Gujarat: Political history (1945- )

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Agitations

The Times of India, Aug 30 2015

Protests by the privileged? Gujarat has a long history

Economics is the common thread that runs through agitations in the state over the last 75 years, finds Amrita Shah Gujarat has a vivid recent history of large, anarchic agitations. Observers are often surprised to hear this, pointing to the state's association with Gandhi and its reputation as a highly developed region with a strong entrepreneurial drive as reasons why this should not be so. Those familiar with the state's peculiarities, however, suggest that Gujarat's relationship with violence in fact stems from these particular characteristics rather than existing despite them. It has been proposed, for instance, that Gandhi's legacy of agitation has contributed to present-day violence in the state. Historian Howard Spodek describes the “two parallel springs of mobilization and institutionalization“ which he believes Gandhi successfully controlled, and speculates that the future could go either way: that new organizations could succeed Gandhi to restore a balance or that the local and the national arena could decline becoming accustomed to deepening levels of violence.

Those who expect a pragmatic, business minded society to be above turbulence are similarly mistaken because economics, far from quelling, has invariably been a key motivating feature for mass violence in the state. A survey of prominent agitations over the last 75 years suggests a common thread.The vigorous participation of Gujaratis in the Quit India movement of 1942, for instance, while it owed much to the intense nationalistic fervor prevailing at the time, was also partly enabled by fears that the British, following a scorched earth policy would destroy local mills to prevent them from falling into the hands of their World War II rivals, the Japanese.

The movement for a separate state in the 1950s was waged on the rhetoric of language and regional pride but was also underpinned by a feeling of neglect by successive Congress ministries. According to Achyut Yagnik and Suchitra Sheth's The Shaping of Modern Gujarat, the absence of any major project on the area's rivers in the First Five Year Plan coupled with the perception that resources were being diverted to Marathispeaking areas culminated in the Mahagujarat movement.

In 1974 rising mess bills in an engineering college in Ahmedabad sparked outrage among students, snowballing into a statewide stir known as the Navnirman movement, an agitation in which even housewives joined in by beating thalis at a prearranged hour. Anxiety over shrinking job opportunities due to the expansion of caste-based reservations led to ugly riots in 1981 and in 1985.

These iconic mass agitations have not involved the poor and the working class but have been led by members of the upper and middle castes and classes, with students playing a pivotal role. In the 1985 anti-reservation riots even children, encouraged by their parents, boycotted school.

Middle class leadership brought a managerial flair to mass agitations often marked by a high level of organization, a clever use of communication technology and marketing gimmicks.This is not the place to explore the links between an emerging middle class solidarity and the growing popularity of the Hindutva movement but it can be said that mass agitations tended to articulate the grievances of and sought to expand economic opportunities for those in the middle and upper reaches of society , sometimes resisting the advancement of those below. For instance, the 1981 and 1985 anti-reservation riots (a precursor one could say to the current fracas) saw attacks by assertive Patels selectively on upwardly mobile sections of the lower castes.

Mass agitations have also enabled dominant groups to bypass inconvenient politics. The unseating of chief minister Chimanbhai Patel in 1974 provided an early taste of power. Madhavsinh Solanki, a backward caste chief minister who won a resounding majority a decade later with a formula that united underprivileged sections of society including Harijans, Adivasis and Muslims, was forced out of office within months by massive protracted violence.

The latter's history of truculence is surprising more so in light of political scientist Nikita Sud's claim that Gujarat's development trajectory , which ensured the rise of agrarian capitalists and rapid urbanization after 1960, has been skewed in favour of dominant castes and classes as has the contemporary economic liberalization process.

In many ways then, the current agitation by the influential Patel community is in keeping with the state's past experience of violent protest by the privileged. But while the agitation may have its origins in the local, and Gujarat-based observers have provided various cogent explanations for the sudden discontent, there is something about the scale and deliberate theatricality of the event that points to a less definable intent. A charismatic leader, surging crowds, speeches in Hindu rather than Gujarati, the dramatic destruction of public property , seem to be elements of a spectacle aimed at creating a mood as much as or rather than stating a demand. The atmospherics need to be watched.

Caste combinations

2014 and 2016: Socio-regional profile of Chief Ministers

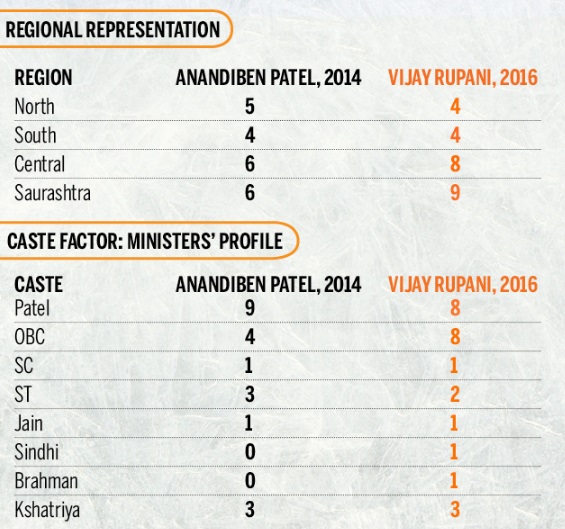

See graphic, ‘Socio-regional profile of Chief Minister in Gujarat, 2014 and 2016’

KHAM (Kshatriya, Harijan, Adivasi, Muslim)

BJP warns Patels, says Cong trying to short change them | Oct 25 2017 |The Times of India (Delhi)

The `KHAM formula', helped Congress bag 149 of the state's 182 seats in 1985.

The brainchild of the then CM Madhavsinh Solanki, KHAM -a combination of Kshatriyas (OBCs included), Harijans, Adivasis and Muslims -proved a successful experiment to forge an unbeatable alliance that enveloped nearly 70% of Gujarat's population. It excluded Patels and other upper castes who deserted Congress en masse. That didn't matter though, as Solanki went on to set an electoral record that stands to date. The BJP has long banked upon support from the upper castes.

Significantly , KHAM also led to Congress' downfall as it was not able to keep the combination intact since it had been tried for the first time.In 1990, the Chimanbhai Patel-led Janata Dal weaned away most Patel votes and formed a coalition government with BJP. It fell apart mid-way after the Babri demolition, and Congress was happy to help Chimanbhai and remain in power as a secular coalition. Since 1995, BJP has won all the five assembly elections, although they had to lose power once due to the Shankersinh Vaghela-led rebellion that Congress again cashed in on.

BJP's ascent and ability to stay at the top was rooted in the deep inroads it made by doggedly working among the Ksha triyas, OBCs, Dalits and Adivasis under the `Hindutva' umbrella to break up `KHAM'.All this, while keeping its Patel and upper caste vote bank intact. Modi himself made conscious efforts to prop up a fresh leadership from among KHAM constituents.

Muslims in Gujarat elections

2017: Gujarat’s Muslims out of poll picture

HIGHLIGHTS

After 2002, the community has turned inwards, focusing on education and trying to rebuild businesses

Gujarat’s Muslims are completely ghettoized across riot hit cities like Vadodara and Ahmedabad

Dr JS Bandukwala, former Physics professor at MS University, has always been the face of dignity in the face of immense personal suffering. He lost his home when it was attacked by mobs during the 2002 post Godhra riots, his long time neighbours slammed doors in his face, he was shunned by his university colleagues and made a victim of a witch-hunt. Yet Bandukwala is marked by a singular lack of bitterness and today runs a charitable educational trust for Muslim youth. While the 2002 riots were once a volatile issue in Gujarat polls, in this election the riots are a non-issue and Gujarat's ten percent Muslim community as a whole is invisible in the poll. "Muslims are isolated and have been made politically redundant," says Bandukwala, "but our irrelevance is not a bad thing. We are being left alone even though Modi fights elections best when he makes Muslims the target. Modi needs a Muslim target, but this time the Gujarati Muslims are lying low."

So have Gujarat's Muslims grown numbed by the attacks on them and do they not raise their voices anymore? "Muslims are keeping their cards close to their chest and keeping quiet," says businessman Zubair Gopalani. "We are teaching our community to turn away from hate, to love Hindus as our brothers and work for development."

After 2002, the community has turned inwards, focusing on education and trying to rebuild businesses. "We are keeping quiet, doing our work and being happy in our irrelevance," says businessman TA Siddiqi. "Neglect is good, all we ask is humko chain se jeene de." Feroze Ansari and Pervez Misarwalla are IT professionals who have started a group called Rising Indians to bring Muslims into the mainstream and train them in leadership skills. However they're hurt by government discrimination. "When we do public spirited works like provide water to traffic police in summer, the government does not send us certificates the way they do with Hindu bodies," says Ansari.

In the Muslim locality of Tandalja many complain about lack of infrastructure, schools and playgrounds. Recently 1800 hutments were demolished here. "The police still comes and picks up innocent Muslim youth on flimsy charges," says shop-owner Imran Patel.

Gujarat's Muslims are completely ghettoized across riot hit cities like Vadodara and Ahmedabad. Rich and poor cluster together in designated localities, the Disturbed Areas Act preventing Hindus or Muslims from buying property in each others' areas without the permission of the administration. Pointing to the fact that many private schools refuse to take "M class" students, Pervez Misarwalla of Rising Indians believes Muslims need to create their own schools and colleges. "Across UP and Maharashtra there are many Muslim institutions, but almost none in Gujarat." He adds that there are many Muslim IAS and IPS officers in Gujarat but they are sidelined and marginalized.

In the Muslim area of Tandalja, posh bungalows adjoin slum colonies, multi-storied buildings share walls with low cost housing. "My daughters get upset when they hear the bad language being spoken in slums next to us, but we have no place to move to," says Siddiqi. Yet many say things have changed for the better. "2002 was a blessing for Muslims in a way," says entrepreneur and educationist Saira Khan. "Muslims gave up on liquor trade and other such activities and turned squarely to education. Today for Gujarati Muslims its education, education, education. That's our focus."

How do Muslims feel when BJP leaders continue to target them in speeches? "We feel hurt," says Bandukwala, "but we are so used to it by now. In this election Muslims are keeping quiet and refusing to be provoked even when threatened." "We counsel our community not to act in rage, not to hit back, because this only inflames the situation," says Gopalani. Counters Imran, "But if they misbehave with my Muslim sister should I just sit back and take it?" Counsels Siddiqi. "Lets use the courts, use the police, Ek chup, sau balatali: One moment of silence can solve a lot of problems."

Interestingly, the Congress too has chosen to stay silent on any issue which might flare up a Hindu Muslim tangle. "The Congress talks of looking after our interests but in reality they are much too scared to raise their voice. It's now all about who gets the Hindu vote,' says engineering student Pervaiz Sadiq.

Only 2 Muslim MLAs were elected in the last assembly elections of 2012 and for decades a Gujarati Muslim has not been elected to Parliament. But Muslims here say they prefer a peaceful irrelevance, than a potentially conflictual struggle for political space. Gujarat's post 2002 ghettoisation is complete.

Growing irrelevance of Muslim vote

On the the eve of the first phase of voting in Gujarat, Election With Times travelled to what is believed to be the oldest mosque in India: the Barwada Juni Masjid in Ghogha in Bhavnagar.

The mosque is said to have been built by Arab traders in the Prophet's time and is the only mosque whose mehrab points towards Jerusalem, as per the tradition in the Prophet's early years. In contrast, all the mosques built later point towards Mecca as per the Prophet's directions.

Election With Times: In this special episode from Juni Masjid, we discuss the growing irrelevance of the Muslim vote in Gujarat. Muslims constitute 9.67% of the Gujarat electorate and remain pivotal in 30 out of 182 assembly seats. However, like in UP, BJP is not fielding any Muslim candidate in the upcoming elections. On the other hand, Congress will field 6 Muslim candidates (1 less than in 2012).

The BJP did not acquiesce to the Minority Morcha's demand for Muslim candidates in six seats (Jamalpur-Khadia, Vejalpur, Vagra, Wankaner, Bhuj and Abdasa).

In fact, BJP has fielded only one Muslim candidate for assembly polls (in 1995) in Gujarat since 1980. Abdul Gani Kureshi contested as a BJP candidate from Vagra in 1995 and lost to Congress by 26,439 votes.

Yet, BJP fielded 325 Muslim candidates in 2010 panchayat and municipal polls: 245 of them won. BJP also fielded 450 Muslim candidates in 2015 panchayat and municipal polls.

Muslim politics in Gujarat has evolved in the last decade, with many Muslims also supporting BJP, but low Muslim representation relative to their population share in Gujarat's electoral politics continues to raise questions.

Voting patterns

1990-2012: urban areas vote BJP

From: Himanshu Kaushik, Gujarat cities appear to be impregnable BJP fortresses, November 26, 2017: The Times of India

The ruling BJP has maintained a complete domination over urban seats in eight municipal corporation areas of Gujarat since 1990. While there were in all 28 such seats till 2007, post-delimitation these increased to 39 in the last elections in 2012 — when BJP won a whopping 35. The Congress won only four — two in Ahmedabad and one each in Jamnagar and Rajkot.

Even in 1990, when the party contested just 143 seats out of a total of 182 seats in the assembly, BJP won 18 seats. Congress slide in urban Gujarat in fact began in 1990, when it bagged just four seats — with seven seats going to Janata Dal. The best performance by Congress in the last six elections for the city vote was in 2007 when it managed six wins.

The increase in seats post-delimitation was due to growing urbanisation and expansion of boundaries of some of the municipal corporations — Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Surat, Rajkot, Jamnagar, Bhavnagar, Junagadh and Gandhinagar.

There are reasons to believe that if BJP wins a majority in 2017, it will be because of wins in the eight big cities of Gujarat. BJP presently rules all eight municipal corporations.

In 2015, when civic body polls were held across Gujarat, BJP ceded ground to Congress in the zila and taluka panchayats, as also the municipalities, but gave its best ever performance in the municipal corporations. This, despite the violent Patidar agitation for quota having begun well and truly.

BJP spokesperson Yamal Vyas said, “Our party has a strong urban presence because we had a good workers base in cities since 1990.”

Congress spokesperson Manish Doshi said, “We are raising urban issues but we need to focus more on booth management in cities in Gujarat. Even Rahul Gandhi has had a number of interactions with doctors, lawyers and businessmen.”