Culture and Government patronage: Pakistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Culture and Government patronage: Pakistan

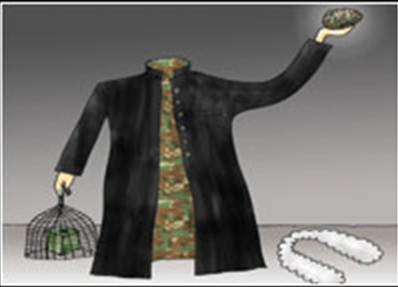

The good monster

By Nadeem F. Paracha

A leader’s true legacy tends to be more accurately deciphered when studied through the effects his ideas and policies have had on the cultural mindset of the people. When the late Zulfikar Ali Bhutto took over the reins of power in 1972, he presided over a country disillusioned by the defeat of the Pakistan Army in the former East Pakistan. Society stood quivering from a collective case of low self-esteem and widespread melancholy.

Thus, one of the Bhutto regime’s most important contributions to Pakistan were its cultural policies that helped revive the people’s dwindling esteem and energy, eventually giving them a new-found self-belief. Inventively borrowing bits of cultural ideas from various socialist regimes of the time, especially from Mao’s China, the Bhutto regime used commercial cinema, state-owned media and government-funded folk melas to hit home slogans and concepts that were conceived to help construct a new Pakistani mindset.

Though Bhutto’s political legacy is controversial, his regime’s cultural legacy is ripe with glowing examples of great leaps made in various forms of art, enough to (for the first time in Pakistan) culturally engage the common man and oversee a great revival of his spirit. But heroic politics can be viciously ironic too. As a stressful global economic meltdown brought on by the oil crisis of the 1970s had an impact on Pakistans economy, it also left the country’s elite and middle-classes pointing an accusing finger at Bhutto’s populist economic policies. Soon, the new-found political and cultural consciousness inspired by the Bhutto regime made an ironic u-turn to play a decisive role in its designer’s tragic downfall.

Using the slogan of ‘Nizam-i-Mustafa’, the opposition successfully used the new-found consciousness of the masses to turn it against its own architect. After Bhutto’s toppling, the country’s cultural scene lay barren like a wasteland of moral myopia for eleven years under the infamous Zia dictatorship. 1999 saw Pervez Musharraf assume the role of the country’s new dictator, overseeing a country not only suffering from severe political factionalism and economic disarray, but still carrying the agony of the inertia-laden Ziaist mindset that seemed to have got worse during the country’s “decade of democracy” in the 1990s.

Perhaps due to being busy playing politics of bare survivalism, Benazir and Nawaz Sharif both had little time to invest in the sort of cultural policies that actually affect mindsets. To his credit, Musharraf aggressively addressed the deepening trend of negative conservatism that had gripped the Pakistani frame of mind, putting an impressive amount of personal effort to revive Pakistan’s evaporating cultural polity.

Just as Z.A. Bhutto’s cultural policies had managed to attract widespread engagement from the masses, only for this new consciousness to ironically play itself into the hands of those wanting to pull Bhutto down, Musharraf today is faced with a similar quandary

In an environment in which the reactionary mindset had hit a peak, Musharraf led the charge in giving state patronage to various modern art forms, going a step further by adding to his agenda the proliferation of private TV channels allowed to interpret politics, society and entertainment on their own terms. Like the Z.A. Bhutto regime, the Musharraf regime’s cultural policies too were closely intertwined with his politics, managing to have an altering impact on the mindset of the country.

Thanks to the patronage given by the Musharraf regime to mostly youth-oriented art forms and activities, and owing to the relationship that developed between this and the open media policies of the government, cultural policies of the regime eventually gave birth to an interesting phenomenon. However, just as Z.A. Bhutto’s cultural policies had managed to attract widespread engagement from the masses, only for this new consciousness to ironically play itself into the hands of those wanting to pull Bhutto down, Musharraf today is faced with a similar quandary.

Though Musharraf’s cultural strategy may not have engaged the common man the way Bhutto’s policies did, however, it did have a deep impact on urban, middle-class Pakistan. This happened in two stages. The first was the proliferation of a new-found sense of creative freedom among the urban middle-class youth, and the next stage was when this astute sense eventually evolved into a political awakening of sorts.

As one section of the middle-class youth responded with newborn religiosity, the other part blossomed in their new-found freedom, with gradual economic growth witnessed by the economy making the experience that much sweeter. Then arrived the political awakening. Very much an evolutionary outcome of Musharraf’s positive cultural and economic policies, this outcome, however, released its political energy against the very man that had initiated it as a cultural initiative.

But this ironic phenomenon is not as damaging to its architect’s well being as were the paradoxical consequences of Bhutto’s cultural regime. On the contrary, it is likely that in the long run, this phenomenon will see young people now grow up to look for social, economic and political solutions in concepts like democracy, freedom of speech and a more secular form of politics rather than, unlike their predecessors, turn inwards in times of crisis by clinging to military dictators, obscurantism, myopic morality and political inertia.

It is a fascinating irony, and a realisation that such a hopeful thought about the future has been triggered by cultural initiatives of a man who ruled Pakistan as a military dictator. However, today, as the lawyers, the media and sections of the youth get busy exercising their new-found political energies in shouting him down, Musharraf will have to wait for history to finally deliver its verdict, which will likely read as follows: A military dictator’s cultural impositions actually gave birth to a newborn sense of democracy. Weird, but true.