar (Oirot) Mongols conquer Tibet and sack Lhasa. Chinese Emperor Kangxi eventually ousts them in 1720, and re-establishes rule of Dalai Lama. (BBC)

1724 - Chinese Manchu (Qing) dynasty appoints resident commissioner to run Tibet, annexes parts of historic Kham and Amdo provinces. (BBC)

1750 - Rebellion against Chinese commissioners quelled by Chinese army, which keeps 2,000-strong garrison in Lhasa. Dalai Lama government appointed to run daily administration under supervision of commissioner. (BBC)

1774 - British East India Company agent George Bogle visits to assess trade possibilities. (BBC)

1788 and 1791 - China sends troops to expel Nepalese invaders. (BBC)

1793 - China decrees its commissioners in Lhasa to supervise selection of Dalai and other senior lamas. (BBC)

Foreigners banned (BBC)

1850s - Russian and British rivalry for control of Central Asia prompts Tibetan government to ban all foreigners and shut borders. (BBC)

1865 - Britain starts discreetly mapping Tibet. (BBC)

1904 - Dalai Lama flees British military expedition under Colonel Francis Younghusband. Britain forces Tibet to sign trading agreement in order to forestall any Russian overtures. (BBC)

1904 – British military expedition led by Colonel Francis Younghusband enters Lhasa and UK trade mission established under the Lhasa treaty agreed with the Tibetan government. (Bath Tibet Support)

1906 - British-Chinese Convention of 1906 confirms 1904 agreement, pledges Britain not to annex or interfere in Tibet in return for indemnity from Chinese government. (BBC)

1907 - Britain and Russia acknowledge Chinese suzerainty over Tibet. (BBC)

1908-09 - China restores Dalai Lama, who flees to India as China sends in army to control his government. (BBC)

1911 – the UK government recognises Tibet as de facto independent and official communications are conducted directly with the Tibetan government. (Bath Tibet Support)

1912 April - Chinese garrison surrenders to Tibetan authorities after Chinese Republic declared. (BBC)

Independence declared (BBC)

1912 - 13th Dalai Lama returns from India, Chinese troops leave. (BBC)

1913 - Tibet reasserts independence after decades of rebuffing attempts by Britain and China to establish control. (BBC)

1935 - The man who will later become the 14th Dalai Lama is born to a peasant family in a small village in north-eastern Tibet. Two years later, Buddhist officials declare him to be the reincarnation of the 13 previous Dalai Lamas. (BBC)

1937 – Two year old Lhamo Thondup is recognised as the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama and is named Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Tenzin Gyatso – the current 14th Dalai Lama who now lives in exile in India. He begins his education as a Buddhist monk. (Bath Tibet Support)

1948 – The United Nations Universal Declaration for Human Rights was set out and proclaims “Recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”. (Bath Tibet Support)

1949 - Mao Zedong proclaims the founding of the People's Republic of China and threatens Tibet with "liberation". (BBC)

1949 – The People’s Liberation Army of the People’s Republic of China cross the Tibetan border and begin the process of the ‘liberation’ of Tibet. (Bath Tibet Support)

1950 - China enforces a long-held claim to Tibet. The Dalai Lama, now aged 15, officially becomes head of state. (BBC)

1950 – In October, over 40,000 Chinese troops attack the capital of the Tibetan region of Chamdo. The 8,000 strong Tibetan army are quickly crushed with over 4000 Tibetans killed. On 17th November an emergency session of the Tibetan National Assembly is convened. The Dalai Lama only at 15 assumes full authority as Head of State. (Bath Tibet Support)

1951 – Under extreme pressure, a Tibetan delegation in Beijing sign the 17 point agreement. In return for pledging to guarantee Tibet’s autonomy and respect the Buddhist religion and culture of Tibet, this gives China control over Tibet’s external affairs and allows Chinese military occupation. The agreement is NOT recognised by the Tibetan government. Over 20,000 troops enter Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. (Bath Tibet Support) 1951 - The "Seventeen Point Agreement", professes to guarantee Tibetan autonomy and to respect the Buddhist religion, but also allows the establishment of Chinese civil and military headquarters at Lhasa. (BBC)

Mid-1950s - Mounting resentment against Chinese rule leads to outbreaks of armed resistance. (BBC)

1954 - The Dalai Lama visits Beijing for talks with Mao, but China still fails to honour the Seventeen Point Agreement. (BBC)

1954 – The young Dalai Lama travels to Beijing to engage in peace talks with Mao Tse-tung and other Chinese leaders. His efforts are thwarted by Beijing’s unflinching and ruthless stance. (Bath Tibet Support)

Revolt (BBC)

10th March 1959 – With fears for the Dalai Lama’s life, Lhasa erupts into protest calling on China to leave Tibet. The uprising is brutally crushed by the occupying Chinese army and over the next six months around 87,000 Tibetans are killed as a result of the unrest. (Bath Tibet Support) 1959 March - Full-scale uprising breaks out in Lhasa. Thousands are said to have died during the suppression of the revolt. The Dalai Lama and most of his ministers flee to northern India, to be followed by some 80,000 other Tibetans. (BBC)

12th March 1959 – Tibetan Women’s Association formed in Lhasa to challenge the Chinese occupation of Tibet. Over 15,000 women demonstrate against Chinese occupation. Protesting peacefully outside the Potala Palace many of these women suffered brutally at the hands of the Chinese troops. They were arrested, imprisoned and tortured without trial. Most of those imprisoned did not survive. (Bath Tibet Support)

17th March 1959 – The Dalai Lama disguised as a soldier leaves Lhasa to escape to India over the Himalayan mountains. En-route to India, he declared the new administration installed in Lhasa was totally controlled by the Chinese and not recognised by the people of Tibet. Upon arrival in India, the Dalai Lama re-established the Tibetan government in exile. In the ensuing months over 80,000 Tibetans cross the Himalayas to India. (Bath Tibet Support)

1959 – The Tibet Society, the worlds first Tibet support group was formed by Hugh Richardson who was the British representative in Lhasa in the 30’s and 40’s along with other ex-diplomats and foreign office officials. (Bath Tibet Support)

1959, 1961, 1965 – Resolutions in support of Tibet are passed at the United Nations calling for respect of the fundamental rights of the Tibetan people and their distinctive cultural and religious life. (Bath Tibet Support)

Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1959 – 1962) led to great famine in Tibet. Approximately 1.2 million Tibetans are estimated to have died since 1950 due to violence, torture, starvation and other causes under the Chinese Rule. (Bath Tibet Support)

1963 – Tibet is sealed off and foreign visitors are banned. The shut down lasts eight years until 1971. The Dalai Lama approved a democratic constitution for the Tibetan people and began the development of the world’s newest democracies. (Bath Tibet Support)

1965 – Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) is established by the Chinese government. (Bath Tibet Support)

1966 – The Cultural Revolution reaches Tibet resulting in widespread destruction of thousands of monasteries, with monks and nuns cast out into the land. Many ancient and valuable religious and cultural artefacts were destroyed. (Bath Tibet Support)

1970’s – Ongoing program of large scale relocation of Han Chinese into Tibet. (Bath Tibet Support)

1971 - Foreign visitors are again allowed to enter the country. (BBC)

Late 1970s - End of Cultural Revolution leads to some easing of repression, though large-scale relocation of Han Chinese into Tibet continues. (BBC)

1980s - China introduces "Open Door" reforms and boosts investment while resisting any move towards greater autonomy for Tibet. (BBC)

1987 – At the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in Washington, the Dalai Lama proposes a Five-Point Peace Plan as a first stage towards resolving the conflict in Tibet. (Bath Tibet Support)

1987 - The Dalai Lama calls for the establishment of Tibet as a zone of peace and continues to seek dialogue with China, with the aim of achieving genuine self-rule for Tibet within China. (BBC)

1988 – In an address to the European Parliament in Starsbourg, the Dalai Lama elaborates on the Five Point Peace Plan and puts forward his “Middle Way” approach. This suggests a meaningful autonomy within the People’s Republic of China, whereby Tibet would be a self governing democratic political entity founded on the agreement of the people for common good. Protests occur in Tibet which are crushed. (Bath Tibet Support)

1988 - China imposes martial law after riots break out. (BBC)

1989 – The Dalai Lama is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. (Bath Tibet Support)

1993 – Behind the scenes the contact between the Dalai Lama and the Chinese government are broken off. (Bath Tibet Support)

1995 – Six year old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima is recognised by the Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second most important figure in Tibetan Buddhism. Chinese authorities place the boy under arrest and another six year old boy Gyancain Norbu is nominated as their official Panchen Lama. The recognised Panchen Lama and his family are missing till today and their whereabouts are unknown. (Bath Tibet Support)

2002 – Communication between the Dalai Lama and the Chinese government resumes after a break of nine years with a round of informal discussions in Beijing. Since then there have been five further rounds of talks with no tangible results. (Bath Tibet Support)

Rail link (BBC)

2006 July – The Golmud-Lhasa railway link opens bringing mass tourism from mainland China and an added huge influx of Han Chinese migrants further marginalising Tibetans inside Tibet. Mandarin is now the commonly used language in Lhasa. (Bath Tibet Support)

October 2007 – President George Bush presents the Dalai Lama with top civilian medal in the US, the Congressional Gold Medal. (Bath Tibet Support)

The Chinese regime steps up its re-education policy where Tibetan monks and nuns are forced to denounce their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. Refusal results in years of imprisonment, torture and death in the infamous prisons such as the Drapchi prison. (Bath Tibet Support)

For example Tibetan woman Ngawang Sangdrol who spent several years being held and tortured at Drapchi prison. After lobbying by individuals, organisations, French, Swiss and American governments, she was released on medical parole from Drapchi prison in October 2002. She has quoted that all political prisoners are tortured and the Chinese authorities adopt a lenient position in terms of the torture towards a prisoner if international attention is mobilised. (Bath Tibet Support)

The human rights casualties are not possible and very painful to include in a leaflet. Please refer to the Tibet Society or Amnesty website www.tibetsociety.com or www.amnesty.org.uk. (Bath Tibet Support)

2007 November - The Dalai Lama hints at a break with the centuries-old tradition of selecting his successor, saying the Tibetan people should have a role. (BBC)

2007 December - The number of tourists travelling to Tibet hits a record high, up 64% year on year at just over four million, Chinese state media say. (BBC)

2008 March - Anti-China protests escalate into the worst violence Tibet has seen in 20 years, five months before Beijing hosts the Olympic Games. (BBC)

March 2008 – In desperation of the increasingly hard line policies of the Chinese authorities, monks demonstrate in Lhasa on the 10th March. Following a severe crackdown by the local Chinese regime, protests and demonstrations by Tibetan people spread throughout the Tibetan Autonomous Region and other traditionally Tibetan areas. Hundreds of Tibetans are killed or injured by the Chinese Government’s Police and troops. Thousands more are detained. (Bath Tibet Support)

Pro-Tibet activists in several countries focus world attention on the region by disrupting progress of the Olympic torch relay. (BBC)

2008 October - The Dalai Lama says he has lost hope of reaching agreement with China about the future of Tibet. He suggests that his government-in-exile could now harden its position towards Beijing. (BBC)

2008 November - The British government recognises China's direct rule over Tibet for the first time. Critics say the move undermines the Dalai Lama in his talks with China. (BBC)

China says there has been no progress in the latest round of talks with aides of the Dalai Lama, and blames the Tibetan exiles for the failure of the discussions. (BBC)

A meeting of Tibetan exiles in northern India reaffirms support for the Dalai Lama's long-standing policy of seeking autonomy, rather than independence, from China. (BBC)

2008 December - Row breaks out between European Union and China after Dalai Lama addresses European MPs. China suspends high-level ties with France after President Nicolas Sarkozy meets the Dalai Lama. (BBC)

Anniversary (BBC)

2009 January - Chinese authorities detain 81 people and question nearly 6,000 alleged criminals in what the Tibetan government-in-exile called a security crackdown ahead of the March anniversary of the 1959 flight of the Dalai Lama. (BBC)

2009 March - China marks flight of Dalai Lama with new "Serfs' Liberation Day" public holiday. China promotes its appointee as Panchen Lama, the second-highest-ranking Lama, as spokesman for Chinese rule in Tibet. Government reopens Tibet to tourists after a two-month closure ahead of the anniversary. (BBC)

2009 April - China and France restore high-level contacts after December rift over President Sarkozy's meeting with the Dalai Lama, and ahead of a meeting between President Sarkozy and China's President Hu Jintao at the London G20 summit. (BBC)

2009 August - Following serious ethnic unrest in China's Xinjiang region, the Dalai Lama describes Beijing's policy on ethnic minorities as "a failure". But he also says that the Tibetan issue is a Chinese domestic problem. (BBC)

2009 October - China confirms that at least two Tibetans have been executed for their involvement in anti-China riots in Lhasa in March 2008. (BBC)

2009 January - Head of pro-Beijing Tibet government, Qiangba Puncog, resigns. A former army soldier and, like Puncog, ethnic Tibetan, Padma Choling, is chosen to succeed him. (BBC)

2010 April - Envoys of Dalai Lama visit Beijing to resume talks with Chinese officials after a break of more than one year. (BBC)

Self-immolations (BBC)

2011 March - A Tibetan Buddhist monk burns himself to death in a Tibetan-populated part of Sichuan Province in China, becoming the first of 12 monks and nuns in 2011 to make this protest against Chinese rule over Tibet. (BBC)

2011 April - Dalai Lama announces his retirement from politics. Exiled Tibetans elect Lobsang Sangay to lead the government-in-exile. (BBC)

2011 July - The man expected to be China's next president, Xi Jinping, promises to "smash" Tibetan separatism in a speech to mark the 60th anniversary of the Chinese Communist takeover of Tibet. This comes shortly after US President Barack Obama receives the Dalai Lama in Washington and expresses "strong support" for human rights in Tibet. (BBC)

2011 November - The Dalai Lama formally hands over his political responsibilities to Lobsang Sangay, a former Harvard academic. Before stepping down, the Dalai Lama questions the wisdom and effectiveness of self-immolation as a means of protesting against Chinese rule in Tibet. (BBC)

2011 December - An exiled Tibetan rights group says a former monk died several days after setting himself on fire. Tenzin Phuntsog is the first monk to die thus in Tibet proper. (BBC)

2012 May - Two men set themselves on fire in Lhasa, one of whom died, the official Chinese media said. They are the first self-immolations reported in the Tibetan capital. (BBC)

2012 August - Two Tibetan teenagers are reported to have burned themselves to death in Sichuan province. (BBC)

2012 October - Several Tibetan men burn themselves to death in north-western Chinese province of Gansu, Tibetan rights campaigners say. (BBC)

2012 November - UN human rights chief Navi Pillay calls on China to address abuses that have prompted the rise in self-immolations. (BBC)

On the eve of the 18th Communist Party of China National Congress, three teenage Tibetan monks set themselves on fire. (BBC)

2013 February - The London-based Free Tibet group says further self-immolations bring to over 100 the number of those who have resorted to this method of protest since March 2011. (BBC)

2013 June - China denies allegations by rights activists that it has resettled two million Tibetans in "socialist villages". (BBC)

2014 February - US President Obama holds talks with the Dalai Lama in Washington. China summons a US embassy official in Beijing to protest. (BBC)

2014 April - Human Rights Watch says Nepal has imposed increasing restrictions on Tibetans living in the country following pressure from China. (BBC)

2014 June - The Tibetan government-in-exile launches a fresh drive to persuade people across the world to support its campaign for more autonomy for people living inside the region. (BBC)

1720- 1950: Chinese and British Interventions

CHINESE AND BRITISH INTERVENTIONS IN TIBET | Lhassa.org

CHINESE AND BRITISH INTERVENTIONS

Following interior quarrels, the Chinese intervene in Tibet in 1720 and establish their domination.

The interest which carries the Chinese emperor in Tibet is initially of a strategic nature because this one is located in full heart of the Asian continent. This is why, on the order of Beijing, the country is closed to foreign visitors and will remain insulated until 1904.

In 1904, Great Britain imposes its protectorate on the Transhimalayan dependences of Tibet (Nepal, Burma, Sikkim) and sends an armed detachment in Lhassa.

After the withdrawal of the British (1908), the Chinese occupy Tibet until 1911, date of the Chinese revolution which marks the collapse of the dynasty of Qing.

In 1913, the 13th Dalaï Lama, Thubten Gyatso, proclaim the independence of Tibet and expel the Chinese out of the borders of Tibet. It creates the monetary unit: the sang.

Mongolia, which proclaimed its independence since 1911, and Tibet recognize each other.

On October 1, 1949, the Peoples’ Republic of China is proclaimed, with Mao Zedong as leader.

In September 1950,80 000 soldiers of president Mao invade Tibet, in spite of a resistance of 8500 Tibetan combatants, country is completely invaded in only a few days.

Whereas the Chinese soldiers continue their progression, the Dalaï Lama, who is then 17 years old, on November 17, 1950 is emancipated. He can then control its state.

In April 1951, Tibetan delegates arrived at Beijing provided with full powers of the local government of Tibet. Negotiations are carried out.

Following these discussions, the two parts are agreed to conclude a 17 points agreement.

The United States advises the Dalaï Lama to be unaware of this agreement, but this one had, under the constraint, to resign itself to sign it.

The late 1850s (From The Wise Collection)

Posted by Ursula Sims-Williams

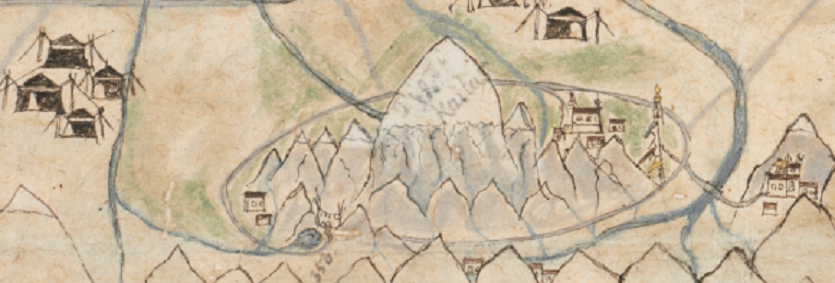

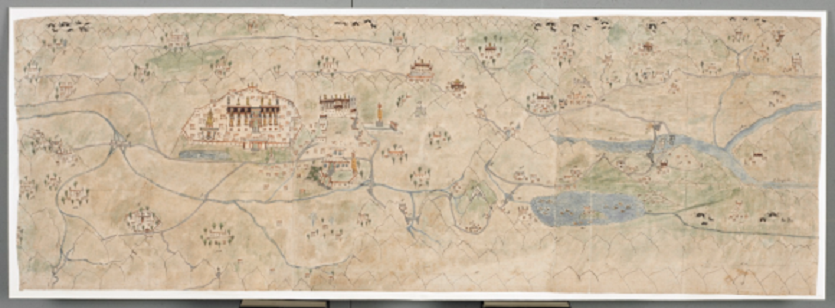

The drawings in the British Library’s Wise Collection probably form the most comprehensive set of large-scale visual representations of mid-nineteenth century Tibet and the Western Himalayan kingdoms of Ladakh and Zangskar. These drawings were made in the late 1850s – at a time when the mapping of British India was largely complete, but before or around the time when Tibet began to be mapped for the first time by Indian Pundits.

The acquisition of systematic knowledge of Tibetan landscapes and societies became an ambitious goal for the British Empire in the 19th century. Such knowledge was often dependent on the aid of local informants. As a result the region was occasionally culturally represented and visualized by local people – such as in case of the Wise Collection.

The story of the collection’s origin is a puzzle that has only become accessible piece by piece. The collection was named after Thomas Alexander Wise (1802-1889), a Scottish polymath and collector who served in the Indian Medical Service in Bengal in the first half of the 19th century.

According to a typewritten note dating from the 1960s, the ‘drawings appear to be by a Tibetan artist, probably a lama, who had contact with Europeans and had developed a semi-European style of drawing.’I have recently uncovered one of the most important parts of the whole ‘Wise puzzle’ – the name of the Scotsman who commissioned the drawings. It was William Edmund Hay (1805-1879), former assistant commissioner of Kulu in today’s Northwest India. Charles Horne writes (Horne 1873: 28)

In the year 1857 one of the travelling Llamas [lamas] from Llassa [Lhasa] came to Lahoul, in the Kûlû country on the Himalêh [Himalaya], and hearing of the mutiny [this refers to the Indian rebellion in 1857] was afraid to proceed. Major Hay, who was at that place in political employ, engaged this man to draw and describe for him many very interesting ceremonies in use in Llassa, […].

William Howard Russell – former special correspondent of The Times – visited Simla in July 1858 and mentions in his diary that ‘Major Hay, formerly resident at Kulu, is here on his way home, with a very curious and valuable collection of Thibetan drawings’ (Russell 1860: 136). These statements most probably refer to the drawings that now form the British Library’s Wise Collection. At the current state of research no definitive statement can be made about the circumstances in which Wise acquired the drawings; most probably Hay sold them to him.

The name of the lama who made the drawings also remains unknown, but I have started following the traces he left and hope to identify him one day.

The explanatory notes: 36: Remains of a very old fort. There were said to have been 3 sisters; one built a fort, a second erected 108 chortens [stupas], and the third planted the place with trees: there is this place. 37: A hot spring only visible in winter, as in summer when the river has swollen it over flows it.

The collection comprises six large picture maps – drawn on 27 sheets in total – which add up to a panorama of the 1,800 km between Ladakh and Central Tibet. They are accompanied by 28 related drawings illustrating monastic rituals, ceremonies, etc. referring to places shown on the maps. Placed side by side, the maps present a continuous panorama measuring more than fifteen metres long. Places on the maps are consecutively numbered from Lhasa westwards. Taken together there are more than 900 numbered annotations on the drawings. Explanatory notes referring to the numbers on the drawings were written on separate sheets of paper. Full keys exist only for some maps and for most of the accompanying drawings; other drawings are mainly labelled by captions in Tibetan, while on others English captions dominate.

Some drawings lack both captions and explanatory texts. Watermarks on the paper together with internal evidence from the explanatory notes and from the drawings themselves support the fact that the drawings were created in the late 1850s.

Bridge

Compared to maps created by Westerners the picture maps in the Wise Collection are not primarily concerned with topographical accuracy, but provide a much wider range of visual information. They transmit valuable ideas about the artist’s perception and representation of the territory they illustrate. The panorama shown on the maps represents the area along the travel routes that were used by several groups of people in mid-19th century Tibet – such as traders, pilgrims and officials. The maps present information about topographical characteristics such as mountains, rivers, lakes, flora, fauna and settlements. Furthermore a large amount of detailed information on infrastructure such as bridges, ferries, travel routes, roads and mountain passes is depicted. Illustrations of monasteries, forts and military garrisons – the three main seats of power in mid-19th century Tibet – are highlighted. Thus the drawings supply information not only about strategic details but also about spheres of influence. The question of what purpose the maps served remains a matter for speculation at present. William Edmund Hay was experienced in surveying and mapmaking – he travelled not only in the areas around Kulu, but also in Ladakh and in the Tibetan borderlands. He was also a collector with varied cultural interests.

He never had the chance to travel to Central Tibet himself, but his interest in acquiring knowledge about Tibet were characterised by an encyclopaedic approach: he wanted to gather as wide a range of information on the area as possible.

What makes the Wise Collection so fascinating is the fact that it can be studied from different disciplines. On the one hand the picture maps can be assigned to Tibetan cartography and topography; on the other they represent an illustrated ‘ethnographic atlas’. Supplemented by the accompanying drawings and explanatory notes, the Wise Collection represents a ‘compendium of knowledge’ on Tibet.

When I started doing research on the Wise Collection I thought I knew where I was going. But the longer I studied the material and the deeper understanding I gained of the collection as a whole, the more new questions emerged. I realized that the drawings require a wider frame of analysis in their understanding. Thus I focused not just on the stories in the drawings but also on the story of the drawings. The expected results of my research will expand our knowledge about the connection between the production of knowledge and cultural interactions. As the result of a collaborative project of at least two people with different cultural backgrounds, the Wise Collection reflects a complex interpretation of Tibet commissioned by a Scotsman and created by a Buddhist monk. The result of their collaboration represents a ‘visible history’ of the exploration of Tibet. The entire Wise Collection and my research results will be published in my forthcoming large-format monograph.

The whole collection was restored and digitised in 2009 and is available on British Library Images Online (search by shelfmark). The drawings are catalogued as the ‘Wise Albums’ under the shelfmark Add.Or.3013-43.

Originally all the drawings were bound in three large red half-leather albums. The related drawings and the relevant explanatory notes are still bound in these albums. The large picture maps have been removed and window-mounted for conservation reasons.

The Lhasa map was on display in the exhibition Tibet's Secret Temple held at the Wellcome earlier this year and several of the drawings will also be exhibited in Monumental Lhasa: Fortress, Palace, Temple, opening in September 2016 at the Rubin Museum of Art, New York.

1904-51

A very brief history

The Chinese occupation of Tibet gives Beijing great strategic depth and control over river waters in Asia.

The stand-off between India and Bhutan on one side and China on the other at Doklam, a tri-junction once between India, Tibet and Bhutan, and the larger border dispute between the two Asian giants, have their origins in the British invasion of Tibet in 1904.

At the turn of the 20th century, the geopolitical balance between a crumbling Manchu empire and India was massively in favour of British India. Those were the days of the Great Game, a contest to gain influence from Iran to Tibet, played out between British India and an expanding Tsarist Russia. It was to ward off any perceived Russian influence in Tibet that Lord Curzon dispatched Colonel Younghusband on what the British called their Tibet 'expedition'.

However, the greatest impact of the British invasion of Tibet was on Manchu China. The Qing dynasty and all previous successive dynasties saw the marauding Mongol nomads as the enduring threat to the security of the empire. In the 19th century, a new threat for the empire sailed from across the seas. Western powers subjected China to what the Chinese call 'a century of humiliation'.

While grappling with this new danger posed by the western powers, Manchu China considered Tibet its secure backyard, or as one Manchu official put it, "the hand that protects the face". The Tibetan plateau, shooting up almost three miles in the air, covering a total landmass of 2.5 million square kilometres and ringed by the mightiest mountain range in the world, was considered impregnable. However, the British breach of this buffer in 1904, which had kept the peace between India and China for centuries, alerted a dying Manchu China to the absolute necessity of securing Tibet. Manchu general Zhou Erfeng invaded Tibet in 1908. The 13th Dalai Lama fled Tibet and sought refuge in India.

The People's Republic of China's invasion of Tibet in 1949-1950 was a continuation of the strategy to fend off hostile powers from the fringes of the empire. China's occupation of Tibet gives Beijing immense strategic depth and control over most of the river waters of Asia.

The 2017 stand-off at Doklam, or as the Tibetan historian Tsering Shakya puts it, Droglam (the nomads' path), China's One Belt One Road project, the militarisation of the plateau and its massive infrastructure building in Tibet are all part of China re-starting the Great Game: expanding Chinese influence across the Himalayas and Central Asia, all the way to Europe.

Mao Zedong, a keener student of The Art of War than of Das Kapital, saw Tibet in strategic terms. He said the Tibetan plateau, which the celebrated Swedish explorer Sven Hedin described as the 'most stupendous upheaval on the face of the earth', was the palm, with Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh as the 'five fingers'. With China gaining influence in Nepal, now threatening to recognise Sikkim as independent and obliquely hinting at stoking a democratic revolution in the kingdom of Bhutan when it says the "Bhutanese are not a happy lot", Beijing may have plans to join the 'fingers' to the 'palm'.

In the 17-Point agreement signed between Lhasa and Beijing in 1951, China promised to respect the autonomy of Tibet..

Thubten Samphel is the director of the Tibet Policy Institute and the author of Falling through the Roof

The 1904 battle at Gyantse, and after

EDWARD WONG| China Seizes on a Dark Chapter for Tibet| AUG. 9, 2010 | The New York Times

GYANTSE, Tibet — The white fortress loomed above the fields, a crumbling but still imposing redoubt perched on a rock mound above a plain of golden rapeseed shimmering in the morning light.

A battle here in 1904 changed the course of Tibetan history. A British expedition led by Sir Francis E. Younghusband, the imperial adventurer, seized the fort and marched to Lhasa, the capital, becoming the first Western force to pry open Tibet and wrest commercial concessions from its senior lamas.

The bloody invasion made the Manchu rulers of the Qing court in Beijing realize that they had to bring Tibet under their control rather than continue to treat it as a vassal state.

So, in 1910, well after the British had departed, 2,000 Chinese soldiers occupied Lhasa. That ended in 1913, after the disintegration of the Qing dynasty, ushering in a period of de facto independence that many Tibetans cite as the modern basis for a sovereign Tibet.

The Chinese Communists seized Tibet again in 1951, perhaps influenced by the Qing emperor’s earlier decision to invade the mountain kingdom.

These days, Gyantse resembles other towns in central Tibet. Its dusty roads are lined with shops and restaurants run by ethnic Han migrants, whom many Tibetans see as the most recent wave of invaders.

But Chinese officials prefer to direct the world’s attention away from that and to the brutal events at Gyantse in 1904, which conveniently fit into their master narrative for Tibetan and Chinese history.

The Chinese government insists Tibet is an “inalienable” part of China, and it has appropriated the 1904 invasion as another chapter in the long history of imperialist efforts to dismantle China — what the Communist education system calls the “100 years of humiliation.”

In that Communist narrative of Gyantse, the Tibetans are a stand-in for the Chinese who were victimized by foreign powers during the Qing dynasty.

“The local people resisted the British there,” said Dechu, a Tibetan woman from the foreign affairs office in Lhasa who accompanied foreign journalists on a recent official tour of Tibet. “They put up a great resistance, so it’s called the City of Heroes.”

In the late 1990s, when Britain was handing Hong Kong back to China, the Chinese government started a propaganda campaign to highlight that theme.

A melodramatic movie about the 1904 British invasion, “Red River Valley,” was released in 1997. It was a hit, and Chinese still rave about it. It was also required viewing for officials in Tibet and for many schoolchildren.

“I’ve also seen a musical, two plays, another feature film and a novella on the same topic, all from that time,” Robert Barnett, a Tibet scholar at Columbia University, said of the late 1990s. He said that he had not seen any reference in Tibetan literature to Gyantse as the City of Heroes before then.

In 2004, the centenary of the British invasion, officials staged activities to commemorate it, including a musical, “The Bloodbath in the Red River Valley.” Then there is the museum in the fort. A sign in English once identified it as “the Memorial Hall of Anti-British.” In 1999, it displayed “shoddy relief sculptures of battle scenes, with unintelligible captions,” according to Patrick French, a historian who described his visit there in his book “Tibet, Tibet.”

So what did happen in Gyantse in 1904?

The Younghusband expedition was sent by Lord Curzon, the viceroy of India, to force the 13th Dalai Lama to agree to commercial concessions. Tibet had also begun to figure prominently in what was known as the Great Game, where the British and Russian empires vied for influence in Central Asia.

British officials had heard of a Russian presence in the court of the Dalai Lama and wanted to learn the truth. That meant getting officers to Lhasa, which had never been done before.

Colonel Younghusband was teamed with Brig. Gen. J. R. L. Macdonald to lead a force from Sikkim, in British India, across the Jelap Pass into Tibet. They crossed the border on Dec. 12, 1903, with more than 1,000 soldiers, 2 Maxim guns and 4 artillery pieces, according to “Trespassers on the Roof of the World,” a history of Western efforts to open Tibet, by Peter Hopkirk. Behind them, in the snow, trailed 10,000 laborers, 7,000 mules, 4,000 yaks and 6 camels.

Outside the village of Guru, they encountered an encampment of 1,500 Tibetan troops. Hostilities broke out. The British troops, which included Sikhs and Gurkhas, opened fire. In four minutes, 700 poorly armed Tibetans lay dead or dying.

Later, at Red Idol Gorge, a narrow defile just 20 miles from Gyantse, the British slaughtered another 200 Tibetans.

The Tibetans made their final stand at the fort at Gyantse, called a dzong, or jong, in Tibetan. After they missed a deadline to surrender on July 5, the British attacked from the southeast corner of the fort.

A thin line of officers and soldiers clambered up the sheer rock face. “The steepness was so great that a man who slipped almost necessarily carried away the man below him also,” wrote Perceval Landon of The Times of London.

The Tibetans rained down ammunition and stones. But one lieutenant and an Indian soldier made it through the breach, followed by others. The Tibetans fled, shimmying down two ropes.

“The surrender of the jong was to have a crushing effect on Tibetan morale,” Mr. Hopkirk wrote. “There was an ancient superstition that if ever the great fortress were to fall into the hands of an invader, then further resistance would be pointless.”

The British reached Lhasa soon afterward. Two months later, the evening before leaving Lhasa for good, Colonel Younghusband rode out to a mountain and gazed down at the ancient city, where he experienced a curious epiphany that inspired him to end all acts of bloodshed and found a religious movement, the World Congress of Faiths.

“This exhilaration of the moment grew and grew till it thrilled through me with overpowering intensity,” he wrote in a memoir, “India and Tibet.” “Never again could I think evil, or ever again be at enmity with any man. All nature and all humanity were bathed in a rosy glowing radiancy; and life for the future seemed naught but buoyancy and light.”

Helen Gao contributed research from Beijing.

1912-1933: British policy and the 'development' of Tibet

UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG THESIS COLLECTION 1954-2016

British policy and the 'development' of Tibet 1912-1933

[By] Heather Spence, University of Wollongong, 1993

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts

Spence, Heather, British policy and the 'development' of Tibet 1912-1933, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 1993. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1433

Abstract

Two conflicting views of Tibet's political status in relation to China have dominated both popular and scholarly literature. The 'pro-Chinese' school views Tibet as a traditional, integral part of China. Tibet, they maintain, was separated from China after the fall of the Manchu dynasty as a consequence of British machinations. Tibet was justifiably reunited with China, the 'motherland', in 1951. The 'pro-Tibetan' school argues that the partnership was between the Dalai Lama and the Manchus: that relationship ended with the collapse of the Manchu dynasty. Accordingly, Tibet is seen as an independent state conquered by the Chinese Communists and illegally incorporated into the Chinese state.

This study is not an attempt to enter that debate, but rather to fill a gap in a neglected aspect of Tibetan studies. Nonetheless, the results of this study will, no doubt, become a component in the highly politicized nature of Tibetan history. Sir Charles Bell's authoritative Tibet. Past and Present (1924) and Portrait of a Dalai Lama (1946) both stand as important primary sources for this study. As secondary sources dealing with British policy, W. D. Shakabpa's pioneering study Tibet: A Political History (1967), P. Mehra's The McMahon Line and After (1974) and A.K.J. Singh's Himalayan Triangle (1988) are indispensable. Alastair Lamb's most recent study, Tibet. China and India 1914-1950 (1989), is the first publication to deal with this period in detail. Lamb expertly evaluates Anglo-Tibetan relations and narrows the gap which this thesis study is also designed to close.

However, by locating Anglo- Tibetan relations in the wider context of international politics, this dissertation will augment Lamb's study and contribute to the continuing intellectual debate in the field of Tibetan studies. Tibet has been significant in the political development of British India, for it was believed to be a key to the safety and security of India's north-eastern frontier. When the British consolidated their power in the sub-continent of India, they were also faced with the problem of securing a stable frontier on India's Himalayan borders. The British government, therefore, had to evolve a definite policy towards the Himalyan kingdoms, especially Tibet. British India's policy during the 19th century was to treat Tibet as a buffer state.

There can be no doubt that the loss of Tibet's independence stems directly from the failure of the British Govemment's Younghusband Mission of 1904 to achieve what the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, hoped would result from it. Curzon believed that the M. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (Berkely, 1989), p. xv. 11 only way to guarantee the continuance of Tibet as a buffer was to ensure the predominance of British influence at Lhasa. This was to be achieved by bringing Tibet under some measure of British protection or influence. Curzon believed that British influence was essential because unless Britain laid claim to Tibet, Russia would draw Tibet into its sphere of influence. After the First World War Britain again had an opportunity to become Tibet's 'protector' but as was the case after 1904, chose to abandon Tibet to Chinese expansionism. Tibet, even today, conjures up images of 'Shangri-la', 'the savage and the sublime' and, perhaps, 'paradise lost'. It is, however, far from remote or picayune to world history. Tibet represents the interface between the two most populous nations on earth and marks the site of one of the most complex boundary disputes ever to disturb the peace of nations. The problems on India's northern frontiers have become a tangled mass of diplomatic perplexity to the governments and people of India and China. The loss of Tibet as a buffer zone between two major world powers has produced major long-term consequences.

The Chinese domination of Tibet has presented the current Indian Republic with just those dangers which Curzon feared would confront the British-Indian Empire from the extension into Tibet of the influence of Tsarist Russia. Tibet's role today as a garrison state of China goes far towards explaining its important place in current Westem geopolitical thought. Tibet has become a major handicap to China's political stability. The fate of modern Tibet, and the problems of India's northern frontiers, are subjects of recent political debate. Tibet's destiny in a broader sense and in these days of national self-determination is now a concern of world conscience. It is difficult to comprehend the current situation in Tibet and its place in the policy of both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of India without an understanding of what happened during the period of British colonial domination in India.

The British carry some responsibility for the present state of affairs of Tibet. The question at issue is what responsibility should the British accept and what explanations are there for Britain's inability to prevent the loss of Tibetan independence? The answer to these questions lie in an analysis of the wider pattern of Anglo-Chinese political relations and of intemational relations after the First World War. Over the years scholars have trodden a well-wom path to the documents dealing with Anglo-Tibetan affairs held in the Public Record Office and the India Office Library. These documents have, more often than not, been used to compose historical surveys which examine chronological events and often result in Anglo-Tibetan relations being analysed in isolation from the broader intemational context.

The primary information on which this study is based provides a level of detail and understanding of the 1920s and I l l 1930s that has not previously been available. Many studies have been made of the 1904 Younghusband Mission, the 1913-14 Simla Conference and the later period of the 1940s and 1950s. The 1920s and 1930s have been overshadowed by the turbulent decades that preceded and succeeded them. These years have usually been given meaning only as a transition period and have assumed the character of a more or less featureless interval: a static period in Anglo-Tibetan relations. The relationship formed between British India and Tibet by the resolution of the 1914 Simla Conference appeared unaltered and fundamentally unquestioned until the transfer of power to an independent Indian government. This, however, was not the case. During this period two major policy shifts took place.

The apparent continuity conceals the intensity of debates over Tibetan policy in the British and Indian governments, especially during the years 1919-1921 and 1932-33, which disclosed Britain's apprehension about the volatile political situation in central and north Asia during and after the First World War. The destiny of Tibet has normally been treated as if it was almost exclusively determined by Anglo-Chinese relations. This approach ignores the fact that after the First World War the Tibetan question become an important component of a much broader controversy on the course of post-war British policy in Asia. The major reasons given for the Chinese incapacity to conclude a Tibetan agreement with Britain during the 1920s have been civil strife and popular opposition within China. The general consensus on the reason for Britain's inability to persuade the Chinese to resume negotiations is the aspiring mood of nationalism in China itself Indeed this is part of the answer, but the other part is that China was awakening to the fact that Britain's power and position in the Far East had been substanfially decreased because of the First World War.

Britain no longer had the diplomatic strength needed to bluff China into concluding a settlement of the Sino-Tibetan dispute. It is generally felt that China's intransigence and, at the same time, her weakness gave the Foreign Office no alternative but to sanction a policy of close Anglo-Tibetan relations without reference to China. On the surface this appears to be accurate but it overlooks the general context of Britain's economic situation in the Far East. This, in turn, reflected significant changes in the balance of power in Asia. Britain's position in the Far East had diminished and pressure from the British Legation in Peking, the Far Eastern Department of the Foreign Office and the British commercial community in China operated to shift the main emphasis of British policy in Asia from one of reliance on Japan to closer links with the United States and with a renascent China. With hindsight it can be seen that British policy decisions made during this period were crucial to Tibet's future. This study aims to place this period in the IV important position it should hold in any debate of Anglo-Tibetan relations. The 'forgotten years' deserve a more prominent place in Tibetan studies.

The beginning date of 1912, or in Tibetan, the year of Water-Mouse, was the year in which the 13th Dalai Lama returned from two years of exile in British India and declared independence for Tibet. 1933, the year of Water-Bird, was the year in which the 13th Dalai Lama died. The intervening years covered a period of Anglo-Tibetan relations which seem to indicate a movement towards the independence and development of Tibet under the umbrella of British influence. It can be seen in retrospect, however, that British influence in Tibet during the intervening years gradually declined. It was the realisation of this fact which prompted the major question: Why did Britain draw away from relations with Tibet? What were the socio-political and cultural issues that caused Britain to withdraw? The First World War did irreparable damage to the structure of imperialist diplomacy. This fact sets the stage for a discussion of Anglo-Tibetan relations during the 1920s and 1930s. The undermining of the old order came about in two ways.

On the one hand, Japanese expansion on the continent, coupled with the temporary distress of the European powers, destroyed the balance in the Far East which, though always precarious, the imperialists had managed to maintain. On the other hand, there were new forces undermining the very foundation of the old diplomacy - the 'new diplomacy' of the United States and the Soviet Union, and the self-conscious assertion of nationalism in China. It was Tibet's particular misfortune to be caught in the clutch of two powerful neighbours, Britain and China, who used her as a pawn in the compassionless game of political intrigue and diplomacy during the inter-war period. In attempting to answer the central question it is essential to connect the Anglo- Tibetan relationship to the intemational situation in which it operated. In tracing the British response to these intemational determinants, a chronological treatment is used. Each chapter therefore contains an evaluation which places Anglo-Tibetan relations in this wider context, identifying the economic, social and political ideas which set the historical boundaries within which British policy decisions operated.

The central problem of Britain's relations with Tibet has required research based on the archives of the British Foreign Office, housed in the Public Record Office in London, and supplemented by records in the India Office Library. These comprise a massive collection of letters, telegrams, notes, minutes, reports of the British and Indian governments, including many from the Tibetan and Chinese governments. The principal collection used are the Political and Secret Department Subject Files. The Australian National Library in Canberra has on microfilm the Foreign Office series relating to China which covers political correspondence from 1906 to 1922. In this series is a vast amount of information relating to Anglo-Tibetan relations. The Library also holds original copies of the Foreign Office Confidential prints (1840-), the only set outside Great Britain. Records and manuscripts held in the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, India, have also produced some information.

The private papers of Sir Charles Bell, Colonel Bailey, Colonel Weir, all of whom visited Lhasa during their time as British Political Officers, adds another dimension to the study. The diaries of Bell, Bailey, Frank Ludow, who set up the first British school in Tibet, and Captain R. S. Kennedy, who accompanied Bell to Lhasa as a medical officer, have also been consulted. These private papers are held at the India Office Library and the British Library. Books written by principal figures, such as Charles Bell, Eric Teichman, Henry Hayden, David Macdonald, WiUiam McGovem and Hugh Richardson, have also been studied as primary source material.

Publications by Tibetan authors, R. D. Taring, R. Lha-Mo, K. Dondup, D. N. Tsarong, D. Norbu and T. J. Norbu have contributed a valuable Tibetan perspective. Interviews with surviving participants and observers have been especially useful, particularly regarding personal character details. Some interviews were tape-recorded in Tibetan and later translated and transcribed, others were translated into English during the interview. Interviews with English-speaking participants were typed directly into a computer data base. An application for a research visa for access to the National Archives in New Delhi, India, was successful. However, the application took nearly eighteen months to process and arrived too late for me to make use of the opportunity.

Summary:

With the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet in 1912 the British govemment saw an opportunity to consolidate their influence in Tibet and re-establish Tibet as a buffer zone. The declaration of Tibetan independence inspired and facilitated a programme of development by the 13th Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama intended to initiate changes, political as well as social, which were necessary if his country was to remain independent. The revived problem of a Russian 'menace' in Central Asia was the primary reason for London to exert pressure on China to attend a conference at Simla in 1914. During the conference the British developed a comprehensive programme to revise the status of Tibet.

The Anglo-Tibetan Simla Agreement, in effect, proved to be an unequal bargain. In return for India's frontier security, the Tibetans were promised diplomatic and military support in their stmggle with China. From the viewpoint of the Tibetans, the 1914 Anglo-Tibetan agreement identified Britain as 'Tibet's Protector'. Yet, in spite VI of all the discussion on the status of Tibet, the notion of concluding some form of protectorate agreement with the Lhasa govemment was never contemplated. Instead, Britain proclaimed Chinese 'suzerainty' over an 'autonomous' Tibet. The recognition of Chinese suzerainty was to safeguard British commercial interest in China and the support of Tibetan autonomy was to ensure security of India's northern frontier.

This provided Britain with informal control of Tibet without involving the granting of responsible govemment and, at the same time, allowed Britain to continue her stationary economic imperialism in China. 1914 ushered in the Great War, which transformed global politics. During the war years Britain was not prepared to, nor in a position to give, active military assistance to Tibet and the opportunity for building a close relationship with an autonomous Tibet diminished. Taking up arms against China for the sake of Tibetan independence was never a consideration. The Dalai Lama considered that Britain had made a commitment to support and protect Tibet by signing the Anglo-Tibetan Agreement. By 1918 he was very disillusioned.

The question at issue by the end of the war was whether Britain was in a position to offer any form of diplomatic assistance or protection to Tibet. While China was deemed at the commencement of the First World War not to be a threat to Tibet, the war emphasised the increased danger of a China controlled by Japan. It soon became clear that Japan would attempt to take advantage of the war to expand her influence on the mainland of Asia. Despite this ominous situation, it seemed that pre-war circumstances were reviving in which British pressure would eventually overcome obstinate Chinese resistance, and an agreement on Tibet's status would be achieved. The world, however, was a different place after 1918. During the First World War and the period of post-war settlement British interests in China had radically to be redefined. Altering intemational economic patterns, changing imperial priorities, rising nationalism in the Far East, and the growth of new ideologies all had repercussions. The predominant theme in Anglo-Tibetan relations during the next few years was Britain's attempt to procure Chinese participation in renewed negotiations over Tibet and Peking's constant refusal, under an assortment of excuses, to oblige.

The British govemment's response to this rejection on the part of the Chinese govemment was to send a mission to Lhasa. The sending of a mission to Lhasa and the eventual agreement to supply arms and aid to Tibet were viewed at the time as manifesting a new determination in British policy. Its principal result was supposedly to demonstrate that the British govemment intended to treat Tibetan autonomy as a reality by strengthening Tibet's ability to defend Vll itself and by helping to develop the country's resources. Bell's mission to Lhasa, in reality, was a diplomatic bluff to coerce China into resuming negotiations, a bluff which failed. Further indefinite delay, coupled with a continuance of the policy of self-denial, would have involved the risk of the Chinese regaining control over Tibet, as had happened in 1910.

The British feared that the Tibetan govemment would conclude an independent treaty with China. Policy makers were faced with the choice of continuing to work for a settlement on existing lines, and mnning that risk, or of taking other measures to protect British interests by adopting a new and more liberal policy towards the Tibetans, which would entail the eventual opening of Tibet and the development of its resources under British auspices. It appeared that Tibet was being drawn more firmly under the umbrella of British influence. With British support, the 1920s seemed to promise a transformation of Tibet: a breaking away from old traditions and a move towards the radimentary development of technological, economic and military infrastmctures which would enable Tibet to become a self-sustaining independent state. Both Charles Bell, Political Officer, Sikkim, and the Government of India wanted a non-interference policy. At the same time they wanted Britain to help develop Tibet in a way that would enable the country to retain its independence but also serve British interests.

The eventual decision to provide military assistance and aid symbolised not a new tenacity of purpose but Britain's inability to intimidate China into accepting an ultimatum. The adoption of the so-called 'new and liberal' policy which followed Charles Bell's mission to Lhasa was little more than an attempt to induce the Chinese govemment to abandon their obstmctive attitude and conclude a settlement of the Tibetan question. The British hoped that the spectacle of Tibet's adoption of a policy of selfdevelopment would coerce the Peking government into submission. In retrospect, however, it can be seen that the support given to Tibet was inadequate and the direction which British policy took during the 1920s and 1930s resulted in the eventual loss of Tibet's independence. The conceptual basis of Britain's new policy was flawed: Britain wanted Tibet as a buffer but was not prepared to give the support necessary for it to remain independent. The source of Britain's impaired policy is manifest.

On the one hand, they were committed by a promise to the Lhasa govemment to support Tibet in upholding her practical autonomy, which was of importance to the security of India, and, on the other hand, Britain's alliance with China made it difficult to give effective material support to Tibet. What the British wanted was to create a balance. That is to say, give just enough support so that Tibet could protect India's Himalayan border without the British having V l l l to commit themselves to a major defensive initiative, while allowing the Tibetans, meanwhile, to pay for the honour of doing so. The intention was to convince the Chinese that Tibet was becoming self-sufficient. The ultimate objective was to get the Chinese to sign an agreement which would secure, for the British stability in Central Asia. British tactics were impotent and the Foreign Office adopted a 'wait-and-see' approach which dissolved into a 'dormancy' policy. The 1921 Washington Conference represented the crossroad in Anglo-Tibetan policy. Britain's wider economic and political considerations at this time altered Anglo- Tibetan relations.

Britain's Tibetan policy was impaired, as statesmen attempted to cope with the transition between pre-war commitments and post-war attitudes. The British government's post-war position made cooperation with the United States, or at least avoidance of American displeasure, the sine qua non of any successful policy. Britain's Tibetan policy during the 1920s and 1930s was to have no policy - to drift: a symbolic act which reflected the decline of British imperialism. The British found themselves on the defensive in the Far East and a desire to retain their trade position in China became dominant. Especially after the 1925 anti-British boycott in China, Britain followed a conciliatory policy and supported Chinese nationalism.

The implementation of Britain's new China policy during the late 1920s coincided with a period of intemal political turmoil in Tibet. The critical years for the Tibetan reformation were the 1920s, when the 13th Dalai Lama was attempting to strengthen and develop his nation. British govemment policy during this period limited the embryonic reforms and ultimately led to a weak and unstable Tibet. The Lhasa government exhibited a 'spirit of independence' but by 1925 the Dalai Lama was moving his allegiance away from Britain towards China. The Chinese Nationalist govemment took advantage of this tendency and adopted a 'forward' policy.

By 1933 British commercial interests in China made it necessary to subordinate Indian policy towards Tibet to the wider British approach to China. Britain withdrew from relations with Tibet because post-war intemational political and economic changes hastened the demise of the British Empire and required Britain to support Chinese nationalism. Britain had to choose either to support and protect Tibet or look after her own interests. Britain, not unnaturally, chose to do the latter.

British Relations With Tibet: till 1950, and after

British Relations With Tibet | Tibet.Dharmakara

Discussion of the official British position on Tibet and the issue of independence India

Relations up to 1950

When the British ruled India, their interest in Tibet was to exclude the influence of any other state that might disturb India's Himalayan frontier, while becoming involved in Tibet as little as possible themselves. The ways of pursuing these objectives varied at different times.

In the 19th century, Britain accepted the myth that Tibet was in a vague way part of the Chinese Empire, since this might help to exclude Russian influence. The Tibetans also used the myth to help them exclude influences from India that might threaten their culture and perhaps their integrity. In fact, China's influence in Tibet, which for a short time at the end of the 18th century was effective, vanished during the 19th century. In the 1880s and 1890s, British attempts to settle minor issues of trade and frontier alignment by treaties with China proved infructous, because the Tibetans would not recognise these treaties. Lord Curzon, as Viceroy of India, therefore tried to establish direct contact with the 13th Dalai Lama, who most unwisely refused to receive his correspondence. This deadlock became serious when Curzon believed unreliable information suggesting that Russia had obtained some influence in Lhasa. So the British Government reluctantly approved a small military expedition under Francis Younghusband, which fought its way to Lhasa in 1904.

This inauspicious start in fact established good relations with Tibet, which were subsequently maintained. The Lhasa Convention of 1904 settled many outstanding issues. But a new Liberal Government in London went full circle in 1906, influenced partly by dislike of Curzon's imperialism and partly by moves then afoot, prompted by fear of Germany, for the formation of an entente between France, Britain and Russia. The Lhasa Convention was re-negotiated with China in 1906, and in 1907 an Anglo-Russian agreement, covering Persia and Afghanistan as well as Tibet, provided that both parties would deal with Tibet only through China.

In the vacuum thus created, the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1906, and the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1910. The Chinese then started to infiltrate into Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and the tribal areas to the north of Assam. This set alarm bells ringing in Simla and London: what seemed to be needed was a buffer state against China as well as Russia. This was achieved when the Chinese emperor was deposed in 1911, thus breaking the personal link between the Dalai Lama and the Manchu Dynasty; when the Chinese troops in Tibet mutinied and were evacuated through India; and when the Dalai Lama, back in Lhasa, declared Tibet's independence in 1912.

At a conference in Simla in 1914, British, Chinese and Tibetan representatives negotiated the Simla Convention, providing for Tibetan autonomy with Chinese suzerainty, and a complicated and unsatisfactory arrangement about the Sino-Tibetan boundary. The Chinese withheld acceptance of this convention. They were accordingly told that Britain and Tibet would regard it as binding between themselves but that China would have no rights under it. In addition, agreements were concluded at Simla between Britain and Tibet (the Chinese being neither consulted nor informed) on trade and a definition of the frontier between India and Tibet in the tribal territory to the north of Assam (the MacMahon Line).

These arrangements were in breach of the Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907, and a release to cover them was sought from Russia. This difficulty disappeared when, in 1917, the Communist Government in Russia repudiated all the international engagements of the tsars, and when, in 1921, the 1907 Treaty was cancelled by agreement.

From 1910 onwards, the British Government treated Tibet as a de facto independent state with which treaty relations existed. From 1921 onwards, they were periodically represented by a diplomatic officer at Lhasa, and were permanently so represented from the early-1930s. In 1920, after a futile attempt to settle Tibetan issues with China, Curzon, then Foreign Secretary, told the Chinese Government that since 1912 Britain had treated Tibet as de facto independent, and would continue to do so. Britain was, however, ready to recognise China's suzerainty over Tibet, provided that China accepted Tibet's autonomy. This the Chinese never did, and so the offer to recognise China's suzerainty remained contingent. Nor did the British regard the concept of suzerainty as limiting Tibet's ability to conduct her own external relations, or as more than a sop for saving China's face. The Tibetans never accepted the idea of suzerainty after China rejected the Simla Convention.

In 1943, the Chinese foreign minister asked Anthony Eden how Britain regarded the status of Tibet, and was given an answer similar to Curzon's statement of 1921: that the British Government "had always been prepared to recognise Chinese suzerainty over Tibet, but only on the understanding that Tibet is regarded as autonomous" (Memorandum from Sir Anthony Eden to the Chinese foreign minister, T.V. Soong, 05/08/43, FO371/93001).

In the same year, the British Embassy in Washington wrote to the US Government, stating: "The Government of India has always held that Tibet is a separate country in the full enjoyment of local autonomy, entitled to exchange diplomatic representatives with other powers. The relationship between Tibet and China is not a matter that can be decided unilaterally by China, but one on which Tibet is entitled to negotiate, and on which she can, if necessary, count on the diplomatic support of the British Government along the lines shown above."

With the transfer of power to the two new dominions of India and Pakistan, Britain's direct political concern with Tibet ended, along with the cessation of her responsibility for the defence of India. One might, however, expect any British Government to be concerned on general historical grounds at China's military seizure of Tibet in 1950, and her brutal treatment of the Tibetan people for four decades.

' Note: Written by Sir Algemon Rumbold, President of the Tibet Society of the UK 1977- 1988, for TSG UK.

All attempts to discuss Tibet are bedevilled by the Chinese redefinition of the country's borders since 1949. Here the term Tibet is used to refer to the three original provinces of U'Tsang, Kham and Amdo (sometimes called Greater Tibet). When the Chinese refer to Tibet they invariably mean the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) which includes only one province, U'Tsang (the TAR was formally inaugurated in 1965). In 1949 the other two provinces, Amdo and Kham, were renamed by the Chinese as parts of China proper and became the province of Qinghai and parts of Sichuan, Gansu and Yunnan provinces.

Later British policy

The current British position on Tibet is described in a policy statement of January 1994, which begins: "Successive British Governments have consistently regarded Tibet as autonomous, although we recognise the special position of the Chinese there" ('Government Policy on Tibet', a Statement from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Jan 1994). The statement continues: "Independence for Tibet is not a realistic option. Tibet has never been internationally recognised as an independent state, and no state regards Tibet as independent" ('Government Policy on Tibet').

Britain did officially regard Tibet as being de facto independent for much of the first half of the 20th century -from a Tibetan declaration of independence in 1912 until the Chinese invasion and occupation of 1949-50. British representatives were stationed in Tibet from 1904 to 1947 to liaise with the Tibetan Government.

The Government does not feel that the Dalai Lama has a political role, and his visits to Britain are held to have been purely of a "private and religious" nature. Moreover, the British authorities have declared they "have no formal dealings with the Dalai Lama's self proclaimed Government-in-Exile, which is not recognised by any government." (`Government Policy on Tibet').

This information was compiled by Tibet Support Group, UK 9 Islington Green London N1 2XH England.

Additional material was added by the Australia Tibet Council PO Box 1236 Potts Point NSW 2011 Australia.

See also

Anglo-Chinese Conventions of 1890 and 1893

Convention between the United Kingdom and China respecting Tibet, 1906