Jammu & Kashmir, history: 1846- 1946

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Mapping the state

The 18505: The Maharaja ensures that mapping takes place

Chandrima Banerjee, March 19, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 19, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 19, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 19, 2021: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, March 19, 2021: The Times of India

When the 1857 Rebellion broke out, the grand endeavour of mapping the country, the Great Trigonometrical Survey, had to come to a halt. And the first attempt to map Kashmir, as we know it today, would have been abandoned had Maharaja Gulab Singh not stepped in with money and hospitality when the 1857 Rebellion broke out, says new University of Cambridge research published by The Royal Society.

The paper, which “draws on (previously) unconsidered internal reports, proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and published results of the survey”, narrates how Kashmir was mapped systematically for the first time.

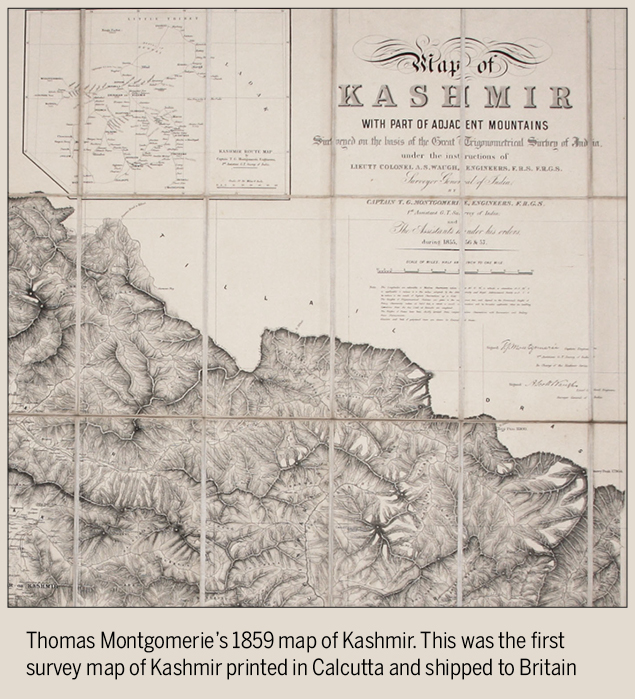

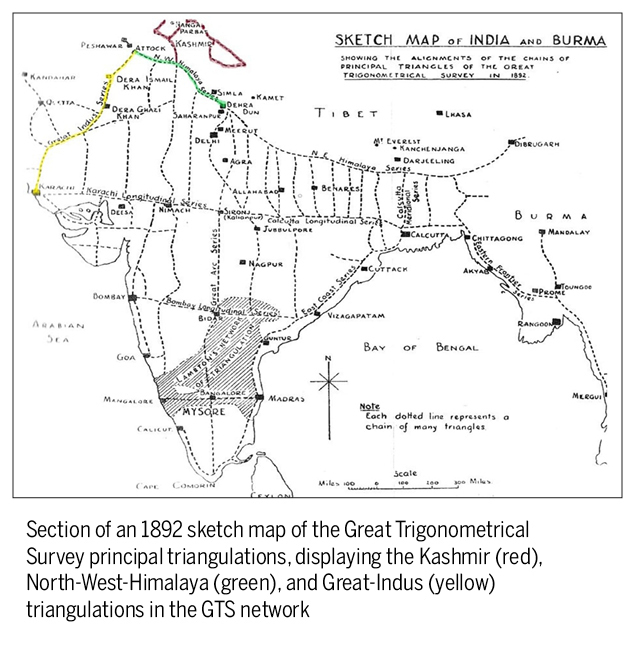

The countrywide survey had begun in 1802, and that for Kashmir in 1851. The author, Miguel Ohnesorge, said the survey reports for 1855-56, 1856-57 and 1857-58 had been clubbed together only in 1859 because of the 1857 Rebellion. It provided enough time for surveyors to decide how they would frame the 1855-1865 Kashmir survey. Internal notes that were quietly pushed off colonial records say how the survey was even possible — Dogra dynasty ruler Maharaja Gulab Singh financed it.

“This (earlier) draft not only explains that Maharaja Gulab Singh paid for the survey’s expenses that year but also tells us that Colonel (Thomas) Montgomerie, head of the Kashmir survey, stayed at Gulab Singh’s palace in Srinagar during the rebellion,” Ohnesorge said. Gulab Singh fell ill later that year and died.

This part was not included in the final 1859 version. “Silently ignored in (surveyor general Andrew) Waugh's later official report to the new colonial government, an internal note from May 1857 shows that the limited amount of surveying being performed was not financed by the EIC (East India Company), but by Maharaja Gulab Singh,” the paper said, quoting the note. That the British had, essentially, abandoned their great mapping exercise was not to be mentioned.

The erasure of Indians had happened on many levels. “There was no Indian surveyor employed … There were assistants who received monthly wages between Rs 5 and 6 … In comparison, even those British surveyors who only checked and corrected revenue surveys by Indians received Rs 400 a month — that is, 80 times as much as most of the Kashmir staff,” Ohnesorge said.

The mapping exercise also lay the groundwork for cultural attitudes and contentious gaps that spur conflict now. Aksai Chin, for instance.

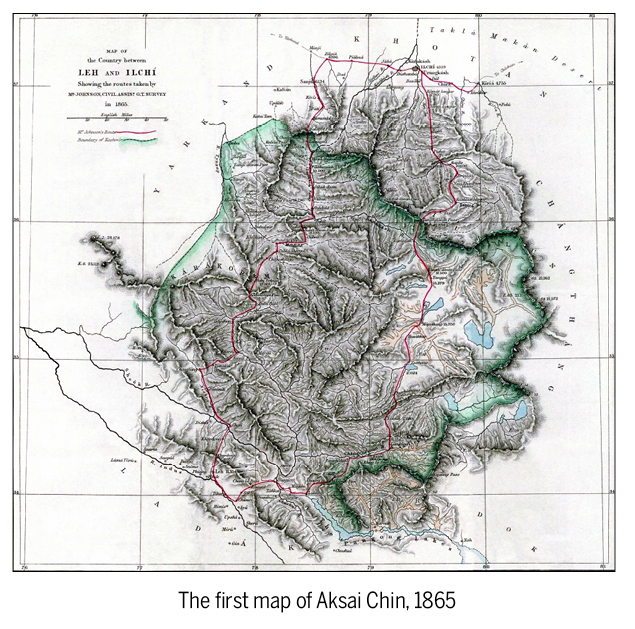

“The survey coincided with the beginning of disputes about Aksai Chin that continue until today. The main interests of the East India Company in Kashmir had always been a greater control of the trans-Himalayan trade from Tibet, China and central Asia,” Ohnesorge said. But Kashmir’s borders had been ambiguous and the colonial administration made use of that. “The Kashmir survey didn't yet properly cover Aksai Chin. In 1865 (when the survey ended), the surveyor William Johnson conducted a border survey that defined Aksai Chin as part of Kashmir, using earlier surveys as starting points. He presented this new definition to Ranbir Singh (Gulab Singh’s son and successor), who declared it official and stationed troops in the region.”

But this had been done without “consent” from Chinese imperial. “The Chinese had lost control over Xinjiang (across from Kashmir) after the Dungan Revolt in 1862,” Ohnesorge said. So, in the 1890s, the British gave back a lot of Aksai Chin to China. “But in 1911, the British went back to Johnson’s definition. The Xinhai Revolution had weakened China’s authority in the region. A modified version of Johnson’s line continues to be the basis of India’s claims to Aksai Chin.”

The survey, which was meant to create topographical and not revenue maps, was presented as a means to stake claim to territory. And for this, the surveyors were even more enthusiastic than the colonial administration.

In 1859, the year the first survey map of Kashmir had been printed in Calcutta and shipped to Britain, an assistant of the Kashmir survey, William H Purdon, wrote in his survey report that the Kashmiri “race” had to be “uplifted” because it was “wholly wanting in all the finer qualities for which they were formerly distinguished and have at length acquired the vices of slaves.” His argument, as that of other surveyors at the time, was that Kashmir had to be annexed. Onhesorge said this “culture in decline” argument had a broad appeal at the time.

“The region in particular, for many colonial officials, represented an example of a once great culture that had since declined, mostly due to Muslim rule. Of course, this is a simplistic vision of history that was popular precisely because of its utility in justifying British expansion,” Ohnesorge said. “As other historians … have analysed, there was considerable official sympathy towards Kashmir as a distinctively Hindu state with a subordinated Muslim population. It is hard to say, however, whether the surveyors themselves had any significant role to play in this broader dynamic. I see them rather as exploiting and radicalising it for their own purposes. Currently, one certainly finds similar paternalistic attitudes towards Kashmir.”

How India was mapped

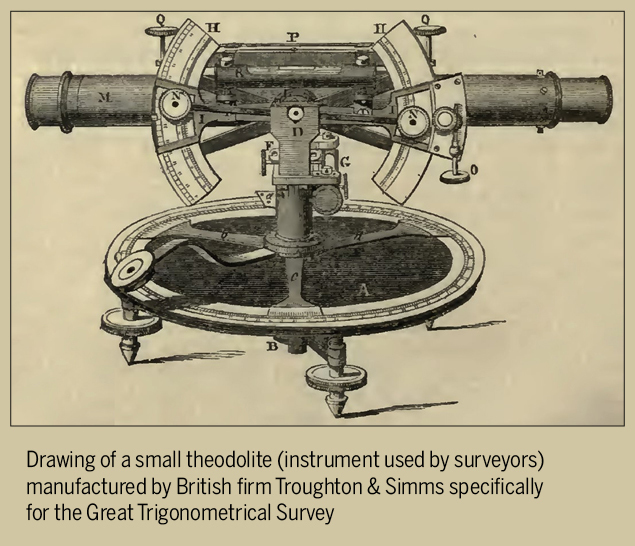

The Great Trigonometrical Survey began in 1802 by the British infantry officer William Lambton, under the patronage of the East India Company. He was succeeded by George Everest, and then by Andrew Scott Waugh. After 1861, the project was led by James Walker. It used the triangulation method, which is the process of determining the location of a point by measuring only angles to it from known points at either end of a fixed baseline, rather than measuring distances to the point directly.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

1840s-1935

Formation of J&K State

B.D.Sharma , The story of formation of J&K State "Daily Excelsior" 6/4/2017

Pakistan’s recent statements of her intentions to declare our State’s territory of Gilgit-Baltisan as her fifth province were soundly rebuffed by India. Hundreds of our brave men have laid down their lives to integrate these far-flung areas with our state and we have emotional attachment with this part of our state.Whenever we think of these far-flung areas, we are reminded of the interesting story at the back of formation of our state. Our state is a unique amalgamation of diversified and varied entities differing in climatic conditions to religious beliefs to cultural traits to cuisines. Weaving these areas in a single political entity was obviously an act of matchless diplomacy and statesmanship. Though some of these disparate and distinct regions had seen some semblance of unity for brief periods in the past also but the present shape of our State took its form in the middle of nineteenth century after the decline of Lahore Durbar. Its formation and evolution consists of engrossing series of episodes.

In 1840s almost the whole of our state fell under the suzerainty of Sikh kingdom of Lahore. The Kashmir valley was directly administered from Lahore through a governor. Jammu province was under the governance of the famous Dogra family of Gulab Singh except the Illaqa of Bhadewah. Major chunks of Ladakh region had also been conquered by the brave Dogra General Zorawar Singh.

The decline of Lahore kingdom started taking place after the death of the great Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh and the English made the most out of the emerging situation. Resultantly the first Anglo-Sikh war broke out where the Sikhs faced reverses and as per the treaty the Sikhs had to pay an indemnity to the English which the Durbar could not pay due to its precarious financial position. So the Durbar pledged the part of its territories including the area of Jammu,Kashmir and Ladakh to the English.

However Gulab Singh, the shrewd Raja of Jammu rose to the occasion and negotiated with the English the retrieval of not only his own territory but also the addition of beautiful valley of Kashmir. A treaty was accordingly concluded on 26th of Mach, 1846 at Amritsar between him and the English. According to this treaty all the mountainous country and its dependencies westward of river Ravi and eastward of river Sindh were transferred and made over to him for ever in independent possession. In consideration of the transfer he paid Rs. seventy five lakhs. In the process he was recognised the Maharaja for the said territories.Hence the formation of our state is an accident of history. Though this act of Gulab Singh is mired in some controversy yet in the words of K.M. Panikkar it is beyond any doubt that it is a master stoke of Maharaja Gulab Singh’s diplomacy.

In this way our state came into formation and it consisted of the hilly areas which were earlier, in the possession of Dogra family. It also included Chamba, Sujanpur and part of Pathankot, Kashmir valley, Hazara and Gilgit. A major chunk of plain areas falling in present Kathua, Samba and Jammu districts, however, did not fall under the ambit of the Amritsar treaty.

Incidentally a number of problems erupted soon after signing of the treaty which necessitated the redefining of the boundaries of the state. In 1847 the tribes of Hazara north of Muzaffarabad rose in rebellion. Though the same was supressed swiftly still the Maharaja thought it advisable to get rid of the ferocious and troublesome tribes. With the friendly Lawrence as Resident at Lahore it was accomplished easily and this ‘kohistan’ was exchanged with the plain and productive areas of Sucehetgarh (present R.S.Pura) and part of Minawar(K.M.Panikkar).

Another dispute erupted regarding the incorporation of Chamba including Bhaderwah in the state because the Raja of Chamba raised objections citing the exemption granted to his principality by the primordial Lahore Treaty. The matter was settled through arbitration by Henry Lawrence. Bhaderwah because of its geographical location was awarded to our State and in lieu of other areas of Chamba principality, our State got the area of the Jagirs of Lakhanpur and Chan Gran located near Kathua

So far as Sujanpur and part of Pathankot were concerned the Maharaja handed over these areas to the English in lieu of settlement and annual payment of perpetual pension to the disinherited rulers of Rajouri, Jasrota, Ramnagar, Basholi and Kishtwar. Our state retained a small chunk consisting of few villages namely Keerhian andGandial etc. across theriver Ravi.

Some areas ofLadakh, Baltistan and Gilgit remained under turmoil for many years even after their merger in the new State. The Dogras had to spend much in terms of men and material resources to keep their control over this vast tract of land for many years. They were able to establish complete control over Ladakh Skardu and Gilgit by 1850s and had also acquired varied degree of control over other frontier areas like Chilas, Ponial, Yasin, Darel, Hunza and Nagar by 1870 ( Panikkar, KM).

When the conditions stabilized in different parts of the state Maharaja Gulab singh breathed his last and it remained for his son, Maharaja Ranbir Singh to evolve an administrative setup in order to run the affairs of the state smoothly. According to Fredreric Drew, who remained in the employment of Maharaja as geologist and later Governor of Ladakh, Jammu province consisted of seven Zilas (districts) namely Jammu, Jasrota, Ramnagar, Udhampur, Reasi, Minawar and Nowshera. The designation of the officer incharge of the Zila was ‘Sahib-e-Zila’ , corresponding to present day Dy Commissioner. He had an assistant under him known as ‘Naib-e-Zila’. Each Zila had three to four Tehsils each headed by a Tehsildar.

Similarly Kashmir Suba’ was divided into six districts, Kamraj, Pattan, Srinagar, Shapian, Anantnag and Muzzafarabad. The ‘Sahib-e-Zilas’ of Kashmir Suba were under the Governor of Kashmir. The northern vast cold desert was divided into three Governorships namely Gilgit, Baltistan and Ladakh. Interestingly Zanskar area was not part of Ladakh and had been attached to Udhampur district. The three Governors exercised lot of powers . The Raja of Poonch, as a vassal, enjoyed autonomy but remained largely dependent and obedient to the Maharaja.

During the reign of Maharaja Partap Singh reorganisation of the administrative units took place and Jammu province was then divided into five districts namely Jammu, Udhampur, Jasrota(Kathua), Reasi and Mirpur. Similarly Kashmir province was divided into three districts viz. Kashmir South (Anantnag), Kashmir North (Baramulla) and Muzaffarabad. There were two frontier districts of Ladakh and Gilgit. All these districts were known as Wazarats and were headed by Wazir-e-Wazarats. There were internal jagirs namely Poonch, Bhaderwah and Chenani whose control was, later taken over by Maharaja Hari Singh in 1930s. The frontier Illaqas namely Punial, Ishkoman, Yasin, Kuh-Ghizer, Hunza, Nagar, Chilas continued to enjoy autonomy. In 1935 Gilgit was leased out to the English by Maharaja Hari Singh for establishing a garrison to obviate the Russian threat.

This was the position of our State in 1947 when cataclysmic changes took place. Pakistan sent its forces and tribals to annex the State forcibly. Maharaja opted for accession with India and the invaders were thrown out from large areas of Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh but vast areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Muzaffarabad, Poonch and Mirpur remained in illegal possession of Pakistan. Aksai Chin area of Ladakh was illegally occupied by China 1950s and Shaksgam area of the State was illegally handed over by Pakistan to China.

The administrative organization of units has also undergone a conspicuous shift. We have divided the part of state with us into two divisions Jammu and Kashmir. Jammu Division has ten districts and Kashmir Division has twelve districts. The Pakistan-occupied area has been divided into two politico-administrative entities namely Pakistan-Occupied J&K or the so-called ‘Azad Kashmir’ and Gilgit-Baltistan. The former has been divided into ten districts namely Mirpur, Kotli, Bhimber, Muzaffarabad, Jhelum Valley, Neelam, Poonch-Rawalakot, Haveli-Kahuta, Bagh and Sadhnuti and its capital city is Muzaffarabad. Chhamb niabat of old Bhimber tehsil was handed over to Pakistan in exchange of some strategic territories of Ladakh after 1971 war.

The other unit is Gilgit-Baltistan. It was previously known as “Northern Areas” . It remained under the administrative control of Pakistan through its Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and only in 2009 it was given some amount of autonomy. This area has also been divided into ten districts, prominent of which are Shigar, Skardu, Gilgit, Hunza, Nagar and Astore. Its capital city is Gilgit.

In this way about half of the State raised by Maharaja Gulab Singh is presently in our possession. The other half with two regions of Mirpur-Muzaffarabad and Gilgit-Balitstan being in illegal possession of Pakistan and Aksai Chin & Shaksgam regions in illegal possession of China.

(The author is former IAS officer)

1860s

Dogra expeditions to Dardistan

Col J P Singh , Dogra expeditions to Dardistan "Daily Excelsior" 8/7/2018

Akhnoor is the first place in J&K which tells us that the Dogra rulers consolidated the gains resulting from coronation of Raja Gulab Singh and Treaty of Amritsar and in this regard Dogras had plenty to do. Hostile activities of tribes of Chilas, Punial, Darel, Yasin and Chitral necessitated number of expeditions. Even when the Dogra army was pre-occupied with Northwestern borders, it had to provide forces demanded by the British, against 1857 mutiny, the 2nd Black Mountain Expedition of 1878, the 3rd Black Mountain Expedition of 1888, 1st and 2nd World Wars. Hence it is obligatory that the tales of tribulations of Dogra rulers and their soldiers be kept alive for the posterity. Yearly celebration of Coronation Day at Jeo Pota is a step in that direction.

While the history of formation of J&K by Maharaja Gulab Singh has been well documented, the subsequent period involving consolidation of this huge empire, stretching from Pamir Plateau in the North to plains of Punjab in the South, by his successors is perceived to have received much lesser attention. Maharaja Ranbir Singh succeeded Maharaja Gulab Singh in 1856. He out performed his visionary father in every aspect. Hence an effort is made to describe several expeditions undertaken to consolidate the vast empire that he inherited.

Maharaja Ranbir Singh was more inclined to consolidate and organize the dominions he had inherited rather than fancy for far flung acquisitions of territories. His military activities in Gilgit-Baltistan, may be seen to be conditioned by the British interests in Central Asia which were in conflict with those of China and Russia. Maharaja, who in attempting to consolidate his rule in adjacent regions was forced, in 1860, to renew the conflict in Dardistan. This area was vast landmass of various divisions, each big and small, forming separate republics. Most important of these were Punial, Nagar, Hunza, Ishkoman, Chitral, Yasin, Mastinj, Hasora, Darel, Tangir, Gor, Thalicha, Kotli, Chilas, Palus, Harban, Thur, Thank, Bamar and Palus. Chilas was the largest which lies astride Indus and Nanga Parbat. Its inhabitants were Baltis, Bhutte and Dard.

Maharaja Gulab Singh had no legal or moral right over these areas except for being an empire builder for which conquest of Dardistan was necessary for proper defence of Northwest frontiers. By 1840 he conquered Chilas, Gilgit and its dependencies. He got Kashmir in 1846 by the Treaty of Amritsar. In 1847 Raja of Hunza, incensed by encroachment of his territories by Dogra ruler, attacked Gilgit. Governor Nathu Singh retaliated and entered Hunza. He was however killed along with Raja Karim Khan of Gilgit and his force was routed. Gulab Singh sought British help which could not be provided because of British involvement in consolidating their positions in Cis-Satluj States and foreseeing an uprising in the truncated Lahore Kingdom. Gaur Rehman of Punial and Raja of Darel helped Hunza. Their combined force captured Gilgit thus doing away with control of Dogra ruler for a short spell of time. Maharaja Gulab Singh however dispatched two columns of Dogras, one from Astor and the other from Skardu. Gaur Rehman was defeated. Karim Khan’s son Muhammad Khan was recognized as Raja of Gilgit. Gen. Bhup Singh and Sant Singh were appointed administrators.

Chilasis, a Dard race, inhabiting a long valley on the West of Nanga Parbat, used to occasionally raid Astor valley for plunder of cattle and enslaving people. It was to prevent these raids, Gulab Singh sent a punitive expedition against Chilasis in 1851 under Diwan Hari Chand, Wazir Zorawaru and Colonel Baj Singh. The men and women of Chilas offered stubborn resistance as a result large Dogra force was destroyed. But by a great stratagem Dogras succeeded in reducing these people to some degree of obedience but not without suffering over one thousand dead and wounded. In 1852, Gaur Khan again attacked Gilgit with the help of Raja of Hunza. At that time Gen Sant Singh was commander at Gilgit Fort. Another fort Naupura, close by, was held by Gorkha Regiment under Commandant Ram Din and Gen Bhup Singh was commander of reserve force at Bhawanji and Astor. Gaur Rehman made a surprise attack and isolated and surrounded the two forts. Gen Bhup Singh advanced to their rescue with 1200 men. When he reached the bank of Gilgit River, he was surrounded. After desperate fighting for few days Dogra suffered heavy casualties and few who survived were taken prisoners and sold as slaves. Gilgit Fort met the same fate and fell in the hands of Dards and its occupants were killed along with all the Gorkha woman in the fort. Only one woman escaped and swam across the Indus and reached Bundi to tell the story. Thus the Dogras were expelled from Dardistan and Indus Valley. Gaur Khan once again recovered Gilgit and ruled it till his death in 1860. From the year these events happened, for eight years Dogra Kingdom’s boundaries remained confined to Indus. It was left to Maharaja Ranbir Singh to re-conquer Dardistan.

In 1860, he sent a contingent of 3,000 under Gen Devi Singh Narainia. Dogras crossed the Indus and attacked strong fortifications laid by Gaur Rehman Khan and thought to be impregnable. Gaur Rehman Khan died just before Dogras reached Gilgit. This news disheartened Dards who could not make a determined resistance. A cannon-ball pierced through the door of the fort which killed the Wazir of Gaur Rehman. This decided the fate of Gilgit. The Dogras occupied the fort after which their hold on Gilgit never ended. Ali Daud khan, descendent of the Gilgit ruler was made ruler with Gilgit as tributary of Dogra Kingdom. This settled the affairs of Gilgit in an appreciable manner. But holding Gilgit required reduction of adjoining territories of Yasin and Punial. The Dogra General decided to advance further to follow up the victory. Yasin was easily invaded on 16 September 1860. Instead of physically holding the distant province, Gen Devi Singh appointed Azmat Shah, son of old ruler of Yasin and first cousin of Gaur Rehman as Governor. After investing Punial, its deposed local Chieftan, Raja Isa Bagdur, who had fled his country and sought refuge at the Dogra Court at Srinagar, was reinstated. Isa Bagdur also acquired the territories of Ishkoman, previously a part of Yasin. Taming of Gilgit, Baltistan and Dardistan was accomplished by the Maharaja in 1860.

The arrangement made at Yasin didn’t last long. Azmat Shah was expelled from Yasin by Mulk Aman, son and inheritor of Gaur Rehman Khan. He fled for his life and reached Gilgit even before Dogra forces reached back. Thereafter for three years, Dogras didn’t disturb Yasin but continued consolidation of Gilgit and Punial which would later serve as spring board for his ‘leap forward’ policy in the unknown Dardland. Early in 1863, Ranbir Singh sent a punitive force led by Col Hoshiara to Yasin. Dards offered very little resistance at Yasin but collected at a place called Marorikot, about a day’s march higher up the valley. Dogras marched to Marorikot. Yasinis came to give a battle enroute. They were defeated and fled to hills with Raja Mulk Aman. Others fled to the fort where hand to hand fight led to indiscriminate slaughter. After losing, Yasinis accepted suzerainty of Maharaja of J&K. Yasin was placed under Mir Wali, brother of Mulk Aman who signed an agreement dated 4 September 1864 declaring his loyalty to the Maharaja. Yasin however remained a permanent trouble spot for many years to come.

Dogras advent into Dardlands made all the frontier tribes restless. Reduction of Yasin whipped Hunza people to harass trade caravans traversing the Hunza route for Pamirs. In 1866, Dogra forces were dispatched to Hunza. Nagar allowed Dogras to pass through. Dogra forces advanced along Nagar side of the river towards Hunza until they reached closer to Hunza fort. But found no crossing at the river. While the plans were being made for crossing the river somehow, ruler of Nagar broke the alliance with Dogras. Panic stricken Dogras retreated and returned to Gilgit disgracefully. Thereafter a formidable confederation was made through the efforts of Wazir Rehmat of Yasin, (same person who had two years prior paid his respects to Maharaja on behalf of Raja of Yasin), headed by Mulk Aman, ruler of Chitral. It happened due to Dogras retreat from Hunza and construed weakness.

In September 1866 an expedition was sent into Darel to inflict punishment on all the invaders as retribution for the last invasion on Gilgit. The main body under Wazir Zorawaru and Col Bije Singh went by the Naupura Ravine, which was exactly infront of Gilgit. The other column went up through a side valley from Singhal. The only opposition the main column met was from Aman-ul-Mulk of Yasin and his people, who had come to help Darelis and taken up defensive positions where a ravine debouches into the main Darel valley. Col Bije Singh, an experienced and wary soldier, scaled the steep ascent of the ravine and took the enemy by surprise who fled helter-skelter. After two days both the columns joined. No opposition ahead, Darel lay open to the Dogras. They stayed a week there. Elders of the region offered their submission and held negotiations. After getting guarantee of peace, Dogras withdrew after showing Darelis that their country was not inaccessible. The main force withdrew to Kashmir leaving a routine garrison at Gilgit. The frontier tribes gave him much trouble and several expeditions had to be sent against them from time to time which resulted in complete subjugation of all these republics and khanats and establishment of closer ties with Mehtar of Chitral. In 1867 restless Aman-ul-Mulk of Yasin again invaded Punial. The small Dogra garrison with Raja Isa Bagdur held out till Bakshi Radha Krishan arrived with troops from Gilgit and forced Yasnis to flee. This was the last Yasinis attack on the territories of Maharaja Ranbir Singh. A decade of conflict ended in 1870 with treaties and agreements with Rajas of Hunza and Maharaja. Within 14 years of his rule Maharaja Ranbir Singh had conquered most of the tribal principalities and brought them in his sphere of influence mostly by a show of force and by using one tribal chief against the other.

See also

Jammu & Kashmir, history: 1846- 1946