Tattoos and India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Getting tattoos removed

2016: Indians regret their tattoos the most

From November 29, 2017: The Times of India

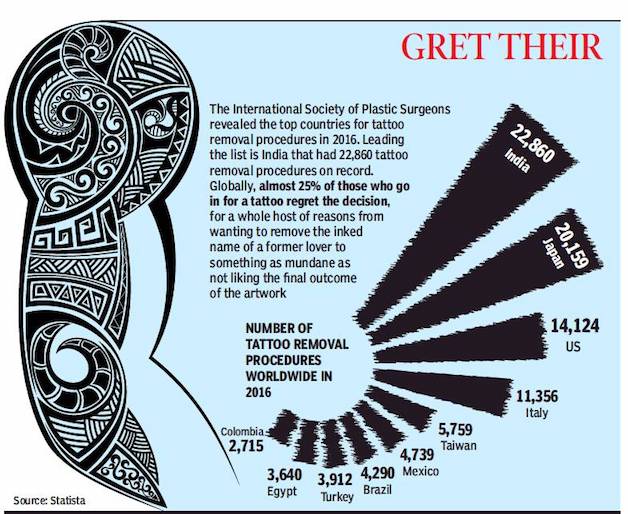

See graphic:

Number of tattoo removal procedures worldwide in 2016

The legal position

Tattoos can on right arm

Ajay Sura, August 23, 2023: The Times of India

CHANDIGARH: Getting inked can deprive one of a job, especially if the tattoo is on the right arm and the post applied for is in the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, reports Ajay Sura.

The Punjab and Haryana HC court recently dismissed a petition filed by a Hisar resident, challenging his rejection on the ground that he had a tattoo on the right arm, which is the saluting arm.

The petitioner, Monu, had applied for the post of constable in ITBP and had cleared all the steps, but was declared unfit in medical tests in August 2021. He moved HC against his disqualification and contended that he had got the tattoo removed, and therefore, shouldn't be denied appointment. Counsel for ITBP argued that removal of tattoo at a later stage was no ground to reconsider the case, since the advertisement for the post mentioned that there should be no tattoo on right arm.

Tattoos in Nagaland, Longwa village

As in 2022

Yudhajit Shankar Das, Sep 18, 2022: The Times of India

On a warm May afternoon in Nagaland’s Longwa village, 77-year-old Penjun Konyak is taking a nap with his granddaughter by his side. Looking at him you can’t imagine he earned his ‘stripes’ – tattoos covering his face and torso – on headhunting missions to what is now Myanmar.

About 400 km away, in Arunachal Pradesh’s Ziro valley, lives 80-year-old Tadu Sunku, who has never met Penjun but like him she has lines etched on her face. Both Penjun and Sunku are faces of the Northeast’s dying tattoo culture.

“No tribe in the Northeast practises tattooing now,” says Moranngam Khaling, 37, better known as Mo Naga, who travels to villages in Arunachal, Nagaland and Manipur to study their tattoo cultures and methods. He belongs to the Uipo Naga tribe of Manipur and is one of only three Indians to have featured in the book ‘World Atlas of Tattoo’. Women of Sunku’s Apatani tribe, for instance, traditionally tattooed a straight line from the forehead to the nose, and five smaller lines on their chins. But her 26-year-old granddaughter Tadu Oniya, a school teacher, sports neither. The tattoos are as beautiful as they are unique, says Oniya, but she would never get inked.

Tattooed Headhunters

Tattoos were a mark of valour among the Naga tribes, such as Penjun’s Konyak tribe. Tattoos on the face, neck and torso honoured and distinguished their brave headhunters. And some of the last surviving headhunters are among the Konyaks of Mon district as headhunting forays were reportedly made in eastern Nagaland even till the 1970s.

So, why did the tattoo tradition go out of fashion? Headhunting became a banned practice with the establishment of a formal administration and that adversely impacted the Naga tattoo culture. Mo says the introduction of a “foreign religion” was one of the biggest reasons. Tattooing continued even after headhunting was banned, as the tribes conducted mock headhunting sessions. But it stopped when the British started arresting anyone who was freshly inked, he says. Experts say Christian missionaries told the people tattooing was a “sin” as “they were defacing the image in which God had created them”.

Tattooed Women

Konyak men sported the more prominent tattoos but their women also got inked as they moved on from one stage of life to another – from marriage to childbirth – but no more. In faraway Bamin-Michi, Sunku’s village in Arunachal’s Ziro valley, women of the Apatani tribe had the more pronounced tattoos while their men had just three inked lines on the chin. “We got tattooed to look beautiful,” Sunku says.

“Apatani girls, when they were around 13 years old, used to be tattooed by older women of the village,” says 63-year-old Tage Yakha,who has tattoos and prominent nose plugs and earrings. She says thorns from a particular bush were used to etch the skin and insert ink made from soot, rice starch and pig fat.

Urban legend has it that Apatani women got tattooed to “disfigure” themselves, so that men from other tribes living around the valley wouldn’t abduct them. But Abang Gyati Rana, a prominent writer of the tribe, disagrees. “Apatanis didn’t start tattooing in Ziro Valley. The practice originated before we moved out of Tibet and continued during the course of that migration,” he says, quoting a centuries-old folktale.

In 1974, the Apatani Youth Association, a powerful community organisation, banned facial tattoos as girls who had them were teased and humiliated when they went outside the valley for higher education. A hefty fine of a mithun (a large bovine animal) on offenders ensured the rule was followed. Tattooist Mo points out the irony: “Imagine, the girls who waited to be tattooed to look beautiful being told when they grew up that they are disfigured and ugly.”

Valued Heritage

But Mo isn’t giving up on the art. “This generation is the first that has the education and means to revive the traditional ways of tattooing,” he says. After working as a tattooist in Delhi, he has returned to his village to set up a tattoo centre-cum-school. He plans to teach the traditional way of hand-tapped tattooing and has sown plants needed for the process.

“Tattoos of every tribe are unique as they are a marker of their identity and ancient aesthetics, their connection with nature, history and spiritual beliefs,” says Mo, adding, “The culture ministry needs to help save this heritage, else it will be appropriated by foreigners, repackaged and sold back to us in some time. ”