Euthanasia: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Supreme Court guidelines on Euthanasia

The Hindu, May 23, 2015

Active euthanasia : Administering of lethal injection to snuff out life is illegal in India Parents, spouse, close kin, "next friend" can decide, in best interests of the patient, to discontinue life support. The decision must be approved by a HC.

In dealing with such a plea,

» Chief Justice of High Court must create a Bench of at least 2 judges to reach a decision.

» Bench must nominate three reputed doctors

» A copy of the doctors's panel report must be provided to close kin and State govt. Only then can verdict be reached.

Passive euthanasia : Withdrawing life support, treatment or nutrition that would allow a person to live, was legalised by way of SC guidelines in 2011.

Mercy killing: Prevalent in parts of Tamil Nadu

The Times of India, May 24 2015

Padmini Sivarajah

Thalaikoothal

Mercy killing is illegal in India, but in parts of Tamil Nadu, it is alive in the form of a gruesome tradition

A very crude form of `mercy killing' still survives in some villages in south India.Here, people take it upon themselves to `cull' elderly persons who are bedridden and considered a burden to the family , with something as innocuous as oil and coconut water. And though villagers claim they've buried the gruesome tradition, social activists say they haven't seen the last of it yet. “We no longer do it, but it was called `thalaikoothal',“ says G Anusha of Innam Reddiarpatti in Virudhunagar district. “ A person who was suffering and bedridden was given an oil bath at dawn and then plied with multiple glasses of tender coconut juice, which resulted in the body cooling considerably , eventually causing high fever. In a day or two they died,“ she says, insisting that the practice has now dwindled. Her neighbour Kuruvamma credits improved facilities like transport and medical support for the decline of the tradition. “I myself look after two elders in the family . We want them to live as long as they are destined to,“ she claims.

Seventy-five-year-old, bespectacled Sankaramma sits rolling paper tubes for a fireworks factory . “I have to work as long as I can to be able to eat,“ she says, insinuating that she literally has to safeguard her living. But then she cautiously mentions that she has known elderly people who were given thalaikoothal deaths. “But that was then, she hastily adds.

Is this staunch denial really an eyewash? A social activist from Usilampatti, M P Raman, concedes that this indigenous form of mercy killing still prevails, but is kept under wraps for fear of prosecution. His words are echoed by C Radhakrishnan, senior manager at Help Age India, Madurai. “Though villagers claim it isn't practiced anymore, thalaikoothal is more prevalent now than ever before,“ he states, citing greater employment as one of the reasons. “Unlike those days when at least one member of the family was at home to look after the elderly, everybody in a household today is employed and a bedridden person becomes a big responsibility,“ he explains.

Apparently thalaikoothal is no random act of extermination, but a well-oiled death ritual provoked by poverty and abetted by custom. An old, ailing individual, with an already weakened immune system is pushed over the edge with oil baths and coconut juice guaranteed to induce a fever that will eventually do the person in. And even as preparations for the thalaikoothal are under way , family will start arranging for the funeral as well.

“I came to know that invalid elders are given a final oil bath and forced to drink tender coconut juice, followed by tulsi juice and then milk (a customary predeath drink), with the relatives standing around chanting, `kasi', `kasi',“ Radhakrishnan says. But they are not the only devices employed. In some cases, hard pieces of murukku (a savoury) are forced down a resistant individ ual's throat, causing him or her to choke to death. Mud mixed with water is also used, with hopes that the watery Hemlock would cause indigestion -almost surely fatal to an already compromised body .

According to Dr N Raja, a geriatrician and private practitioner in Madurai, an oil bath followed by tender coconut juice, a coolant, results in the body's temperature falling to 94 or 92 degrees F from the normal of 98.4 degrees F. “It can also cause electrolyte imbalance, which can play havoc with the body's metabolism. And for a person who is already sick, it can even lead to cardiac arrest,“ he says.

Tirunelveli N Kannan, pro fessor of sociology , Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, says that this was an age-old practice which was not confined to any specific community. “I have heard people doing it in villages in Virudhunagar and also Usilampatti in Madurai, he says. “If closely researched we may see similar practices in many countries. “The issue of the person's consent in this practice, did not rise as in many cases he or she was terminally ill and almost unconscious. No person would willingly agree to being killed, but the community as a whole took the decision on his behalf, and went ahead with it,“ says Kannan. This was something that had social acceptance, he added.

S Alagarsamy , 78, says he has no fear of forced death. Although age has restricted his mobility , he believes he won't be a burden to his widowed daughter because of the free rations doled out by the state. “Mercifully the government provides us with free rice. Moreover, my daughter looks after me well, otherwise I would have feared the thalaikoothal, he says.

Radhakrishnan points out that death by thailakoothal is almost always signed off by a certifying doctor as death due to natural causes -old age in their case. “The truth will emerge if these deaths are better investigated,“ the NGO worker claims.

Incidentally , when Dr Raja discharges a patient in his care -one who may not have long to live -the patient's relatives sometimes ask him if they could perform the oil bath ritual. These people usually come from places like the rural pockets of Madurai, including villages in and around Usilampatti. “I tell them that it is illegal and that it should never be done, but I do not know if they follow my counsel.“

2016: Towards a law on euthanasia

The Hindu, February 2, 2016

Towards a law on euthanasia

The Union government has informed a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court that its experts are examining a draft Bill proposed by the Law Commission in its 241st report. However, it has been advised by the Law Ministry to hold back its enactment now, as the matter is pending before the court. Over a decade ago, the government felt that legislation on euthanasia would amount to doctors violating the Hippocratic Oath and that they should not yield to a patient’s “fleeting desire out of transient depression” to die. The government’s latest stand represents forward movement in the quest for a legislative framework to deal with the question whether patients who are terminally ill and possibly beyond the scope of medical revival can be allowed to die with dignity. The question was raised with a great deal of passion in the case of Aruna Shanbaug, a nurse who lay in a vegetative state in a Mumbai hospital between 1973 and 2015. In a landmark 2011 verdict that was notable for its progressive, humane and sensitive treatment of the complex interplay of individual dignity and social ethics, the Supreme Court laid down a broad legal framework. It ruled out any backing for active euthanasia, or the taking of a specific step such as injecting the patient with a lethal substance, to put an end to a patient’s suffering, as that would be clearly illegal. It allowed ‘passive euthanasia’, or the withdrawal of life support, subject to safeguards and fair procedure. It made it mandatory that every instance should get the approval of a High Court Bench, based on consultation with a panel of medical experts.

The question now before a Constitution Bench on a petition by the NGO Common Cause is whether the right to live with dignity under Article 21 includes the right to die with dignity, and whether it is time to allow ‘living wills’, or written authorisations containing instructions given by persons in a healthy state of mind to doctors that they need not be put on life-support systems or ventilators in the event of their going into a persistent vegetative state or state of terminal illness. The government’s reply shows that the Directorate-General of Health Services has proposed legislation based on the recommendations of an Experts’ Committee. The experts have not agreed to active euthanasia because of its potential for misuse and have proposed changes to a draft Bill suggested by the Law Commission. However, there seems to be no support for the idea of a ‘living will’, as the draft says any such document will be ‘void’ and not binding on any medical practitioner. It is logical that it should be so, as the law will be designed specifically to deal with patients not competent to decide for themselves because of their medical condition. This has to be tested against the argument that giving those likely to drift into terminal illness an advance opportunity to make an informed choice will help them avoid “cruel and unwanted treatment” to prolong their lifespan. To resolve this conflict between pain and death, the sooner that a comprehensive law on the subject is enacted, the better it will be for society.

2018: SC legalises passive euthanasia, living wills

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra & Amit Anand Choudhary, SC legalises passive euthanasia and living will, says right to life includes right to die, March 10, 2018: The Times of India

Lays Down Guidelines To Prevent Abuse

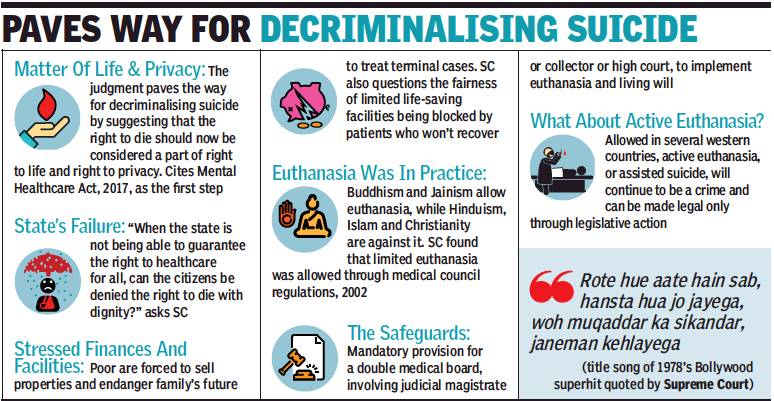

In a milestone verdict expanding the right to life to incorporate the right to die with dignity, the Supreme Court on Friday legalised passive euthanasia and approved ‘living will’ to provide terminally ill patients or those in a persistent and incurable vegetative state (PVS) a dignified exit by refusing medical treatment or life support.

The verdict, the latest in a string of boosts for individual freedoms by the SC, was delivered by a constitution bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices A K Sikri, A M Khanwilkar, D Y Chandrachud and Ashok Bhushan.

It empowers a person of sound mind and health to make a ‘living will’ specifying that in the event of him/her slipping into a terminal medical condition in future, his/her life should not be prolonged through a life support system. The person concerned can also authorise, through the will, any relative or friend to decide in consultation with medical experts when to pull the plug.

Given Indian sensitivities about life and death, testing the legality of the idea posed a complex medical, philosophical, constitutional and religious jigsaw for the bench.

CJI Misra led his colleagues on the bench to harmonise the inevitable yet opposite facets — life and death — and say in unison that “right to die with dignity is an intrinsic facet of right to life guaranteed under Article 21”.

With this ruling, the SC has recognised that an individual with terminal illness or in a state of irreversible vegetative condition has the agency to decide whether he/she would like to die, a sphere which was so far constitutionally reserved for the state, which alone could deprive a person of his/her life in accordance with law.

However, to prevent possible misuse by greedy relatives eyeing the patient’s property, the SC provided for stringent guidelines for preparing and giving effect to ‘living will’ and administration of ‘passive euthanasia’ by involving multiple medical boards comprising several experts and even judicial officers.

Only passive euthanasia will come under ambit of Article 21, says CJI

In a cumulative 538-page judgment containing four opinions, the SC said passive euthanasia, or a provision for passive euthanasia through ‘advance directive’ or ‘living will’, would save “a helpless person from uncalled for and unnecessary treatment when he is considered as merely a creature whose breath is felt or measured because of advanced medical technology”.

“There comes a phase in life when the spring of life is frozen, the rain of circulation becomes dry, the movement of body becomes motionless, the rainbow of life becomes colourless and the word ‘life’ which one calls a dance in space and time becomes still and blurred and the inevitable death comes near to hold it as an octopus gripping firmly with its tentacles so that the person ‘shall rise up never’,” CJI Misra said.

Writing the lead judgment with Justice Khanwilkar, CJI Misra said, “A dying man who is terminally ill or in PVS can make a choice of premature extinction of his life as being a facet of Article 21. We must make it clear that as a part of the right to die with dignity in a case of a dying man who is terminally ill or in PVS, only passive euthanasia would come within the ambit of Article 21 and not the one which would fall within the description of active euthanasia in which positive steps are taken either by the treating physician or some other person.”

Linking life and death with the thread of dignity, the SC said administration of life support system and medicines merely to prolong heart beat in a patient who was not even aware that he/she was breathing amounted to denial of dignity to that person who had no choice but to “suffer an avoidable protracted treatment”. The SC also ruled that a patient had the right to refuse medical treatment.

Justice Sikri adopted an unorthodox comparison of rights in his separate yet concurrent judgment and said, “Right to health is part of Article 21. At the same time, it is also a harsh reality that everybody is not able to enjoy that right because of poverty or other reasons. The state is not in a position to translate into reality this right to health for all citizens. Thus, when citizens are not guaranteed the right to health, can they be denied the right to die in dignity?” He also questioned the rationality of limited and costly life saving facilities getting occupied by rich patients in the ‘no return zone’ to deprive others who could be revived.

Justice Chandrachud opened yet another aspect of right to life by ruling on autonomy of an individual over his/ her body and ruled in his concurring judgment, “The state cannot compel an unwilling individual to receive medical treatment. While an individual cannot compel a medical professional to provide a particular treatment (this being in the realm of professional medical judgment), it is equally true that the individual cannot be compelled to undergo medical intervention.”

Justice Bhushan said, “An adult human being having mental capacity to take an informed decision has the right to refuse medical treatment including withdrawal from live saving devices.” CJI Misra and Justice Khanwilkar said, “His ‘being’ (existence) exclusively rests on the mercy of the technology which can prolong the condition for some period. The said prolongation is definitely not in his interest. On the contrary, it tantamounts to destruction of his dignity which is the core value of life. In our considered opinion, in such a situation, an individual’s interest has to be given priority over state interest.”