Mirza Ghalib

These are newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

Ghalib

Fascination with Ghalib refuses to wane

By Rauf Parekh

IT is quite surprising that scholars keep on working on Ghalib and despite the fact that almost every aspect of his life and works has been done to death, new books on Ghalib keep on piling up with clockwork regularity. One wonders why these scholars don’t let Ghalib go or, rather, why Ghalib refuses to go away.

One of the reasons why Ghalib lives on is that his poetry remains relevant even today. Some of his couplets and letters are so fresh as though they had been written only recently. His Urdu, though written some 150 years ago and laden with Persian phrases, is strikingly closer to today’s parlance. In addition to his ability to see the eternal traits of human nature, his wit and gift for repartee make Ghalib’s poetry stand head and shoulder above his contemporaries’. His personality, his poetry and his letters have created an appeal that has not waned with the passage of time.

The fascination with Ghalib began with the publication of Altaf Hussain Haali’s Yaadgaar-i-Ghalib in 1897. Abdur Rehman Bijnauri’s famous tribute to Ghalib, originally written in 1921 as an introduction to Ghalib’s dewan, only whipped up that enthusiasm. After that a galaxy of Ghalib scholars, Ghulam Rasool Mehr, Imtiaz Ali Khan Arshi, Shaikh Muhammad Ikram, Qazi Abdul Wadood and Malik Ram being a few of them, established a tradition of thorough research on the poet who is ranked as one of the best in Urdu and, arguably, in Persian, too.

Probably their passion for Ghalib and his works, one feels, was a bit too much. But the scholars of the next generation such as Muslim Ziai, Rasheed Ahmed Siddiqi, Shaukat Sabzwari, Gian Chand Jain, Kalidas Gupta Raza, Qudrat Naqvi, Farman Fatehpuri, Rasheed Hasan Khan, Pir Hussamuddin Rashdie, Khaleeq Anjum, Abdur Rauf Urooj, Hanif Naqvi and Shams-ur-Rehman Farooqi are equally enchanted by him. And the tradition of fascination for Ghalib by no means ends here and Ghalib’s admirers are easily spotted in the new generation of Urdu scholars too.

Dr Shakeel Pitafi is one of them . He has done a great deal of research on the literature written about Ghalib --- known as Ghalibiyat or Ghalib Shanasi in Urdu. Dr Pitafi has surveyed the entire critical, research and creative literature written about Ghalib in Urdu in Sindh since 1947. No research, criticism, translation, compilation, annotation, dramatization, interpretation or commentary written about Ghalib in Sindh after independence has escaped his watchful eyes. Published in the 15th issue of Sindh University’s research journal Tehqiq, this 200-page research paper thrashes the topic of Ghalibiyat in Sindh. In addition to enlisting the literary magazines’ special issues on Ghalib, the paper provides the reader with an index that gives the details of published articles about Ghalib.

Dr Pitafi teaches Urdu at the Government College, Rajanpur. It is a pleasant surprise to see a scholar from a rural area doing such meticulous research. It also dispels the impression that only scholars belonging to big cities can carry out quality research.

The 15th issue of Tehqiq includes an entire section on Ghalib and other scholars who have contributed their research articles on Ghalib are Dr Anwaar Ahmed, Dr Aqeela Basheer and Muhammad Saeed. Jamshoro’s Sindh University’s Urdu department has been quite active since its inception and its former chairman Dr Najm-ul-Islam had launched Tehqiq, a quality research journal that set the standard for university research journals in Pakistan. Now Dr Syed Javed Iqbal is carrying this torch further and has brought out some issues of Tehqiq that are worth reading and preserving.

Critics agree that Ghalib’s letters are samples of elegant Urdu prose. But Ghalib took pride in his Persian not Urdu, though it is Urdu that has reserved a seat for him in the hall of fame. His Urdu letters have been edited and published but his Persian letters, though compiled in five volumes by different scholars, did not get the attention they deserved. With the decline of Persian in the sub-continent, it has become very difficult for a large segment of our literate population to benefit from these letters. It was imperative that these letters be translated into Urdu as they not only have invaluable biographical details about Ghalib but also provide us with a commentary on political, social and literary trends of an era living in the history books only.

Mushfiq Khwaja once asked Parto Roheela, another scholar who remains in Ghalib’s thrall, to render the letters into Urdu. A civil servant by profession, a poet by nature and a Raja by mood, Parto Roheela himself did not believe that he could finish the translation of even one volume of Ghalib’s translation, though he had an awe-inspiring command over Persian. But the unbelievable has happened and with the publication of ‘Kulliyaat-i-Maktoobaat-i-Farsi-i-Ghalib’ he now has the unique distinction of translating all the five collections of Ghalib’s Persian letters into Urdu.

Parto Roheela has been amply rewarded for burning the proverbial midnight oil as the National Book Foundation has published the book in a befitting manner and Dr Jameel Jalibi has paid glowing tribute to Parto Roheela in his preface. In his forward, Roheela has described some of the troubles he had to go through while carrying out this, as he puts it, ‘thankless’ job. Well, it is not a thankless job, as the entire Urdu world is thankful to him and all those who have had a lifelong affair with Ghalib will be eternally grateful to him and will salute him as has done by Dr Jalibi in his preface.

Ghalib

May 20, 2007

REVIEWS: Ghalib once more

Reviewed by Peerzada Salman

Poetry communicates before it is understood, so they say. And it is not controvertible. The reason for this is that all art is to be felt and not to be comprehended, at least in the initial stages of its reception. If that’s the case, then why should one try and analyse poetry, or all art for that matter? Well, perhaps to dissect the technique, not the creative process, that is consciously or inadvertently applied while creating art. As far as ‘deconstruction’ is concerned, it is a matter that belongs to a domain that’s extraneous to the book under review.

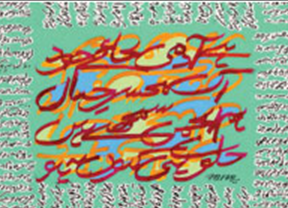

As hackneyed as it may sound, on the firmament of Urdu poetry, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib’s name outshines the entire galaxy. Save for Mir Taqi Mir, though it’s arguable, he can be readily labelled Urdu ghazal’s pathfinder. So when someone tries to nitpick Ghalib or comes up with ‘constructive criticism’ of his works or even presents an ‘intellectual critique’ of his couplets, it generates a lot of interest. And that’s exactly what happened when this reviewer got to read Kalam-i-Ghalib ka Fanni aur Jamaliati Mutal’a by Zaka Siddiqui, in which, apart from construing some of Ghalib’s known ghazals and couplets, the famous poet and erudite Nazm Tabatabai’s views on different facets to Ghalib’s poetry have also been compiled. It is, by any manner of means, and despite some itsy bitsy disputable critical comments, a scholarly work.

The book begins with a couple of chapters on information regarding the various kinds of verses and a cardinal aspect of Urdu poetry in terms of technique known as the ilm-i-urooz (the arrangement of strong and weak stresses in lines of poetry that produces the rhythm). The chapter on the ilm-i-urooz could have been more useful, particularly to the younger generation of verse-wielders, had it been written in a tad elementary fashion. Too much technical jargon with less examples make things rather convoluted, and puts off modern readers. Perhaps the book was compiled with an eye to the academia.

When someone tries to nitpick Ghalib, comes up with a ‘constructive criticism’ of his works or even presents an ‘intellectual critique’ of his couplets, it generates a lot of interest.

In Kalam-i-Ghalib ka Fanni aur Jalaliati Mutal’a, the brevity with which Ghalib’s rather intricate couplets have been paraphrased or interpreted is quite striking. On many occasions the master poet is praised for his unmatched genius — his terrific command over the Persian language, his ability to layer one word with multiple meanings, and the titillating wit (which assumes many shapes) that permeates his poetry, all receive commendatory comments. For example, the couplet, Shaad dil shaad o shaadman rakhyo / Aur Ghalib pe mehrban rakhyo is liked for the fact that despite the somewhat tautologous use of the word ‘shaad’, the line doesn’t sound ordinary or uninventive, in fact it gets semantically enriched. But what the author misses out on (which is forgivable) is the fact that Ghalib had a great ear for music. The intrinsic musicality in his poetry is often not discussed. The alliterative quality in the couplet quoted above is top-notch.

Then the book moves on to describing the tools that poets employ to embellish their works with. It defines, again not so profusely, things like metaphors, similes, paradoxes, irony and eloquence. And Ghalib had all of them in his repertoire and used them to near perfection.

Not that the book doesn’t contain instances where Ghalib falters in technique. There are quite a few examples given in Kalam-i-Ghalib ka Fanni aur Jamaliati Mutal’a where Ghalib has either committed a tiny metrical mistake or has forgotten to drop a certain syllable. But does it really matter? It’s like arguing over the fact whether William Shakespeare was a pseudonym used by Christopher Marlowe or did the great playwright even exist? Would that demystify the image of the bard in any way?

But on the whole the book is yet again an endorsement of Ghalib’s unique position in Urdu literature in general and Urdu poetry in particular.

Kalam-i-Ghalib ka Fanni aur Jamaliati Mutal’a

By Zaka Siddiqui

Scheherzade, B-155, Block-5, Gulshan-i-Iqbal, Karachi

info@scheherzade.com

257pp. Rs250

Ghalib and his city

Dawn July 01, 2007

REVIEW: Ghalib and his city

Reviewed by Asif Farrukhi

GHALIB once fancifully described himself as the nightingale of the garden yet to be created. But he came to be known as the poet of Delhi and it was with Delhi that he was identified. It is with reference to this city that Iqbal, arguably the greatest poet to be born after Ghalib, has worded his tribute to his great predecessor. Seldom have the city and the poet been so well-matched as Delhi and Ghalib. No wonder that later day figures such as William Dalrymple in his recent and ground-breaking study “The Last Mughal” have seen Delhi to be the centre of a cultural renaissance of sort, which was destroyed when the city fell to the British forces in the fateful year of 1857, a turmoil witnessed and recorded by Ghalib.

The post-1857 city found a rare chronicler in Ghalib who took up the art of chatting with friends through a regular stream of letters, which in the words of Intizar Hussain, form a proto-novel. Some critics have seen a line of progression from these letters to the development of Urdu fiction. Even if this were not the case, the fact remains that Ghalib in Delhi was very much in his element. And as such he pre-figures later-day writers like Naguib Mahfouz cocooned in his Cairo and Orhan Pamuk at home in the melancholy spirit of Istanbul, or even Intizar Hussain in Lahore.

This book offers a description of the city Ghalib lived in. In fact, I would describe it as a loose sally, a meandering in the city of the poet. The writer takes the reader through some of the main city areas and well-known landmarks, the lifestyle, some of the significant events, the major figures in the city’s literary and cultural scene and the even a peep inside the Red Fort where the last Mughal held court and where a rich cultural medley had grown around the ageing monarch.

In order to do so, he has culled together a number of first-hand sources, the major source being Ghalib himself who has a number of references to the city strewn through his prose and poetry. He has quoted amply from other contemporary sources including the delightful Bazm-i-Aakhir which offers a detailed account of everyday life inside the Qilla-i-Mualla. One surprising omission is the magisterial Waqiat Dar ul Hukoomat Delhi, penned by Bashiruddin Ahmed, and probably the most exhaustive topography written in Urdu about the city in question. The son of Deputy Nazir Ahmed, the late Moulvi sahib penned a number of novels, but this may well be his most important work.

The fact remains that Ghalib in Delhi was very much in his element. And as such he pre-figures later-day writers like Naguib Mahfouz cocooned in his Cairo and Orhan Pamuk at home in the melancholy spirit of Istanbul, or even Intizar Hussain in Lahore

This book can also be read as a miscellany of assorted facts and figures about Ghalib and his life in the city. From books and paintings in the city to culinary sources and the newspapers he would read, the references have been collected and rendered available to the reader.

There is a chapter on Moulvi Mohammed Baqar, one of the first journalists in Urdu who recorded the fading glory of the Mughal court. However, these glimpses are tantalisingly brief, and one wishes that some substantive details had been provided in order to make the case for a re-assessment or re-discovery of this forefather of later day war correspondents. However, this is a lapse in the format of the book that it does not stop its whirlwind tour to analyse or re-evaluate what it is breezing through.

The author has penned some travelogues, as the introduction by Professor Anwar Ahmed inform us. He has an interesting style and keeps the reader’s interest alive in the text, without being over-bearing. A number of plates and illustrations are included in the edition, which add to the value of the work. As it is a delightful work, designed to facilitate the reader, and not a treatise full of pedantic learning, there is no need to pick a quarrel with the more scholarly side of the contents. The one jarring thing about the book are the numerous typos liberally sprinkled throughout the text. For instance, on page 75, the list of Dagh’s shagirds begins with Masail Dehalvi instead of Sail Dehlavi and goes on to include Ahsan Marerwi instead of Marehrawi. If only the editing was as precise as the writing is meant to be.

Ghalib ke Zamane ki Dilli

By Dr Abbas Barmani

Sang-e-Meel Publications25 Shahrah-i-Pakistan, Lahore

Tel: 042-7220100

smp@sang-e-meel.com

224pp. Rs350

Ghalib: Persian

Ghalib’s Persian legacy

By Intizar Husain

The writings on Ghalib which have come to be known as Ghalibiyat are enormous. At the end of every year, we come across a large number of research articles and critical essays added to the ever-swelling stock of Ghalibiyat. And yet important parts of Ghalib’s writings seem to have failed to attract the attention of Ghalib specialists.

To be precise, it is only the Urdu works of Ghalib which have generally remained the focus of attention. And in here lies the irony — Ghalib attached more importance to what he had produced in Persian, and that was what he expected from his readers.

In fact, obsessed with his Ajami lineage, he was keen to be known in the first place as the inheritor of his Ajami legacy. He appears to have been very much in awe of the Persian poetic tradition and held the great masters of Persian poetry in high esteem. He yearned to be ranked amongst them.

This obsession on his part led him to treat his Urdu verse as something inferior to what he had, according to his own estimation, achieved in Persian.

Ironically, his admirers thought otherwise. They attached more importance to his Urdu verses.

Ghalib is, rightly or wrongly, an under-rated poet in Persian. He is solely indebted to his Urdu poetry that led to his status of a great poet. It is this area which has kept his admirers spell-bound and his critics deeply engaged in its study. Comparatively speaking, his Persian writings stand neglected while his prose suffered the most. It was only because of its historical importance that Dastanbu was chosen to be translated into Urdu. Other writings in general could not attract the attention of translators.

As far as Ghalib’s letters are concerned, he had been writing to his friend in Persian. It was only at a very later stage in his life that he chose to write in Urdu.

These letters had been rightly acclaimed as something new, leading to the breaking of a new ground in Urdu. They were read and re-read by scholars and general readers alike. Those who wrote about these letters and about the innovations of Ghalib in this respect, referred to his letters in Persian and about their being written in a traditional way.

Persian no longer enjoys the status it once did in our culture and in our literary tradition. The language is no longer familiar to our reading public.

It is therefore that Ghalib’s letters in Persian generally remained unread. Even the admirers of Ghalib did not care to ask for translations as they had formed an impression from what the critics had written about them.

Ghalib’s Persian letters had been rightly acclaimed as something new, leading to the breaking of a new ground in Urdu. They were read and re-read by scholars and general readers alike. Those who wrote about the letters and about the innovations of Ghalib in this respect, made special reference to these works in Persian.

They thought that these letters had little importance with respect to the study of Ghalib.

However, a few Ghalib scholars did care to make some translations from his stock of letters. These letters were collected at different times in five volumes and were published under five titles.

Different scholars at different times made attempts to translate them into Urdu. But no serious attempt was made to translate all of them in order to provide serious readers of Ghalib with an opportunity to make a comparative study of his Persian and Urdu letters and see the difference between the two.

It was left to Pertan Rohilla to make such an attempt. He had rightly asserted to be the first one to undertake the huge task of translating all these letters as collected in five volumes and to present them in one big volume along with their Persian text.

In his preface, Pertan Rohilla has explained about the care he has taken in translating these letters. He has taken pains to see that he had the authentic text of the letters before him.

On his stance as a translator, he tells us that he has been faithful to the text and has tried to convey in his translation the subtleties of thought as well as of expression.

This means that he has not tried to be facile in his translation in order to provide an easily readable version without caring to take into account the niceties and subtleties of expression peculiar to Ghalib.

Mr Rohilla has taken extra care while compiling this volume. Firstly, he has provided the Persian text of each translated letter.

Secondly, he has taken pains to provide us with the introductory information about the people who were addressed in the letters.

Pertan Rohilla is primarily known as a poet. Not content to be known as a ghazal writer alone, he has also made a name as a doha-writer. In addition to Urdu, he has been writing in Pashtau too.

A compilation in this language has won him a prize by the Writers’ Guild.

The present volume may be seen as a valuable addition to the list of his achievements.

Spiritual Radicalism

Sumit Paul, Dec 27, 2021: The Speaking Tree

Ghalib’s Poetry Reveal His Spiritual Radicalism

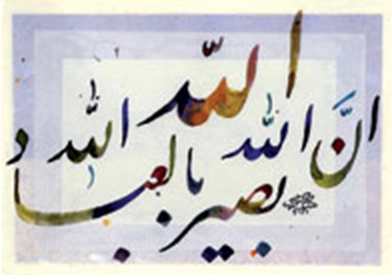

One of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib’s couplet that showcases his 'spiritual radicalism' goes like this: ‘Na tha kuchh toh Khuda tha, kuchh na hota toh Khuda hota/Duboya mujh ko hone ne, na hota main toh kya hota’ -- When nothing existed, Khuda did exist, I'd have been Khuda, had I not existed/ My very existence sabotaged that possibility, my non-existence would have made me Khuda. To the uninitiated, Ghalib was an agnostic, if not an outright atheist. But if you delve deeper, his poetry gives an impression of his profoundly spiritual bent of mind.

Ghalib was intrigued by human existence in the vast expanse of the kainaat, universe. Metaphorically speaking, the couplet defines Advait, non-dualism, of the Eastern consciousness, when the Creator and Creation are not separate entities but one. This couplet of Ghalib serves as a template for modern existential philosophy and solipsism.

Like Allama Iqbal, Ghalib also claimed to think in Persian. Poets with a Persian backdrop have invariably been influenced by the mystical poetry and ideas of the Sufis. At the same time, it's a known fact that Persian mysticism borrowed heavily from the Upanishads and Vedanta. Ghalib underlined that 'merging philosophy' of Eastern consciousness when he wrote, 'Ishrat-e-qatrah hai dariya mein fana ho jaana/Dard ka had se guzarna hai dava ho jaana' -- the glory of a drop is to merge itself in the vastness of the river/ When pain exceeds itself, it becomes its own remedy.

But towards the end of his life, the poet said, 'Khud ko bekhudi se bhi aage le gaya hoon/Khud hi khud mein nihaan ho gaya hoon' -- I've gone beyond the state of self-immersion/I'm lost in myself. This he wrote in a letter to his coeval poet Ibrahim Zauq, who was Emperor Bahadurshah Zafar’s teacher.

According to Ralph Russell, author of 'The Oxford India Ghalib: Life, letters and ghazals,' Ghalib represented true spiritualty that is humaneness and deals with humanity. That's why he could say: 'Bas ke dushvaar hai har kaam ka aasaan hona/Aadmi ko bhi mayassar nahin insaan hona' -- It's just difficult for everything to be so easy/Even a human is unable to evolve into a ‘humane being’. What Aldous Huxley thought of spirituality as 'humans practising humanity with humaneness' in the 20th century, Ghalib said the same a century before him.

A nominal Muslim, Ghalib's faith had the conviction of spiritual courage and uprightness of a believer: ‘Bandagi mein bhi woh aazaad-o-khudbeen hain ke hum/Ulte phir aayein dar-e-Ka'aba agar waa na hua' -- Even in worship, I'm so free and emancipated that I'll come back if the doors of Ka'aba don't open for me.

Lastly, Altaaf Hussain Haali Panipati, Ghalib's shaagird, student, wrote in his biography of Ghalib that the poet had completely repudiated the idea of tasawwuf, Islamic mysticism, as dimaghi futoor, an idiosyncrasy of the mind. In one of his Persian couplets, the poet dared ask Jalaluddin Rumi and Hafiz Shirazi, two stalwarts of Persian mysticism, 'Your brand of spirituality is delusional/Step out of your ivory towers and experience God, if at all God does exist.’

December 27 is Ghalib’s birth anniversary