Central Bureau of Investigation: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

CBI investigations: who can order?

HC can order CBI probe

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

HC can order CBI probe: SC

Swati Deshpande | TNN

Mumbai: A five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court headed by the Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan, on Wednesday adjudged that the country’s high courts can order a CBI probe into a case without the assent of a state government, while also cautioning that such powers should be used sparingly, and only in matters of national or international importance.

The SC was hearing the West Bengal government’s petition challenging the Calcutta high court order of a CBI probe into the Midnapore firing in which 14 Trinamool Congres workers were killed. The WB government argued that law and order was a state subject and that a CBI probe without the state’s nod would be a ‘‘destruction of the federal character of the Constitution’’. West Bengal was the main petitioner along with some southern states.

But, taking a stand based on the ‘‘higher principle of constitutional law’’, attorney general Goolam Vahanvati argued that the powers of the high courts and the Supreme Court under Articles 226 and 32 were coupled with a strong obligation to prevent injustice in sensitive cases and to protect the fundamental rights of citizens. The SC bench agreed with him, and dismissed the petition. Until now, the CBI conducted probe in any state only with prior consent of the concerned government under the provisions of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act.

The five-judge Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices R V Raveendran, D K Jain, P Sathasivam and J M Panchal agreed unanimously with Vahanvati but said the power must be exercised sparingly in ‘‘exceptional and extraordinary circumstances.’’ Otherwise, the CBI will be flooded with such directions in routine cases, the bench said.

Directors of CBI

2017-...: Alok Verma

Appointment of the CBI Chief, Jan 20 2017: The Times of India

Govt appoints Delhi top cop as new CBI chief

Alok Verma Gets PM & CJI's Nod, Kharge Dissents

The government has approved the appointment of Delhi Police commissioner Alok Verma as the new CBI chief in keeping with the recommendation of the selection committee.

The proceedings of the three-member collegium comprising PM Narendra Modi, Chief Justice of India J S Khehar and leader of Congress in Lok Sabha Mallikarjun Kharge, proposed the appointment by a majority decision.

Kharge gave a dissenting note, stating that the selection should be on the basis of both seniority and merit. It is understood that he had pitched for the candidature of R K Dutta, currently special secretary in the home ministry . Kharge reportedly gave his dissent note on selecting Verma citing that he had no experience of having served in CBI and he also had very little vigilance experience.

The PM and the CJI, however, felt that Verma was well suited for the job and his seniority should be taken into account.Verma will assume charge at a time when the agency is being accused by political parties of motivated probes in the context of cases against Trinamool and AAP leaders.

The decision comes ahead of the hearing in Supreme Court on Friday on a plea filed by an NGO challenging the appointment of Rakesh Asthana as acting director of the CBI after the retirement of Anil Sinha.

Official sources said Verma, a1979 batch IPS officer from the Arunachal Pradesh-Goa-Mizoram and Union Territories cadre, has been appointed CBI director for a period of two years by the Appointments Committee of Cabinet from the date he assumes office. Verma, 59, was due to retire from service in July and will now have a fixed tenure of two years. He had worked in various positions in Delhi Police, Andaman-Nicobar Islands, Puducherry , Mizoram and the Intelligence Bureau. Verma, who took charge as Delhi police chief in February last year, is likely to join in a couple of days. The CBI director's post has been lying vacant since Anil Sinha retired in the first week of December. Soon after, Asthana, a 1984 batch IPS officer from Gujarat cadre, was named interim director.

He took charge of Delhi Police from B S Bassi after relinquishing charge as director general of Tihar Jail. Verma, who will be the 27th director of CBI, has not worked in the agency before. Verma takes over at a time when the CBI is probing several crucial cases including the Rs 3,767 crore VVIP chopper scam, in which former IAF chief S P Tyagi was arrested last month. Several defence scandals, the Embraer deal, coal and 2G scams, chit fund cases, Vyapam scam, NRHM scam and non-performing assets of public sector banks are other cases being probed by the agency .

While deciding Verma's name, the collegium had also discussed the names of three other strong contenders R K Dutta, Maharashtra DGP Satish Mathur and ITBP director general Krishna Chaudhary .

Verma's appointment will also leave Delhi police headless and the government will have to soon choose the next commissioner. Two senior IPS officers Dharmendra Kumar and Deepak Misra -are in line for the post.

Directors investigated by CBI

A P Singh

Neeraj Chauhan, CBI books one of its ex-chiefs for corruption, Feb 21 2017: The Times of India

AP Singh Faces Probe In Moin Qureshi Case

The Central Bureau of Investigation has booked its former director, A P Singh, as an “accused“ under the Prevention of Corruption Act to probe his association with meat exporter Moin Qureshi, allegedly a middleman for senior officers and politicians.

The agency conducted raids at Singh's residence in Defence Colony , the premises of Moin Qureshi and another key accused and Hyderabad-based businessman Pradeep Koneru and others in Delhi, Ghaziabad, Chennai and Hyderabad. It is the first time that CBI has on its own initiated a probe against its ex-director in a corruption case.CBI's probe against another former chief of the agency, Ranjit Sinha, who succeeded Singh, was at the instance of the Supreme Court. Among other things, CBI has based its case against Singh on BlackBerry messages exchanged. Many messages mentioned in the FIR refer to amounts Qureshi allegedly deposited in the accounts of Singh's daughter, Ragini Behrar, who was in London.The alleged exchanges have Qureshi regretting a dip in transfers during what he called a “lean season in meat business“ and Singh's daughter thanking him for making her “so rich“.

In another message allegedly sent by BBM to Qureshi, who was identified by the Enforcement Directorate as a middleman for certain public officials, Singh purportedly asked him to get a packet delivered at 37, Slaidburn St, presumably an address in London. Another BBM message cited in the FIR has Qureshi seeking help for a “family friend“, a former chairman of a public sector bank who was being investigated in agraft case. Singh, in his reply to Qureshi on BBM, said that the chargesheet had already been filed in the case and Qureshi's family friend could get help only from the court.

The exchanges between the two continued after Singh had left CBI and one of the alleged exchanges on BBM show Qureshi trying to help an aviation logistics firm for which he had planned to approach two senior politicians. Singh responded by suggesting that Qureshi approach someone else, a person whose surname matched that of a powerful minister.

A 1974 batch IPS officer, Singh headed the probe agency between November 30, 2010 and November 30, 2012, when the Congress was in power.His tenure saw the arrest of former telecom minister A Raja and several corporate bigwigs in connection with the 2G spectrum allocation scam, former Indian Olympics Association chief Suresh Kalmadi in the 2010 Commonwealth Games scam and the Aarushi-Hemraj murder probe. He was appointed a member of the Union Public Service Commission by the UPA government. However, a tax evasion probe by the income tax department against Qureshi brought out their close links. The probe saw the Modi government putting his appointment in the deep freezer, leading Singh to decline the appointment.

In a report filed in SC in October 2014, on the basis of the I-T department probe, attorney general Mukul Rohatgi had said, “The report reveals an astonishing state of affairs (that is) wholly unbecoming and revealing the shocking conduct of a former CBI director, now a member of the UPSC. He was in regular touch with Qureshi and there were BBM exchanges between them on a daily basis and that too in code language.Many of the messages clearly revealed plans to save the accused in many cases.“

In 2016, Qureshi had managed to leave the country without informing any authority despite having a lookout circular against him. He, however, came back in a few days.

International ambit

2016

CBI director Anil Sinha said in 2016 that 392 of its criminal investigations, which have international angles to them, are pending in 66 countries.

The central anti-corruption agency has many investigations where it needs information from several countries including 2G scam, AgustaWestland scam, the defence scandal related to Embraer and India deal. CBI is India’s nodal agency for the transnational organised crime, Interpol, anti-corruption and bank frauds. (The Times of India)

‘Stay orders’ cannot be issued

138 graft cases stalled due to SC stays

138 graft cases stalled due to SC stays: CBI, August 1, 2017: The Times of India

The CBI told the Supreme Court that despite a statutory ban on higher courts staying trial in corruption cases, the apex court's stay on 45 appeals had resulted in trials in 138 cases under Prevention of Corruption Act getting stalled.

Solicitor general Ranjit Kumar informed a bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justice D Y Chandrachud that some of these appeals were pending in the SC for the last 15 years and CBI investigating officers now feared that any further delay in restarting the trials would result in losing evidence.

Lapse of time has a serious impact on producing evi dence through witnesses in criminal trials, especially in corruption cases, the SG said and requested the court for vacation of stay granted on the petitions filed by various accused persons from across the country who were prosecuted under PC Act by the CBI. The bench agreed to list the appeals for hearing on August 7.

The SG said stays in graft cases were granted despite a statutory ban under Section 19(3)(c) of the PC Act, which provides, “No court shall stay the proceedings under this Act on any other ground and no court shall exercise the powers of revision in relation to any interlocutory order passed in any inquiry, trial, appeal or other proceedings.“

Success rate

70% conviction of tainted officials: 2006-16

4,054 Cases In Which Govt Staff Found Guilty In Last Decade

Nearly seven out of every 10 corruption-related cases investigated by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) ended in conviction of government officials in the last decade, a record that justifies the dread that the agency strikes among unscrupulous officials.

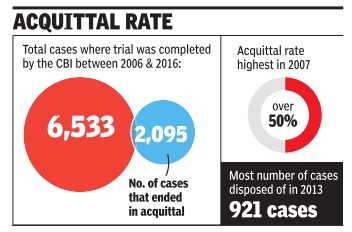

Since 2006, CBI probed over 7,000 cases, of which trial has been completed in 6,533. About 4,054 cases (68%) ended in conviction of the accused under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, while 2,095 (32%) ended in acquittal.

The relatively high conviction rate counters the popular belief that trials in India are often delayed and officials, along with the influential, usually avoid jail time.

The analysis by public information website Factly .com is based on data shared by the government in Lok Sabha. “Given Indian conditions, 68% conviction is fairly decent. The major flaw is in the judicial system which is full of delays, which in turn allows influencing witnesses, said Shailesh Gandhi, former information commissioner.

Of the 7,000 corruption-related cases probed and disposed of between 2006 and June 2016, some 3,615 ended in prosecution, 2,178 ended in prosecution as well as regular de partmental action (RDA) while 636 cases were subject to only RDA. Another 671 cases were closed without action.

While CBI investigates select cases, national data up to 2015 showed that 13,585 corruption cases were being investigated, mostly relating to bribery and criminal misconduct. Some 29,206 corruption cases were pending trial while the accused were acquitted or discharged in 1,549 cases in 2015.

CBI completed investigations in the highest number of cases in 2008 followed by 2007. The least number of cases were investigated and disposed of in 2010, the year when the 2G and Commonwealth Games scams held national attention.

On an average, 9.3% of the cases ended in closure without any action.

In cases where trial has been completed, acquittal rate was highest in 2007 at over 50%. Most number of cases were disposed of in 2013 (921), followed by 865 in 2012. The least number of cases were disposed of in 2008 (369).

Data from the National Crime Records Bureau show an increase of 5% in corruption cases in 2015 (5,867) compared with 2014 (5,577).

Factly .com's Rakesh Dubbudu noted that getting sanction for prosecution of a government official continued to be an issue.

The CBI: jurisdiction, type of work, importance

LEARNING WITH THE TIMES - CBI can take suo motu action in graft cases under PCA Why did we need the CBI?

The significant increase in the British government's expendi ture in the early stages of the Second World War resulted in profiteering by corrupt businessmen and government officials. Since the local police found it difficult to investigate these cases, the British government felt the need for a special force. The Special Police Establishment (SPE) with mandate to investigate cases of bribery and corruption in transactions related to war, was formed under the War department in 1941.In the post-war years, the need for a central investigating agency was felt and Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act was brought into force in 1946, which also shifted its superintendence to the home department. Later, the DSPE was re-christened Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in 1963. Even today , the jurisdiction of CBI is defined by DSPE Act 1946.

What kind of cases does the CBI investigate?

CBI was primarily supposed to investigate cases involving central government employees or the interests of the central government, and crime on the high sea and airlines, as per the DSPE Act, 1946. It was vested with power to investigate cases of breach of central laws related to export-import, foreign exchange, passports and so on. It also investigated serious cases of fraud, cheating and embezzlement relating to Public Joint Stock Companies and other cases of a serious nature, when committed by organised gangs operating in several states. In addition, it collected intelligence about corruption in public services as well as in projects and undertakings in the public sector.

When did the CBI start investigating conventional crime?

Initially an anti-corruption probe agency , in due course of time the CBI started receiving requests from various quarters of government and judiciary to investigate conventional crime and other specific cases like the Bhagalpur blindings, Bhopal gas tragedy and so on. Since early 1980s, constitutional courts also started referring cases to CBI for investigation and enquiry . In 1987 as its role expanded, it was divided into two sections -an anti-corruption division and the special crimes division, the latter dealing with conventional crimes and economic offences. Apart from this, special cells have often been created to investigate high-profile cases like Rajiv Gandhi's assassination, Ba bri Masjid demolition and so on.

What is CBI's jurisdiction?

CBI derives its power from section 2 of the DSPE Act 1946 to investigate offences in Union Territories only. However, the jurisdiction can be extended by the Centre to other areas, including Railways and also state governments, with their consent.CBI is authorised to probe only those cases notified by the Centre. Anyone can make a complaint regarding corrup tion in the central government, PSUs and nationalised banks; CBI can also take suo motu action in cases under Prevention of Corruption Act. It can investigate criminal cases if a state requests the Centre for CBI's help, or when SC or an HC direct CBI to investigate a crime.