Kapurthala State, 1908

Contents |

1908/ Kapurthala State

This section has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Physical aspects

Native State in the Punjab, under the political control of the Commissioner, Jullundur Division, lying between 31 degree 9' and 31 degree 44' N. and 75° 3' and 75 degree 59' E., with an area of 652’ square miles. The population in 1901 was 314,341, giving an average density of 499 persons per square mile. The State consists of three detached pieces of territory, the principal of which is an irregular strip of country on the east bank of the Beas, varying in breadth from 7 to 20 miles, and measuring in all 510 square miles. It stretches from the borders of Hoshiarpur District on the north to the Sutlej on the south, while on the east it is bounded by Jullundur District. This portion of the State lies, for the most part, in the Beas lowlands, and is roughly bisected from north to south by the White or Western Bein.

The

Phagwara tahsil , which measures 118 square miles, is enclosed by

Jullundur District on all sides except the north-east, where it marches

with Hoshiarpur. The rest of the territory consists of a small block of

villages, known as the Bhunga itdka, which forms an island in Hoshiar-

pur District. Both these tracts lie in the great plain of the Do5b, which

contains some of the best land in the Province, and are traversed by

the torrents which issue from the Siwaliks, the most important of which,

known as the Black or Eastern Bein, passes through the north of the

Phagwara tahsll. The State lies entirely in the aHuvium, and the flora

and fauna resemble those of the neighbouring Dis-

Physical tricts. The climate is generally good, except in the

lowlands during the rainy season. The rainfall is

heaviest in Bholath and lightest in the Sultanpur tahsll. The average

is much the same as in Jullundur.

1 These figures do not agree with the area given in Table III of the article on the Punjab, and in the table on p. 410 of this article, which is the area as returned in 1901 , the year of the latest Census. They are taken from more recent returns. The density is taken from the Census Report of 190 1.

History

The ancestors of the chief of Kapurthala at one time held posses- sions both in the cis- and trans-Sutlej and also in the Bari Doab. In the latter lies the village of Ahlo, whence the family springs, and from which it takes the name of Ahlu- walia. The scattered possessions in the Bari Doab were gained by the sword in 1780, and were the first acquisitions made by Sardar Jassa Singh, the founder of the family. Of the cis-Sutlej possessions, some were conquered by Sardar Jassa Singh, and others were granted to him by Maharaja Ranjlt Singh prior to September, 1808. By a treaty made in 1809, the Sardar of Kapurthala pledged himself to furnish supplies to British troops moving through or cantoned in his cis-Sutlej territory ; and by declaration in 1809 he was bound to join the British standard with his followers during war.

In 1826 the Sardar, Fateh Singh, fled

to his cis-Sutlej territory for the protection of the British Government

against the aggressions of Maharaja Ranjlt Singh. This was accorded,

but in the first Sikh War the Kapurthala troops fought against the

British at Allwal ; and, in consequence of these hostilities and of the

failure of the chief, Sardar Nihal Singh, son of Sardar Fateh Singh, to

furnish supplies from his estates south of the Sutlej to the British

army, these estates were confiscated. When the Jullundur Doab came

under the dominion of the British Government in 1846, the estates

north of the Sutlej were maintained in the independent possession of

the Ahluwalia chieftain, conditional on his paying a commutation in

cash for the service engagements by which he had previously been

bound to Ranjlt Singh.

The Bari Doab estates have been released to the head of the house in perpetuity, the civil and police jurisdiction remaining in the hands of the British authorities. In 1849 Sardar Nihal Singh was created a Raja. He died in September, 1852, and was succeeded by his son, Randhlr Singh. During the Mutiny in 1857 the forces of Randhlr Singh, who never hesitated or wavered in his loyalty, strengthened our hold upon the Jullundur Doab ; and after wards, in 1858, the chief led a contingent to Oudh which did good service in the field. He was well rewarded ; and among other con- cessions obtained the grant in perpetuity of the estates of Baundi and Ikauna (in Bahraich District) and Bhitauli (in Bara Banki District) in Oudh, which have an area of 700 square miles, and yield at present a gross revenue of about 135 lakhs. Of this, 3-4 lakhs is paid to Government as land revenue and cesses.

In these estates the Raja

exercises no ruling powers, though in Oudh he is, to mark his supe-

riority over the ordinary talukdars, addressed as Raja-i-Rajagan. This

title was made applicable to the Raja in Oudh only, and not in the

Punjab. Raja Randhlr Singh died in 1870, and was succeeded by his

son, Raja Kharrak Singh. The present Raja, Jagatjlt Singh, son of

Kharrak Singh, succeeded in September, 1877, attaining his majority

in 1890. The chiefs of Kapurthala are Sikhs. Sardar Jassa Singh was

always known as Jassa Kalal ; but the family claim descent from Rana

Kapur, a semi-mythical member of the Rajput house of Jaisalmer, who

is said to have left his home and founded Kapurthala 900 years ago.

The Raja has the right of adoption and is entitled to a salute of 1 1 guns.

Sultanpur is built on a very ancient site, but the only architectural remains of interest are two bridges and a sarai. The sarai and one of the bridges are attributed to Jahanglr, while the other bridge is said to have been built by Aurangzeb. The two princes, DSra Shikoh and Aurangzeb, are said to have lived for some time in the sarai and to have received instruction there from Akhund Abdul Latlf, an inhabi- tant of the place.

Population

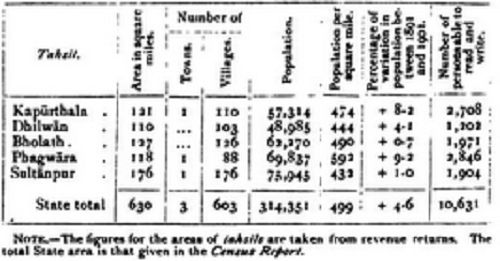

The State contains 603 villages and three towns : Kapurthala, Sul- tanpur, and Phagwara. There are five tahsils: namely, Kapur- thala, Dhilwan, Bholath, Phagwara, and Sul- op a ion. TANPUR) each with j ts head-quarters at the place from which it is named. The population at the last three enumerations was: (1881) 252,617, (1891) 299,690, and (1901) 3 I 4i35 I -

The main statistics of population in 1901 are given in the following table :—

About 57 per cent, of the population are Muhammadans, 30 per cent. Hindus, and only 13 per cent. Sikhs. The percentage of Muhamma- dans is considerably higher than in the neighbouring Districts and States. In density of population Kapurthala stands first among the Punjab States and is surpassed by only five of the British Districts. Punjabi is the language of practically all the inhabitants. Among the Muhammadans the most numerous castes are Arains (51,000), Rajputs (24,000), and Jats (14,000). Among Hindus, Jats number 15,000, and Brahmans 10,000, while the principal menial castes are Chflhras (sweepers, 21,000) and ChamSrs (leather-workers, 12,000). Sikhs are most numerous among the Jats (20,000) and the Kambohs (12,000). Nearly 68 per cent, of the population are dependent on agriculture.

The proportion is higher than in any Punjab District in the plains

except Hissar, and is slightly above the average for the States of

the Province. Most of the trade is in the hands ot Khattrls, who

number 7,000. Christians number only 39 ; there is no mission in

the State.

Agriculture

The greater portion of the Sultanpur, Dhilwan, and Bholath tahsils lies in the lowlands (Bet) of the Beas. Weils are used to irrigate the lands in the Bet, except in years of excessive floods. In the sandy tracts known as the Dona there are irrigation wells. There are a few strips of land where the soil is too saline for cultivation. The Kapurthala tahsll, as it includes only a small portion of the Bet, is the least fertile, and most of it lies in the Dona tracts. There are many wells in the tahsils but owing to the insufficiency of rainfall and the nature of the soil, the area irrigated by each well is small. The other portions of the State are fertile, and receive ample irrigation either from hill torrents or from wells.

The main statistics of cultivation in 1903-4 are shown in the follow- ing table, in square miles: —

The tenures of the State present no peculiarities. A few villages are owned by the Raja, but most are held by agricultural communities. The staple agricultural products, with the area in square miles under each in 1903-4, are as follows : wheat (200), gram (59), maize (47), cotton (9), and sugar-cane (15).

The system of State advances to agriculturists was established in 1876 by Mr. (now Sir C.) Rivaz, the Superintendent of the State, and the total amount advanced during the ten years ending 1903-4 was Rs. 2,13,000.

The cattle bred locally are of an inferior type and the best animals are imported. Efforts are being made to improve the local breed, and a number of Hissar bulls have been introduced. The horses, like those in other parts of the Jullundur Doib, are small ; but six stallions, the property of the State, are located at convenient centres, with the object of improving the breed. Mule-breeding has recently been introduced, and the State maintains 6 donkey stallions. A horse and cattle fair is held every year at Kapurthala town.

The area irrigated in 1903-4 from wells was 87 square miles; that

inundated from the overflow of the Befts and the Western Bein was

68 square miles. In the lowlands, the only kharlf crops that can be

grown are sugar-cane and rice. In the rabi harvest, the wheat and

gram are usually excellent. The floods from the hill torrents are often

held up by dams and spread over the fields for the irrigation of sugar-

cane, rice, &c, by means of small channels. Sometimes the water is

raised by means of jAa/drs, worked in the same way as Persian wheels.

In most parts of the State the wells are masonry, but along the rivers or

hill torrents unbricked wells are dug for temporary use, especially in

seasons of drought. In a year of light rainfall, such as 1899-1900, the

area watered by wells may rise as high as 109 square miles. The

area irrigated by a single masonry well varies from 5 acres in the sandy

tracts of the Kapflrthala tahsu to 7 acres in the Bet. The total

number of masonry wells in 1903-4 was 9,394.

There are five ‘ reserved ' forests in the State, covering an area of about 42 square miles. They are kept chiefly as game preserves, and no revenue is derived from them. The grass growing in them is used as fodder for the transport mules, State horses, and elephants.

Trade and communications

The State lies wholly in the alluvium, and the only mineral product of importance is kankar, which merely supplies local requirements. Sultanpur is famous for hand-painted cloths, which are made up into quilts, bed-sheets, jazams (floorcloth), curtains, &c, and in the form of jdzamSy curtains, and tablecloths are exported to Europe . phagwira is noted for its metal-work.

The State exports wheat, cotton, tobacco, and

sugar in large quantities. Phagwara has a large and increasing trade

in grain ; and as the grain market is free from octroi, it has attracted a

good deal of the trade which formerly went to Jullundur and Ludhiana.

The main line of the North- Western Railway passes through the Phagwara, Kapurthala, and Dhilwan tahsils, but Phagwara is the only town on the railway. The grand trunk road runs parallel to the railway and at a short distance from it. It is maintained by the British Govern- ment. The total length of the metalled roads maintained by the State is about 25 miles, and of unmetalled roads 35 miles. The most important metalled roads are those connecting the capital with the rail- way at Kartarpur (7 miles) and at Jullundur (n miles). The State maintains half of each of these roads. The British Post Office system extends to the State, which has no concern with the postal income or expenditure.

Cash rents prevail, and they are fixed according to the quality of the area leased. The rates vary from a minimum of 6 annas per acre for unirrigated land in the Kapurthala tahsil to a maximum of Rs. 9 per acre for land supplied by wells in the same taksil.

Famine

Tradition still keeps alive the memory of the famines of 1806 and 1865, when relief measures were undertaken by the State. The famine in 1 899- 1 900 was less severe, but on that occasion also the sufferers were relieved by the distribution of grain and of Rs. 1,323 in cash, though it was not found necessary to start relief works.

Administration

The Commissioner of the Jullundur Division is the Agent to the Lieutenant-Governor for Kapurthala. The Raja has full powers. The State pays Rs. 1,31,000 as tribute to the British Government. The chief secretary (Mushtr-t-Azam) deals with all papers pertaining to State affairs, which are to be laid before the Raja for orders, and conducts all correspondence with Government. He is also associated with the two other officials forming the State Council in carrying out the central administration under His Highness's control. For the purpose of general local administration the State is divided into five tahsils — Kapurthala, Dhilwan, Bho- lath, Phagwara, and Sultanpur.

The Indian Penal Code and the Procedure Codes are in force in the

State, with certain modifications. Legislative measures are prepared

by the State Council for the sanction of the Raja. The main pro-

visions of the Punjab Revenue Law are also generally followed in the

State.

Each tahsil is in charge of a tahsildar, who is invested with powers to dispose of rent, revenue, and civil cases up to the limit of Rs. 300, and also exercises magisterial powers corresponding to those of a second-class magistrate in British Districts. The appeals in rent and revenue cases (judicial and executive side) against the orders of the tahslldars are heard by the Collector, who also decides cases (revenue and judicial) exceeding Rs. 300. There is a Revenue Judicial Assistant who disposes of cases (revenue and judicial) exceeding Rs. 300 in the two tahslls of Dhilwan and Bholath. He also hears appeals against the orders of the tahsildars in those tahslls.

Appeals against the orders of

the Collector and the Revenue Judicial Assistant are preferred to the

Afushlr-i-AfaI y whose orders are appealed to the State Council, which is

the final appellate court in the State. Appeals in civil and criminal

suits against the orders of the tahsildars are heard by the magistrate

exercising the powers of a District Magistrate. He is assisted as a

court of original jurisdiction by an assistant magistrate having the

powers of a first-class magistrate. Appeals against the orders of the

magistrate and assistant magistrate lie in the appellate court of

the Civil and Criminal Judge, appeals from whose decisions are heard

by the State Council. In murder cases the Raja passes sentence of

death or imprisonment for life.

The old system under which the revenue was realized in kind was not done away with until 1865. The share of the State was two-fifths of the entire produce. On some crops, such as sugar-cane, &c, the State used to take its share in money. The revenue was actually collected by the State officials in kind, and stored up in the State granary and sold as required.

The land revenue at the date of British annexation of the Punjab was 5'7 lakhs. In 1865 the first settlement of the State was completed, and the demand was fixed at 7 lakhs. In 1877, during the minority of the present Raja, the assessment was revised, and the demand raised to 7' 7 lakhs. A further revision took place in 1900, when the revenue was raised to 8.7 lakhs. On this occasion the work was carried out entirely by the State officials. During the settlement of 1865, the first revenue survey was undertaken. It was completed in 1868. The rates for unirrigated land vary from 8 annas to Rs. 4 per acre, and for irrigated land from Rs. 3 to Rs. 9 per acre. The average rate for unirrigated land is Rs. 2-7, and for irrigated land Rs. 6-8 per acre.

Two of the State preserves, with an area of 2,200 acres, have been brought under cultivation. Occupancy rights in the greater part of one of these areas have been given to the cultivators on payment of a naz- ardna at the rates of Rs. 30, Rs. 37-8, or Rs. 45 per acre, according to the quality of the soil; while the remaining portion is given out to tenants-at-will on payment of a nazardna of Rs. 15 per acre. The total nazardna realized in 1903-4 from the tenants was Rs. 76,000.

The following table shows the revenue of the State in recent years, in thousands of rupees : —

Apart from land revenue, the main items of income in 1903-4 were :

Oudh estates (10.7 lakhs), stamps (2.3 lakhs), cesses (1-7 lakhs), and

j'dgirs in the Districts of Lahore and Amritsar (0.4 lakh). The total

expenditure in 1903-4 was 27.8 lakhs. The main items were: civil

service, including tribute (7-7 lakhs), household (6-4), Oudh estates

(5.4), public works (4.9), and army (1-9).

Spirit is distilled by licensed contractors in the State distillery. The rights of manufacture and vend are sold by public auction. A fixed charge of Rs. 25 is levied from each contractor for the use of the distillery, and a still-head duty of Rs. 4 per gallon is imposed on all spirit removed for sale. The receipts in 1903-4 were Rs. 21,000. Malwa opium is obtained by the State from the British Government at the reduced duty of Rs. 280 per chest, up to a maximum of 8 chests annually. The duty so paid is refunded, with the object of securing the co-operation of the State officials in the suppression of smuggling. The opium is retailed to the contractors at the rates prevalent in the neighbouring British Districts. Licences for the sale of hemp drugs are auctioned. Charas is imported from the Punjab and bhang from the United Provinces. The profit on opium and drugs in 1903-4 amounted to Rs. 11,000.

The towns of Kapurthala and Phagwara have been constituted municipalities. The nomination of the members requires the sanction of the Raj£. The municipality of Kapurthala was established in 1896 and that of Phagwara in 1904. There is a local rate committee for the State, which was established in 190 1-2, and is presided over by the Muster-i-Mal. The income in 1903-4 was Rs. 15,000, derived mainly from a rate of Rs. 1-9 per cent, on the land revenue. The expenditure is devoted to unmetalled roads and other works of utility for the villages.

The Public Works department was first organized in i860, and is under the charge of the State Engineer. The principal public works are the State offices, infantry and cavalry barracks, the college, hospitals, Villa Buona Vista, the great temple, and the Victoria sarai. The State offices cost 4«9 lakhs. A new palace is under construction.

The State maintains a battalion of Imperial Service Infantry at a cost of x-2 lakhs ; and the local troops consist of 66 cavalry, 248 infantry, 21 gunners with 8 serviceable guns/and a mounted body-guard of 20.

The police force, which is under the control of the Inspector- General, includes 3 inspectors, 1 court inspector, 5 deputy-inspectors, 15 sergeants, and 272 constables. The village ehaukiddrs number 243. There are six police stations,, one in charge of an inspector and five in charge of deputy-inspectors. Besides the police stations, there are fifteen outposts. The jail at Kapiirthala has accommodation for 105 prisoners. Jail industries include carpet and dart making.

Three per cent, of the population (5 males and 0-3 females) were returned as literate in 1901. The proportion is lower than in the adjoining British Districts and the States of Nibha and Faridkot, but higher than in Patiala and Jind. The number of pupils under instruc- tion was 1,815 m 1 880-1, 1,762 in 1890-1, 2,265 in 1900-1, and 2,547 in 1903-4. In the last year there were 27 primary and 5 secondary schools, and an Arts college at Kapurthala. The number of girls in the schools was 205. All the primary and secondary schools, except those situated in the capital, are controlled by the director of public instruc- tion, but the principal of the college is responsible for the schools at the capital. The course of instruction is the same as in British terri- tory. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 28,000.

The three hospitals in the State (the Randhlr Hospital, the Victoria Jubilee Female Hospital, and the Military Hospital) contain accommo- dation for 51 in-patients. There are also 4 dispensaries. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 71,642, of whom 984 were in-patients, and 1,991 operations were performed. The hospitals and dispensaries are in charge of the Chief Medical Officer. In 1904 the total number of persons successfully vaccinated was 5,739, or 18-2 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccination is not compulsory.

[State Gazetteer (in press) ; L. H. Griffin, The Rajas of the Punjab (second edition, 1873).]

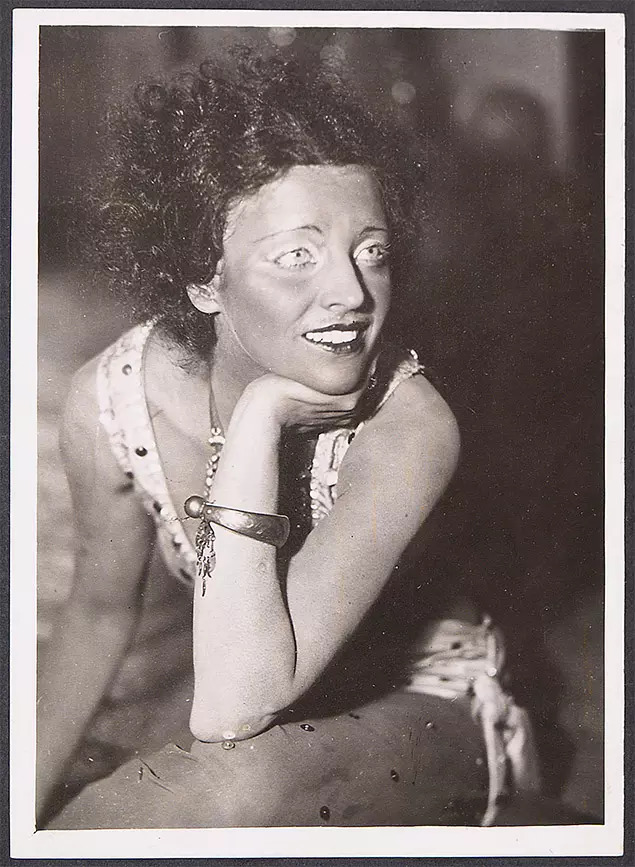

Rani Tara Devi (Eugenia Marie Grosupova)/ 1946

Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

By December 1946, the tall, slim woman with the wide-set eyes was a familiar sight at New Delhi’s Maidens Hotel. She had been staying there for about a month. Every day, she took her dogs out walking. But on the morning of the second Monday – December 9 – she came out of her suite alone, hailed a taxi and sped towards the Qutub Minar.

It was a long drive, the 13th-century tower – Delhi’s tallest building until then and for many years afterwards – lay outside the capital, about 20km away.

On arriving at the Minar, the woman left her handbag with the driver and started up the stairs. She must have been gone many minutes because the tower is over 72 metres tall – taller than a 20-storey apartment building – and not an easy climb even for someone in fine fettle.

The waiting driver might have stood leaning against his car, head bent backwards to see her emerge in one of the Minar’s balconies. He couldn’t have seen the look on her face when she appeared at the very top, breathless perhaps. But then, he would have frozen in shock as she jumped to death.

The Minar’s diameter grows from 9 feet at the top to 47 feet at the base. Some accounts say she fell on the edge of the second balcony. But newspaper reports of the day say her body was found at the base of the Minar.

A woman so beautiful that she had wowed Vienna’s elite on her first major stage appearance 11 years earlier, now lay smashed beyond recognition. Who was she? The contents of her handbag revealed she was Rani Tara Devi, the 33-year-old estranged wife of Kapurthala’s ageing maharaja, Jagatjit Singh.

After a post-mortem next morning, Tara Devi was buried at the Nicholson Cemetery near Kashmere Gate in Delhi, and forgotten.

A charmer on stage

But Tara Devi wasn’t her real name. Before the maharaja married her sometime in 1941 or 1942, she was just a foreign national staying in India as his guest. A Kapurthala state declaration submitted to the British in 1940 mentions her name as Engenie Marie Grosupova, which might have been a typist’s mistake. Eugenie is the more likely name.

The rani was a Czech national, born on January 22, 1914. Before accompanying the maharaja to India shortly before WW-II started, she had been a promising new dancer on Vienna’s most famous stage, the Burgtheater.

In his book ‘Maharani’, Diwan Jarmani Dass, who claimed to have been a minister in the royal families of Patiala and Kapurthala, says she was the illegitimate daughter of a Hungarian count. Dr Leon Pistol, who had been her guardian in Vienna from the age of 4 to 20 years, also hinted at this when he told the Canadian paper ‘Photo Journal’ that she was the daughter of “a very wealthy member of the Hungarian nobility”.

In 1935, Eugenie had landed a meaty role as Anitra in the drama Peer Gynt. She made at least two appearances, on June 8 and September 3 that year, and both times the press admired her for her beauty, femininity and dancing.

Austrian papers such as Die Stunde mentioned her as Nina Grosup-Karatsonyi. After her suicide, papers in America, Europe and Australia also used the name Nina Grosup, so did Pistol. So, Nina is what we’ll call her for the rest of this story.

A royal romance

After making a splash on the stage in 1935, Nina disappeared from it swiftly. In April 1947, four months after her suicide, Pistol told Photo Journal that the maharaja had been present at the Burgtheater during one of her performances. “Immediately after the performance, Nina’s mother called me to tell me that the maharaja wanted to bring them all back (to India) with him,” the article written in French says.

Another article published in the Sydney edition of The World’s News on August 23, 1947 also says, “On the opening night she received an ovation from the crowd, and a huge bouquet of roses from the maharaja of Kapurthala, who had been admiring the dancer from his box.”

Pistol said he opposed the maharaja’s offer because Nina had signed a three-year contract with the Burgtheater, but “the suitor-royal simply shrugged his shoulders and offered to buy out the contract in question for $20,000.”

Soon after this, Nina, her then 46-year-old mother Marie Grosupova, and a 64-year-old maid/governess named Antonia Kaura, “followed the Maharajah to Paris, London, and finally, to India”.

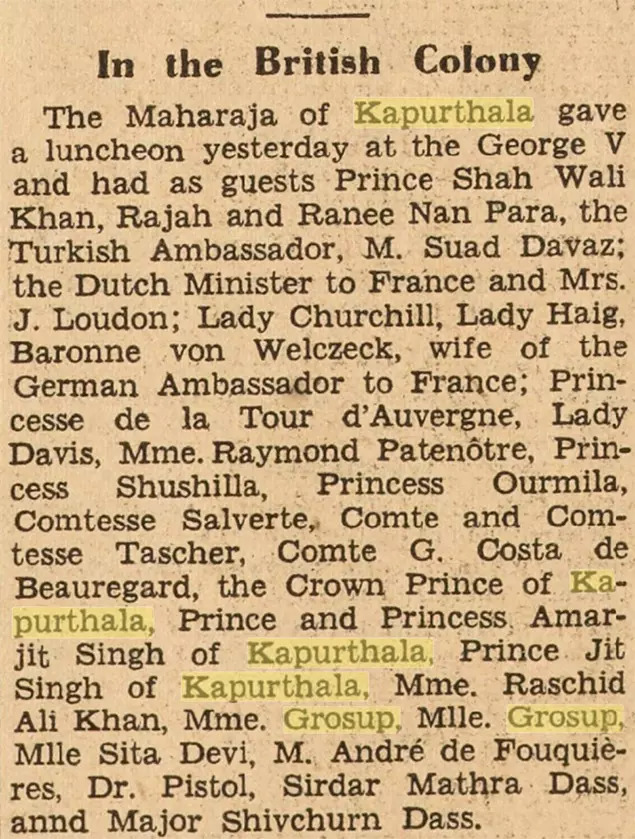

It’s difficult to verify Pistol’s claims in detail but the International Herald Tribune of June 28, 1938 describes a luncheon hosted by the maharaja at the George V hotel in Paris at which ‘Mme Grosup’ (Marie), ‘Mlle Grosup’ (Nina) and ‘Dr Pistol’ were among the guests. Clearly, Pistol’s story had a kernel of truth.

By the time WW-II started late in 1939, the Grosups and their maid were already installed at the Jagatjit Palace in Kapurthala. Nina and the maharaja weren’t married but Dass says the 67-year-old ruler was lavishing all kinds of expensive gifts on the 25-year-old former dancer. There must be some truth to this also as after her death, her possessions in the hotel suite were valued at many thousands of dollars.

When in February 1940, the British government asked the princely states to submit a list of ‘enemy subjects’ residing in their territory, Kapurthala declared the Grosup women (Czechoslovakia was under German occupation) were “guests of his Highness the Maharaja of Kapurthala”.

Unhappy marriage

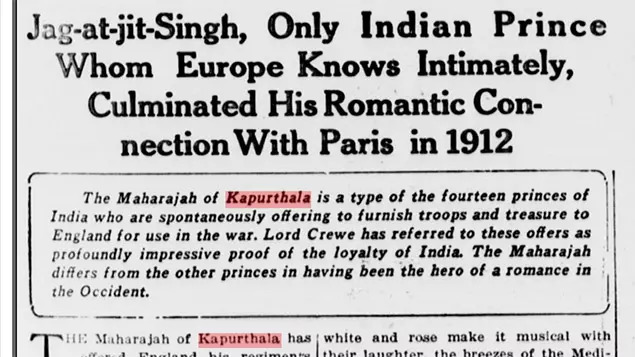

The maharaja was well-known in Europe and America and his engagements were regularly covered. Whole pages were written about him, so strangely his marriage to Nina doesn’t find a mention abroad. It’s true the press’s attention was occupied by the war, but still to ignore one of their favourites in this manner seems odd.

Maybe, the maharaja deliberately kept his sixth marriage low-profile, but it is a fact that Nina and he were married, and she was given the Indian name Tara Devi, because the question of “the grant of a British passport to Rani Tara Devi (formally Miss Grosup, a Czechoslovak citizen) wife of His Highness the Maharaja of Kapurthala” did come up in 1942.

It seemingly wasn’t a happy marriage for both parties. News reports after her suicide said they had separated in 1945 and Nina had been living alone. Pistol said she had even intended to visit America in December to settle there. The World’s News article said she had asked Pistol to buy her a house near New York City.

But much as she wanted to, Nina could not leave India. News of her death was covered well abroad but played down in India. The Madras edition of a prominent paper put it on its second page, below “Madras-Colombo rowing contest postponed,” and “Beedi workers’ strike in Malabar & S Kanara”.

Suicide or murder?

From the very first, Pistol said he suspected foul play in Nina’s death. He alleged that a month before she died, she had written to him saying, “Every day when I go out with my dogs somebody is asking me questions and follows me. I don’t know what he wants. I think it’s someone – a detective. But don’t worry.” She had also been jittery since her mother’s “mysterious death” a year earlier.

Pistol claimed Nina had left behind a fortune amounting to $150,000, including at least $100,000 in jewellery, “40 coats of furs and 52 trunks full of clothes”, all of which were his to inherit. “I will not rest as long as it is not clear whether the mother and governess died of natural causes and the maharanee committed suicide, or whether all three were murdered,” he is quoted in The Bombay Chronicle of September 22, 1948.

The National Archives of India has a record of an “Enquiry by Mr Leon Pistol, guardian of late Rani Tara Devi of Kapurthala, regarding her death in 1946,” filed in 1948. Four years later, in 1952, Pistol also sent a request to the PM “for assistance and advice regarding investigation into the mysterious death in 1946 of Eugenie Grosup, popularly known as Rani Tara Devi of Kapurthala.” But by then, the maharaja had died and the rani, whom few knew while she lived in India, lay completely forgotten.