Musahar

Contents |

Musahar

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin according to Mr.Nesfield

Bhuiya Sada Banmanush, a Dravidian cultivating and servile caste of Behar, who appear to be an offshoot from the Bhuiya tribe of Chota Nagpur. 'rhe grounds for this opinion are stated at length in the article Bhuiya and need not be repeated here. The question of the origin of the caste has been examined by Mr. J. C. Nesfield in an elaborate monograph on The Mushem.s of Centml and Uppel' India, published ill the Calcutta Review for January 1888. Mr. Nesfield's inquiries into the traditions of the Musahars (as I prefer to spell the name) tend to connect them with the Cherus and Savars, who play a Prominent part in the legendary history of the Ganges valley. From this it would follow, if the stand8:rd classifica¬tion be accepted, that the Musahars belong to the Kolanan group of tribes, while my hypothesis would class them among the Dravidians. The distinction, however, between Kolarian and Dravidian appears to me, and, I believe, also to Mr. Nesfield, to rest solely upon peculiarities of language, which iu this case at any rate do not correspond to real differences of race. If the test of language is rejected, and we look only to physical characteristics, the so-called Dravidians and Kolarians can only be regarded as local varieties of one and the same stock. This being so, there is really no material difference between Mr. Nesfield's view and my own. He connects the Musahars of the North-Western Provinces with the Dravidian Savars and Cherus; I trace the Musahars of Behar to the equally Dravidian Bhuiyas of Southern Chota Nagpur. Both hypotheses may conceivably be correct. We both agree in thinking the Musa¬ hal'S a fragment of some Dravidian tribe recently and imperfectly absorbed into the Hindu caste system; and if this main point be conceded, it is not very important to determine from which of the known Dravidian tribes the fragment was broken off. The meaning and derivation of the name Musahar have often been discussed, and Mr. Nesfield has the following remarks on the subject :¬

"The name given to the tribe in this essay has been spelt throughout as Musbera, which is a slight departure from the spelling or spellings hitherto adopted in English books. The name has been supposed to be made up of two Hindi words signifying 'rat¬taker.' Hence in Buchanan's Eastem India they are described as a people' who have derived their name from eating rats.' But rat catching or rat-eating is by no means the peculiar, or even It prominent, characteristic of the tribe; and the name in Upper India at least is pronounced by the natives of the country as Mi1shera, and not as Musahar (rat-taker) or Miisarha (rat-killer). In an old folk-tale which` has recently come to my knowledge, the name is made to signify flesh-seeker or hunter, being derived from masu, 'flesh,' and he/'a, 'seeker,' and a legend is told as to the event which led to the tribe being driven to maintain itself by hunting wild animals. This is a more comprehensive title than rat-catcher, besides resting on better authority. Probably, however, both cultiva¬tions are fanciful, -Hindi versions of a name which is not of Hindi origin. It is certain that the more isolated members of the tribe, who still speak a language of their own unconnected with Hindi, call themselves by a name which sounds like Musbera; and it is not likely that men who have preserved their original speech con¬tinuously for so many centuries would have designated themselves by a name borrowed from a foreign language.

"There are one or two other names by which the tribe is known besides Musbera. In all the districts of Oudh in which the tribe is found, they are commonly, and in some places exclusively, known by the title of Banmanush, or man of the forest.

The name Banmanush is of purely Hindi origin; and though intended to be a term of reproach applied by Hindus to a people from whom they stand aloof as impure and savage, it has been accepted by Musheras themselves, many of whom scarcely know themselves by any other title, and all of whom are entirely ignorant of its origin and meaning. Other names, less commonly known or used, are Deosiyii, derived from their great ancestor Deosi; Bann'lj, or king of the forest, a less cont mptuous, or perhaps an ironical, form of the name Banmanush; and Maskhan, or eater of flesh, another form of the name MasellTa or Mushera. Sometimes, if a Mushera is asked to which of the great Indian castes he belongs, he will tell you that he is an Ahir, or rather a subdivision of Ahir, the caste of cowherd; and he appears to. be rather anxious to have his title to this honour recognized. But in point of fact he has no claim to any such lineage. Musheras are the hereditary enemies of Ahirs, as all their legends testify, and many are the petty raids that they have made against them for the possession of cattle and forest." I am myself inclined to believe that the popular etymology " rat-catcher" or rat-eater is the true one, and that the word is un opprobrious epithet bestowed by the Hindus on the caste with reference to their fondness for eating field-rats. :From Vedic times down to the present day we find the promiscuous habits of the non-Aryans in respect of food exciting the-special aversion of the Aryan colonists and forming the basis of depreciatory names which tend to sup¬plant the original tribal designation. It can hardly be expected that the givers of contemptuous names should be guided by a nice sense of scientific precision, and would stop to consider whether the practice of eating rats was really the peculiar or prominent characteristic of a particular tribe. The nickname would be bestowed atrandom, and it is conceivable that even in the same part of the country it might be conferred upon several different tribes.

Internal structure

The internal structure of the caste is shown in Appendix 1. So far as I can ascertain, the only sub• castes are Tirhutia and Maghaiya, and it is doubtful whether the distinction between these amounts to true endogamy or represents anything more than the fact that marriage between families living on opposite sides of the Ganges is comparatively Uncommon. The divisions Hikhmun and Balakmun appear now to be purely titular groups`, which bear no definite relation to marriage. It is a plausible conjecture that they were at one time exogamous sections, which broke up into smaller groups and thus lost their exogamons character. On the north of the Ganges the system of exogamy followed by the Tirhutia Musahars is very elaborate, and a man may not marry a woman belonging to his own section, or the sections o£ which his mother and his paternal and maternal grand¬mothers were members. If, again/ the excluded ascendants of a particular couple happened to be of the same section, the marriage is forbidden, although the boy and girl themselves belong to different sections. Among the more primitive Musahars further south the simpler rule prevails that a man may not marry a woman of his own section. This is the case also among the Bhuiyas; and there seem to be grounds for inspecting that the minute regulations which the Tirhutia Musahars affect to observe have been borrowed by them from some of their Hindu neighbours.

Marriage

On the north of the Ganges, Tirhutia Musahars are said to practise infant-marriage; while in Shahabad girls are usually not married until they have passed the age of puberty, and sexual intercourse before marriage is said to be tolerated. A bride-price of Rs. 2 is paid for a virgin, but the tender is reduced to half if there are reasons to doubt her integrity_ The marriage ceremony is based on the Hindu model, and does not differ materially from that in vogue among other low castes in Behar. The well-known formula- Ganga ka pani samundar ki sank Bar Kanya jag jag anand (May Ganges water and sea-shell betide Enduring bliss to bridegroom and to bride) is recited by one of the elders present, and water and rice are sprinkled on the bridegroom's head. The bride is then lifted by her mother, and the bridegroom marks her forehead five times with vermilion. Consummation follows at once, and the married couple usually leave for the bridegroom's house next day. Polygamy is said to be unknown. The remarriage of widows by the sagai form is permitted, and is not fettered by the common condition requiring the widow to marry her late husband's younger brother. Divorce is allowed, with the sanction of the caste pan¬ chayat, for infidelity on the part of the wife . . The husband breaks in two a piece of dried grass (kMw) in the presence of the panchayat, and formally renounces his wife by saying that in future he will look upon her as his mother. Divorced women may marry again by the ritual appointed in the case of widows.

Religion

The religion of the Musahars illustrates with remarkable clearness the gradual transformation of the fetichistic animism characteristic of the more primitive Dravidian tribes into the debased Hinduism practised in the lower ranks of the caste system. Among the standard gods of the Hindu Pantheon, Rali alone is admitted to the honour of regular worship. To her the men of the caste sacrifice a castrated goat, and the women offer five wheaten cakes with prayers that her favour may be shown to them in the pains of childbirth. In parts of Gya and Hazaribagh an earlier stage of her worship may be observed. Her shrine stands at the outskirts of the village, and she is regarded as a sort of local goddess, to be appeased on occasion, like the Thakurani Mai of the Hill Bhuiyas, by the sacrifice of a hog. It is curious to observe that the definite acceptance of Kali as a member of the Hindu system seems rather to have detracted from the respect in which she was held before she assumed this comparatively orthodox position. Her transformation into a Hindu goddess seems to have rendered her less mfllignant. Her worship, though ostensibly put forward as the leading feature of the M usahar religion, seems to be looked upon more as a tribute to social respectability than as a matter vitally affecting a man's personal welfare Kali, or Debi Mai, as she is I)ommonly called, may be appeased by an occasional sacrifice, but the Birs requirA to be kept constantly in good humour, or they may do serious mischief. The six Birs or heroes known as 'l'ulsi Bir, Hikmun, Ham Bir, Bhawar Bir, Asan Bir, and Charakh Bir are b€llieved to be the spuits of departed Musahars who exercise a highly malignant activity from the world of the dead. Rikmun is often spoken of as the plwka or ancestor of the caste, and when a separate sacrifice is offered to him the worshipper recites the names of his own immediate forefathers. On ordinary occasions the Birs are satisfied with offerings of sweetmeats prepared in ghi, but once in every two or thre9 years they demand a collective sacrifice of a more costly and eluborate character. A pig is provided, and country liquor, with a mixture of rice, molasses, and milk is offered at each of a number of balls of clay which are supposed to represent the Birs. 1 Then a number of Bhakats or devotees are chosen, one for each Bir, with the advice and assistance of a Brahman, who curiously enough is supposed to know the mind of each Bir as to the fitness of his minister. The shaft of a plough and a stout stake being fixed in the ground, crossed swords are attached to them, and the Bhakats having worked themselves up into a sort of hypnotic condition, go through a variety of acrobatic exercises on the upturned sword-blades. If they pass through this uninjured, it is understood that the Birs accept the sacrifice. The pig is then speared to death with a sharp bamboo stake, and its blood collected in a pot and mixed with country liquor. Some of this compound is poured forth on the ground and on the balls of clay, while the rest is drunk by the Bhakats. The ceremony concludes with a feat in which the worshippers partake of the offerings.

Priesthood

The Musahars have not yet attained to the dignity of keeping Brahmans of their own, though they call in Brahmans as experts to fix auspicious days for marriages and important religious ceremonies, to assist in naming children, and even to interpret the will of characteristic Musahal' deities like the Birs. In the matter of funeral ceremonies the tendency is to imitate Hindu usage. A meagre version of the standard sniddh is performed about ten days after death, and once a year, usually in the month of October, regular oblations are made for the benefit of deceased ancestors. It deserves notice that with Musahars, as with Doms, the sister's son of the deceased officiates as priest at the Sraddh .

Social status

The social status of the caste is pretty closely defined by the fact that they will eat any kind of food with all Hindu castes except Chamars, Dosadhs, Dhobi, Dom, and Mihtar, but Doms alone will take food from them. In matters of diet they have few soruples, eating pork, fowls, frogs, tortoises, alligators, jackals, cats, wild and tame snakes, snails, and various sorts of lizards. particularly the gosamp or ignana, while field-rats are esteemed a special delicacy. Beef and the flesh of 1 Some speak of the balls as the houses" of, the Birs, .but this ,seems to be a modem refinement on the primitive Idea, which recogzes no dlsinC-tion between the god himself and I•he fetish which represents him. horses and donkeys they hold to be forbidden. In the North-West Provinces, according to Mr. Nesfield, the Dolkarha or palanquin¬bearing Musahars eat horse flesh and keep fowls, while the Pahari and Dehati sub-tribes abstain from both, and regard the horse as a tabooed animal, whom it is sin for a Musahar to touch. The Paharis, however, eat beef when they can get it, and are only deterred from extensive cattle-lifting by their fear of the pugnacious grazier castes. Musahars are skilled, too, above other men in the knowledge of forest products, and use for food a number of roots, leaves, and fruits of which the ordinary Eindu knows nothing. They will not, however, cut or injure the km'ha1' tree, which is also held sacred by the Chamars.

Occupation

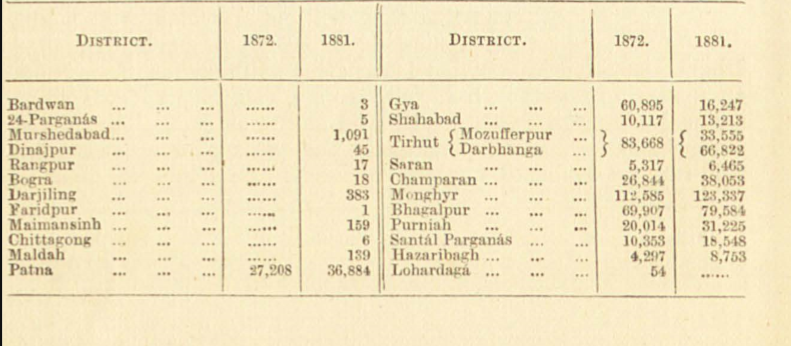

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Musahars in 18"12 and 1881 :¬

In Behar the bulk of the caste are field-labourers and palanquin¬bearers, and only a few have attained to the

dignity of oultivating on their own account, or have become possessed of occupancy rights. Further west the hill Musahars, described by Mr, Nesfield, "do not even know the us of the plough." but burn patches of forest and raise small crops in the ashes. Wherever the caste is found they strive to eke out the soanty yield of their agriculture labours by a variety of semi-savage pursuits, their heritage from more primitive modes of life. The rearing of ta aT silkworms, collecting stick-lac, resin and gum, making catechu, supplying Baidyas and Pansaris with indigenous drugs, stitching leaf plates and cutting wood for sale-all these may be reckoned among the characteristic occupations of the Musahar. We may add the watching of fields and crops by night, which Mr. N esfield shrewdly connects with the notion that the Banmanush, or "man of the forest" (a common designation of Musahars), is best able to propitiate the primeval deities whose ancient domain has been invaded by the plough. A.n interesting parallel may be found in colonel Dalton's statement that in Keonjhar, Bonai, and (lther Tributary States to the south the Bhuiyas, whom I hold to be the parent tribe from which the Musahars have sprung, "retain in their own hands the priestly duties of certain old shrines to the

exclusion of Brahmans." 1'he whole subject of the oocupations of the Musahars is discussed with the utmost thoroughness in Mr. Nesfield's admirable monograph.

See also

Musahar