Dosadh

Contents |

Dosadh

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Tradition of origin

A degraded Aryan or refined Dravidian cultivating caste of Behar and Chota Nagpur, the members Of which are largely employed as Village watchmen and messengers, and bear a very evil reputation as habitual criminals. Dosadhs claim to be descended from the soldiers of the Pandava prince Bhima or Bhim Sen, and to be allied to the Oheros, who are supposed at one time to have ruled in Behar. Buchanan thought there was "some reason to suspect" that the Dosadhs might be the same tribe as the Ohandals of Bengal, basing this conjecture on the statement that "the two castes follow nearly the same professions and bear the same rank, while the Ohandals pretend to be descended of Rahu, and, I am told, worship that monster." In fact, however, the Ohandals do not worship Rahu or trace their origin to him, and the Dosadhs revere a host of deified heroes, a form of worship entirely unknown to the OhandaL 'fhe young men of the caste are often rather good-looking, and many of them have a yellowish brown oomplexion with wide, expanded nostrils and the tip of the nose slightly turned up. The complexion, however, and the shape of the nose show a range or variations which seems to indicate considerable mixture of blood.

Professor M antegazza, following Dalton, describes them as " Aryans of a very low type;" and it seems about equally likely that the original stook may have been a branch of the Aryans degraded and coarsened by crossing with lower races, or a non-Aryan tribe refined in feature aud raised in stature by intermixture with semi-Aryan castes. In Northern Behar there bas probably been some infusion of Mongolian blood; and in all parts of the country some allowance must be made for the fact that members of any Hindu caste except the Dom, Dhobi, and Ohamar may gain admission into the Dosadh community by giving a feast to the heads of the caste and eating pork and drinking liquor in token of their adoption of Dosadh usage. This privilege, no doubt, is not eagerly sought for, and most of those who join themselves to the Dosadhs after this fashion have probably got into trouble with their own people for keeping a Dosadh mistress or doing something disreputable. Still the existence of a regu1ar procedure for enrolling recruits from other castes shows that such cases are not unknown, and they must tend in some measure to modify the physical type of the caste.

Internal structurs

The caste is divided into eight sub-castes :-Kanaujia, Magahiya, Bhojpuria, Pailwar, Kamar or Kanwar, Kuri or Kurin, Dharhi Dhar, Silhotia or Sirotici, Bahalia. The members of nearly all these groups will eat cooked food together, but do not intermarry. The Dharhi, however, who pretend to be descended from a Goala who accidentally killed ft cow, and disclaim all connexion with the Dosadhs, are excluded from this privilege; and the Kamar have only recently cleared themselves from the suspicion of eating beef and been admitted to social intercourse with the other sub-castes. Ooncerning the Bahalia there is some question whether they are Dosadhs at all, and it has been maintained that they are a distinct caste of gypsy¬like habits, and possibly akin to the Bediyas. . Most Bahalias, however, insist on theil' title to be considered Dosadhs, and in Bengal at any rate the Bahalia and Dosadh eat and smoke together, and, though they do not intermarry, behave generally as if they were branches of the same stock. r1'he sections (dilt, m~tl, pariah, or pangat), which are very numerous, are shown in Appendix 1. In app1ying the rule of exogamy to a particular case the caste profess to exclude the sections of (1) the father, (2) the paternal grandmother,

(3) the paternal great-grand-mothers, (4) the paternal great-great-grandmothers, (5) the mother, (6) the maternal grandmother, (7) the maternal great-grandmothers, and to follow the double method of reckoning explained in the article on Bais. So that if the proposed bridegroom's maternal grandmother should happen to have belonged to the same section as one of the proposed bride's paternal great¬great-grandmothers, the marriage would be disallowed notwithstand¬ing that the parties themselves belong to different sections. It is obvious, however, that entire conformity with so complicated and fa\,-reaching a scheme of prohibitions req uires tb at genealogies shall be careIullykept up and infringements of the rules jealously watched for by the headmen and pancM-yats, who in the first instance determine the question whether a particular couple may marry or not. rrhere are indeed officials called pan:iiars or genealogists, who are supposed to act as referees in such matters, but the caste as a whole is on a very low educational level, and it is very doubtful whother the strict letter of these rules is invariably complied with. It will be seen that nearly all the sections of the Magahiya and Pailwar sub-castes are titular, while most of the other sub-castes have local or territorial sections. The Bahalia have no sections, and regulate their marriages by the standard formula for reckoning pro¬hibited degrees calculated to seven generations in the descending line. 'rhis formula is also used by the other sub-castes as supple¬mentary to their system of exogamy.

Marriage

Dosadhs marry their daughters whenever they can afford to do so, but they do not hold the strict view of the spiritual necessity of infant-marriage which is current among the higher castes, and the fact of a girl's marriage being deferred until she has passed tlle age of puberty is not deemed to put any special slur on the family to which she belongs. Some Dosadhs, however, hold that an adult bride is not entitled to the full marriage service (biya/t), but must be married by the sag{tt form used at the remarriage of a widow. 'l'he marriage ceremony is a somewbat meagre copy of the ritual in vogue among midclle¬class Hindus. "\Vell-to-do Dosadhs employ Brahmans to officiate as priests j but this practice is not general, and most members of the caste content themselves with getting a BrahmAn to fix au auspicious day for the event, and to mutter certain formulro (mantras) over the vermilion, the smearing of which on the bride's forehead constitutes the binding portion of the rite. An infant bride is kept in her parent's house until she reaches puberty, at the age of twelve or fourteen, when the gauna ceremony is performed, her nails are cut and stained red, and her husband takes her to his own house. Consum¬mation does not take place until after the gauna ceremony. Polygamy is permitted to a limited extent.

A man may in no case have more than two wives, and he is Dot supposed to take a second wife at all unless the first is childless or suffers from an incurable disease. In the Santal Parganas, however, three wives are allowed, and the tendency is to follow the aboriginal usage of unlimited polygamy. A widow may marry again by the sagai form, and it is deemed right. on grounds of domestic convenience, for her to marry her late husband's younger brother if such a relative survives him. In the event of her marrying an outsider she takes no share iu her late husband's property, and any obildren she may have had by him remain in the charge of his family. Divorce is permitted by all sub•castes except the Kamal', with the sanction of the panchayat, for adultery and persistent disobedience or ill-temper on the part of the wife. In the San tal Parganas and Palamau a sal leaf is torn in two or a stick broken to symbolise the separation of the couple. DivorcE'd women may marry again by the sagai rite, but they must first give a feasi to the members of the caste by way of atonement £01' their previous misconduct.

Religion

Most Dosadhs, if questioned about their Religion, will persistently aver that they are orthodox Hindus, and inproof of this allegation will refer to the fact that they employ Brahmans and worship the regubr gods. In most districts, indeed, degraded Kanaujia or Maitbil Brahmans serve the caste as priests in a somewhat irregular and intermittent fashion, being paid in cash for specific acts of worship and for attendance at maniages. Many Dosadbs, again, belong to the Sri Narayani sect, and some follow the J}{tn&it, or doctrine of Kabir, Tulsi Das, Gorakhnath, or Nanak. This enthusiasm for Religion, however, like the Satnami movement among the Chamars of the Central Provinces, appears to be a comparatively recent development, induced in the main by the desire of social advancement and existing side by siele with peculiar religious observances, survivals from an earlier animistic form of belief, tracos of which may perhaps be discerned in current Hindu mythology.

The god Bahu

Their tribal deity Rc'thu has been trunsformed by the Brahmans into a Daitya or Titan, who is supposed to cause eclipses by swallowing the sun and moon. Though placed in the orthodox pantheon as the son of the Danava Viprachitti and Sinhika, Rabu has held his ground as the chief deity of the Dosadhs. To avert diseases, and in fulfilment of vows, saorifices of animals and the fruits or the earth are offered to him, at which a Dosadh Bhakat Of Chatiya usually presides. On special ooc8sions a stranger form of worship i resorted to, parallels to which may be found in the rustic cult of the H.oman villagers and the votaries of the Phoonician deities. A ladder, made with sides of green bamboos and rungs of sword¬blades, is raised in the midst of a pile of burning mango wood, through which the Bhakat walks barefooted and ascends the ladder without injury. Swine of all ages, a ram, wheaten flour, and rice¬milk (lchir), are offered up: after which the worshippers partake of a feast and drink enormous quantities of ardent spirits.

His worship

Another form of this worship has been described to me by . . Dosadhs of Darbhanga and North Bhagalpur. On the fourth the ninth or the day before the full-moon of the montbs Aghan, Magh, PMlgun, or Baisakh, the Dosadh who has bound himself by a vow to offer the fire sacrifice to Rahu must build within the day a thatched hut (gaMm") measuring five cubits by four and having the doorway facing east. Here the priest or Bhakat, himself a Dosadh, who is to officiate at the next day's ordeal must spend that night, sleeping on the kLIsa grass with which the floor is strewn.

In front of the door of the hut is a bamboo platform about three feet £~'om the ground, and beyond that again is dug a trench six cubits long, a span and a quarter wide, and of the same depth, running east and west. Fire-places are built to the north of the trench, at the point marked cl in the plan below. On the next day, being the fifth, the tenth, or the full-moon day of the months mentioned above, the treneh is filled with mango wood soaked in ghee, and two earthen vessels of boiling milk are placed close to the platform. The Bhakat bathes himself on the north side of the trench and puts on a new cloth dyed for the occasion with turmeric. He mutters a number of mystio formulro and worships Rahu on both sides of the trench. The fire is then kindled, and the Bhakat solemnly walks three times round th e trench, keeping his right hand al ways towards it.

The end of the third round brings him to tho east end of the trench, where he takes by the hand a Brahman retained for this purpose with a fee of two new wrappers (dlwtis), and oalls upon him to lead the way through the fire. rfhe Brahman then walks along the trench from east to west, followed by the Bhakat. Both are supposed to tread with bare feet on the fire, but I imagine this is for the most part an optical illusion. By the time they start the actual flames have subsided, and the tr!lUch is so narrow that very little dexterity would enable a man to walk with his feet on either edge, so a not to touch the smouldering ashes at the bottom. On reaching the west end of the trench the Brahman stirs the milk with bis hand to see that it has been properly boiled.

Here his part in the ceremony comes to an end. By passing through the fire the Bhakatis believed to have been inspired with the spirit of Rahu, who has become incar¬nated in him. Filled with the divine or demoniac afflatus, and also, it may be surmised, excited by drink and ganja, he mounts the bamboo platform, chants mystic hymns, and distributes to the crowd tulsi leaves, which heal diseares otherwise incurable, and flowers which have the virtue of causing barren women to conceive. The proceed¬ings end with a feast, and religious excitement soon passes into drunken revelry lasting long into the night.

a. Bhakat's hut (gahba1')'

b. Platform (mac!uin),

c. Trench full of fire.

d. Fire.places.

e. Vessels of milk. /. Point from which Brahman and Bhakat pass through the fire. Next in importance to the worship of Rahu is that of various deified heroes, in honour of whom huts are erected in di:fferent parts of the country. At Bherpur, near Patna, is the shrine of Gauraia or Goraiya, a Dosadh bandit chief, to which members of all castes resort; the clean making offerings of meal, the unclean sacrificing a swine or several young pigs and pouring out libations of spirit on the ground. Throughout Behar, Balesh or Salais, said to have been the porter of Bhlm Sen, but afterwards a formidable robbl:'r in the Morang or Nepal Terai, is invoked; a pig being killed, and rice, ghi, 8weatmeats, and spirits offered. In other districts Ohoar Mal is held in reverence, and a ram sacrificed. In Mirzaplir the favoured deity is BindMchal, the spirit of ' the Vindhya mountains. In Patna it is either Bandi, Moti Ram, Karu or Karwa Blr, Miran, the Panch Pir, Bhairav, Jagda Ma, Kall, DeTI, Patanesvarr, or Ketti, the descending node in Hindu astronomy, sometimes represented as the' tail of the eclipse• dragon, and credited with causing lunar eclipses ; while Rahu, the ascending node, represented by the head of the dragon, produces a similar phenomenon in the sun. In none of these shrines are there any idols, and the officiating priests are. always Dosadhs, who minister to the Suclra castes frequenting them. The offerings usually go to the priest or the head of the Dosadh household perform¬ing the worship; but fowls sacrified to Miran and the Panch Pir are given to local Muhammadans.

In Eastern Bengal, says Dr. Wise, Sakadvipi Brahmans act as the hereditary purohits of the Dosadhs, and fix a favourable day for weddings and the naming of children. To the great indignation of other tribes, these Brahmans assume the aristocratic title of Misra, which properly belongs to the Kanaujia order. The guru, called Gosain, Faqir, Vaishnava, or simply Badbu, abstains :from all manual labour and from intoxicating chugs. His text• book is the Gyan¬sagar, or Sea of Knowledge, believed to have been written by Vishnu himself in his form of Ohatur-bhnja, or the four-arilled. It inculca.tes the immaterial nature of god (Nirakara), which is regarded by the Brahmans as a most pernicious heresy. In the Santal Parganas Dhobis and barbers serve the Dosadhs as priests.

Dosadhs usually burn, but occasionally bury, their dead and perform a Sdldcllt, more or Ie. s of the orthodox pattern, on the eleventh day after death. the female Dosadh is unclean for six days after child-birth. On the seventh day she bathes, but is not permitted to touch the household utensils till the twelfth day, when a feast (Mrahi) is given and she becomes ceremonially clean.

Social status and occupation

The social rank of Dosadhs is very low. No respectable caste . will eat with them, while they themselves, • besides eating pork, tortoises fowls and field-rats, and indulging freely in strong drink, will take food from any class or Hindus except the Dhobi and the specially unclean castes of Dom and Chamar'. Some of them even keep pigs and cure pork. Their characteristic occupation is to serve as watchmen (chaukida1's), and in this capacity they afford an excellent illustration of the Platonic or they rank among the most persistent criminals known to the Indian police. We find them also as village mes¬sengers (gomit), grooms, elephant-drivers, grass and wood-cutters, pankha coolies, and porters. They bear a high character as carriers, and are popularly believed to repress their criminal instincts when formally entrusted with goods in that capacity.

In South Bhagalpur the occupation of a groom is considered degrading, and a Dosadh who takes service in that capacity is expelled from the caste. This seems to be a purely local practice. In Western Bengal and Behar Dosadhs occasionally work as cooks and grooms for Europeans. Some of the chaukida1'S and goraits hold small allotments of land rent-free in lieu of the services rendered by them to the village,2 but generally speaking Dosadhs hold a low place in the agricultural system. Their improvidence and their dissolute habits hinder them from rising above the grade of occupanoy raiyat, and a very large proportion of them are merely tenants-at-will or landless day¬labourers.

During the Muhammadan rule in Bengal, says Dr. Wi e, Dosadhs and Bahalias served in the army, and when Ali Vardi Khan was Nawab Nazim the native historian stigmatises their licentious conduct as a disgrace to the Government. From the days of William Hamilton it has been generally believed that in the ear~y period of our military history" Bengali sepoys almost exclusively filled several of our battalions, and distinguished themselves as brave and active soldiers;" but, as is pointed out by Mr. Shore, for years before the battle of Plassey the troops in Bengal were chiefly composed of recruits enlisted in Hindustan. AccOl'ding to Mr. Reade, most of the sepoys who served under Lord Clive were Dosadhs, who of course cannot be regarded as Bengalis in the ordinary sense of the word. It must be remembered, however, that ::L few generations ago the word Bengal was used in a more extended and less accurate sense than is now the case, and it is quite likely that when Hamilton wrote of Bengali sepoys he merely meant to distinguish Natives of Hin¬dustan from the Madras sepoys (see artiole Telinga), who were largely employed in our early campaigns in Bengal.

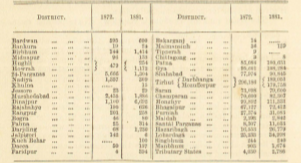

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Dosadhs in 1872 and 1881 :-