Museums: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Early 21st century museums

Experiences, rather than objects

Spaces like the country's first Partition museum in Amritsar, the Remember Bhopal museum for social justice and the Conflictorium in Ahmedabad are organised around experiences and emotions rather than objects

All these years, the Partition of India and Pakistan, the biggest mass migration in the 20th century , has been confined to refu gee accounts and nightmares, literature and cinema, and lived on in the fears and longings of later generations. There was no physical memorial anywhere to Partition -perhaps because it was seen as too flammable, too painful.

Now, 70 years on, a small museum in Am ritsar's Town Hall marks the traumatic event which led to 12 million people crossing the border, and killing somewhere between one and two million.

“It's a people's museum,“ says co-founder and CEO Mallika Ahluwalia. “It's not about assigning blame, but to acknowledge the experience of those who lived through it.“ It is their voices and memories that echo in the four rooms of the museum currently open for viewers. In one of the rooms, an installation of a well is a quiet reminder of the violence, rape and honour killings of women.At another point in the room, a still-brilliant Phulkari coat and a battered leather briefcase tell a painful love story .

The Partition Museum is still very much in beta -it will open all its rooms to the public on August 17. While the material first came from the personal networks of its founders and trustees, Kishwar Desai, Dipali Khanna, Bindu Manchanda and Ahluwalia herself, all from Partition-affected families, she says they were overwhelmed with the stories that poured in. The museum's visitor's book has others offering more personal accounts. “We want to do an oral history archive, one where anyone can come and search, perhaps hear their great-grandparents' voice,“ says Ahluwalia.

The Partition Museum is one of several memory museums that have sprung up around the country. They flip the logic of traditional museums, where you go to look at objects and exhibits -here, the objects are made meaningful only because of the events and experiences they emerge from. The Remember Bhopal museum is about the survivors of the 1984 gas tragedy telling their own story, in sharp counterpoint to official versions. “The museum is not meant to evoke pity or anger alone, but also their ongoing protest, their fight and resolve,“ says museologist and journalist Rama Lakshmi, who curated the museum. The objects are not showpieces -they include the inhaler of a woman with respiratory illness who marched all the way to Delhi, the bangle broken when an activist was jailed.Rusted locks and corroded utensils speak of the damage of the gas tragedy, the betrayal of its survivors.

The Conflictorium museum in Mirzapur, Ahmedabad makes a more oblique point about the conflicts and differences that make us. There is no explicit mention of the 2002 riots, but the museum calls for an examination of political, social and personal conflict. A room with the silhouettes of leaders like Gandhi, Ambedkar, Nehru, Jinnah, Sardar Patel and Indula Yagnik, with red lines running between them, is also a reminder that these figures and their thoughts were often in argument and opposition. “These criss-crossings exist, and they're fine. That's the beauty of the Union of India, that there is no coherent idea but many thoughts that collide and come together,“ says Avni Sethi, founder of the museum.

None of these museums are encyclopaedias pinned to the wall, or storehouses of objects -they are meant to make you feel, to engage the senses and the imagination. “There are 22 museums in Ahmedabad, and hardly anyone visits, so why another one? Maybe we're not a museum-going culture, maybe we're more oral and tactile. So we did away with traditional museum etiquette. There are no yellow lines or glass boxes, you can touch and feel and add and subtract to the displays,“ says Sethi. The museum is not about the exhibits alone -it's a dynamic space, with movie screenings, poetry readings and stand-up gigs.

“In India, we've only known the British model of collections exhibited like trophies, a sculpture gallery, a numismatics gallery and so on. We need more storytelling in museums,“ says museum designer Amardeep Behl. For that to happen, historians, designers and storytellers must first think together, then get the specialised curators in, he says.“One needs to create immersive experiences to trigger emotions. It's about the design, rather than the technology or the text,“ says Shekhar Badve, who has designed the `Swaraj' museum in Pune dedicated to early freedom fighters, among others.

The day the Bhopal museum opened, one of the women cried for hours in front of her own infant son's frock in a display case, says Lakshmi. She had donated it to the museum herself, not so long ago, but something about seeing it aestheticised, lit up, with his picture and her voice telling the story, just devastated her. Many of the survivors are taken back to their own experience that awful midnight, in the pitch black of the first room in the museum.

The last room in the Conflictorium has a “map of feelings“ with hooks where you can place bangles, to describe your own complicated responses to each exhibit. “We don't want the visit to be input-input-input, you want people to pause and process,“ says Sethi. Those with direct memories of events are often overwhelmed in these museums, but it can unsettle other visitors too. In the Partition Museum, the gallery of hope features a tree where people write messages on paper leaves, and many of those are jingoistic “East or West In dia is the best“, “Salute to our sol diers“ and so on, while a few are more reflective, moved by what they just saw.

Of course, these museums are still new and few, and have to walk a careful line. “Muse ums can be a space of genu ine reflection on conflict only if they are truly au tonomous. The British Mu seum can host a discussion on the Middle East only because the government keeps a distance.In India, it's harder for museums, public or private, to take on contentious political subjects,“ says Ruchira Ghose, former director of Crafts Museum. There's a twee quality that often creeps in when complex confrontations of trauma are ruled out, says art critic and curator Ranjit Hoskote. “In a society that is afraid of confronting its own spectres, there are limits to what a memory museum can do,“ he points out.

Egyptian mummies

Kolkata

Prithvijit Mitra, 4,000-yr-old Kol mummy to get new lease of life , Dec 25 2016 : The Times of India

One of the most enduring attractions of the historic Indian Museum -the 4000-year-old Egyptian mummy that had been shipped to Kolkata in 1882 -is set to be restored in Mumbai.

Displayed at the museum's Egyptian gallery , the mummy is placed inside an insulated cabinet, which, the museum authorities claim, has prevented its degeneration. But the gallery needs immediate renovation and the mummy could be preserved better with inputs from experts, they admitted.

“It rests inside an insulated cabinet which has a micro-climate of its own. The mummy is in no way exposed to the atmosphere, so it has not been affected. But the gallery needs to be repaired now as it had been left out of the bicentenary renovation work two years ago,“ said Jayanta Sengupta, director.

Wrapped in cloth with arms tied down to the sides, the mummy looks fragile.The flesh of the face and the head has crumbled away , leaving the bones exposed. The mask has been taken off and laid on the chest.

The mummy was a gift to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, which founded the museum, from a British officer, Lieutenant EC Archbold of the Bengal Light Calvary , in 1834, according to the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

“The mummy was obtained with some difficulty from the tombs of the kings at Gourvah,“ the society reported in its minutes. “The native crew on board the ship ... having objected to receive the mummy in his baggage, he had been under the necessity of requesting one of the officers of the Sloop of War Coote to bring it onward to Bombay , whence it will be forwarded to Calcutta by the earliest opportunity .“

Incidentally , India is one of the few countries that houses Egyptian mummies in six different museums. Very few museums outside Europe and America possess mummies from Egypt.

The museum was the only one in India to have held an exhibition of mummies a few years ago. “They had organised it jointly with the British Museum, which is an authority on mummies and their conservation. Even though we believe that the Kolkata mummy is fine, they might be able to spot flaws in conservation and recommend measures to make it last longer,“ said Sengupta.

The Indian Museum director added that the mummy is bound to have suffered degeneration in the early years when preservation methods were non-existent. “It is bound to have undergone some wear and tear then. But ever since it was placed inside the protected cabinet, it has been wellpreserved. Or else, it would have disintegrated,“ he claimed.

Living Museum of Urur-Olcott Kuppam

Chinki Sinha , An equal music “India Today” 8/5/2017

In Poramboke, which means land outside the purview of assessed land records, Magsaysay awardee T.M. Krishna sings "it is not for you, nor for me, it is for the community, it is for the earth". It sums up his choice of "unusual locations", like the living museum that is the fishing hamlet of Urur-Olcott Kuppam, to start what he called conversations in 2014 in a bid to democratise Carnatic music. To take it to the man whose ear it had not fallen on thus far. To the people who could not afford his ticketed concerts. For them, he would sing, in the mornings.

"I see it as a metaphor for possibility," says Krishna. "We remain isolated. How can we listen and talk?"

Krishna recounts an incident over the phone. "I first heard it at the festival (the vizha that Krishna conducts every year in the village). I was walking through the bylanes of the village asking people to come to the performance space when I heard it." He is talking about the paraiattam, a form of drumming traditionally associated with funerals. But it is actually about caste, which extends to ritual, food, attire, even music. So the mridangam, thavil and parai are not mere musical instruments but representations of the caste hierarchy. All are made of animal hide-mridangam from goatskin, thavil from buffalo skin on one side and goatskin on the other and parai from cowhide. And in the prevalent social order, the mridangam, presumed to be a divine instrument, was the preserve of the upper castes, the thavil of the intermediate castes and parai of the Dalits. "The drumming," says Krishna, "is loud and passionate and you have to dance to it. If a person does not dance or move his body to the beat of the parai, he is presumed to be dead, they say."

He danced to it. When he heard it first, on the street, and later on the stage, at the end of the festival.

(Sexualised) Museum of Unbelonging

Chinki Sinha , Collectors Additions “India Today” 8/5/2017

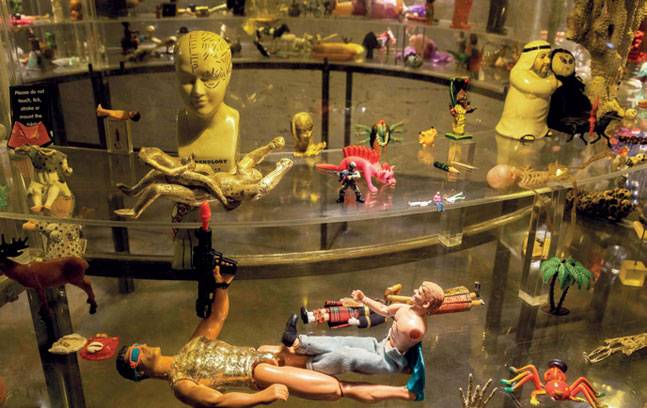

Her first baby was Jack. He wears tattered clothing and was a doll she shared with her sister Mou, the one whose name the Museum of Unbelonging (MOU) echoes. "We had Jill too," says Mithu, "but she died in an operation. My sister told me not to give Jack to anybody." Part of the much-acclaimed curated project-After Midnight: Indian Modernism to Contemporary India 1947/1997-at the Queens Museum in New York in 2015, it described Sen's work thus, "Displayed as a phantasmagoric fantasy, the work comments on the duality of eroticism, charged both with control and liberation."

"Our hearts are museums of memories," says Mithu. And so there are deities, a dog mating with a human, a terracotta man with a large phallus, puppets, a seahorse with a curled tail, a pair of binoculars, hair clips, a stuffed liger and a leopard, a black rose, white rose...

She calls the objects in her museum her babies. They are a cataloguing of her emotions, and emotion, as the great French philosopher Gaston Bachelard said, "is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost". Mithu has always seen herself as "near poets" rather than "near historians".

So her museum is a carnival, a celebration, an imaginary world. One in which there are no forevers. She gives away her babies and finds new ones.

Museum of collectibles from home and the universe

Chinki Sinha , The boat and other things “India Today” 8/5/2017

I don't think about what I collect. I just collect," says artist Subodh Gupta. Like the root he bought in Kochi or the figurine in a little antique store. A gold-plated potato, used utensils, entire kitchens bought from slums, boats but no river, and statues and figures from his native Khagaul in Bihar and elsewhere.

He has built massive structures in steel and brass, played around with cowdung. The associative power of his works is what gives them the scale they have attained.

He might buy his utensils in wholesale markets, but they have lost their particularity. There is rural and global, nostalgia and industrialisation. You can capture the tension only if you have had that prolonged struggle with self and identity.

Yet, he won't indulge you with a narrative. The art must be abstract at all costs. His abstraction is bent on drawing out the essentials, almost squeezing them to communicate the intangible.

All his life he had wanted to get away from the small railway town where he grew up. He escaped finally, only to find the past informing everything that he does in his present.

"I started my work with whatever I had seen in my childhood," he says. "Who knows who we are? Our mind has so much power. We are holding everything within us."

His museum is a liminal space. It has everything from the past that is getting transformed into the future. Like the book of recipes where he is currently documenting the memory of food.

"I find my planet on my plate," he says. He is in communion with his universe that is a collection of objects soon to be lost to history. Like the mixing bowl in his studio. Cast in stone, it has a red and white chequered cloth, a gamcha, and kneaded dough. It sums up the churning of the universe in a utensil, the turbulence, the thickness of identity, the malleability of form and shape. And yet it is as simple as saying it is part of where we come from.

"It is part of us. A memory. An ongoing thing of archiving which is so fleeting," he says. Memory has poetic licence. It goes back and forth, it edits and reconfigures. His museum then is a nostalgist's landscape.

Museum of Partition

Chinki Sinha , A space for healing “India Today” 8/5/2017

When she began asking people to share their stories of Partition and give her one object that they had brought with them, Kishwar Desai, a writer and an artist, was trying to archive the biggest migration in history for which there are written records and photographs but no artefact. Coming from one such family, she remembers how her grandfather never spoke of things left behind. Or even the pain. There had to be a space for catharsis where people could share their own experience of Partition and help personalise its history.

Like the phulkari coat Pritam Kaur Mianwali, then 22, brought with her when she fled from Gujranwala. "When Pritam Kaur crossed the border with a bag slung across her shoulder she had just this phulkari coat among her few precious possessions-a small comfort in her traumatic sojourn, and a reminder of happier days." Likewise, Bhagwan Singh Maini, then 30, carried with him a leather briefcase that held his degrees as well as his property documents. They got married in the refugee camp in 1948. "These (the coat and the leather briefcase) are a testimony to the life they lost, and found, together," says Desai.

The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TAACHT), which is housed in the 150-year-old Town Hall in Amritsar, is a repository of art, artefact, documents and oral histories. Opened in October 2016, it is spread across three rooms and will eventually have seven galleries across 16,000 square feet. There will also be a gallery of hope. "That's why this museum is there. To heal," says Desai.

Museum Bhavan

Chinki Sinha , The mother of museums “India Today” 8/5/2017

Spaces within spaces. museums within museums. Compact and foldable, they are entire worlds in themselves. Together, they are a vast realm of memories going back to 1981, when she started photographing.

And so there is a Museum of Little Ladies and a FileMuseum, a Museum of Men and the Museum of Photography, Museums of Factories, Furniture and Vitrines, as well as a Museum of Chance.

Dayanita Singh's Museum Bhavan is a mother museum, holding within it nine smaller museums. Her museums give birth to other museums. But she is quick to add that they aren't mating.

Her journey began by asking herself the question: could the museum itself be not just a venue, but a form in itself? "I am making museums as a form and architecture," she says. "My work is so much about the dissemination and opening and closing of structures, adding and removing objects."

Arranged in clusters, her museums act as screens. Folded, they are immersive spaces where you can pull out a stool and lose yourself in time. Open another, and you might find a table and two stools, with no backrest. So that you can lean in, and listen to the other.

For her most recent Museum Bhavan, Dayanita has as her raw material 800 photographs. Each structure has 140 photographs inside it, but only 40 can be displayed at any given point.

Her mother's bedside drawer was always full of things. It was my personal museum of clips, says Dayanita. "My house was full of albums. To me, you printed a photograph to make something. The book was an obvious format. My mother would tell me that someday these photographs will be of tremendous importance. A photograph is when a lot is left unsaid." But then if you are a poet or a dancer, it opens up incredible and infinite possibilities.

She is interested in events unfolding outside the frame and in pictures interacting with each other to form part or whole of a narrative. She doesn't believe in captioning her images. Facts limit the scope of a picture. Place it in another context, and you can have a million other narratives, a million other chances.

Next on her agenda is a pocket museum. She already has a suitcase museum.