Malnutrition: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Malnutrition: its extent, its effects

Anaemia

2005, 2016

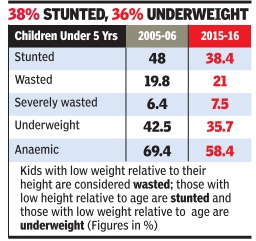

In a stark and chilling reminder of the reali ties of life in India, the recently released fa mily health survey (NFHS 4) results show that over 58% of children below five years of age are anaemic, that is, they suffer from insufficient haemoglobin in the blood, leaving them exhausted, vulnerable to infections, and possibly affecting their brain development.

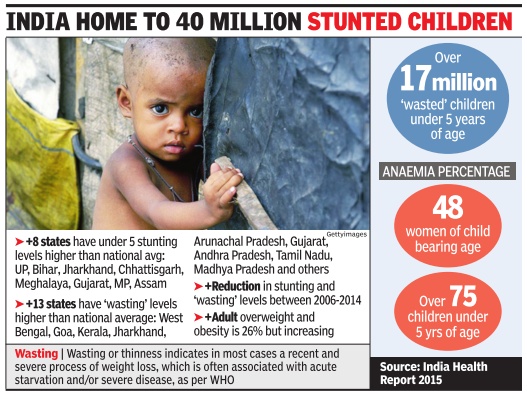

The survey , which was carried out in 2015 16 and covered six lakh households, also showed that around 38% of children in the same age group were stunted, 21% were wasted and 36% underweight. While all the internationally accepted markers of children's health have improved since the last such survey in 2005-06, the levels of undernourishment, caused mainly by poverty , are still high and the improvement too slow.

Based on the 2011 Census data, the total number of children under five in India in 2015 is projected at 12.4 crore. So, around 7.2 crore children are anaemic, nearly 5 crore are stunted, around 2.6 crore are wasted and 4.4 crore are underweight. These numbers are not too different from those in 2005-06. Since popula tion has increased, their share is down.

The World Health Organisation says high levels of these markers are clear indications of “poor socio-economic conditions“ and “suboptimal health andor nutritional conditions“.In short, lack of food, unhealthy living conditions and poor health delivery systems. The WHO defines wasting as low weight for height, stunting as low height for age, and underweight as low weight for age.

The survey also found that just over half of all pregnant women were anaemic. This would automatically translate into their newborn being weak. Overall, 53% of women and 23% of men in the 15-49 age group were anaemic.

There is wide variation among states. The data for UP has not been released in view of the ongoing polls, according to Balram Paswan, professor at Mumbai-based International Institute for Population Sciences which was the nodal agency for the survey done for the health ministry . But poorer states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Assam, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh have higher than national average rates on all markers.

More advanced states like those in the south, Haryana and Gujarat have slightly better numbers but are still at unacceptable levels. In Tamil Nadu, 51% children are anaemic while in Kerala it is over one-third. In many states, stunting has declined but the share of severely wasted children has increased. These are clear signs of an endemic crisis of hunger in the country that policy makers don't appear to be addressing.

2017: India at bottom of table

Women's health in India is facing a serious nutritional challenge, with the country on the one hand grappling with the largest number of anaemic women in the world and on the other having to deal with diseases linked to obesity which is rapidly increasing among the fairer sex.

Findings of the new Global Nutrition Report 2017 place India at the bottom of the table with maximum number of women impacted with anaemia in the world, followed by China, Pakistan, Nigeria and Indonesia. In India, more than half (51%) of all women of reproductive age have anaemia, whereas more than one in five (22%) of adult women are overweight, according to the data.

The report analysed the situation in 140 countries against targets set in May last year at the World Health Assembly (WHA) held in Geneva.

Experts say that while the government has started to recognise the problem of anaemia and under-nutrition in women, India has made no progress in addressing it as there are too many gaps. The report highlights that the country presents worse outcomes in the percentage of reproductive-age women with anaemia, and is off course in terms of reaching targets for reducing adult obesity and diabetes.

In 2016, the report showed that nearly 48% of women in India were anaemic. India's government is recognizing that the country can not afford inaction on nutrition but the road ahead is going to be long. The Global Nutrition Report highlights that the double burden of undernutrition and obesity needs to be tackled as part of India's national nutrition strategy . For undernutrition, especially, major efforts are needed to close the inequality gap“ said Purnima Menon, senior research fellow in the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)'s South Asia Office in New Delhi.

Doctors say mere undernutrition is not the cause for high anaemia burden in India.“Only nutrition cannot address the problem. Poor hygiene is a major cause for anaemia because it prevents absorption of nutrition,“ said Dr Indu Taneja, senior consultant, obstetrics & gynaecology at Fortis Escorts Hospital.

Low awareness, illiteracy and the practice of putting the family before self when it comes to care are factors that often deter women in India from taking proper nutrition and care for themselves leading to anaemia, says Dr Taneja. “The impact can be severe at times, especially when it happens in the child-bearing age,“ she said. Anaemia among women in the reproductive age often leads to health issues in the mother as well as the child. While such women are prone to infection and my need blood transfusion during pregnancy , chil dren borne of such women often remain under-developed with poor immunity .

However, the report points out anaemia is a global issue that many women in high income countries also suffer from. The report pegs the prevalence rates in countries like France and Switzerland at around 18%.

Globally, 614 million women aged 1549 years were affected by anaemia. The report found `significant burdens' of three important forms of malnutrition used as an indicator of broader trends childhood stunting, anaemia in women of reproductive age and overweight adult women.

In India, latest figures show that 38% of children under-5 are affected by stunting and 21% of under-5s are defined as `wasted' or `severely wasted', meaning they do not weigh enough for their height. The report found the vast majority (88%) of countries studied face a serious burden of two or three forms of malnutrition. It highlights the damaging impact this burden is having on global development efforts.

Child malnutrition

2006- 2014: Child malnutrition declines, but still very high

The Times of India, Dec 11 2015

Malnutrition down, but not enough

Child malnutrition in India has declined but continues to be among the highest in the world. Between 2006 and 2014, stunting levels in children under five declined from 48% to 39% as compared to global level of 24%, the India Nutrition Report says.

Being stunted means that the affected children are not fulfilling their potential either in childhood or as adults and their brain and immune systems are compromised, often for their entire life, the reports says. However, there has been an increase in the decline rate of stunting at the national level. “Though India's national rate of stunting decline has increased from 1.7% in 200506, to now 2.6%, it is not fast enough,“ said Lawrence Habbad, senior researcher from International Food Policy Research Institute. A global report assessing India's performance vis-à-vis 193 countries concluded that India was on track to meet only two of the eight global targets on nutrition though it had significantly improved its performance in the past 10 years.

The India Nutrition report and the Global Nutrition Report was released by Union ministers J P Nadda and Maneka Gandhi on Thursday .

Nadda urged for suggestions to accelerate action at state level and strengthening and accountability for impact of nutrition programmes.

In order to strengthen the ICDS programme, women and child development ministry has been undertaking capacity building measures for Anganwadi workers equipping them with tablet devices and giving them promotional abilities, Gandhi said.

Diabetes and poor food habits

Indians' poor food habits fuelling diabetes

The Times of India, Nov 06 2015

Malathy Iyer

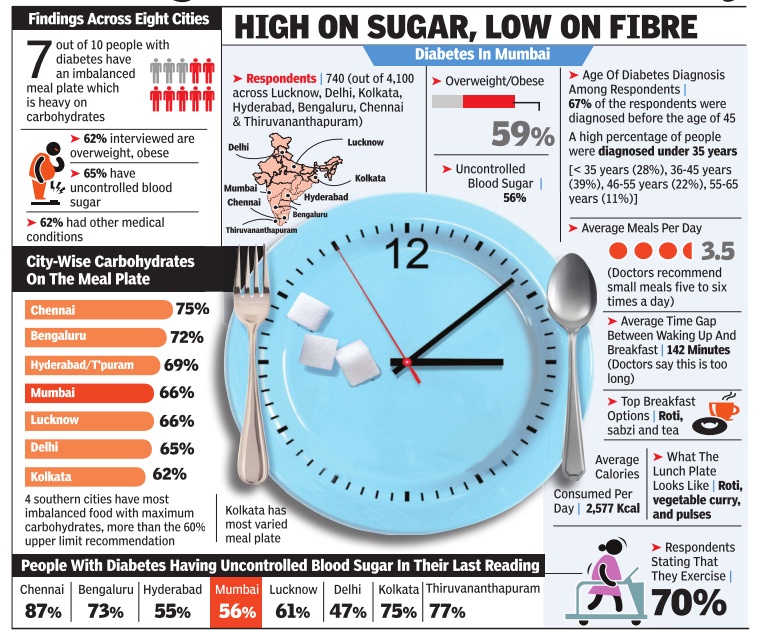

Indians' poor food habits fuelling diabetes, finds survey What Indians eat and how could be fuelling the dia betes epidemic across the coun try, suggests a new survey that interviewed 4,000 diabetic pa tients across eight cities. The main culprit could be the Indian craving for rice, fine flour rotis or upma -all carbo hydrate-based foodstuff high on calories but low on muchneeded fibre. “Rice accounts for 48% of the daily calorific intake of most Indians, said endocrinologist Dr V Mohan from Chennai.

Considering that most types of white rice rapidly increase the blood sugar levels, caution is advised.

But urban Indians who suffers from diabetes seem far from cautious. The new survey , titled Food, Spikes and Diabetes Survey, showed seven out o f 10 people with diabetes in urban India paid little attention to what and how much they eat.Carbohydrates are supposed to comprise only 60% of the plate, but 70% of those surveyed in Mumbai and 84% of those in Chennai consumed more.

There is also a problem with how Indians eat. “Indians tend to eat so fast that the pancreas struggle to produce adequate insulin for metabolising the food, said Dr Shashank Joshi, president of the Indian Academy of Diabetes.

Indian diabetic patients also fail to observe healthy gaps between meals, said Dr Joshi.

Protein deficiency

In 6 major cities, 2017

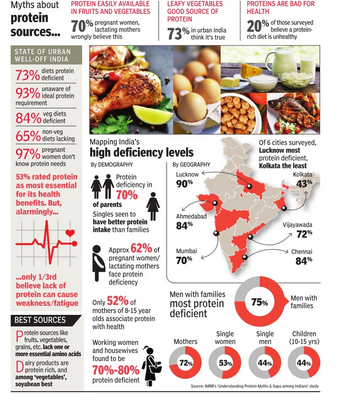

73% OF URBAN RICH INDIA IS PROTEIN DEFICIENT|Jul 27 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

Large sections of Indians cannot afford a balanced diet. But what makes the urban rich follow diets that are low on protein? An IMRB survey reveals the high levels of protein deficiency among the well-heeled and the protein myths they believe.