Bahawalpur

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Bahawalpur

March 30, 2008

EXCERPT: The abode of light

The book focuses on the magnificent buildings of great historical and architectural value in Bahawalpur, the former princely state.

The beginnings of what became the state of Bahawalpur in AD 1727, lie to its south in the Cholistan Desert. In fact, Cholistan was not always desert. The long-extinct Hakra River — the lost river of the Indian Desert — was its lifeline between 4000 and 1000 BC, allowing a civilisation similar to the early Harappan phase of the Indus Valley civilisation to flourish until the river turned course and disappeared. The Aryan invaders who periodically swept through the Indus Valley between 1800 and 800 BC found little to stay for, instead moving east towards the Ganges. Cholistan remained little more than a temporary halting place for invading armies from the West, although, by the end of the fourth century BC, the Macedonian invader, Alexander the Great was sufficiently captivated by Uch to rename it ‘Alexandria Uch’ and make camp there for a fortnight.

Rulers and invading armies came and went, some leaving behind architectural traces. Nearly a century before Christ, the Kushanas, under the great warrior-turned-Buddhist king Kanishka, built Buddhist monasteries at Sui Vihar and Pattan Minara in what is now Rahim Yar Khan; the remains of both monasteries still stand. Perhaps the earliest record of military architecture in this region dates back to the early sixth century AD to the Rai dynasty, whose scions left three forts in Cholistan. The Arab invasion of Sindh in AD 712, and the subsequent establishment of first Umayyad and then Abbasid rule from the port of Dibul to Multan, met with fierce resistance in Cholistan. A number of graves, known as ‘Sahabi’s graves’, dot the Hakra riverbed at Marot, Derawar, Mubarak Pur, Musafir Khana, Ahmadpur, and Bahawalpur.

With the decline of the Arab khilafat (caliphate) in AD 817, the territories of Multan and what is now Bahawalpur became independent under the control of Abdul Tallat-ul-Munabba Qureshi. The Cholistan region took on a more prominent role — Rahim Yar Khan became southern Punjab’s cultural hub and, later, Uch became a centre of political activity in response to the expansionist policies of the Ghauri Sultanate in Delhi during the thirteenth century AD. The ‘Slave King’ rulers that followed the Ghauris, such as Shahab-ud-Din Ghauri, Qutub-ud-Din Aibak, and Nasir-ud-Din Qabacha turned their attention to Uch, the latter making it the seat of his government. With the Mongol incursions into India in the 13th century AD, the fortunes of the Bahawalpur area took on an increasingly violent turn in parallel with the rest of India. In AD 1437, the Langah Afghans broke out in rebellion, their leader, Shah Yusuf Qureshi, appointing himself ruler of Uch and Multan in AD 1443. While the Timurid prince Babur set his sights determinedly on the throne of Delhi in AD 1521, Shah Hussain Arghun of Sindh marched on Derawar in AD 1524, capturing the garrison after a bloody assault in which its defenders were killed. The area continued to pass hands from one dynasty to the next, until it finally fell under Mughal rule.

The death of the Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb Alamgir, in AD 1707 brought with it an end to civilised rule in the present Bahawalpur territories. Cholistan was split among bickering warlords, plummeting into what was probably the darkest period in its history. Even then, Uch — by now a widely acclaimed seat of Muslim learning — retained much of its glory, piquing the interest of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.

Some four generations after the fall of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad in the thirteenth century AD and its subsequent shift to Egypt, Sultan Ahmad Abbasi II left for India, making his way to Makran between AD 1366 and 1370. There, he was ceded territory in Sindh and the Bahawalpur area by Raja Dhoring after defeating the latter in battle. Sultan Ahmad Abbasi was succeeded by various Abbasi ameers until Ameer Mehdi Khan Abbasi, whose death split the clan into two, the Daudpotras and the Kalhoras. The Daudpotras were descendants of Daud Khan, Ameer Mehdi’s brother; and the Kalhoras, descendants of Ibrahim Khan, Ameer Mehdi’s son.

The Daudpotra Abbasis, under Bahadar Khan Abbasi, founded the city of Shikarpur in 1617. He was succeeded by Ameer Mubarak Khan Abbasi I in 1702, who was followed by Ameer Sadiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi I. The bitter rivalry between the Daudpotras and the Kalhoras had now reached its peak; to dispel the tension, Sadiq Muhammad Khan relocated to the area that is now Bahawalpur and curried favour with the Mughal governor of Multan, who granted him land in Chaudri, now a village in present-day Khanpur. As his power grew, he shifted his capital from Chaudri to Derawar. His heir, Ameer Bahawal Khan Abbasi I, ascended the throne in 1746, and in 1747, designed a new capital city and gave it his name: Bahawalpur. The city was stunningly modern for its time, built in an oval shape and designed with wide streets, open parks, elegant villas, and royal residences. In all, 13 Abbasi ameers ruled over the state of Bahawalpur from 1702 to 1954, a period of more than 250 years, during which time it gradually expanded into the second-largest Muslim state in the subcontinent.

The golden era of the Abbasids in Bahawalpur is best characterised by its architecture — all that remains of the period today. Its garrisons, palaces, tombs, fortresses, libraries, universities, hospitals, and irrigation projects ushered in an era of royal, authoritarian, but welfare-oriented governance. As the rulers of a state that came into existence by conquest, the Mughals, and later the British Raj, held the Abbasi rulers in great esteem.

In 1947, the state of Bahawalpur was one of the notable Muslim states in undivided India with a Muslim ruler and a predominantly Muslim population. With the independence of India and its partition into India and Pakistan, Bahawalpur’s last ruler, Nawab Al-Haj General Sir Sadiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi V, chose to cede to Pakistan. The first guard of honour presented to M.A. Jinnah, the Quaid-i-Azam, on becoming governor-general of Pakistan, was by a contingent of the Bahawalpur State Forces. The ameer of Bahawalpur also provided financial assistance to his newly independent country. In 1954, the state of Bahawalpur was merged with the province of West Pakistan under the One-Unit Scheme. The last ruler of Bahawalpur, Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi V, died in London in 1966. His body was brought back to Pakistan and buried in the Royal Graveyard at Derawar Fort. The Abbasid dynasty of Bahawalpur had come to the end of its line.

- * * * *

Nur Mahal stands amidst rolling emerald green lawns. After the Sadiqgarh Palace, it is the largest and most beautiful of the Abbasid palaces. It was commissioned by the governor of the Punjab as a residence for Ameer Sadiq Muhammad Khan IV, popularly known as the Shah Jahan of Bahawalpur for his passion for constructing beautiful buildings. It was designed by Muhammad Husain, an architect from the Chief Engineer’s Office in Lahore, and its construction supervised by a state engineer named Heenan. Its foundation stone was laid by Ameer Sadiq Muhammad Khan IV in 1872; a jar full of state coins and an inscription bearing the date of the foundation laying were buried in the foundation. The palace was completed in 1875 at a total cost of 1.2 million rupees. Ameer Sadiq Muhammad Khan IV resided in the palace for a short time, but soon shifted out, possibly because of his apprehensions concerning its proximity to the graveyard of Maluk Shah. Later on, the palace was reserved solely for court functions — such as the durbar held by Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Agerton, the governor of the Punjab, on 25 November, 1879, installing Ameer Sadiq IV as the ruler of Bahawalpur in the palace — or for lodging guests of high rank.

One of the most important events to be held at the Nur Mahal was the coronation of Ameer Muhammad Bahawal Khan V on 12 November 1903. India’s viceroy and governor-general, Lord Curzon, was also present for the occasion. Many prominent people from all over India attended the coronation, including more than a 100 foreign officials. After 1947, the palace continued to host visiting dignitaries, and was used as a state guesthouse by the second prime minister of Pakistan, Khawaja Nazim-ud-Din, who visited Bahawalpur in 1955, before the state seceded formally to Pakistan. In 1976, the palace was initially rented out, and later sold, to the Pakistan Army.

Rectangular in plan, the Nur Mahal consists of square, double-storey rooms at each of its four corners, crowned with square domes. The central dome is octagonal, arching towards the centre. Viewed from the front, it stands out as impressively with white pillars and domes that provide a contrast against the brick construction. The porch has a unique triangular face and bears the official state emblem.

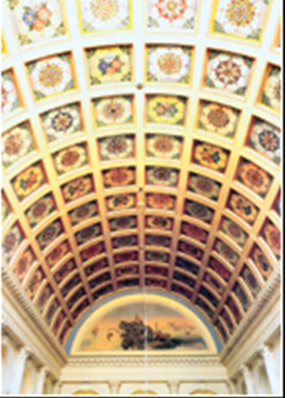

The main central hall is rectangular in plan and oriented in a north-south direction. It has a ghulam gardish (gallery) on three sides separated by pairs of columns erected below the arched openings. The main entrance to the hall is through the front porch, where a flying staircase leads inside the building. The floor of the main hall has a delicate finish of colourful, imported mosaic glazed tiles arranged in geometric patterns. The floor currently shows signs of damage at places. The hall has a barrel-shaped ceiling that is delineated by three types of intricate floral motifs, each occupying a square space in diagonal rows. A painting at one end of the ceiling depicts a river scene in bright chemical colours. Receding panels in the hanging gallery’s walls display portraits of past ameers, and grand pianos and large mirrors give a palpably period feel to the palace.

The palace veranda is built in a series of arcades, and has a trabeated roof. The roofs of each set of three bedrooms, corridors, and side halls are laid in reinforced brickwork. The roof of the corridors is also curved, and provided with ventilation ducts. In fact, the palace is well provided for as far as ventilation is concerned, which helps keep even the high summer temperatures tolerable. The ventilation system comprises two tunnels below the main corridors in the eastern and western wings. Laid in a north-south direction, these tunnels draw in cooler air from ground level and push it up through ducts onto the floors of the rooms above. The ducts are covered by cast-iron frames, through which the warm air is then automatically pushed out through the roof.

The palace was handed over to the Pakistan Army in a very poor state, and was subsequently renovated, with special emphasis given to conserving the original character of the building while enhancing its outstanding features. As a result of this renovation, the palace is now well worth visiting, especially at night when it is beautifully illuminated.

________________________________________

Excerpted with permission from

Sights in the sand of Cholistan

Edited By Major-General Shujaat Zamir Dar

Oxford University Press, Karachi

134pp. Rs995

Major General Shujaat Zamir Dar is involved in the preservation of historical buildings such as the Robert Sandeman residence in Zhob

Bahawalpur II

Rehabilitation plan knocks at Bahawalpur’s old gates

By Our Correspondent

BAHAWALPUR, June 3: The district government plans to rehabilitate all the five historic gates of the walled city, according to District Coordination Officer (DCO) Muhammad Mushtaq Ahmed.

The DCO told reporters here on Tuesday that the government would rebuild the old gates of the defunct Bahawalpur state, which would beautify the entrance points of the city.

The DCO said the clock towers of the century-old Sadiq Dane High School and the swimming pool of the Dring Stadium would also be rebuilt.

He said a ring road of about 34 kilometres estimated to costRs400 million, an overhead bridge on the Multan Road railway crossing and an underpass on the main Lahore-Karachi railway track near the Bahawalpur railway station were planned for the convenience of people.

He added that the projects would be approved by the government soon and parliamentarians were trying to get funds from the government.

The district coordination officer said an operation against encroachments in the city would be launched from June 10.

He said the government had taken action against over 100 teachers and doctors for dereliction of duty.

He said the on-going projects of the general bus stand, the Noor Mahal Road, Astroturf at the stadium and the Yazman-Hasilpur Road were likely to be completed by June 30.

He said the Friday bazaars would be revived in the city. He added that the special audit of the local councils would be done impartially.