Champaran

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A contribution of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's struggle to bring succour to distressed peasants forced to cultivate indigo in Bihar's Champaran district happened exactly 100 years ago, but social scientists and researchers feel his methods remain relevant, even desirable, in today's fractured times.

The Champaran struggle is a very good example of a restrained moral struggle combined with social responsibility, says Salil Mishra, who teaches history at Dr B R Ambedkar University . “It shows how to mobilize opinion and support for a cause without resorting to moral hysteria,“ he says.

Sandeep Bhardwaj of Centre for Policy Research points out that there were no marches or strikes in Champaran. “Instead of defeating the opposition, Gandhi sought to win it over through the art of political persuasion. In contrast, the tendency in today's politics is often to burn down the house to light a candle achieve a political victory by any means necessary , even if it comes at the cost of larger communal harmony ,“ says Bhardwaj, who blogs at revisitingindia.com That's why , says social scientist Ashis Nandy , Gandhi's methods remain relevant. “There is an ethical component in his actions which has tremendous power and validity ,“ he says.

Indigo was an important crop for European planters in India. The conditions under which the peasants worked were oppressive. In his book, Gandhi in Champa ran, D G Tendulkar quotes a former magistrate of Faridpur, Mr E De-Latour of the Bengal Civil Service saying, “Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.“

Dinabandhu Mitra's play , Nil Darpan (1860), highlights the anguish of the peasant tenants (ryots).

“The story of Champaran begins in the early 19th century,“ writes Mridula Mukherjee in `India's struggle for Independence', “when European planters had involved the cultivators in agree ments that forced them to cultivate indigo on 320th of their holdings (known as the tinkathia system).“

The peasants had to pay enhanced rents over a period (sarahbeshi) or simply get out of the system paying a lump sum (tawan).

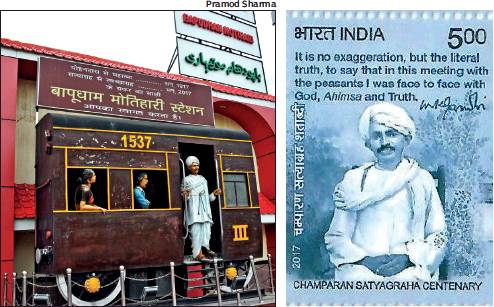

Gandhi arrived by train at Motihari in Bihar's Champaran district on April 15, 1917. He had come to the region following the request of Raj Kumar Shukla, a local cultivator. The next day, he was asked to leave.He refused, was taken into custody and summoned to court on April 18.

When Gandhi pleaded guilty, the colonial government was nonplussed. Unwilling to make him a martyr, authorities decided to withdraw the case and let him continue to gather statements of cultivators. On April 21, the case was withdrawn.

“Armed with evidence collected from 8,000 peasants, he had little difficulty in convincing the Commission that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and that the peasants should be compensated for the illegal enhancement of their dues,“ writes Mukherjee.

Misra points out that Champaran was the first systematic effort to introduce the peasant question into the nationalist politics.

“Till then the two had proceeded apart from each other.Nationalist politics was almost `peasant neutral' and peasant protests were local and spontaneous. Gandhi, who was an outsider to Champaran, introduced satyagraha and organised politics in the rural areas. He thus combined the rural with the national,“ he says.

“It was also at Champaran that Gandhi applied his techniques of satyagraha (perfected in South Africa) in India for the first time.Champaran should be seen as the first political laboratory in India where Gandhi made his experiments in satyagraha and then replicated them in other places (polite but firm defiance of the authority , basing struggles not simply on emotions and grievances but concrete enquiry and fact-finding, among others),“ he says.

And as Mahatma Gandhi himself wrote in his autobiography , “The Champaran struggle was a proof of the fact that disinterested service of the people in any sphere ultimately helps the country politically .“

Fighting To Keep Gandhi’s Memories Alive

Anam Ajmal , Sep 25, 2019: The Times of India

From: Anam Ajmal , Sep 25, 2019: The Times of India

How Champaran’s Indigo Kicked Off Gandhi’s Freedom Struggle

Bapu’s Karmabhoomi Fights To Keep His Memories Alive

Once a proud mansion, Belwa Kothi now wears the sadness of a ruin. The roof has surrendered to time, and the plaster is peeling. Close at hand lies a crumbling factory overrun by wild grass, forsaken like a stale idea.

But for this sleepy village in Bihar’s East Champaran district, these two buildings are reminders of its tryst with history. In the early 20th century, the factory was managed by a British officer AC Ammon and extracted neel (indigo), which farmers of the region were forced to cultivate on 15% of their land.

The oppressive system, known as tinkathia, was widely despised. Raj Kumar Shukla, a local farmer, drew Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s attention towards the exploitative system. Gandhi arrived in Bihar in April 1917, and Champaran became his first karmabhoomi in India. A worried Bettiah BDO wrote that Gandhi was “daily transfiguring the imaginations of masses of ignorant men with visions of an early millennium.” During those days of struggle, Gandhi had stayed for a night in Belwa.

While in Champaran, Gandhi shuffled between the district’s two main towns, Motihari and Bettiah. He travelled across the hinterland, recording statements of 8,000 cultivators. He convinced the Commission of Inquiry set up by the government that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and ensured that the planters refunded 25% of the amount they had taken illegally from farmers.

That was then. Now, Belwa lives on memories, and rues unfulfilled promises. Shukla’s grandson, Mani Bhushan Roy, who still lives in his grandfather’s ancestral village, is skeptical about what has been achieved post-Independence. “We have electric poles, but no electricity. And we have roads that flood during monsoons,” he says. He keeps Shukla’s red hard-bound pocket diary in a black polythene bag and opens it sometimes to remind government officials of the role his grandfather played in the freedom struggle.

To celebrate 100 years of that landmark moment in the national movement, busts of Gandhi and Kasturba were installed in Belwa by Bihar’s minister of rural development Shrawan Kumar in 2018. Just a few months later, Gandhi’s statue was beheaded by anonymous miscreants. “We have written to the administration several times after that, but no action has been taken to restore it,” a Belwa resident says.

Many places associated with the Champaran struggle are also gone. At the house of Gorakh Prasad in Motihari, Gandhi stayed and compiled farmers’ testimonies. The house, which served as Gandhi’s base, was razed to construct a new house.

The residence of another freedom fighter, Ram Babu Kedia, who hosted Gandhi on various occasions, has been converted into a school though the students remain unaware of its history. “We have heard our grandfathers say that Gandhiji stayed in this building. But these are private properties now, and the owners can use them as they see fit. These buildings could have been preserved only by the government, but no attention has been paid to them,” a teacher at Shikshayatan School said.

Yet, some are fighting to keep Gandhi’s spirit alive. For the past 20 years in Motihari, celebrations of the Mahatma’s life start a week before his birth anniversary. Tarkeshwar Prasad, who owns a general store, organises a “puja” on October 2. The whole town participates in the event, which starts with a prabhat pheri at 7am. Participants circle the town market first and then come to the pandal, where Gandhi’s statue is installed. “Gandhiji is like God for us. He did not just fight for independence; his fight was for the entire world because it showed everyone the importance of truth and non-violence,” says Prasad. Adds history enthusiast Bhairab Lal Das, who works as the project officer at Bihar Legislative Council, “The first chapter of the freedom movement started in Champaran. We need to restore places visited by Gandhiji to create public awareness and evoke a sense of pride.” Das has translated Shukla’s diary, which was written in Kaithi script, into Hindi. The homes where the leader visited might still be repaired but Gandhians lament that the Mahatma’s ideals are lost. Says Braj Kishore Singh, the 87-year-old secretary of the Gandhi museum in Motihari, “Today Gandhi survives, but only in museums and parks, on currency notes and in songs. His message of truth is no longer followed.”

Champaran and the making of the Mahatma

Just two years after he returned from South Africa...

Gandhi visited Champaran in April 1917 after learning of how cultivators there were being forced by British colonialists to grow indigo against their will under unfair terms

His opening shot was to hold a survey

Gandhi collected testimonies and statements of thousands of farmers on the atrocities and abuses inflicted on them by the British landlords And he armed people with knowledge, awareness of rights

During his stay in Champaran, Gandhi helped open three basic schools as he felt the people needed to be literate and learn about their rights. He also organised training in farming and other skills to promote self-reliance

In six months, Gandhi had made his point

Faced with the testimonies from Gandhi, an official Champaran inquiry committee was set up of which Gandhi himself was made a member. The committee submitted its report in October 1917 with recommendations that favoured the peasants. Finally, coercive indigo cultivation ended with the passage of a law in March 1918