Camels: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Laws

The Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015

The controversy in 2021

Deep Mukherjee, Nov 18, 2021: The Indian Express

For a long time now, camel herders and cattle rearers in Rajasthan have been carrying out a sustained opposition and protests against The Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015, citing loss of livelihood and business ever since the law was passed by the Rajasthan Assembly in 2015.

Over time, the controversial law has been raised in the state Assembly with the Rajasthan High Court also taking suo motu cognizance of the plight of camel herders after The Indian Express reported the issue in August. At the ongoing Pushkar cattle fair, the largest cattle fair involving camels in Rajasthan, people from the Raika and Raibari communities of camel herders have been vocal in their warning to the government that if the law is not amended, the camel population in Rajasthan could further fall.

What is the camel conservation law of Rajasthan?

The Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015, aims to provide for prohibition of slaughter of camels and also to regulate temporary migration or export thereof from Rajasthan.

According to the law, no person shall possess, sell or transport for sale or cause to be sold or transported camel meat or camel meat products in any form. It further adds that no person shall export and cause to be exported any camel himself or through his agent, servant or other person acting on his behalf from any place within the State to any place outside the State for the purposes of slaughter or with the knowledge that it may be or is likely to be slaughtered.

The law also regulates temporary migration of camels, saying that a ‘Competent Authority’ may issue special permit in the prescribed manner for their export from Rajasthan for agricultural or dairy farming purposes or for participation in an animal fair, and before granting such permission the Competent Authority shall also ensure that such export in no way reduces the number of such camels below the level of actual requirement of the local area.

This provision requires that for the migration of every camel outside Rajasthan for any purpose including legit sale, permission of the competent authority has to be required. As per the act, a competent authority means collector of a district and includes any other officer who may be authorised on this behalf by the state government by notification in the official gazette.

What were the reasons for the law being passed?

The then Vasundhara Raje-led BJP government has passed the camel conservation law citing that the animal is endangered and in need for initiation of sincere efforts for its conservation and protection.

“Several cases of intentional killings of camels and their progeny have come to light. It has also been observed that a large number of camels are transported or carried out of Rajasthan to other states for the purpose of slaughter. The recurrent famine and scarcity conditions in the State tend to increase this menace all the more. The existing laws are not sufficient to tackle this problem,” says the statements of objects and reasons for the 2015 law.

The then Rajasthan government had reasoned saying that the law was necessary after taking into consideration ‘the social, cultural and economic usefulness and contribution of camels.’ “Looking to the social, cultural and economic usefulness and contribution of camels, and to ensure their conservation, it is therefore, in general interest to enact a fresh law to prohibit the slaughter of camels as also to prohibit the export of such animals for the purposes of slaughter and to regulate, for other purposes, 26 the temporary migration or export of such animals in order to safeguard the camel species and also the interests of public deriving benefit from them,” the state government had said.

What has been its impact?

People from the Raika and Raibari communities, which have been rearing camels from generations, say that camel breeders say that the process of getting permission to transport camels outside the state as per the 2015 Act often takes months. This has resulted in a dip in purchasers from other states outside Rajasthan, who were earlier the primary customers who purchased camels from cattle fairs.

A look at the data of camels brought to the Pushkar cattle fair shows a substantial decrease than earlier. As per data from the Rajasthan Animal Husbandry department, in 2011, 8,238 camels were brought to the fair for sale but this figure went down to 3,298 camels in 2019.

Ever since the law was enacted, the difficulty in finding customers have resulted in a dire economic situation for camel herders, says camel conservation activist Hanwant Singh, director of Lokhit Pashupalak Sangsthan.

As a result, in the last few years, there have been sustained protests by camel rearers, with their worry being accelerated by the fact that the camel population in Rajasthan have been consistently decreasing.

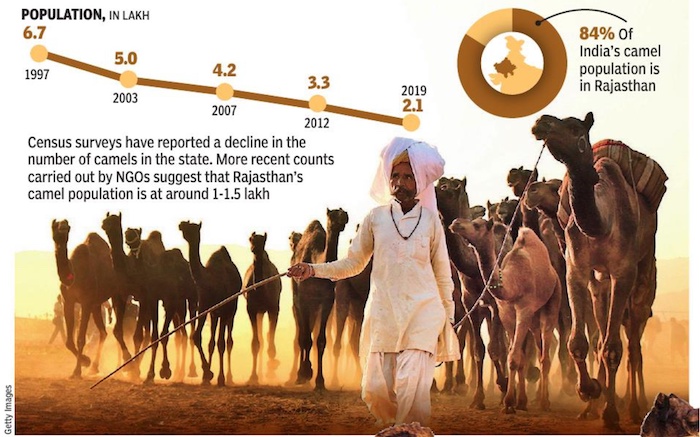

As per the provisional data of the 20th Livestock Census of Rajasthan, in 2019, there were 2.12 lakh camels in the state, which was much less than the figure in 2012, when there were 3.2 lakh camels in the state.

What is the incumbent Rajasthan government’s stand regarding the law?

In September this year, Rajasthan Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Minister Lalchand Kataria told the state Assembly that 84.43 per cent of total camels in the country are found in Rajasthan and their population has consistently decreased in the last 30 years.

The minister had said that in the next Assembly session, a government committee has decided that some amendments will be made to the 2015 Act to enable migration of camels and to ensure that farmers, who have stopped keeping camels after the law was passed, are encouraged to do so once again. The matter is also being monitored by the Rajasthan High Court, which had appointed advocate Prateek Kasliwal as amicus curiae to assist the court on the matter. In his report submitted to the High Court, Kasliwal calls for necessary amendments to the 2015 law, among other things.

Population

Rajasthan

1951-2019: declining numbers after 1992

2014-19: animals sold at the Pushkar fair

From: Nov 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Nov 7, 2019: The Times of India

See graphics:

1951-2019: Camel population in Rajasthan

2014-19: animals sold at the Pushkar fair

Camel population in Rajasthan, 1951- 2019

As in 2024

Intishab Ali, July 7, 2024: The Times of India

From: Intishab Ali, July 7, 2024: The Times of India

The camel is a dwindling tribe in Rajasthan. The numbers of this ship of the desert have been on the decline for quite some time in the desert state. The problem is that little seems to work to reverse the worrisome trend. Experts say it’ll take nothing less than a reimagining of the role and utility of the camel to help it prosper again. They’re gushing about milk, but everything from medicinal use to baby formula are part of the proposed solution to pull camels back from the brink.

In 2014, camel was declared the state animal of Rajasthan, which accounts for 84% of India’s camel population. Among other things, the move aimed at arresting its falling numbers restricted sales of the animal outside the state. That’s one of the chief factors now blamed for making its rearing economically unviable for camel herders. It’s said to have triggered distress sales of camels by Rajasthan’s indigenous Raika community, which is synonymous with camel-rearing.

Gradually, Raika youth have begun to switch from camel husbandry to regular jobs, seeing little promise in rearing camels. A series of camel censuses shows that the camel population in Rajasthan has fallen by over 50% since 2007. More recent surveys carried out by local NGOs suggest that Rajasthan’s camel population is now likely down to 1-1.5 lakh from over 6.5 lakh in the late 90s.

Sale Ban Hits Upkeep

“My grandfather had a herd of over 100 camels, but we have none now. Govt did not care for camels or their rehabilitation,” said 24-year-old Dhanna Ram, a resident of Kesar Desar Boran village in Bikaner district. Explaining the family’s reasons for shifting away from camels, Ram — he has enrolled in a B.Ed course in Bikaner — said they can’t sustain themselves “on rearing camels alone as they are no longer preferred modes of transport, and cannot be sold outside the state”.

Raikas are even struggling to feed their camels, said Motilal, a project coordinator at Urmul Seemant Samiti (USS), Bikaner. A USS survey of 3,500 camel herders in Bikaner, Jodhpur, Barmer, Jaisalmer, and Nagaur found that the camel population stands at about 1-1.25 lakh. “Grazing lands are simply not available anymore,” said Raghunath Raika of Bikaner. The problem, he said, deepened with the launch of the Indira Gandhi Canal project in Barmer, Bikaner, Churu, Hanumangarh, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, and Sri Ganganagar districts, for which several thousand acres of pasture lands were wiped out. A USS survey in 2019 to assess how camel owners maintained their herds found that rearing livestock rarely served as a steady source of livelihood.

“Those with one or two camels have been known to abandon them,” said USS project coordinator Suraj Singh, adding that stray camels can fall prey to accidents involving trains, etc. Hanwant Singh, director of Lokhit Pashupalak Sansthan (LPS), a Pali-based organisation that supports camel farmers, said that before it was made the state animal, a female camel would sell for a minimum of Rs 45,000. The result of the ban on sale outside the state was a drop in its price to as low as Rs 10,000.

Milk And Money

German-born veterinarian Ilse Kohler Rollefson, a recipient of the President’s Nari Shakti Award in 2016, and the German ‘Order of Merit’, says the ‘state animal’ status for camels is the root cause behind its decline.

“In principle, this was a well-intended move but its implementation was wrong since the prohibition on export of camels destroyed their economic value,” Kohler-Rollefson told TOI. “What Rajasthan needs is to change the law, legally protect camel-grazing areas, and build a value chain for camel products,” said Kohler-Rollefson, who set up Camel Charisma, a microdairy in Pali district. The veterinarian said popularising camel milk is one way to augment Raika incomes, but only if it is done “right”, which is through public-private partnership.

With its low-fat content and high medicinal value, camel milk is being pitched as nothing less than liquid gold. It is beneficial for treating diabetes and autism while camel blood, which is rich in immunoglobulins, is used in vaccine development.

In fact, the ICAR-led National Research Centre on Camel (NRCC) has collaborated with Rajasthan Cooperative Dairy Federation (RCDF) to buy camel milk from the Raika community. NRCC has also signed agreements with various research institutions to explore diverse applications for camel products.

Unlocking Medicinal Value

In Bikaner, NRCC and SP Medical College are jointly examining the potential benefits of camel milk for patients with tuberculosis and dengue. A study is under way at the Army School in Bikaner to assess the effects of camel milk on children with autism. Using camel milk for infant milk formula is also being explored as is its potential application in the treatment of cancer and diabetes. NRCC has signed an agreement with Bengaluru-based Indian Institute of Science to develop an improved anti-snake venom using camel serum. “Camel milk is a nutraceutical supplement. It can be called a pharmaceutical storehouse. It has medicinal properties and acts as natural insulin. It is useful against diabetes and autism. In a study of 108 autistic children in Pun- jab’s Faridkot, we found improvement in 30% of them. Children from different parts of the country with autism demand camel milk,” said Artabandhu Sahoo, Director, NRCC.

After a study among the Raikas showed zero prevalence of diabetes in the community, camel milk is now being promoted as a supplement to prevent the disease. NRCC has initiated steps to increase collection and sale of camel milk, which is also more affordable compared to cow and buffalo milk. While it currently retails at Rs 15 to Rs 20 per litre, experts say prices can be bumped up to Rs 60/litre if it’s sold as a health supplement.

RCDF has rolled out ‘Saras camel milk’ in Bikaner and is expected to start supplying to other cities in Rajasthan as well. LPS’s Hanwant Singh says it has been a long path to bringing camel milk to people. “In 1999, Rajasthan High Court ordered that camel milk was unfit for human consumption. We challenged the decision in Supreme Court and, in 2000, it ruled that camel milk is fit for human consumption. In 2016, it was also included in the Food Act. We started our own camel milk dairy and now collect 150-200 litres daily and supply to Hyderabad, Bangalore, Mumbai, Pune, and Jammu. Almost 90% of our product is targeted at children with autism,” he said.

Experts hope recent efforts to create awareness and encourage the Raika community to rear camels will ensure incremental improvements in the state’s camel numbers. With the next camel census due in 2025, they hope this ship stays afloat.

Camel slaughter

Ban can't be lifted: Madras HC

The Times of India, Sep 9, 2016

A Subramani

Camel slaughter ban can't be lifted, rules Madras HC

Camel slaughter banned in Tamil Nadu by the Madras high court order dated August 18 cannot be lifted, said the court on Friday rejecting a new public interest litigation that sought a direction to authorities to create slaughter facilities in the state. The court rejected the PIL a few days before the Muslim festival of Bakrid, during which camels are slaughtered in some places.

The court also directed the state government to ensure that its orders were not violated.

More significantly, the court made it clear that the jurisdictional police officers would be held responsible if camels were brought to their areas and slaughtered. Reiterating its prohibition order and pointing out that it was passed last month after hearing all stakeholders, the first bench of Chief Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Justice R Mahadevan said it could not entertain petitions that sought to circumvent its earlier orders. Earlier, counsel for Animal Welfare Board of India Jayesh Dolia referred to an article published in The Times of India on Friday about arrival of camels in north Chennai ahead of Bakrid, despite the court's ban.

When the already listed matter was taken up, the judges said they had banned camel slaughter not only due to the absence of slaughter facilities in the state, but also due to other factors such as transportation of the animals from far off places, including Rajasthan where shifting camels out of the state has been banned. The bench said camel is not native animal of Tamil Nadu, and added, "You cannot insist on sacrificing camel. Nobody prohibits sacrifice, but this animal is not in Tamil Nadu and it is not native to the state."

It also rejected the argument that camel slaughter came under essential religious practices. On August 18, the first bench had said: "In view of the stand of the central government and the provisions of the central Act, including Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, at present we cannot have a situation where such camel slaughtering is permitted, especially in the absence of any facility for it."