Chettinad Houses

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Chettinad Houses: Tamil Nadu

The Times of India, Aug 28, 2011

Padmini Sivarajah

Huge houses that are more than 75 years old line the streets of the 96 villages around Karaikudi in Sivaganga district in southern Tamil Nadu. Most of the mansions, though, are locked up as their owners are far away in Delhi, Singapore, the US and beyond. One such absentee owner is Union home minister P Chidambaram, a Chettiar who owns a share in a huge old Chettinad house that was recently broken into — something that the local police say is not uncommon among ancient houses in the region.

“Anyone can gain access to the homes if they are not guarded because the streets are deserted most of the time,” says a senior police officer. “Some houses might have lost valuables but the owners may not even be aware of the theft due to the sheer size of these structures.”

Most Chettinad houses are an opulent blend of 19th century grandeur and 21st century practicality. Polished planter’s chairs sit on Italian marble next to bright orange sofas that date to just a decade ago. Palm leaf baskets are stacked up next to plastic lunch bags, and ancient brass water filters and idli steamers stand in a corner opposite spanking new gas stoves.

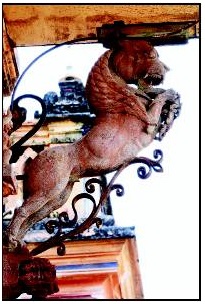

“Chettinad houses are known for their unique architecture that ensures open space, sunlight and ventilation,” says A Chandramouli, who has turned his 100-year-old 40,000 square foot house into a heritage hotel. Intricately carved pillars of teak, granite, marble and iron that add grandeur to these houses stand testimony to the wealth of each family.

The Raja Palace, which belongs to Ramasamy Chettiar and was built in 1902, is the most imposing of the houses with pillars made from a single piece of wood standing more than 10 feet tall. Chinnasamy, a resident of Athangudi village, says his father told him that moneyed Chettiars filled the hollow columns of the wood and granite pillars with valuable gems in the last century.

The story of Chettinad, or the country of the Chettiars — as Karaikudi is also known — began when the Nattukottai Chettiars migrated from Cauvery Poompattinam in the 13th century following a flood. The Chettiars, traditionally a banking and business community, crossed the seas to the south and south-east Asia, particularly Burma and Ceylon, to trade. They brought back money, gold, teak and jewellery from Burma, and tiles, glass and marble from Italy to build fabulous homes in their native villages.

Sunlight still streams into the courtyards and open spaces, reflecting off the polished floors and burnished teak columns. “The houses were designed so that there is enough sunlight, and the airflow keeps the house cool throughout the year. The inner walls of the house do not have direct contact with sunlight,” says Chandramouli.

The walls are plastered with a mixture of eggshells, egg yolks and gallnuts. Another striking feature of these houses is the rainwater harvesting systems. Water running down the tiled roof falls onto the black stone floor in the courtyard and is collected in huge brass pots, which are closed with heavy lids.

There are garages for cars, stables with the remains of horse and bullock carts in the backyard, and rooms for the huge domestic staff that needed to run the gargantuan homesteads. Drains run beneath the floors of the houses to ensure the rainwater collected in the central courtyards peters out. Beautiful carvings of lion heads or peacocks mark the external openings of the drains.

Murugan, who guards one of the smaller mansions adjoining the Raja Palace in Kanadukathan, says maids would mop the floors with water and coconut oil every day to maintain the sheen of the Italian marble and the traditional ‘Athangudi’ tiles that are unique to the region. The palace, which is usually open to the public and where some Tamil films have been shot, has been under renovation for the past year.

All the houses have two levels; this ensures residents can retire to safety in case of floods, a natural phenomenon they are still afraid of as they believe the sea destroyed their native place of Cauvery Poompattinam.

K P Bharathy, project officer of the tourism wing of Dhan Foundation, who is interested in Chettiar architecture, said the Chettiars brought back styles of art and architecture that they saw during their travels across the world. “The doors have intricate wood work based on Hindu mythology. Today, they are worth lakhs of rupees,” he says. “You will see Kerala woodwork, Italian frescos, Victorian and Anglo-Indian art, intricately carved iron grills, Gothic domes and arches in these buildings. But they come together beautifully.”