Lucknow: K-O

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

The Kaiser Bagh Palaces

Wajid Ali Shah, the last King of Oudh, who came to the throne in 1847, started to build the Kaiser Bagh Palaces the year after his accession, intending to make them the eighth wonder of the world. The buildings were completed in 1850. Rumour had it that their cost exceeded eighty lakhs and that the area they covered was greater than that of the Tuileries and the Louvre put together. So eager was the King for quantity that, as with most of his inspirations, quality was forgotten. All that now remains of his enormous conception are buildings on three sides of a quadrangle.

Somewhere near the tennis courts of the Oudh Gymkhana Club stood the Jilankhana, a triumphal gateway whence royal processions wound their way through dense crowds of applauding citizens. Another gateway led to the Chini Bagh ornamented with Chinese vases and decorations, the Lakhi Gate which as its name implies cost a lakh of rupees, the Kilo Khana, the Hazrat Bagh, the Chandiwala Baradari with its floor of polished silver, and many others now only names instead of grandiose buildings.

Wajid Ali Shah was fond of singing and dancing. He even dressed in female garments himself and danced before the ladies of the harem. Every year he acted in a play—always the same one.

One of his wives was chosen to represent Ghyzalah, and as she was beautiful, the honour of representing her was eagerly sought in the harem ; others were dressed as peris with silver wings. Another represented Rajah Indra, the king of fairies of Hindu mythology Others were dressed up as evil genii and their attendants with black ornaments, black wings and black faces. None wished to act these last parts, but at the expression of the King’s wishes none could refuse.

The play was enacted in the silver baradari of the Kaiser Bagh palace in Lucknow, which was divided for the purpose into three compartments. One of these was fitted up as Rajah Indra’s court, the pillars covered with silver and rich ornaments attached to the ceiling and walls. At night it was a blaze of light with chandeliers and mirrors. In the centre stood Indra’s throne, and there the lady representing him sat in state clothes in rich apparel and attended by crowds of peris.

Without, fountains of scented water played. The seats of the garden were gilded or silvered over to shine amid the flowers and fountains lit up during the day by the sun’s rays and at night by a myriad lamps. For ten days and nights this pageant continued. Another room was fitted up as a royal bedroom. A golden bedstead, a rich counterpane, a magnificent carpet, and golden furniture framed the beautiful Ghyzalah, her delicate limbs in gauze or muslin edged with golden tissue, her black hair shining with gems. On the tenth day, the King danced for the entertainment of the multitude and insisted upon the queen and Khas Mehal and other leading ladies of the court giving him presents of money.

The yellow buildings round the quadrangle are now the property of the Taluqdars of Oudh as town houses. Gateways on either side, bearing a resemblance to the crown surmounting La Martinière College, are ornamented with the royal fish badge. Massive doors studded with curious iron plaques swing on rusted hinges.

It is possible to walk for some distance along the flat roofs. The rooms within are long and not very lofty, with deep verandahs giving on to the central court. Many of the King’s most precious treasures (not to mention his harem numbering nearly four hundred, each of whom occupied a suite of rooms and had her own attendants) were housed in the Kaiser Bagh, and the mutineers made it one of their most formidable strongholds in 1857.

In the fighting at the Moti Mahal during the first relief the British troops were much harassed by fire from the Kaiser Bagh. The 78th Highlanders fought their way along the Hazratganj and suddenly found themselves on the flank of the enemy battery which was causing most of the trouble. The Highlanders made a rush to spike the guns before pressing on and joining the main column.

During the second relief musketry fire from the Kaiser Bagh again swept the ranks of the relieving troops. From November 20 to 22 the full force of British guns was turned on it. This was after the Residency had been evacuated by the women and children. By the 22nd three wide breaches had been made in the walls and the entire enemy resources were mustered at these points, for an assault was expected. Attention thus diverted from the Residency, shortly before mid-night the gallant little personnel of the Residency collected at the Bailey Guard gateway and silently filed out.

Early in March 1858 the enemy again fortified the Kaiser Bagh with three lines of entrenchments including the canal. On March 13, the Sikhs attached to the British force penetrated into an outlying court of the Kaiser Bagh. From the roofs of the houses they fired upon the men below, to drive them from the guns.

This so weakened the defences that Napier and Franks held a rapid consultation and decided to concentrate their entire strength upon the Kaiser Bagh. During this attack Captain L. S. Da Costa, 56th Native Infantry, was killed. He lies buried near Major Hodson in La Martinière Park. Franks’ column attacked from the enclosure of Sa’adat Ali Khan’s tomb and joined the main body of soldiers, sailors, Gurkhas and Sikhs in the courts of the palace. The bulk of the attack was broken but armed men found refuge in the buildings, and every palace became a fortress. From the green Venetian blinds closing the apertures which pierce the walls in double rows, a stream of bullets poured into the square, so that the marble pavement was stained with the blood of Sikh and Briton.

“Building after building was taken and bloodthirst revenge and greed for gold glutted the avarice of the Sikh and the British soldier. Rough hands tore away the silks, velvets, brocades, laces and gems accumulated by the lights of the Harem ; wrought silver plates were torn from the throne of some favourite mistress or queen ; the monuments of western and eastern art were broken to pieces, and fragments of rare China and of crystal vessels strewed the floors. When night put an end to the pillage, the palace of the Kaiser had become a ruined charnelhouse

The Khurshaed Munzil

Khurshaed Munzil means “House of the Sun.’ It was named by Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan after one of his favourite wives, Khurshaed Zadi, for whom he designed it. It was built between 1800 and 1810, and is a two-storeyed building having six towers at irregular intervals round it and four entrances which were originally drawbridges over the deep revetted moat. This is now empty of water but is believed to be in some way connected to the Gumti.

Some say that Sa’adat Ali Khan’s son, Ghazi-ud-Din, completed the house on his accession to the throne and that he added the moat and drawbridges. Ornamenting the outside of the house is a frieze of suns carved in stone. An unusual feature is an inside stair case, built thus instead of outside as usual, because the house was expressly designed for women in purdah.

When Oudh ceased to be an independent kingdom in 1856, the Khurshaed Munzil was occupied by the officers of the regiment quartered in Lawrence Terrace, and became known to fame as the 32nd Mess House. In 1857 it was taken possession of by the insurgents and was the scene of sharp fighting.

On July 7, Havelock started from Allahabad on the first relief expedition, and by September 25 his force was within a few hundred yards of the Residency. Musketry fire assailed them from the Khurshaed Munzil as their enemies contested every foot of the way. At that time there was a more or less open field of fire between the Kaiser Bagh and the rising ground upon which stands the Khurshaed Munzil except for the maze of lanes and low-walled courtyards covering the gardens where the statue of Queen Victoria now stands.

From 9 a.m. on November 17, Peel’s guns concentrated on Khurshaed Munzil and at about three in the afternoon, when the musketry fire from its defenders had diminished, Captain (afterwards Field-Marshal Viscount) Wolseley of the 90th Foot was ordered to lead an assault against it, his force consisting of a company of the 90th and detachments of the 53rd Foot and the 2nd Punjab Infantry.

The enemy failed to stand up against their concerted rush. Lieutenant (afterwards Field-Marshal Lord) Roberts closely supported by Sir David Baird and Captain Hopkins of the 53rd Foot made a dash for the narrow staircase of the turret nearest to the Kaiser Bagh, and planted there the standard of the 2nd Punjab Infantry. Twice was it shot down but the third time it resisted every effort to dislodge it and proclaimed to all and sundry the capture of the house.

By this time only four hundred yards separated the relieving force from the garrison. Outram and Have lock were determined to press on. Sir Colin Campbell was awaiting them on the sloping lawns of the Khurshaed Munzil. Hope Grant, an eye-witness of the incident, records “a cordial shaking of hands.” Just inside the main entrance to the Khurshaed Munzil stands a small pillar which bears the inscription: “It was here that Havelock, Outram and Sir Colin Campbell met on the 17th November, 1857.” J. Jones Barker painted a well known picture entitled “The Meeting of the Generals at the Relief of Lucknow.”

The original belongs to the Glasgow Municipality and a copy hangs in the museum at the Residency. Another writer describes the scene thus: “What a meeting was that ! The Iron Chief, Sir Colin, with the dust of battle still upon him, the good Sir James, and the dying Havelock. Meeting, too, while the walls of the palace where they stood were still reverberating with the din of battle—fit atmosphere for that reunion.

True knights, these three brave hearts! Each had imperilled his life to rescue the helpless, and one was soon to lay his down, worn out in their defence.” The possession of the Khurshaed Munzil was the keystone to the whole position, and when it was once in the hands of the relieving force the relief of the Residency was assured. Early the next year, when the British had withdrawn from their hard-won posts in Lucknow, the opposing force reoccupied them and their second line circled round the Khurshaed Munzil and the Moti Mahal.

On March 11, 1858, a British battery situated where the Colvin Institute now stands began to bombard the Khurshaed Munzil. Two days later it was recaptured for the last time. In 1876 the Lucknow Girls’ School, founded by Mrs. Abbott, moved from the Moti Mahal to the Khurshaed Munzil, and Government made over the building free of rent to the School authorities on condition that it should be returned if at any time the school were abolished.

The name of the school was changed to La Martinière Girls’ School because it was to enjoy some of the funds of General Martin’s trust. Spacious halls form class rooms and the drawing room on the ground floor. Above are dormitories, for some sixty pupils. Wide verandahs skirt the lofty-rooms. From each of the six turrets one has a fine view of the surrounding country. On one of them still proudly stands a battered flagstaff.

The Lal Baradari

The Lal Or Red Baradari is so called because of the colour with which its exterior is still ornamented. It stands on the opposite side of the road to the Great Chutter Munzil and was built by Sa’adat Ali Khan between 1789 and 1814. It is sometimes known as the Qasr-us-Sultan and was built as a throne room or a coronation hall for royal durbars.

Baradari literally means a building with twelve doors, and William Knighton describes this one as it was in the reign of Nasir-ud-Din Haider who ruled fourteen years after the death of Sa’adat Ali Khan. Like every room in the palace it had suffered alterations induced by Nasirud- Din’s obsession with the west. Rich scarlet and gold tapestry hung on the walls. A dim light filtered through the windows, enhancing the solemnity of royal receptions. A few full length portraits of the royal family hung upon the walls while the throne occupied the upper end of the hall.

It was of great value and consisted of a platform approached by six steps. Three sides were protected by a golden railing. The sides were of solid silver richly ornamented with jewels. Former kings had been content to sit in oriental fashion upon a velvet cushion placed on this platform ; but Nasir-ud-Din was too westernised and insisted upon having a gold and ivory chair.

A square canopy supported by wooden poles covered with beaten gold hung above a throne ornamented with precious stones. A magnificent emerald, said to be the largest in the world, hung at the front of the canopy which was of crimson velvet with rich golden embroidery and a fringe of pearls matching the window curtains. A gilt chair stood upon the right of the throne for the Resident.

At public durbars and state councils the nobility of Oudh and English officers were presented to the King. They advanced with a present which the King touched if disposed to be very gracious, or bowed distantly to signify resentment. The prime minister took the present and laid it on one side of the throne, and the presenter retired backwards to the right or left— usually to the right if a European, to the left if an Indian.

Then the King placed a necklace of honour around the neck of the Resident who returned the compliment. Then they advanced into the centre of the hall where necklaces were bestowed upon them. These necklaces were usually made of silver ribands and were worth from five to twenty-five rupees. At the conclusion of these cremonious levees the King conducted the Resident to the door of the apartment, poured attar of roses on his hands, and exclaimed, “God be with you!” before making his way to his private apartment.

It was in the Lal Baradari that the Queen Begum tried to install on the throne her adopted grandson, Moona Jan, when Nasir-ud-Din Haider died of poison in the Farhat Baksh, a stone’s throw away.

The building is now used as a museum and contains many things of interest including delicately executed portraits of men who in years gone by played a big part in the administration of the rich little kingdom of Oudh.

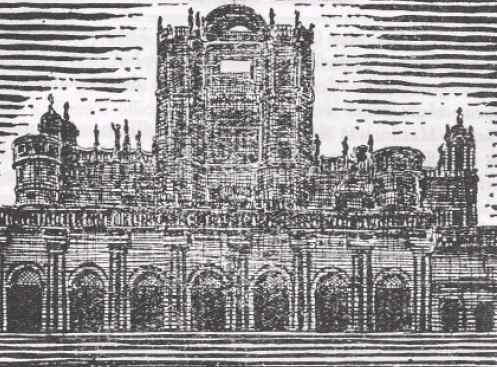

La Martiniere

“Here Lies Claude Mautin, Born at Lyons, the 5th day of January, 1735. Arrived in India as a common soldier and died at Lucknow, the 13th September, 1800, a Major-General, Pray for his soul.” General Martin directed in his long and interesting will that these words should be inscribed on the tombstone which covers his remains in La Martinière College, Lucknow. They were inspired not so much by a desire for self-advertisement but as an example to future generations of schoolboys of what determination and enterprise could do.

Claude Martin was the son of a French silk manufacturer of Lyons and first came to India in 1758 in the bodyguard of the Governor of Pondicherry. A year or two later he deserted, taking with him many of his countrymen whom he formed, with the consent of the English, into a band of French chasseurs with himself at their head. This continued until 1764 when in spite of his utmost efforts his men mutinied. A few years later found him making survey maps of Oudh. He was of an inventive turn of mind and attracted the notice of the reigning Nawab, Shuja-ud-Doulah, who obtained Martin’s discharge in order to entrust him with his own artillery park and arsenal.

La Martinière was originally called “Constantia” from General Martin’s motto, labore et constantia. The ceilings are domed and in the whole building there is not a single wooden beam. The original palace consisted only of the central portion and is of curious design., many of the rooms being linked half way up the walls by a circular purdah gallery so that in very truth the walls might have ears. The curved wings were built about 1840, in accordance with the General’s will which was written with scrupulous care in triplicate in both English and Urdu. The pillar standing in the lake was also built under the terms of his will as memorial. The lake originally covered a much smaller area and was enlarged in 1880 as a famine relief measure.

The artist Zoffany was an Oudh contemporary of Martin’s. In the very room through which she must so often have passed, hangs a picture by Zoffany of one of General Martin’s wives. She was of a princely family from which she ran way, to be discovered, by a French officer in the chikan work bazar in Lucknow. He bought her and sold her again to General Martin at the age of about eight. He educated her and finally married her. In this painting she is portrayed with one of Martin’s adopted sons.

The ceilings of all the rooms in La Martinière are in the bas-relief Italian style of raised plaster work in green, blue and pink. At intervals real wedgewood plaques are pegged into the walls, some only an inch or two in diameter and others about two feet by three, numbering some hundreds in each room.

Below the ground level in the tykhana General Martin lies buried. This is according to his directions, in order to prevent the building from being appropriated by Mussalmans. In pre- Mutiny days figures of French grenadiers, their arms reversed, guarded the tomb. The rebels broke these and even scattered General Martin’s bones to the four winds. When peace was restored they were collected and reinstated, but the statues were lost for all time. General Martin designed a most ingenious air cooling system. Great pillars run at intervals from top to bottom of the building. Down the centre of each is driven an air shaft with holes communicating with the various rooms through which it passes, thus enabling the hot air to rise and the cool air to take its place.

The school boasts a fine library which adjoins the chapel. Both must originally have been reception rooms. In the latter are some good stained glass windows and memorial slabs. One of these is to Captain Spence who for 64 years was connected with La Martinère. He came as a foundationer and ultimately became the estate superintendent. The estate covers an area of roughly two square miles. He left a substantial sum of money to the College when he died, which contributed largely to the Spence Hall.

An old-fashioned cannon named “The Lord Cornwallis” stands on the terrace. It was cast in 1786 by Martin who actually accompanied it to Seringapatam in 1792. In 1871 it was restored to the College by the Allahabad Arsenal. He also cast a large bell which he intended for use as a school bell. After the Mutiny it was found cracked and half buried in the garden. Some fifteen years ago it was restored and set in its place.

Huge stone lions adorn the upper terrace of the building; in their heads are spaces intended for lanterns whose beams would gleam out between the teeth of the monsters. At the corners are little turrets loop-holed every few inches. Still higher, statues adorn the terrace balustrades. Above the third storey a flagstaff stands on the crest of an enormous crown, which commands a glorious view of the city and the surrounding country.

During the insurrection the sixty-five boys of La Martinière withdrew to the Residency, where the Martinière Post was garrisoned by the teachers and bigger boys under the command of Mr. George Schilling, the Principal of the School. Mrs. Bartrum mentions in her diary the “little servants” who acted as messengers, and who were the younger boys of La Martinière. During the entire siege only three boys were wounded ; two died from disease.

On November 14 at 9 a.m., Sir Colin Campbell’s force started from the Alam Bagh on their relief march. Until they neared Dilkusha no resistance was offered them for they had come by an unsuspected route, but there they were met by musketry and artillery fire. This they soon overcame. Pushing on they rapidly drove the rebels out of La Martinière at the point of the bayonet and by noon were in position. Since those troublous times only the high floods of 1915 and 1923 have disturbed the even tenor of this famous school.

Lucknow Shrines

Two Shrines Lie To The south-west of the Chauk, a point of pilgrimage for many pious Muhammadans at Moharram time.

The more celebrated of the two was erected to Abbas, an uncle of Ali, who was cousin and son-in-law to the Prophet and who was killed in the battle of Kerbala. The word dargah means sacred threshold or door-place ; hazrat means saint. The shrine of saint Abbas was erected to house the metal crest which crowned the banner of Abbas, “conveyed thither long ago by a poor pilgrim from the west.” Hence the pilgrimage when the banners make obeisance on the fifth day of Moharram. During the Moharram banners are carried in procession to the shrine, where their bearers touch with them the sacred relic, before passing through the rear gateway.

About a hundred years ago the Dargah was a fine building some five miles from the King’s Palace. Upon a centre platform garnished with bunting and gay flags the sacred crest was fixed upon a pole. On the morning of the fifth day of Moharram crowds visited the shrine, each party bearing its own banner. Naturally enough no one was allowed to eclipse the cortege of the King in magnificence. An advance guard of half-a-dozen gorgeously caparisoned elephants carried the bearers of the banners accompanied by a military guard. Following them came a symbolical chief mourner carrying a black pole upon which hung a bow and two reversed swords.

Behind him came the King with his male relatives. Next was led a charger representative of the one Hosein was riding when he was killed. A grey Arab, on its reddened legs and sides arrows appeared to be buried to indicate the sufferings of horse and rider. A turban in the Arabian style and a bow and quiver of arrows were affixed to the saddle which rested upon a beautifully embroidered saddle-cloth. The trappings were all of solid gold. Attendants, gorgeously dressed, accompanied the horse with fly-whisks made of the yak’s tail. Sometimes fifty thousand banners passed through the shrine on this annual date, forming a continual stream from early dawn until dusk.

Occasionally the royal Begums accompanied by all the pomp and circumstance at their command made formal pilgrimage to the shrine. In the van marched the King’s bodyguard, resplendent in blue and silver and accompanied by band and colours. They were followed by two battalions of infantry in crimson and a company of spearmen in white, silver spear-heads flashing in the sun. More men in white carrying royal pennants preceded the litter of the Queen which was supported by twenty bearers changed every quarter of a mile.

They wore tightly-fitting garments under a loose scarlet coat lavishly adorned with gold embroidery and a scarlet turban, into which was pinned the goldfish badge of Oudh. The Queen had to be surrounded by women bearers when she embarked or alighted. They marched near the royal litter, followed by the gold and silver sticks, the chief eunuch upon an elephant, the ladies of the court in a heterogencous collection of vehicles, and finally an entourage of court soldiers, spearmen, story-tellers, hair-dressers, tailors, learned men versed in the Koran, and a hundred others.

Near the Dargah of Hazrat Abbas is the Talkatora Karbala, the rendezvous for the Moharram processions from the city for the final disposal of the tazias. It was built about 1800 by Mir Khuda Baksh Khan, a Naib of Sa’adat Ali Khan, and represents the tomb of Hosein.

Lucknow Bridges

Untilthe Twentieth century there were but two bridges spanning the Gumti at Lucknow, one iron and the other of stone. The latter was begun by the second Nawab, Safdar Jang or Mansur Ali Khan, whose first name is perhaps best known from his tomb at Delhi.

The erection of the bridge dragged slowly on. It was finally completed by the fourth Nawab, Asaf-ud-Doulah, Safdar Jang’s grandson. It stood near the existing Hardinge Bridge. Above the delicate tracery of the Mosque of Aurangzeb, abutted upon the more solid outlines of the Machhi Bhawan Fort, high stone walls commanding the coming and going of all who entered and left Lucknow by way of the river.

Early in the present century the bridge was condemned as unsafe and was demolished in 1911 to make way for the Hardinge Bridge which was opened on January 1, 1914, by Lord Hardinge, then Viceroy and Governor-General of India. At the same time he performed the inauguration ceremony of the King George’s Hospital. Upon the bridge a tablet states: “This bridge was constructed by the Public Works Department in place of the Nawabi Bridge, which was situated about fifty yards downstream and was built in 1780 by Asaf-ud-Doulah, Nawab-Wazir of Oudh.”

Lord Hastings visited Lucknow in 1814 and mentions that the stone bridge over the Gumti, although a handsome structure originally, was in a state of decay. He expressed surprise that the Nawab did not repair it but was told that the Nawab had a firm conviction that repairing the bridge would infallibly cause his death within the year.

Bridges seemed connected with superstition in the minds of the Nawabs, for Bishop Heber who visited Lucknow in 1824 mentions in his observations the broad and rapid stream of the Gumti, where there was a fine old bridge, but one which might in a few minutes be rendered impassable by any force without a regular siege. He goes on to say: “There are two bridges over the Gumty, one a very noble old Gothic edifice of stone of, I believe, eleven arches; the other a platform laid on boats, and merely connecting the King’s park with his palace.

Sa’adur Ali has brought over an iron bridge from England and a place was prepared for its erection , but on his death the present sovereign declined to prosecute the work on the ground that it was unlucky, so that in all probability it will lie where it is till the rust reduces it to powder.” This was the Iron Bridge which came from England in 1798 and, as has been said, lay in the cases in which it had arrived for over forty years.

The Iron Bridge was conceived by Rennie only twenty years after the first iron bridge had been made in England. It bears a resemblance to the one designed by him at Boston, Lincolnshire, over the River Witham. Rennie’s name once more came into prominence during the hard-fought controversy over Waterloo Bridge, also built to his design. Early in the nineteenth century a steam boat lay on the river, a vessel fitted up like a brig of war, bearing testimony to the King’s fondness for mechanical inventions. “He had a skilful English mechanic in his service, and himself knew more of the science and of the different branches of philosophy connected with it, than could be expected in one who understood no language save his own.”

General Martin who died in 1800 probably suggested that Sa’adat Ali Khan should purchase the iron bridge. In 1856 Polehampton refers to the English iron bridge as well as a handsome one on brick piers, plastered and coloured yellow. During Nasr-ud-Din Haider’s reign, he directed his engineer, a Mr. Sinclair, to erect the bridge ; he constructed piers for it in front of the Residency, but for some reason the project was once more discontinued. The bridge was finally placed in position between 1842 and 1847 under the direction of Colonel Fraser at a cost of Rs. 180,000 excluding the actual iron work.

Further downstream is the Bruce Bridge, known locally as Monkey Bridge, leading to the University buildings. The house immediately on the left, now occupied by the Vice- Chancellor of the University, was known as the Kabootar Wali Kothi, or Pigeon House, “a poultry yard of beautiful pigeons.”

About sixty yards to the east of this bridge blocks of masonry may still be seen on either bank. These formed the approaches to the Bridge of Boats, existent in 1857—over which the mutineers made their escape after the capture by Havelock of the Moti Mahal palaces. A little further down is the bridge in Sultan Ganj on Outram Road, which, with two railway bridges, makes a total of six all of which cross the river at Lucknow. There are also numerous ferries.

Between 1814 and 1827 King Ghazi-ud-Din Haider decided to build a canal to bring the waters of the Ganges across to the Gumti, thus irrigating parts of Hardoi, Unao and Lucknow. The work was put in the hands of some rascally contractors who carried it out so badly and unscientifically that the project failed, having cost a prodigious sum of money. Four bridges spanned the canal, all of which still exist, one by the Char Bagh, one north of the Sudder Bazaar and two close to Government House.

The old Stone Bridge which had seen so much proud pomp before the gradual decay of Nawabi days, still played a part in 1857, for the gallant Kavanagh who volunteered to make his way out of the Residency to guide Sir Colin Campbell’s relieving force into Lucknow, swam across the river and re-entered the city over the Stone Bridge, stealthily keeping under the shadow of the wall. Twice during his perilous journey was he challenged, but he managed to avert suspicion until he finally reached the British camp. “As he approached, an elderly gentleman with a stern face came out, whom Kavanagh asked for Sir. Colin Campbell. ‘I am Sir Colin Campbell,’ was the sharp reply. Who are you?” Kavanagh pulled off his turban and took out a short note of introduction from Sir James Outram.

Metro

Inaugurated in 2017

Lucknow's Metro dream turns into reality, Sep 5, 2017: The Times of India

September 5, 2017 marks the tipping point in Lucknow's history from being an old 'heritage city' to a 'city with the Metro'. Here's what the city's Metro has to offer commuters in the city.

Muhammad Ali Shah

1837—1842 When King Nasir-ud-Din Haider died by an unknown hand, drinking poisoned sharbat as he lay on his bed of silken cushions in the Farhat Bakhsh palace, the country had passed into such a state that anything might happen. Five years before, the British Government had instructed Colonel Low, the Resident, to uphold Nasir-ud-Doulah, one of the King’s uncles, as his successor. Directly the news of the King’s death was brought, Colonel Low hurried down the slope which led from the Residency to the palace.

Nasir-ud-Doulah was informed and escorted with all possible speed to the palace where he arrived at about three in the morning of July 8, only a few hours after Nasir-ud-Din had passed away. He was even then an old man and infirm, and this rude awakening in the middle of the night did not suit him ; so he retired unnoticed to a small room in the palace until morning.

Meanwhile the Resident took a firm grip of affairs at the palace, for he was expecting trouble. He placed his escort as sentries at every entrance of the palace, and a corps of Oudh Infantry took post at the main southern gate. Preparations were hurried forward so that the coronation of the new King should take place soon after daybreak.

There seemed nothing more for the Resident to do. He repaired to the verandah overhanging the Gumti, and there he sat, enjoying the cool dawn breezes and discussing plans with his assistants.

Suddenly news was brought to him that the Queen Begum, step-mother of the late King, was advancing upon the palace with a large armed band, intending to force the officials to crown a child called Moona Jan, either her illegitimate son or her adopted grandson, as King of Oudh.

Captain Paton, one of Colonel Low’s assistants, at once rushed to the south gate, collecting four men as he ran, to find a seething mob already surging round the gate. The palace guards and the police had done nothing to disperse the mob who had already forced a passage. In poured the rabble, sweeping aside all resistance, even beating Captain Paton to the ground with lathis and musket butts. They spared his body servant who escaped out of the gate in time to bring an advance party of thirty sepoys to save his already insensible master’s life from being beaten out of his body.

The rabble was by this time completely beyond control. Colonel Low was helpless and under the guard of a rebel sentry. He was forcibly taken to the Lal Baradari where the child Moona Jan was already seated, upon the throne, listening to the state band playing, incongruously enough, a discordant version of ‘God Save ihe King’! The Resident and his assistants were dragged through the unruly crowd to the throne, where Colonel Low was peremptorily ordered to congratulate the young pretender. The penalty of refusal was, he was assured to the accompaniment of much brandishing of swords and daggers, instant death.

He refused, however, to show the least agitation. Quite calmly he represented to the Begum that even if she did kill him, the British Government would exact a large fine from her. She refused to listen, but her Vakil had sense enough to realise the truth of this assertion and to see that he and his mistress would suffer a heavy penalty if any British official were harmed. He took matters into his own hands. Grasping Colonel Low by the arm, he thrust a way through the muttering mob, shouting to all and sundry that by order of the Begum the Resident was to be escorted from the throne room.

Even so, it was not an easy path. By dint of much pushing and elbowing they eventually reached the exit, accompanied by Captain Shakespeare, the second assistant. There in the garden they found five infantry companies and four guns which had just arrived from Mariaon under the command of Colonel Monteith. Colonel Low forthwith took command. He ordered the Begum and her youthful candidate to surrender, giving the old lady fifteen short minutes in which to disperse her followers. She still hoped against hope to triumph and would not obey. Colonel Low relinquished command of affairs to the soldiers.

Then and there the guns opened fire upon the throne room while Major Marshall led a party of the 35th (Company’s) Infantry to the attack, first firing upon the now panic-stricken people, then resorting to the bayonet. The swashbuckling insurgents turned into cowering refugees, fleeing in wild disorder and leaving fifty of their number dead or wounded in the building. The British casualties were three or four wounded only.

The story goes that as the sepoys charged into the throne room they saw a number of wildlooking men advancing threateningly upon them from the opposite end of the hall. Not until they opened fire did they realise that they had mistaken for the enemy their own images reflected in a large mirror.

While these people of Oudh shed their blood in a futile cause, the dead body of their late king lay in state in one part of the palace, while the new king as yet uncrowned, sat, according to some authorities, cowering in fear of his life in an upper chamber of the palace, or according to others, sleeping peacefully throughout the proceedings. Ultimately the Begum and her protégé were captured and sent to Chunar as state prisoners.

Nasir-ud-Doulah was finally crowned, upon which he changed his name to Muhammad Ali Shah. He proved worthy of the Government’s choice, for he ruled as well and as wisely as his health would permit. To some extent he refilled the state coffers, sadly depleted almost to the last few rupees by the wanton extravagance of his predecessor. The throne itself, so insecure for those who sat there, was of gold, embroidered in pearls and small rubies.

Some contemporary authorities held that he ought not to have succeeded to the throne, for Sa’adat Ali Khan had sons; and although his eldest son Shams-ud-Din died during his father’s life-time, his four sons were not out of the line of succession. Their claims to the throne of Oudh were urged by Captain White in a pamphlet entitled ‘The Prince of Oudh’. However that may be, Muhammad Ali Shah was the one ruler since his brother’s death who tried to stem the tide of degeneracy which ultimately lost the line their kingdom.

Enfeebled and old though he was, he decided to beautify the Husainabad area of Lucknow. To that end he began building a structure known as the Sat Khanda. which derived its name from the fact that it was designed to have seven storeys, from the topmost of which the King could lie on his couch and watch the progress of his building schemes. No more than five storeys were finished before he died. They stand incomplete to this day, gradually crumbling to decay in a corner of the Husainabad Park in which he built the Husainabad Tank, a graceful pool bordered at one end by another of his conceptions, the Taluqdars’ Hall; also the florid, tawdry-looking Husainabad Imambara where he lies buried.

The Honourable Emily Eden, on a tour with her brother Lord Auckland, visited Lucknow in 1837. The King sent relays of coach horses to facilitate her approach to Lucknow and caused tents to be pitched for her comfort at convenient intervals along the route. The King’s own cook also sallied forth to meet the party.

The Governor-General himself remained at Cawnpore, for etiquette did not permit the King, who was by this time bed-ridden, to receive a distinguished guest from his couch and without the pomp and ceremony which were a fitting accompaniment to the meeting of an Indian King with the British King’s representative.

In 1837 a new treaty was drawn up by which Colonel Low hoped to guard against a repetition of such misrule as the former one, but it was never ratified as the Court of Directors for some reason did not approve of it.

Muhammad Ali Shah did his best to rule well, but it was a feeble and incapable best, for the poor old man was too broken in health to accomplish much. Hakim Mahdi was reinstated as minister but he died soon after he had resumed office. His successors, worthy men enough, lacked initiative to inaugurate a new system of government.

The King was popular and had a certain amount of influence over his subjects, especially as he made determined efforts to improve the city and did not dispense all thought and substance upon his own palace. He spent large sums in making Husainabad a broad and handsome street. When he died his treasury contained about £800,000. This was substantial enough, taking into consideration his extensive building operations and the fact that he had succeeded to a bare pittance.

Prince Alexis Soltikoff visited Lucknow at the close of 1841 and describes Husainabad as a large and noisy street, terminated by a gateway of Moorish design, behind which towered slender minarets with small golden domes gleaming in the sun. At one end of the broad highway stood the Imambara, enclosing aviaries of rare and lovely birds, several edifices of Eastern design, and a small gilded mosque erected over the remains of the queen mother. Only a few months later, in May 1842, the King himself was laid to rest in a silver sarcophagus, to be succeeded by his second son.

The Maqbara Of Amjad Ali Shah

King Amjad Ali Shah came to the throne of Oudh in 1842. He reigned until he died on February 13, 1847 “of an ulcer, or some such sore on his shoulder, and… the sore must have been poisoned by some one, most probably by one of the physicians bribed by some one who benefited most by his death…When the King, Amjad Ali Shah, fell his end approaching, he ordered the council-chamber to be prepared and fresh carpets to be spread, and new cushions, and he had his beard trimmed, and put on new and splendid clothing and, having lain down in the council-chamber, he sent for the queen.

There they both wept, and he spoke much to her in whispers. The boil or ulcer on his shoulder at that time was as large as a saucer, and the flesh all eaten away, it was said, from some poisonous ointment given by the physician. How can I tell if the report was true? Such was the rumour in the palace, and of course the physician would not have dared to do so of himself.

He must have been bribed to do it. “After much whispering talk he said he would sleep, and the queen laid down his head gently and covered it. The attendants, suspecting he was dead, got her away with great difficulty and she thought he was still sleeping; but he was dead. He died, like a king, in his royal robes on his throne, in his council-chamber.”

When the King was dead, the sound of wailing was drowned in the shouts of gladness proclaiming the new King Wajid Ali Shah. The Queen mother was forced to abandon her dead, to clothe herself in gorgeous raiment and attend the coronation of her son. The body was left to the care of servants who prepared it for burial within the dark and silent palace. From without came the noise of joy and commotion, cannons firing and bands playing. Amjad Ali Shah died early in the morning. The coronation ceremony, when the court lords took the oath of allegiance, lasted until past midnight. When the poor widowed queen was at last permitted to return to the palace, she found her lord and master already buried. He lies in the Imambara which faces Hazrat Ganj, near Mission Road and the Lal Bagh, shielded from view by a large gateway.

The building has little architectural beauty. It is a single rectangular chamber approached by a fine flight of steps. At the top of them a stone tank abuts on to a stone terrace for ablutions of the faithful.

Shabby doors fitted with broken panes of glass afford a glimpse of the interior now furnished with little but cobwebs. Once this was lavishly lined with silken carpets, wonderful chandeliers and priceless art treasures, but during the troubles of 1857 the local hooligans could not withstand the attractions of loot. They stripped the Imambara of everything of value. Beneath a trapdoor in the centre of the floor a few steps lead to the vault where the King’s body lies, forgotten and forsaken.

On March 12 and 13, 1858, after the Begum Kothi had been taken, the British troops pushed on to Amjad Ali Shah’s tomb from which they drove their enemies with the help of a couple of batteries of guns, which made two breaches in the south-eastern wall of the Imambara enclosure. Two companies of the 10th Foot and about a hundred men of the Ferozpore Sikhs formed a storming party. Feeble resistance was offered and the troops pressed on to an outlying building of the Kaiser Bagh Palaces.

When Oudh became quiet this Imambara was used as the English Church until 1860 when Christ Church was completed. Lord Canning during his second visit to Lucknow attended divine service in the building.

Christ Church was built as a memorial to those who lost their lives as a result of the Mutiny. Its walls bear many brass tablets recalling names and places associated with unparalleled bravery. The Reverend Henry Polehampton, with his infant son, is here remembered: he was severely wounded whilst shaving and later succumbed to an attack of cholera. Nawab Mohin-ud-Doulah Bahadur of Lucknow erected a tablet to Captain Maclean of the 7th Regiment, Native Infantry, as a token of his friendship and regard. The great Kavanagh who took his life in his own hands “with the devotion of an ancient Roman”, and Major Johnson, who had been through the Crimean and Persian campaigns—these and many others are remembered in the quiet and peaceful Church.

In the earthquake of 1933, the Cross on the spire of the Church was twisted until it faced down Hazrat Gunj.

The Maqbara Of Sa’adat Ali Khan

Contrary To Custom, Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan did not build his own tomb ; for the place where it stands with that of his wife Khurshaed Zadi, overlooking the present Oudh Gymkhana Club tennis courts, was formerly the site of a royal palace.

Before Sa’adat Ali Khan came to the throne in 1798 he lived for some years in Calcutta and adopted many European customs and ideas, among them a belief in the merits of the East India Company.

Asaf-ud-Doulah died in 1797 leaving no legitimate heir. A claimant who pretended to be his son was actually allowed to sit on the throne for four months until the British deposed him in favour of Sa’adat Ali Khan, half brother to Asaf-ud-Doulah. The latter did much to beautify his capital with palaces, mosques and bridges, to the detriment of the state coffers which suffered still more from the lavish splendour in which the Nawab lived. On the accession of Sa’adat Ali Khan life in the capital proceeded as usual, and the Nawab continued to indulge his extravagant tastes, paying no attention to the duties incumbent upon him. Lord Wellesley was then Governor-General and he decided that the Nawab’s army must be disbanded. Financial difficulties became more and more acute and in November 1801, by the Treaty of Lucknow, the Nawab relinquished all claim to ten districts receiving in return British assistance for internal and external defence.

At the same time he made a vow at the shrine of Hazrat Abbas to devote himself thereafter wholly to the welfare of his state. Colonel Sleeman, Resident at Lucknow from 1849-56, says that he kept his vow, and no King of Oudh ever conducted the Government with so much ability as he did for the remaining fourteen years of his life. As late as 1880, “he was still remembered, even by the large landholders—to keep whom in check was one of his chief aims—as the best, wisest and strongest administrator the province ever knew.” He gained an unmerited reputation for parsimony and extortionate dealings, probably because he employed Europeans to cope with refractory zamindars and did not allow the enormous and useless expenditure usual in an eastern state.

He had nine sons. For his favourite wife, Khurshaed Zadi, he built the Khurshaed Munzil, now the Martinière Girls’ School, as well as many other fine buildings including Dilkusha Palace and the Moti Mahal. In spite of this he cleared his kingdom of debt. At his death fourteen crores of rupees constituted a reserve treasury.

On July 11, 1814 Sa’adat Ali Khan died and was succeeded by his son Ghazi-ud-Din Haider. The latter announced that as he had taken his father’s place, his father must have his. In accordance with this somewhat astonishing reasoning, he pulled down his palace and built instead his father’s tomb on the site. It is a fine conception although its proportions have since been spoilt by a grass mound piled around its foot. From the base of the dome the panorama of Lucknow unfolds itself to the bold adventurer who decides to risk the cracks produced by a recent earthquake.

The floor is paved with squares of black and white marble. A marked depression running from north to south indicates the King’s last resting place. The tomb proper flanked by those of his two brothers, lies in a vault beneath und is reached by a dark and narrow winding stair. In the same building lie three of his wives and three daughters. His favourite wife, Khurshaed Zadi, mother of Ghazi-ud-Din Haider, is buried a stone’s throw away in a similar mausoleum slightly smaller than his own.

During the Mutiny both tombs were strongly fortified with concealed cannon which effected considerable damage to Havelock’s force during the first relief. On March 13, 1858 Frank’s column occupied the courtyard of the tombs and, from the scant shelter it afforded, stormed the Kaiser Bagh.

In their hurried flight from Lucknow early in 1858, the rebels abandoned near the Jama Masjid a number of tin boxes and leather cases containing gunpowder. General Outram ordered the sappers to destroy them and so, on March 17, under the direction of Captain Clerke, Adjutant of the Royal Engineers, they conveyed them to a large and deep well and began to throw them down. One of the boxes scraped the side of the well and blew up, igniting box after box, until the whole exploded, killing Captain Clerke, Lieutenant Brownlow of the Bengal Engineers, a corporal, a lance-corporal and twelve sappers of the 23rd Company of Royal Engineers.

A flat marble slab surrounded by a low iron railing marks the spot of this disaster a few yards from the resting places of Sa’adat Ali Khan and his wife. So a Muhammadan eastern potentate lies cheek by jowl with such sturdy British yeomen as Sapper Andrew Fairservice, Sapper James Bunting and Sapper John Yeo.

The Mariaon Cantonment In The Eighteen Fifties

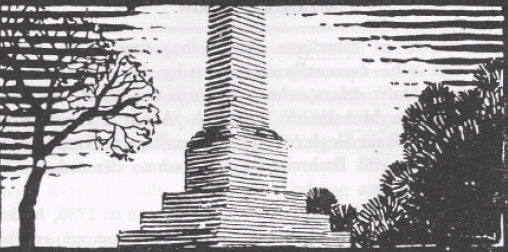

Between The third and fourth milestone on the road leading from Lucknow to Sitapur, about a hundred yards from the left hand side, there stands an obelisk—all that remains of what was once a large and flourishing cantonment.

Many years before the cantonment existed, an ascetic named Mandal Rikh lived in a great forest. The place where he dwelt became known as Mandiaon. For a long time it was peopled by the Bhar tribe eventually driven out by one of Saiyid Salar’s Lieutenants, Malik Adam, who in his turn was killed and buried in the Subhatia Mohalla of Lucknow. About a hundred and fifty years later Raja Singh conquered the village and made it over to his Kayasth and Brahmin followers whose descendants live there to this day.

When Sa’adat Ali Khan came to the throne in 1798, he built a cantonment called Mariaon for the European community which flourished during the 19th century. There were lines for three native infantry regiments, a battery of European horse artillery and a bullock battery of regular native artillery. At Mudkipur, a couple of miles away, were the 7th Light Cavalry. A little way down the Lucknow-Sitapur road stands a large house with semi-circular gates—the few remaining traces of a rich Nawab’s house. On either side of each gate stood a cage, one containing a fine tiger, the other three or four small leopards. Begging at the gate near by sat an old Mussalman Fakir, naked except for a cloth round his loins.

A little further along the road, on the left-hand side, is the shed of another big house, still called “Beechy Sahib ka Bangala” by the villagers. Here it was that the Reverend Henry Polehamton lived with his wife. Mr. Polehampton, in one of his long and interesting letters, says : “I think I told you long ago, they say this house is haunted… and that no one but a Padre can live in it. They say Mr. Beechy who died there haunts it.” In those days it had the best garden in cantonments, with plenty of strawberries, oranges and lemons and quantities of other fruit trees, vegetables, and flowers.

Life in cantonments then was very much as it is now, only cheaper. The “Khansama” or house-steward was paid ten rupees a month ; a “khitmutgar” or table-attendant seven ; the dhobi, ayah, cook and bearer, eight each ; bhisti, sweeper, chowkidar and palanquin bearers four each ; punkah coolies, gardeners, and grass cutters three ; and the goat boy one. The average rent was about sixty pounds. Board and lodging and servants came to about £280 per annum.

The Polehamptons kept six or seven goats and every evening and morning, before tea and breakfast, they were milked just outside the verandah and the milk carne in foaming. Most of the servants were married. Altogether there were fifty children in the compound. The servants’ houses were built of earth and were low and dark.

There was an ice club and a book club. The subscription to the latter was heavy, but then everything English was expensive and books were badly needed. They had wood fires for there was no such thing as coal, wood costing in the bazaar a rupee for three maunds. They had to depend a good deal upon local products for food, such as custard apples and Indian corn grown in the garden which they roasted for dessert ; and green young lemons.

The church was near the Polehamptons’ house and held about a hundred people. A little distance away along a broad metalled road was the cemetery shaded by fine trees. The route, now inches deep in sand, may still be seen leading off the main road to the right and passing through a village on the site of the old Bullock Battery lines.

A little beyond the village lies the graveyard, a sorry sight of dilapidated tombs. Trees have thrust their limbs between the masonry. Head stones lurch drunkenly at a precarious angle. Only two lead inscriptions have escaped the pillagers’ hands, those of Lieutenants MacDonnell and Richards. The former was the Adjutant of the 2nd Punjab Cavalry, and was killed in action at Courci in March 1858.

The enemy were in retreat, but they showed indomitable courage when the British troopers charged through them three times. They never even wavered. During these charges MacDonnell was killed and Captain Gosserat of the 34th Madras Light Infantry, then in command of a squadron of the 1st Punjab Cavalry, was wounded. He lingered on for over a fortnight, being laid to rest in the Residency Cemetery. Lieutenant Richards took part in the attack on Birwa Fort in Hardoi, carried out by Brigadier Barker as late as October 1858. He was wounded there and brought back to die early in December at Mariaon.

Although disease and epidemic carried away a large percentage of the population, life was not all funerals and Mariaon boasted a fine park. Dinner at three was “tiffin” to fashionable Anglo-Indians who dined at eight. A band of one of the regiments played every evening at sunset for about an hour. Gentlemen would get out of their buggies and go about talking to ladies at their carriage doors. At about seven they all went home.

All that remains of the Mariaon Residency are the foundations upon which has been erected an obelisk. Affixed to it is a plaque which reads:— “This pillar commemorates old Mariaon cantonment garrisoned in 1857 by the 13th, 48th and 71st Native Infantry. A large proportion of the regiments mutinied on the evening of May 30, 1857. This pillar marks the site of the Residency Bungalow occupied by Sir Henry Lawrence, K.C.B., on that memorable occasion and subsequently by rebels. The mutiny of May 30 was crushed by a small force of British and loyal Indian troops, and the rebels were routed, but the Mariaon cantonment was abandoned on the 29th June, 1857, when Sir Henry Lawrence’s force concentrated on the Lucknow Residency and the Machi Bhawan.” Sir Henry refers to the Mariaon Residency in one of his letters as being nearly as large as his town house in Lucknow.

On May 18, 1857, Sir Henry wrote: “Time is everything just now—time, firmness, promptness, conciliation, and prudence.... ten men may in an hour quell a row which after a day’s delay may take weeks to put down.”

False alarms of risings were rife. Sir Henry took no notice of a rumour that a rising was timed to begin at 9 p.m. on May 30. That evening some officers on his staff were dining with him at the Mariaon Residency. After dinner they strolled out on to the verandah. When the 9 o’clock gun fired, Sir Henry said smilingly, “Your friends are not punctual.” Scarcely had he said it when there was a burst of musketry and fires were seen burning in all directions. Hastily the horses were saddled and Sir Henry and his staff rode off to the camp of the 32nd Regiment where the men were already drawn up for action together with the European battery.

Almost immediately the sepoys of the 71st Native Infantry appeared and began firing upon the 32nd, but they fled when the English troops retaliated. In their flight they murdered Lieutenant Grant commanding a picket in cantonments.

In spite of patrols the mutineers pillaged and looted all night, Brigadier Handscomb being killed by a chance bullet. Only the Residency escaped the attention of the insurgents. Next morning it was estimated that about seven hundred men had remained faithful from the three native infantry regiments and the 7th Light Cavalry.

At Mudkipur the men had burnt and sacked the Cavalry lines. Cornet Raleigh, a boy of seventeen, had been sick in quarters in Mudkipur: when attemping to mount his horse that morning, he was killed without a chance to defend himself. The troops remained in Mariaon while Sir Henry transferred his headquarters to the Lucknow Residency. When everything was ready the entire European population withdrew behind the walls of the Machhi Bhawan and the Residency. The famous siege had begun!

The Machhi Bhawan

Although All Trace Has long since vanished of any part of the actual Machhi Bhawan fort, the name lingers and applies to the mound upon which the Medical Colleges now stand.

In 1470 A.D. a Muhammadan saint named Sheikh Mina was born at Lucknow. He was educated by an eminent dervish, Quiran-ud-Din. At his death a tomb was erected over his remains. It is carefully preserved to this day and is the oldest identified monument in Lucknow. It is a place of pilgrimage.

The city in those days was known as Lukshmanpur. When Mahmud of Ghazni invaded India he brought with him Sheikhs and Pathans some of whom settled in Lukshmanpur. A Hindu architect name Likhna designed a fort for them known as Likhna Kila which gradually shortened into Lucknow. Within its sheltering walls stood the Panch Mahal, so called because it was five storeys high.

When Sa’adat Khan first moved his court from Fyzabad to Lucknow in 1732 he hired the Panch Mahal and another building known as the Mubarak Mahal for about five hundred and fifty rupees a month. Then Nawab Safdar Jang came to the throne in 1739. He strengthened the fortifications of the old fort and renamed it Machhi Bhawan, or Fish House, “machhi” meaning fish and “bhawan” being the Sanskrit word for house. He enlarged it to reach the river. High walls encompassed it. From the water it looked like a fortress commanding the old stone bridge now swept away. On the south-east side it overlooked the Residency. Beneath the outer walls ran the most frequented thoroughfares of the city.

Asaf-ud-Doulah, the fourth Nawab, who succeeded to the throne in 1775 and is generally acknowledged to have been the greatest of the rulers of Oudh, strengthened the fort still more with round earthen bastions. Within he built a palace facing the Gumti, consisting of six main quadrangles surrounded by pavilions. Entrance was by two noble gateways, the outer one containing the Naubat Khana. where musicians played at stated times every day. The state apartments encompassed the main courtyard in the centre of which was a well. Fountains played and streams wound in and out to keep it cool during the summer.

In 1784 the Great Imambara was built as a famine relief measure within the Machhi Bhawan area—which gives some slight idea of the size of the fortress.

In 1857 the buildings within the fort were the property of Nawab Yahuja Ali Khan who sold them to Sir Henry Lawrence for Rs. 50,000. Murmurs of unrest were even then beginning to be heard, so Sir Henry gave orders that the fortifications of the Machhi Bhawan should be strengthened. By the middle of May he was prepared for all eventualities and had distributed his troops.

To the Machhi Bhawan he sent a hundred Europeans, three hundred sepoys and about twenty guns, with a large quantity of ammunition. On the last day of May he hastily transferred his headquarters to the Lucknow Residency from Mariaon and feverishly fortified the surrounding positions. Cellars were excavated and ammunition from the Machhi Bhawan stored in them. Preparations went on more or less unimpeded until news was brought that the advance guard of a force from Nawabgunj had already reached Chinhut and was preparing to advance on Lucknow.

At sunset on June 29, British troops quietly withdrew with their entourage into the Residency and the Machhi Bhawan; on the 30th a force of six hundred and eighty-six men and eleven guns advanced to the disastrous battle of Chinhut. The little force was badly defeated. It was forced to retire but held its own until the guns from the Machhi Bhawan checked the oncoming enemy, enabling it to withdraw into the Residency.

The guns from the fort prevented the enemy from crossing by the stone bridge, but early in June the river dwindled until it was fordable and they made their way across into houses overlooking the Residency from which they proceeded to pour musketry fire into the British position.

Thus the siege began. At daybreak on July 1 the besiegers made their first attack on the Residency. It was repulsed, but Sir Henry came to the conclusion that there were not enough troops to defend both positions, so a semaphore was sent from the Residency to the Machhi Bhawan saying, “Spike the guns well, blow up the fort, and retire at midnight.” At that hour, then, the defenders of the fort, commanded by Colonel Palmer, marched into the Residency with guns and treasure, leaving two hundred and forty barrels of gunpowder, which blew up with a terrible explosion a few minutes later, a train of gunpowder having been laid by Captain M. C. Thomas of the Madras Artillery.

Mrs. Bartrum records in her diary: “Last night the Machhi Bhawan fort was blown up. It was such a tremendous shock that we all sprung out of our beds.... thinking that the sepoys had really blown up our defences and forced their way in. Our room was so thick in dust that when we had lighted a candle we could scarce see one another.

The next morning a voice outside the Water Gate of the Residency was heard shouting, “Arrah, then, open your gates.” The speaker was a private of the 32nd Regiment, who had been drunk the night before and asleep when the evacuation took place. He had been blown up—which rapidly sobered him—but he was unhurt.

The force of the explosion had torn every stitch of clothing off him and he arrived at the Residency stark naked. Nothing more is heard of the fort until early the following year, when on March 16 Outram’s force captured it after slight resistance. The same year it was rebuilt and after being strongly fortified was occupied by troops and officers’ families.

In 1905 when King George V visited India as Prince of Wales, he came to Lucknow in December and laid the foundation-stone of the Medical College. In January 1912, Sir John Prescott performed the opening ceremony of the buildings now known as King George’s and Queen Mary’s Medical Colleges.

The Moti Mahal

The Moti Mahal, Or Pearl Palace, was thus called because its original dome resembled a pearl. It has been through many vicissitudes since then and was re-roofed in 1923. The name now embraces two other erstwhile famous buildings, the Mubarak Manzil and the Shah Manzil. The Moti Mahal was built by Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan between 1798 and 1814. The other two were added by his son and successor Ghazi-ud-Din Haider. They are now the property of the Maharaja of Balrampur.

The royal fish badge ornaments the entrance gateway, from which a wide drive leads between gay flower beds to the Moti Mahal itself. Here at the Mubarak Munzil fights of large animals took place, generally in a special enclosure where stood a balcony for the King and his attendants.

In 1856 an excellent road with lamp posts on either side led to the Shah Munzil, a spacious palace stretching to the Gumti. It had a lovely garden where lemon and orange trees mingled with rose and pomegranate. Fountains and statues adorned the garden where gold and silver fish gavotted.

On September 25, 1857, the relief column under Havelock took a route unforeseen by the enemy. After sharp skirmishing around the area of the Yellow House, they proceeded unmolested until they reached the Moti Mahal where there was some heavy fighting. Guns from the Kaiser Bagh and the Khurshaed Munzil took toll of them until they reached the lee of the Chutter Munzil.

They ejected the garrison of the Moti Mahal and left the wounded there together with the heavy guns and ammunition under the command of Colonel Robert P. Campbell of the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry. Their protection proved insufficient and the whole of the next day had to be spent in extricating them. Colonel Campbell got out the next night but was shot in the knee, his leg being later amputated. He could not withstand the shock and died, and is commemorated with the other officers and men of the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry in the Residency Cemetery.

On that day, September 26, Brigadier Cooper of the Artillery and Dr. Bartrum were both killed in the courtyard of the Moti Mahal. At the outbreak of the Mutiny Dr. Bartrum with his wife and child was at Ghonda, about 80 miles from Lucknow. By June 6, Mrs. Bartrum says that they were becoming alarmed. The next day Sir Henry Lawrence sent a messenger via Secrora, ordering the ladies and children into Lucknow for better security, Mrs. Bartrum and her baby were confined within the Residency during the siege and on September 23 she wrote, “Such joyful news! A letter is come from Sir James Outram in which he says we shall be relieved in a few days ; every one is wild with excitement and joy. Can it really be true ?”

Three days later, the very day her husband was killed, she was up with daylight and dressed her baby in the one clean dress which she had kept for him throughout the siege until his father should come. The next day, she was still watching for her husband and still he came not. On the 28th the servants brought in a few things belonging to him. His sword, his pistol, and his instrument case had all been taken. The grief-stricken widow recognised her dead husband’s horse.

During the second relief, when the rebels had been driven out of the Khurshaed Munzil, they were pursued to the Moti Mahal with desperate bayonet fighting, when the British force gradually drove their opponents from room to room and finally stood panting in sole possession. A garden path still clings to the original garden wall and leads to a stone erected in 1932 stating, “This tablet commemorates the reuniting of the two wings of the 90th Perthshire Light Infantry, now the 2nd Battalion, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), near this spot during the relief of the Residency, 17th November, 1857.”

Another, visible from Clyde Road, says that “About 20 paces from this spot in the side wall of the Moti Mahal was the gap through which Sir James Outram and Sir Henry Havelock passed on their way to meet Sir Colin Campbell when the relieved and relieving forces joined hands on the 17th November, 1857.” This historic reunion in the garden of the Khurshaed Munzil has been commemorated in a famous picture, “The Meeting of the Generals.”

The Musa Bagh

Further Afield Than Most Of Lucknow’s historic spots lies the Musa Bagh. The effort of finding it is well rewarded by the calm and peaceful atmosphere of the old house, as it reigns supreme over the green and fertile fields stretching on every side. From the Great Imambara, go through the Rumi Darwaza past the Husainabad Imambara and straight on. The local inhabitants are, for once, well informed of its whereabouts. After one or two vicissitudes, and remembering to go in the direction of the water works, you come suddenly upon a wide straight road, wider than the Hazratganj, once shaded by lofty trees.

Upon a commanding site stand the remains of a wall weatherbeaten into that beautiful colour which only old brick-work can attain. The site was originally chosen and laid out as a garden by Asaf-ud-Doulah who transferred the seat of government from Fyzabad to Lucknow in 1775. His half-brother Sa’adat Ali Khan succeeded him and built a house at one corner of the Musa Bagh.

Designed by General Claud Martin on the lines of an English country manor, it was badly knocked about in 1858, but it is possible to reconstruct it in some measure in the mind’s eye. In the centre, a large hall stood supported by two noble columns of pillars from which other rooms gave off. At each corner was a small circular chamber containing a winding stair. In the centre chamber, curiously enough, a small well penetrates deep into the ground. Little of interior decoration remains except some weather-beaten stucco work touched here and there with faded colouring. A Mr. Sherer alludes to the “effigies of Nasur-ud-Din Haider” which adorned the walls of the Musa Bagh.

Oval holes cut in the high wall encircling the garden look over the fields sloping gently to the Gumti, and from this vantage point the Nawab-Wazir would watch wild beast fights whose fame had spread over all Oudh.

The contests between the smaller animals such as antelopes took place at the Musa Bagh. These animals were caught in the lower hills of the Himalayas and trained to fight. The two deer would trot towards each other, manoeuvring for position, crossing their antlers, retreating and advancing until their antlers became interlocked and each antelope strained his whole frame to press his adversary backwards.

At last one animal would show signs of strain and inch by inch the stronger opponent would gain ground. On pushed the stronger antelope, head depressed, every muscle starting, every limb dancing with animation, whilst his opponent rolled his eyes wildly, becoming paralysed with terror. His graceful limbs twitched with fear as he yielded ground.

Finally they reached the limit of the enclosure; still the remorseless enemy would push with renewed vigour. Resistance finally broke and the oppressed antelope turned sideways as if to escape by flight. In a moment the sharp points of the victor’s antlers plunged into the flanks of the vanquished. The animal thus gored groaned with pain as he sank down, big tears coursing down his cheeks. Again and again he would try to escape, but there was no hope. Finally the stronger antelope, watching his opportunity would rush at his adversary and plunge his blood-tipped horns into the flanks of his exhausted stag which fell never to rise again.

Strangely enough the great insurrection of 1857-58 both began and ended at the Musa Bagh. The 7th Oudh Irregular Cavalry were stationed there. Having been told that a type of newly issued cartridge had been greased with cow’s fat, they refused to bite it. Sir Henry Lawrence issued an order that they were to be deprived of their arms, and then events began to move.

The scene of action left the Musa Bagh until March 1858, when the Queen Mother and her son took up their headquarters there with a. force of some nine thousand men commanded by prominent leaders. Sir Colin Campbell naturally decided that they must not be allowed to remain there and on March 19 at 6-30 in the morning, Outrarn moved off towards the Musa Bagh. His force consisted of two squadrons of the 9th Lancers, Middleton’s Field Battery, three companies of the 20th, seven companies of the 23rd, the 79th Highlanders, and the 2nd Punjab Infantry, supported by Hope Grant’s guns and musketry fire from the opposite side of the river.

At the same time Brigadier Campbell advanced from the Alam Bagh and cut off the retreat of the flying rebels. But he was late and although his force pursued the rebels for some distance a great number of them slipped through to Fyzabad.

Captain Wale raised and commanded the 1st Sikh Irregular Cavalry and he and his regiment were among the pursuing force. After several miles, however, he gave the order to halt. “Then from the far side of a ravine, a solitary figure fired his musket at a group of officers,” killing Captain Wale. He was the eighth son of General Wale, out of a family of sixteen, and lies buried in the Musa Bagh, under a stone erected by Captain L. B. Jones, Acting-Commandant, 1st Sikh Irregular Cavalry, “as a token of regard for his officer, whom he admired both as a friend and a soldier. Captain Wale lived and died a Christian soldier.”

Captain W. Heley Hutchinson and Sergeant Newman, both of the 9th Royal Lancers, were badly wounded while pursuing the enemy from Musa Bagh and both lie buried in the Wilayati Bagh. When the rebels had finally been driven from the Musa Bagh by sharp fighting, a small force was detailed to occupy it, and at Lotan Bagh nearby lies Major John Griffith Price, 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen’s Bays), who died of fever at the Musa Bagh, on the 12th of May, 1858. This force was soon withdrawn, and but for an occasional intrusion the Musa Bagh is given over to peaceful tillers of the soil.

Nasir-Ud-Din Haider

1827—1837

Following Tradition, the second King of Oudh, who succeeded to the throne in 1827, changed his name from Suleman Jah to Nasir-ud-din Haider.

King Ghazi-ud-Din Haider died—and it is significant of the violent deeds prevalent in those days that historians add that he died “a natural death”—on October 20, 1827, to be succeeded by one whom he had declared to be his son by a slave girl, but who was popularly reputed to be the son of a washerman attached to the palace.

This rumour is supported by a document which states that “Ghazee-ood-Deen had no son and only one daughter, who married her cousin and had issue Mossem-ood-Doulah, the true heir to the throne. Ghazeeood- Deen, instead of leaving the throne to his true heir and grandson Mossem-ood-Doulah, left it to Nuseer-ood-Deen Hydeer.” Moreover, Colonel Low, the British Resident in Lucknow, wrote a memorandum saying that a letter was intercepted from the Padshah Begum addressed to the late Mr. Secretary Stirling to the effect that Nasir-ud-Din Haider was not the rightful heir, nor even the son of Ghazi-ud-Din Haider.

Although Nasir appeared to inherit none of the dignity and kingly qualities of his predecessor, a love of mechanics characterised them both. He built and equipped the Tara Wala Kothi, or observatory, which he placed under the charge of Colonel Wilcox. He was much interested in steamers, then a recent invention even in Europe. So interested was he that he bought and placed upon the Ganges one of these new-fangled contraptions in order to make occasional excursions.

The Bengal Steam Navigation Fund enjoyed his liberal support in return for keeping him informed of current developments. He employed a succession of European artists of note as his court painters, among them Robert Home and George Beechey. The latter was also made Comptroller of the King’s Household. Indeed, Nasir-ud-Din surrounded himself with Europeans wherever possible and was at the mercy of any degenerate rascal who happened to come along so long as he was a European. Chief among these was the notorious barber, de Russet, who was said to have fleeced the King of no less than 24 lakhs of rupees.

Nasir-ud-Din who had no proper conception of his kingly responsibilities cared only for amusements, and his tastes grew more and more degenerate with the passing of time. He took as his chief wife Sultana Boa, the grand-daughter of the Emperor Shah Alam. But when she realised what manner of man he was, she cut herself off from him and lived in seclusion. Another of his wives was a Miss Walters, daughter of George Hopkins Walters, a retired servant of the Company. She held his attention for some years during which she wheedled considerable wealth from him.

She married him in 1827 and died in November 1830. The house in which her mother, then Mrs. Wheatley, and elder sister lived stands to this day within the Residency enclosure where it is known as the Begum Kothi. The elder unmarried daughter was known as the Begum Ashraf-un-Nisa, whilst the younger one who married the King became a Muhammadan and took the name of Jukuddera Queela. Still another woman was raised from the status of an infant’s nurse to that of chief consort. She became known as Malika Jamani, or Queen of the Age, when she married the King. Her son, Kywan Jah, already three years old before she entered the palace by the front door, the King insisted upon nominating as his heir.

The King had originally peculiarly lank straight hair, and not an approach to a curl had ever been seen therein. The barber, de Russet, wrought wonders during a chance visit from Calcutta and the King was delighted. Honours and wealth were showered upon the lucky coiffeur. So much did Nasir-ud-Din come to lean upon him that he trusted de Russet to see that every bottle of wine was sealed in the barber’s house before being brought to the royal table. Before he opened it, the little man carefully inspected the seal to see that all was well. He then opened it, took a sip himself, and poured out a glass for the King.

In the Lucknow museum stands a bronze bust of King Nasir-ud-Din Haider, showing a sensual, almost feminine, countenance with full lips, the whole framed in luxuriant curls, upon which rests a fine massive crown. It is interesting to compare this bust with an earlier portrait showing him with a firmer mouth, his hair short and severely straight, as it was before the ministrations of de Russet.

He wears in both pictures the same ermine robe of state, the same jewelled collar, and the same wondrous chain of gems, and what must be the same crown, although in one or the other it has been carelessly copied, for the details are dissimilar. Animal fights were a fashionable court pastime of the day, especially when the combatants were elephants or quails. The fights of the former took place near the Moti Mahal palace, and those of the latter upon the King’s dinner table after a banquet.

King Nasir-ud-Din Haider had that shrewd cunning often associated with the possessor of a weak intellect. He was quick to see slights whether or not they were intended. On the other hand, he was easily delighted with childish games if he was assured they were popular among European children. Leap-frog took his fancy and, although he collapsed when trying to “make a back” or when he failed to clear a back bent for him, it was not through lack of effort. He had heard from the Englishmen surrounding him about the fox’s brush as a trophy at the end of a run. Not to be outdone, he set his cheetahs coursing after deer. At the end of the chase, having followed on horseback, he secured the tail of a deer, attached it to the front of his cap, and rode home in triumph.

Year by year the power of the barber steadily grew. He could do no wrong in the King’s eyes. Nobody dared gainsay him. But year by year the King grew more capricious and, at last, after a more than usually strong representation from the British Resident, Nasir-ud-Din exclaimed in a fit of rage to de Russet that he had driven away the only good counsellors in the state. The barber saw that his reign of influence was about to end, wisely gathered together all the valuables he could muster and fled from the kingdom into the Company’s territory.