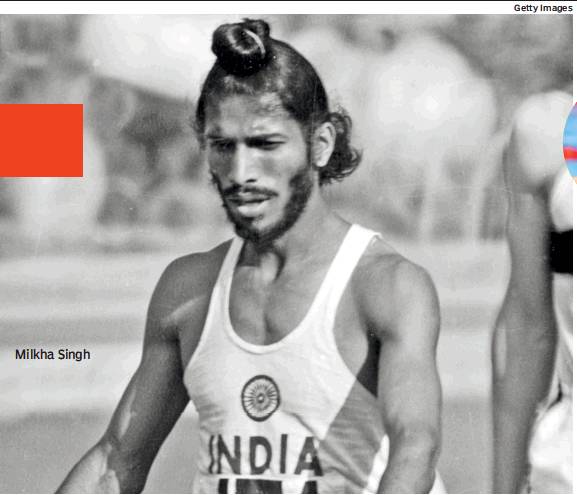

Milkha Singh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Achievements

A

By K Datta, A race that still stops time in India, August 29, 2017: The Times of India

When Milkha Singh narrowly missed a bronze medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics, television had not invaded our drawing rooms like it did during PV Sindhu's epic battle which sent heart-beats fluctuating with excitement.

In the 1950s and '60s, you had to wait for morning's newspapers for news about Milkha's exploits, perhaps primitive compared to today when news spreads instantly . Yet, the races which the Indian sport's first superstar took part in, at home or abroad, created a buzz whenever he stepped on a track.

Memories are still fresh of the days in September 1960 when Milkha made his way through the heats into the final of the 400 metres final. He began by clocking 47.6 seconds in the first heat, and followed up with running the quarter-final and semi-final heats in 45.5 and 45.9.

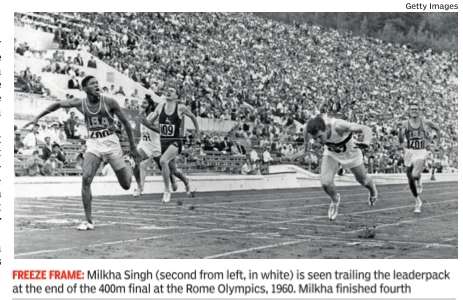

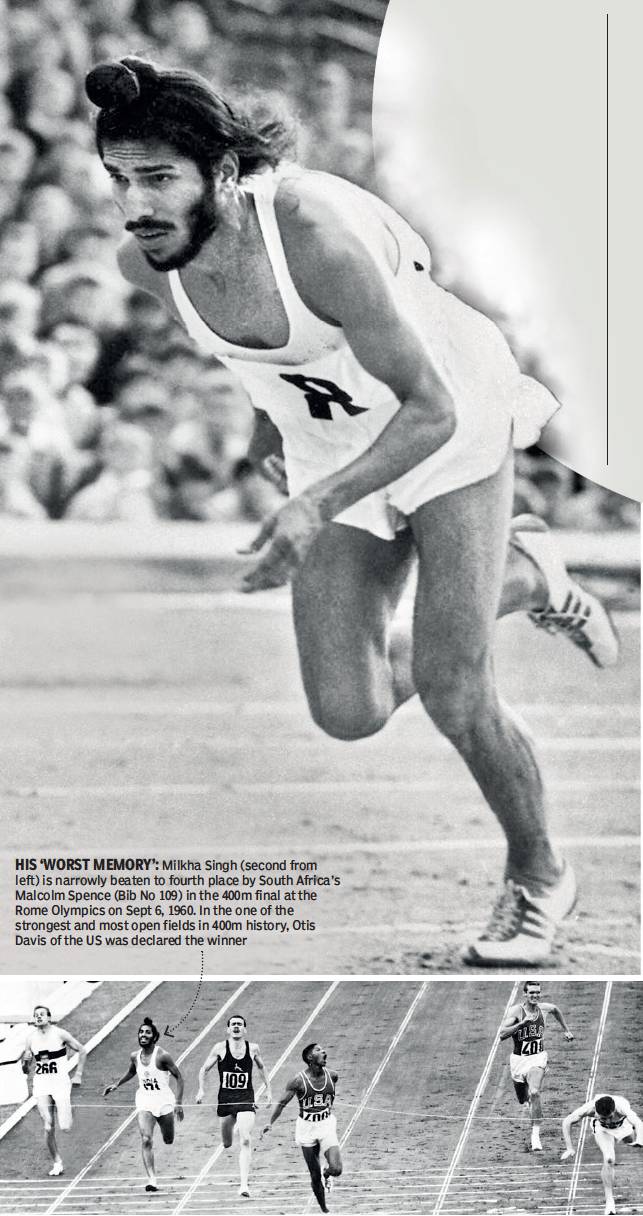

Milkha has admitted that he had difficulty falling asleep on the night before the Rome final. Nothing unusual. There were athletics fans back home who also went through a similar experience. But once the starter cracked his gun, our man, running in the fifth lane if memory serves right, was off to a promising start. For some reason, some called it an error of judgement, he slowed down a bit at the 250 metre mark. Otis Davis of the US, Germany's Karl Kaufmann, and Spence were there at the tape ahead of Milkha, who was fourth in 46.5 sec.

Milkha's hopes, as also that of his fellow-countrymen, of winning an Olympic track medal ended in painful disappointment, a pain which endures to this day.

B

Timeline

—Compiled by Tridib Baparnash, June 20, 2021: The Times of India

From: —Compiled by Tridib Baparnash, June 20, 2021: The Times of India

See picture:

Milkha Singh is narrowly beaten to fourth place by South Africa's Malcolm Spence in the 400m final at the Rome Olympics on Sept 6, 1960

1929 Born on November 20 at Govindpura, Punjab province (now in Pakistan)

1947 Moves to India post-Partition amid bloodshed in which he lost his parents

1951 Joins EME, Secunderabad

1953 Joins the Army after receiving training at EME centre

1956 Represents India in the Melbourne Olympics

1958 Wins 200m and 400m gold medals in the Tokyo Asian Games (Beats favourite Abdul Khaliq of Pakistan to win the 200m sprint in the Tokyo Asiad ) Becomes first Indian to win an athletics gold medal by winning the 400m event in the Commonwealth Games at Cardiff (Wales). Wins Gold medals in 200m & 400m at National Games in Cuttack

1959 Awarded Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian award, for his outstanding track achievements

1960 Becomes the first Indian to reach the final of an athletics event in the Olympics as he finished 4th in the 400m race. Earns the title ‘Flying Sikh’ bestowed on him by Pakistan’s President General Ayub Khan in December 1960 when he defeated Abdul Khaliq in a special 200m race at Lahore.

1962 Wins the 400m & 4 X 400m relay gold medals in the Jakarta Asian Games

1963 Marries Nirmal Saini, former captain of Indian volleyball team

1964 Finishes fourth in heat stages of 4 X 400m relay in Tokyo Games; Wins 400m Silver medal at Calcutta (now Kolkata) National Games

2001 Refuses to accept the Arjuna Award, highest award for sports in India, for lifetime contribution, saying he was clubbed with the awardees who were nowhere near the level he had achieved

2013 Autobiography (coauthored by daughter Sonia Sanwalka) The Race Of My Life published; based on the book, a biopic named Bhaag Milkha Bhaag was released the same year

2021 Tests positive for Covid-19, battles valiantly for a month and returns negative before succumbing to post-Covid complications

1951

K Datta, June 20, 2021: The Times of India

It was the same stage where the first Asian Games were held in 1951, called Irwin Amphitheatre before it became known as the National Stadium. Taking over the baton as the third runner in the 4 x 400 metres relay of the first Indo-Pak athletic meet, an event which was the idea of India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to get people to forget the bitterness caused by the country’s partition, a young Sikh runner overtook his Pakistani rival, looked back challengingly as he flew past to give India a winning lead before passing on the baton to the fourth and last runner.

A new sprinting star had emerged that day on the iconic track, now an artificial grass hockey pitch named after hockey great Dhyan Chand. Taking his first sprint into coming stardom that day was Milkha Singh, till then a virtual unknown. Among those who couldn’t help taking special note of that sprint was Pandit Nehru in his trademark russet sherwani, made all the more striking by a red rose.

Milkha is remembered as a simple man, a sparse eater who enjoyed “just a small drink of whiskey” in evening. “How, of all people, did I get this virus?” Milkha is said to have asked Gurbachan Singh Randhawa, the famous hurdler.

Posted in Secunderabad after being rejected by army recruiters on three occasions, Milkha said he got a princely allowance of Re 1 a day from the regimental funds to meet his milk bill because he would beat all others in crosscountry runs. “Ik rupaiya us waqt bahut hunda si.” One rupee was then a lot of money, Milkha explained.

That he trained unsparingly hard is known to all who dropped by at the National Stadium in those days. In fact, he was sometimes taken back, slung on the shoulders of fellow athletes, to his place in the barracks.

For Milkha training was a religion. When the National Stadium was taken up by activities other than athletics, Milkha could be spotted jogging on the gravel by the side of the road between India Gate and Tilak Bridge.

Milkha’s rivalry with Pakistani sprinter Abdul Khaliq is the stuff of story books. But it was friendly rivalry. Khaliq, a Pakistani POW after the 1971 conflict, is reported to have expressed a wish to meet Milkha. Did the meeting actually take place? Your guess is as good as mine.

1958 Commonwealth Games, Cardiff

Milkha Singh, As told to Biju Babu Cyriac, March 31, 2018: The Times of India

From: Milkha Singh, As told to Biju Babu Cyriac, March 31, 2018: The Times of India

I went into the 1958 Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, Wales, after winning two gold medals at the Tokyo Asian Games (men’s 200m & 400m) the same year. With worldclass athletes from Jamaica, South Africa, Kenya, England, Canada and Australia taking part, the competition in Cardiff was very tough. And, the obvious opinion among people in Cardiff was: ‘Arey India kya hai. India is nothing’.

I was not sure I could win a gold at the Commonwealth Games. I never had that kind of faith because I was competing with world record holder Malcolm Clive Spence of South Africa. He was the best runner at the time in 400m.

I will give credit (for the gold which I eventually won) to my American coach Dr Arthur W Howard. The first deputy director of NIS Patiala, Dr Howard was the athletics coach of the Indian team at the Games and planned the entire race strategy. He watched Spence running in the first and second rounds. The night before the final race, he sat on the charpai and my bed and told me: “Milkha, I understand only a bit of Hindi. But I’ll tell you about Mal Spence’s strategy and what you should do.”

The coach told me that Spence would run the first 300-350m slowly (even then his pace was good) and beat his rivals to the tape in the final stretch. “You should go all out from the beginning because you have the stamina,” Dr Howard said. “If you do that, Spence will forget his strategy (of beating everyone in the last few metres).”

I was on the outer lane, No. 5 (those days there were only six lanes) and Spence on the second in the 440-yard final at the Cardiff Arms Park stadium. Those days, lanes were allotted based on the number you picked from a bag and that’s how I got lane No. 5. We had to first run in the preliminary round, then the quarterfinals, semis and final.

I went all out from the start, running very fast till the last 50m. And, just as Dr Howard said, Spence realised that ‘Singh had gone too far ahead’. It was obvious to me that Spence had forgotten his own race strategy as he tried to catch up with me. He ran fast and in the end, he was about a foot behind me. He was close to my shoulders till the very end but couldn’t beat me. I finished in 46.6 seconds and he timed 46.9s. It was thanks to Dr Howard that I won the gold medal.

The gold medal was a big moment for India and I got calls and messages from a lot of people including Prime Minister Pandit Nehruji. He asked me: “Milkha, what do you want?” At that time, I didn’t know what to ask. I could have asked for 200 acres of land or houses in Delhi. I finally asked for one day’s holiday in India.

1960: Pakistan revisited

Tridib Baparnash, June 20, 2021: The Times of India

Haunted by the childhood memories of losing his parents and a few of his siblings during partition in 1947, Milkha Singh had once refused to travel to Pakistan, the same nation which bestowed him with the title “The Flying Sikh” in 1969.

Terrible images of dogs and vultures scavenging on mutilated bodies haunted Singh for years. He somehow managed to flee the country by hiding in a women’s compartment en-route to Delhi, where he spent his initial years by doing menial jobs. In 1960 after the heartbreak at the Rome Olympics, Milkha was invited to take part in the 200m event at an International Athletic competition in Lahore. He turned down the invite.

But Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru convinced Singh to travel to the neighbouring country, where he was expected to face Abdul Khaliq, who by then was an established name in the Asian roster.

The stakes were high as Pakistani media hyped the contest to a bilateral affair and posters of Khaliq vs Singh were posted across the country. But Milkha won the race comfortably. During the felicitation ceremony, Pakistan’s president Gen Ayub Khan told Milkha, ‘Milkha, you came to Pakistan and did not run. You actually flew in Pakistan. Pakistan bestows upon you the title of the ‘Flying Sikh’.

Singh later said that while the memories of his parents being butchered continued to haunt him, his return to Pakistan after 13 years and the love bestowed upon him there, helped change his perception of the people of Pakistan.

Excerpts from his autobiography

Milkha Singh, June 19, 2021: The Times of India

From The Race of My Life: An Autobiography published by Rupa Books ..

Soon after the National Games, our team had received an invitation from the Pakistani government for the Indo-Pak Sports Meet. What an ironic twist of fate. I was returning to the land where I was born, where I had lost my home and most of my family in the inhuman savagery that followed Partition. It was not the religious bigotry that troubled me, just the fear that the visit would revive those horrible memories. I did not want to go, but Pandit Nehru intervened, saying that this visit was for the honour of our country and that I was going as an ambassador for India. The others in our team felt as I did, as we reluctantly travelled to the border at Attari via Amritsar. The welcoming committee at the border greeted us warmly and then we were taken by bus to the Faletti's Hotel in Lahore.

Days before the Meet opened, headlines in newspapers as well as banners and posters carried large-print notices that said:

“Indo-Pak Athlete Duel Abdul Khaliq to meet Milkha Singh”

The Meet was declared open by the president of Pakistan, General Ayub Khan, at the newly constructed Gaddafi Stadium. There were more than thirty thousand spectators in the men's enclosure, and several thousand more of burqa-clad ladies in the women's. The general, other senior officials and their families sat comfortably in the President's box.

At this event I was once again pitted against my old opponent, Abdul Khaliq, whom I had defeated at the Tokyo games.

Consequently, the massive crowd's excitement levels were high as they eagerly waited for the moment when their hero would defeat me. In this Meet, too, the pattern of our victories was the same as at Tokyo-Khaliq won the 100 metres and I, the 400-metre race. The deciding race would be the 200-metre one. My teammates reassured me by saying that there was no way that I could lose, my technique was too finely honed and my timing was much better than the one at Tokyo. But as usual, on the day of the race, I woke up feeling feverish and bilious. I was shivering, either because I was unwell or by memories of those terrible days that still haunted me. Instead of succumbing or feeling sorry for myself, I forced myself to get up and go to the stadium. As I said to myself, over and over again, I had to win because a defeat in Pakistan would be a fate worse than death.

The Pakistanis had heard about me, but only because I had defeated their hero two years ago in Tokyo. They felt that the time had come for Khaliq to avenge his defeat. While the two of us were going through our warm-up exercises, there were deafening shouts from all the spectators: "Long Live Pakistan, Long Live Abdul Khaliq." The entire audience kept cheering for him as he walked in before me, followed by other Pakistani athletes and Makhan Singh, the only other Indian besides me.

At the starting line, I put down my bag, warmed-up and wiped the perspiration from my body with a towel. As we waited for the race to begin, a couple of maulvis, with flowing beards, skullcaps and carrying rosaries in their hands, encircled Khaliq. They blessed him, saying, “May Allah be with you.” Irritated by this blatant favouritism, I shouted, “Maulvi Sahib, we, too, are the children of the same God. Don't we deserve the same blessings?” For a moment, they were dumbstruck, and then one of them half-heartedly muttered, “May God strengthen your legs, too.”

There was pin-drop silence as we stood at the starting line waiting for the race to begin. The silence was oppressive. The starter, dressed in white shirt and trousers, a red overall, white peaked cap and black shoes, stood on a table behind us. He shouted, “On your marks,” fired the gun and the race began. The audience suddenly awoke and began to chant: “Pakistan zindabad; Abdul Khaliq zindabad.” Khaliq was ahead of me but I caught up before we had completed the first 100 metres. We were shoulder-to-shoulder, then surprisingly, Khaliq seemed to slacken and I surged ahead as if on wings. I finished the 200 metres about ten yards ahead of Khaliq, clocking 20.7 seconds that equalled the world record. My coach, Ranbir Singh, the manager and all my team members leapt to their feet in jubilation. I was embraced, thumped on the back and then lifted on to their shoulders as they expressed their happiness both vocally and physically. It was indeed a joyful day for India, but a terrible tragedy for Pakistan. Khaliq himself was so devastated that he lay on the ground weeping pitifully. I patted his back and tried to console him by saying that victory and defeat were part of the same game and should not be taken to heart, but he was too humiliated by the fact that he had been defeated before the eyes of his countrymen.

After the race, I ran a victory lap of the stadium, while loudspeakers announced: “The athlete running before you is Milkha Singh. He does not run, he flies! His victory will be recorded in Pakistan's sports' history, and we confer the title of ‘Flying Sikh’ on him.” It was General Ayub Khan who coined the title 'Flying Sikh', when he had congratulated me, saying. “Tum daude nahi, udhey ho (you do not run, but fly!)” As I passed in front of the women's section, the ladies lifted their burqas from their faces so that they could have a closer look at me, an incident that was widely reported in the Pakistani press.

And so, with this victory, I became the "Flying Sikh", a title that soon became synonymous with my name all over the world.

Excerpted with permission from The Race of My Life: An Autobiography (published by Rupa Books)

2017/ WHO’s ambassador (South-East Asia) for physical activity

August 11, 2017: The Indian Express

Sprint legend Milkha Singh has been appointed as the World Health Organisation's goodwill ambassador for physical activity in South-East Asia Region (SEAR), the global health body said

As WHO goodwill ambassador, Singh, also known as ‘the Flying Sikh’, will promote WHO SEAR’s non-communicable diseases (NCDs) prevention and control action plan which seeks to reduce the level of insufficient physical activity by 10 per cent and NCDs by 25 per cent by 2025, Poonam Khetrapal Singh, Regional Director, WHO South-East Asia said.

“Promoting physical activity for health is an important intervention, which is expected to get a significant boost in the region with the support of octogenarian Milkha Singh, a champion for the cause,” she said. According to her, an estimated 8.5 million people die due to non-communicable diseases every year in WHO South-East Asia Region and many of these deaths are premature and nearly all are lifestyle related.

Regular exercise and physical activity help reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases such as heart diseases, stroke, diabetes and cancer – that are now increasingly afflicting people across the world. An alarming 70 per cent of boys, 80 per cent of girls and nearly 33 per cent adults in the region report insufficient physical activity which is becoming a common feature of modern life, Singh pointed out.

WHO recommends at least 60 minutes of physical activity for children daily and 150 minutes of activity for adults weekly to stave off non-communicable diseases. Physical activity helps those aged 65 years and above to maintain cognitive functioning and reduce the risk of depression, the world health body said. To facilitate this, WHO has also been advocating with governments to create public spaces for recreational and organised sport. It has been advocating for physical activity as a “best buy” intervention for reducing the risk of deaths due to NCDs.

“Whatever be the age group, gender, physical ability, or socio-economic background, being physically active is an effective way to ensure a healthy and productive life,” the regional director said. With the support of Milkha Singh, we expect to promote and scale up physical activity in the region to be able to arrest and reverse the NCD epidemic, she said. Milkha Singh is a Padma Shri awardee and had won medals in athletics in Commonwealth and Asian games. He had missed a bronze medal by a whisker in the 1960 Rome Olympics.