Karachi: History 2

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Karachi

April 30, 2006

REVIEWS: City by the sea

Reviewed by Syeda Saleha

KURRACHEE, Past, Present and Future, is a series of books that covers the colonial rule — from the conquest of Sindh in 1843 by Sir Charles Napier to the creation of Pakistan in 1947. First published in 1890, the two volumes were reprinted to coincide with a spectacular exhibition at the Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi.

These volumes are, in fact, a treatise on Karachi written, firstly, to document the historical events and, secondly, to advocate the construction of a railway system connecting the gate of Central Asia and the Indus Valley with the native capital of India. The name “Kurrachee” is kind of intriguing, for we are accustomed to pronouncing and spelling it as “Karachi”. So why this change, one might ask. The author painstakingly explains: “Crochey, Krotchey Bay, Caranjee, Korachey, Currachee, Kurrachee and Karachi, are only a few of its many appellations and ways of spelling, the last being the official one, according to the Imperial Gazetteer of India, but it does not appear to have been, by any means generally adapted to the present time”, writes the author. He adds, “In deference to the almost universal concurrence in the form of the spelling and for the reasons above stated, Kurrachee has been adopted as the title of the present work.”

Narrating the occupation of Kurrachee by the British, the author points out that it resulted from military operations during the Afghan War of 1838. Sindh, then nominally independent, was subordinate to Kabul, to which it had been presented in 1756 by the Mughal court. The British faced with an extremely hostile Talpur dynasty, decided to send an expedition which anchored off Manora on February 1, 1839, and on February 3, the little fort there surrendered without firing a shot. Then, according to a treaty, the rulers of Sindh were asked to provide a warehouse at Kurrachee for military supplies.

In 1842, Sir Charles Napier was appointed to command the territories at lower Indus. Finally, Sindh was annexed in 1843 after a few battles. Thus, Sir Charles Napier became the conqueror of Sindh. He was the first governor whose fostering hands nurtured it with great care. Napier Road, connecting Kurrachee with Kiamari (Kaemari), was the first step towards the development of the place. It was this road that brought the town into immediate contact with the shipping facilities. And when the subcontinent was faced with political upheaval and demanded the intervention of the British government, its strategic importance as a seaport was realised.

Compared to Bombay and Colcotta (Kolkata), Kurrachee was nearer to the motherland and this led to the construction of a railway line, the Great State Railway System of the North West to which Kurrachee served as the sea-board terminus.

The volumes provide the transformation of Kurrachee from its infancy into a civil town of considerable size with its adjoining military cantonments. The efforts to develop it as a seaport provided unlimited opportunities. In a short time, foreign trade sprung up, which attracted not only indigenous traders but also foreign investment. The harbour developed and finally, an act was passed in 1886 under which the Kurrachee Port Trust was formed and made responsible for all the affairs of the harbour.

It would be wrong to say that the whole operation was executed smoothly. “Few harbours have given so much scope for official correspondence”, writes Alexander Baille. It was marked by negligence, indecision and red tapism. Same was the case with the construction of a railway line. “Till 1867,” writes the author, “the government had no interest in the railways.” However, 20 years later it was the property of the state. The Sindh Railway Line which started with a mere 100 miles between Kurrachee and Hyderabad covered a total length of 1,790 miles with its base at Kurrachee.

Presenting glimpses of Kurrachee before its annexation, the author says that there were no buildings possessing any remarkable features, with the exception of Chabutra or the Custom House. Gardens bordered the banks of Lyari for a mile, landing at or leaving the town was neither pleasant nor a dignified undertaking — the old civil servants and the newly appointed writer all had to undergo the operation of being carried by natives across the mud flats.

The concluding chapter of the first volume contains information about the population, administration and waterworks. The population, when first occupied by the British, was never clearly estimated. Some said it was 8,000 while others said it was over 14,000. According to the 1881 census, it was 73,560.

Regarding administration, we are told that the commissioner in Sindh had the powers of a lieutenant-governor. His recommendations had great weight. However, local interests were subservient to those of the state.

Waterworks was a problem, an issue which continues to this day. “The story of Kurrachee waterworks is both extraordinary and interesting,” says the author. It remained unresolved for 40 years and it was the municipal engineer James Strachen through whose efforts Kurrachee was provided with an ample supply of water. Drainage was another problem. The author says that if the proposal submitted by Strachen is approved, Kurrachee will probably be the healthiest city of the subcontinent.

To relieve the readers of the “uniform gravity and monotony” of the subject, the author provides a brief account of the then prevailing social, political and economic conditions.

The second volume is more about “present-day” Kurrachee which is, of course, also the past now. The author delves into a variety of subjects, from the history of Dak Bungalows and tramways to a number of buildings constructed by philanthropists, men of vision and the public works department. He acknowledges the contribution made by H.J. Rustomjee with regard to the construction of buildings on modern principles.

One also comes across the names of a number of roads and buildings which still exist physically or at least in one’s memory — Boulton Market and the Denso Hall Napier Road, Mcleod Road, Bandar Road and Preedy Street — to name but a few. The tramways are history now and the Dak Bungalows have been replaced by rest houses or hotels.

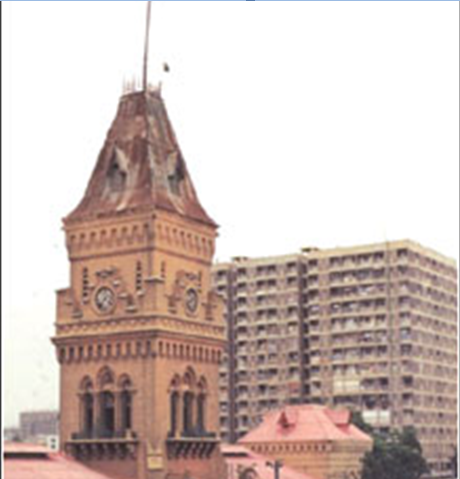

Chapter 11 of the book is very interesting and informative as well. It contains the history of buildings, which are regarded as national heritage now. Some of them include Empress Market (built in the “domestic Gothic style”, by Strachen and opened on March 21, 1889), The Trinity Chruch, Frere Hall and the Sindh Club, etc. One also learns that Clifton was once known as Mahdeva. How it received its English name, Clifton, is not known, though it may have been named after the birthplace of Sir Charles Napier. “Winter at Clifton! The very idea makes one shudder,” writes the author.

There is also mention of a brief history of the public institutions. Kurrachee had an indigenous system of education and had its vernacular schools under government control. This was transferred to the municipality when Kurrachee got its own school board in 1885. There were then, altogether, 10 schools, six for boys and two for girls, a mixed school at Manora and a night school. Out of these 10 schools, only five had a building of their own.

Included in this chapter are two tables which contain a list of primary schools and high schools. According to the list, the number of enrolment in primary schools was 39 and the costs incurred were Rs61,607. The list of high schools contain prestigious names such as Narayan Jagannath High School, Karachi Grammar School, St Patrick’s, St Joseph’s Convent School, Church Mission School and Sindh Art’s College, to name but a few. Most of them are still here.

Mugger Peer, known as Mango Pir also finds a place in the memoirs of A. F. Baillie. “It is the home of the sacred alligators, and the visit that I paid to them left so deep an impression on my mind, that for several nights afterwards, my slumbers were constantly disturbed,” recollects the author. He suggests, “Now that crocodile leather is employed in the manufacture of purses and cigar cases, I strongly recommend that Pir Mango be turned into an alligator farm.”

The feasts and festivals of Muslims, Hindus, Parsis and Christians have also attracted the author. “There are a great many holidays,” he complains. Ramazan, Muharram, Holi and Devali, Parsis’ New Year and Christmas festivities have all been mentioned. The carries Baillie’s personal opinion and observations.

Both the volumes of Kurrachee: Past, Present and Future have been beautifully reprinted. With their great photographs and valuable information, they will surely prove to be precious “jewels” in any library.

Kurrachee: Past, Present and Future Vol I ISBN 969-8837-10-8 147pp. Vol II ISBN 969-8837-16-7 197pp. By Alexander F. Baillie Dawn Group of Newspapers in collaboration with the Trustees of the Mohatta Palace Museum. Available with Pakistan Herald Publications Ltd., Haroon House, Dr Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi.

Karachi: Kolachi To Karachi

THE JOURNEY

By Maryam Murtaza Sadriwala

It stuns many to know that the thriving, vibrant, urban metropolis we lovingly call Karachi and which is home to more than 15 million people, was once nothing more than an obscure fishing village with a population of merely 10,000.

Karachi in Pakistan

In 1947, Karachi was made the capital of the new nation of Pakistan and its population of 400,000 people grew even faster. Although the capital later moved to Rawalpindi and then Islamabad, Karachi remains the economic centre as well as the financial and commercial capital of Pakistan and generates 60 per cent of the total national revenue. It is Pakistan’s hub of banking, industry, and trade. It boasts of being the nurturer of education, entertainment, arts, fashion, advertising, publishing, software development and medical research.

For quite some time, Karachi was dubbed ‘the city of lights’ and hailed as an economic role model for a developing country. Sadly, sectarian violence disrupted this throbbing, vibrant city in 1990s and resulted in the loss of thousands of innocent lives.

Today, Karachi is the largest city in Pakistan; the world’s second largest ‘city proper’ behind Mumbai in terms of population; the twentieth largest city of the world in terms of metropolitan population; the world’s third largest megacity.

The city is a tastefully colourful tapestry of rich history, vivid culture, throbbing entertainment and dynamic economy. It is the city where people come to make their fortunes, to better their lifestyles; to reach for the stars. It hosts the largest middle class stratum of the country.

Admittedly, it is pollution-ridden, congested and struck with the menace of load-shedding, yet for me, and 15 million more people, this is home. Anybody who has lived here once can’t help but reiterate Charles Napier’s words said as an ode to Karachi: “Would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur!”

Karachi: pre-history

By Azmat Ansari

Imagine hairstylists and dentists practising their respective professions 7,000 years ago in areas which today form Pakistan. A 7,000-year-old handmade machine for drilling holes into weak teeth and then filling the holes with resin is still in use. The chert-stone bit of the drill machine unearthed from Mehrgarh rotates 250 times per second. The modern drills rotate 500 times per second. In 7,000 years we have gained only 250 revolutions. What is stopping us from calling Pakistan the ‘first home of dentistry’?

If we look at the issue closely we will be justified in calling Pakistan the first home of women hairstylists as well. Almost seven millenniums ago, women in Mehrgarh wore brass frames on their shoulders with two long vertical spikes on either side for holding strands of hair upright, allowing their shoulders to stay bare so that their skin below their napes could feel the breeze. The women at the time also used tongs and clips to curl their hair. Some women wore wigs, perhaps the ones who had gone bald. We know all of this from the figurines that have been dug out from Mehrgarh.

If we want to learn more from these figurines, then it would appear that men wore what looked like neckties -- if not all of them wore them, then perhaps the royalty did. This should be food for thought for local tie-manufacturing firms. They could name a new brand of ties as Mehrgarh neckties to mark Visit Pakistan Year – 2007. While they do this, they will be saying that Europe and the rest of the world woke up to the idea of neckties millenniums later. Pakistan is the place where the concept of neckties was born.

Pakistan also appears to be the first place where organised cotton exports started. Some amount of cotton was also exported from Egypt, a contemporary civilisation of Moenjodaro, yet the scale of exports over there was not the same.

According to researchers, the tiny steatite seals with unicorns, fish and other symbols were the distinguishing trade marks that accompanied cotton bales that the boats carried from the river port of Moenjodaro to Dilman, modern-day Bahrain, and other close by African countries, so that the importers would know from which firm in Moenjodaro the bales of cotton originated and to whom exactly the payments had to be made. Can there be a better occasion to arrange a grand international conference on textiles and cotton exports to mark the Year-2007 somewhere in Moenjodaro or in Karachi?

Unfortunately, the most extraordinary discovery of the millennium, the existence of megalithic graves in Gulistan-i-Jauhar — which proved it beyond any doubt that the area which we call Karachi today was an inhabited one four to five thousand years ago — was played down. In fact, the very rock on which a huge grove cut by chert blades was made by ancient Karachiites was blown to bits by the owner of the residential plot in Gulistan-i-Jauhar on which the rock stood. He thought that the discovery of the rock grave would make the government confiscate his plot.

I know all of this because I was involved in the expedition.

A fruit of the expedition was the discovery of a crude handmade pitcher which was put on display at the Karachi museum. The discovery irritated some people. Why? A senior-person said, "If you can establish that Karachi was populated five thousand years ago, it will increase the stature of Karachi to unmanageable proportions. This some people will definitely resist."

It is not only that the megaliths have been discovered along the Pakistani coastline, they have been discovered on the coastline of India too, but India has done a very sensible thing with its megaliths. When similar graves were discovered around Bombay, the authorities designated the entire area as a megalithic park, which now attracts a lot of tourists. The laying of the foundation stone of a similar park will be an appropriate thing to do during the Visit Pakistan Year.

Dr. Rauf of the Geography Department discovered more than 50 pre-historic sites around Karachi. At least four names which can be publicised with reference to Karachi during the Visit Pakistan Year are Alexander the Great, Admiral Nearchus, Mohammad Bin Qasim and Ibn Batuta. There is more history and character to Karachi and other places in Pakistan than we know or care about. Perhaps we should learn marketing skills from other countries or our neighbours for our glorious land, as we seem to have taken them for granted in the 60 years of being.