Cheetahs: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Extinct in India

Cheetah sprinting towards extinction, AGENCIES, Dec 28 2016 : The Times of India

India was home to many cheetahs back in the day, but the last is believed to have been killed in 1947.The cheetah was declared extinct in India in 1952 -the only large mammal to have been declared extinct in the country, according to the Union environment ministry.

Zoological Society of London said in a statement, “The cheetah is sprinting towards the edge of extinction and could soon be lost forever un less urgent, landscape-wide conservation action is taken.“

There were an estimated 100,000 cheetahs (in the world) at the beginning of the 20th century, according to previous estimates.

“Given the secretive nature of this elusive cat, it has been difficult to gather hard information on the species, leading to its plight being overlooked,“ said Sarah Du rant, the report's lead author and project leader for the Rangewide Conservation Programme for Cheetah and African Wild Dog. “Our findings show that the large space requirements for cheetah, coupled with the complex range of threats faced by the species in the wild, meant that it is likely to be much more vulnerable to extinction than was previously thought,“ she said. Cheetahs travel widely in search of prey with some home ranges estimated at up to 3,000 square kilometres.

The study found that 77% of the animal's remaining habitat falls outside protected areas, leaving it especially vulnerable to human interference. The main risks are humans hunting their prey , habitat loss, illegal trafficking of cheetah parts, and the exotic pet trade, according to the study . Durant hailed recent commitments taken by the international community , including on stemming the flow of live cats from the Horn of Africa region. “We've just hit the reset button in our understanding of how close cheetahs are to extinction,“ said Kim Young-Overton, from the wild cat conservation organisation Panthera.

Introduction in India

Complexities

Ravi Chellam, March 21, 2022: The Hindu

From: Ravi Chellam, March 21, 2022: The Hindu

THE GIST

Historically, Asiatic cheetahs had a very wide distribution in India. There are authentic reports of their occurrence from as far north as Punjab to the Tirunelveli district in Tamil Nadu. The cheetah’s habitat was also diverse, favouring the more open habitats: scrub forests, dry grasslands, savannas and other arid and semi-arid open habitats.

The consistent and widespread capture of cheetahs from the wild over centuries, its reduced levels of genetic heterogeneity due to a historical genetic bottleneck resulting in reduced fecundity and high infant mortality in the wild, its inability to breed in captivity, ‘sport’ hunting and bounty killings are the major reasons for the extinction of the Asiatic cheetah in India.

The main goals of the cheetah Action plan is to make cheetahs perform its functional role as a top predator and to use the cheetah to restore open forest and savanna systems. Both of which are already being done by extant species like the Asiatic lion and the leopard.

The story so far: The cheetah, which became extinct in India after Independence, is all set to return with the Union Government launching an action plan. According to the plan, about 50 of these big cats will be introduced in the next five years, from the Africa savannas, home to cheetahs, an endangered species.

What was the distribution of cheetahs in India? What were the habitats?

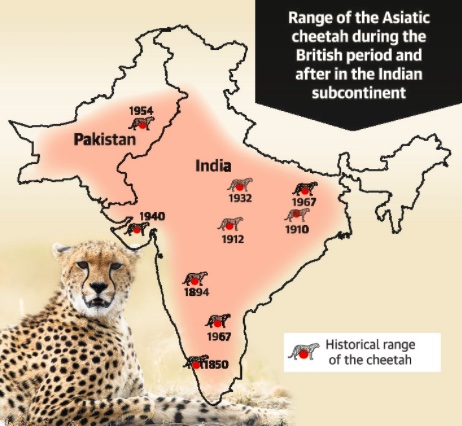

Historically, Asiatic cheetahs had a very wide distribution in India. There are authentic reports of their occurrence from as far north as Punjab to Tirunelveli district in southern Tamil Nadu, from Gujarat and Rajasthan in the west to Bengal in the east. Most of the records are from a belt extending from Gujarat passing through Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha. There is also a cluster of reports from southern Maharashtra extending to parts of Karnataka, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The distribution range of the cheetah was wide and spread all over the subcontinent. They occurred in substantial numbers. The cheetah’s habitat was also diverse, favouring the more open habitats: scrub forests, dry grasslands, savannas and other arid and semi-arid open habitats. Some of the last reports of cheetahs in India prior to their local extinction are from edge habitats of sal forests in east-central India, not necessarily their preferred habitat.

In Iran, the last surviving population of wild Asiatic cheetahs are found in hilly terrain, foothills and rocky valleys within a desert ecosystem, spread across seven provinces of Yazd, Semnan, Esfahan, North Khorasan, South Khorasan, Khorasan Razavi and Kerman. The current estimate of the population of wild Asiatic cheetahs is about 40 with 12 identified adult animals. They occur in very low density spread over vast areas extending to thousands of square kilometres.

What caused the extinction of cheetahs in India? When did they disappear?

The cheetah in India has been recorded in history from before the Common Era. It was taken from the wild for coursing blackbuck for centuries, which is a major contributor to the depletion of its numbers through the ages. Records of cheetahs being captured go back to 1550s. From the 16th century onwards, detailed accounts of its interaction with human beings are available as it was recorded by the Mughals and other kingdoms in the Deccan. However, the final phase of its extinction coincided with British colonial rule. The British added to the woes of the species by declaring a bounty for killing it in 1871.

The consistent and widespread capture of cheetahs from the wild (both male and female) over centuries, its reduced levels of genetic heterogeneity due to a historical genetic bottleneck resulting in reduced fecundity and high infant mortality in the wild, its inability to breed in captivity, ‘sport’ hunting and finally the bounty killings are the major reasons for the extinction of the Asiatic cheetah in India.

It is reported that the Mughal Emperor Akbar had kept 1,000 cheetahs in his menagerie and collected as many as 9,000 cats during his half century reign from 1556 to 1605. As late as 1799, Tipu Sultan of Mysore is reported to have had 16 cheetahs as part of his menagerie.

The cheetah numbers were fast depleting by the end of the 18th century even though their prey base and habitat survived till much later. It is recorded that the last cheetahs were shot in India in 1947, but there are credible reports of sightings of the cat till about 1967.

What are the conservation objectives of introducing African cheetahs in India? Is it a priority for India? Is it cost effective?

Based on the available evidence it is difficult to conclude that the decision to introduce the African cheetah in India is based on science. Science is being used as a legitimising tool for what seems to be a politically influenced conservation goal. This also in turn sidelines conservation priorities, an order of the Supreme Court, socio-economic constraints and academic rigour. The issue calls for an open and informed debate. Eminent biologist and administrator T.N. Khoshoo, first secretary of the Department of Environment, spoke out strongly against the cheetah project in 1995. “The reintroduction project was discussed threadbare during Indira Gandhi's tenure and found to be an exercise in futility,” he said, pointing out that it was more important to conserve species that were still extant such as the lion and tiger, rather than trying to re-establish an extinct species that had little chance of surviving in a greatly transformed country.

Mr. Khoshoo’s views are in sync with the 2013 order of the Supreme Court which quashed plans to introduce African cheetahs in India and more specifically at Kuno national park in Madhya Pradesh.

The officially stated goal is: Establish viable cheetah metapopulation in India that allows the cheetah to perform its functional role as a top predator and to provide space for the expansion of the cheetah within its historical range thereby contributing to its global conservation efforts.

African cheetahs are not required to perform the role of the top predator in these habitats when the site (Kuno) that they have identified already has a resident population of leopards, transient tigers and is also the site for the translocation of Asiatic lions as ordered by the Supreme Court of India in 2013. In other open dry habitats in India there are species performing this role, e.g., wolf and caracal, both of which are highly endangered and need urgent conservation attention. Even the Government’s official estimate is expecting, at best only a few dozen cheetahs at a couple of sites (that too only after 15 years) which will require continuous and intensive management. Such a small number of cats at very few sites cannot meet the stated goal of performing its ecological function at any significant scale to have real on ground impact. Clearly, there are far more cost-effective, efficient, speedier and more inclusive ways to conserve grasslands and other open ecosystems of India.

Apart from establishing a cheetah population in India, the stated objectives include: To use the cheetah as a charismatic flagship and umbrella species to garner resources for restoring open forest and savanna systems that will benefit biodiversity and ecosystem services from these ecosystems.

Asiatic lions and a variety of species already found in these ecosystems can very well perform this role and more. If the government is serious about restoration and protection of these habitats, it first needs to remove grasslands from the category of wastelands and prevent further degradation, fragmentation and destruction of these habitats. Investing directly in science-based restoration and inclusive protection of these ecosystems will yield results much more quickly and sustainably than the introduction of African cheetahs.

Another goal is to enhance India’s capacity to sequester carbon through ecosystem restoration activities in cheetah conservation areas and thereby contribute towards the global climate change mitigation goals. Experts contend that this objective does not require the introduction of African cheetahs, at a cost of ₹40 crore, with the attendant risks of diseases which haven’t really been dealt with.

What is the current status of this project? What are the chances of it succeeding?

According to the Government, Kuno is ready to receive the cheetahs. About a month ago a team of government officials visited Namibia to inspect the cheetahs that would be sent to India, review the arrangements and to reach an agreement for the transfer of the cats. It is being reported that Namibia wants India’s support for lifting the CITES ban on commercial trade of wildlife products, including ivory. The draft memorandum of understanding shared by Namibia reportedly contains a condition requiring India to support Namibia for “sustainable utilisation of wildlife”. Negotiations are currently underway to finalise the MoU and it is expected to be signed by the end of March. The cheetahs are to be provided by the Cheetah Conservation Fund, an NGO, and not the Namibian government. Three to five cheetahs are expected to be part of the first group of cats and these are expected to arrive as early as May 2022 and released in the wild by August 15.

Given all the challenges, especially the lack of extensive areas extending in hundreds if not thousands of square kilometres with sufficient density of suitable prey, it is very unlikely that African cheetahs would ever establish themselves in India as a truly wild and self-perpetuating population. A likely unfortunate consequence of this initiative will be the diversion of scarce conservation resources, distraction from the real conservation priorities and a further delay in the translocation of lions to Kuno.

Ravi Chellam is CEO, Metastring Foundation, and member, Biodiversity Collaborative

2020: SC nod for cheetah’s return to the wild

Dhananjay Mahapatra, January 29, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: You need not travel all the way to Africa to see the elegant cheetah in the wild. The fastest land animal may soon roam our jungles, initially in MP’s Kuno Palpur sanctuary, more than 70 years after it was hunted to extinction by the maharajas and the British.

For a decade, the National Tiger Conservation Authority has been knocking on the Supreme Court’s door for introduction of cheetah into the sanctuary, saying this was an ideal habitat for the animals to be brought from Namibia. But the SC in 2013 had refused to introduce a “foreign species” without a study on its impact on fauna. On Tuesday, it gave its nod to cheetah’s introduction “on an experimental basis” after carefully choosing the habitat and monitoring to see if it can adapt to Indian forests.

Last cheetahs were hunted down in 1947

Noted environment conservationist M K Ranjitsinh argued for introduction of cheetah from Africa. “This is the only species the Indian jungles have lost though we have managed to maintain a healthy number of other endangered species. It can be introduced in India after studying suitability of habitat,” he said. The last of the cheetahs are said to have been hunted down in 1947 by the maharaja of Sarguja, now in Madhya Pradesh.

A bench of Chief Justice S A Bobde and Justices B R Gavai and Surya Kant said it was not a re-introduction but an introduction of African cheetah to the Indian jungle. Praising Ranjitsinh’s work in wildlife conservation, especially in raising the numbers of Great Indian Bustard in Rajasthan, it said, “Cheetah will be introduced on an experimental basis after carefully choosing the habitat, nurtured and watched to see whether it can adapt to Indian jungles.” The NTCA had zeroed in on Kuno Palpur sanctuary for introduction of cheetah.

The bench said, “If the experiment is successful, then the NTCA, guided by the committee, will take a nuanced decision about viability of introducing cheetah in large scale. This committee shall submit a report to the court every four months.”

Restoration of the cheetah population

2022

P Naveen, Sep 18, 2022: The Times of India

From: P Naveen, Sep 18, 2022: The Times of India

SHEOPUR (KUNO): Seven decades after the last cheetah was hunted to extinction in India, its cousins from Africa are here to take their spot in the Indian sun.

At 11.30 am on Saturday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi operated a lever to open a gate and release eight cheetahs into a special enclosure. He captured the moment on a camera as the cheetahs scampered about, checking out their new home. Jet-lagged after a 9,000-km overnight flight from Namibia to Gwalior, and then to the Kuno helipad, the cheetahs looked at their new surroundings a bit tentatively at first, but were soon sprinting about.

The release of the sleek predators was planned to coincide with PM Modi’s birthday — he turned 72 on Saturday — with Madhya Pradesh chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan and several Union ministers present on the platform for the unique event.

“Decades ago, the age-old link of biodiversity was broken and became extinct, today we have a chance to restore it,” PM Modi said, adding: “Today, the cheetah has returned to the soil of India.”

It’s very rare for a species extinct in one part of the world to be replaced by a lot from another, especially an apex predator. The whole world had its eyes on the world’s first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project, a mission that took decades to dream and years to plan and work out.

See also

A search for ‘cheetah’ through the Search box (top right) will yield links to Cheetahs in the Indian tradition.