Ajmal Husain

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Ajmal Husain

A pioneer of Pakistaniart

Approaching eighty and still productive, age does not seem to have diminished Ajmal Husain’s ardour for painting and he remains one of Pakistan’s oldest practising artists. Salwat Ali traces the career of this Dhaka born artist, who skilfully combines his oriental heritage and western encounters

The secret of his vitality may well lie in the thrill and excitement that Ajmal Husain still experiences while experimenting with varied modes of expression. “Every medium provides a challenge and I cannot resist the impulse to work with something new,” declares the artist whose generative process is rooted in the belief that, “a creative mind is like a tree, it must continuously grow and bear new ideas - or else it will wither and die.

Urbane, soft spoken and sociable, Husain is widely traveled and well read and his art ethos emerges as a mixed palette of his oriental heritage and western encounters. Born in Dacca in 1925, he received his academic education in Calcutta. His career in journalism began in 1946 when he joined the Information Films of India. Later that year he became affiliated with daily Dawn as editorial cartoonist, in Delhi. Migrating to Karachi in August ‘47 with his late father Mr Altaf Husain, he resumed his assignment with the same paper in Karachi only to proceed to the US two years later for his Masters in Journalism. Here he also attended The Art Students League and the Cartoon Illustrators School to learn drawing and painting. On his return in 1952, Hussain settled down as editor of The Illustrated Weekly of Pakistan, a post from which he eventually resigned in 1968 to devote himself entirely to art.

A mural executed for the Pakistan Consulate in New York in 1950 was the beginning of his vocation as an artist. His initial expression centered on typical Bengali motifs of boats, river landscapes and fisher folk. Inspired by Zainul Abedin’s famine sketches he too made emphatic use of the black line to contour his figurative studies but his linear thrust soon assumed an abstract construct. Travels in the US, Europe and Japan, his study of Zen philosophy, Japanese calligraphy and Franz Kline’s broad black brushwork were major influences in this new style of work.

Internationally, Husain was among the first few modern painters from the east to exhibit in Europe soon after the Second World War. His first solo was in the German town of Bad Godesburg and he recalls, “Germany, at that time was still in ruins and the exhibition was held in Club Redoute that was reserved exclusively for the Allied Occupying Forces and no Germans were allowed to use it. The first time they were permitted in, was on the occasion of my exhibition.”

Other solo shows followed later in Geneva, Madrid, Tokyo, London, Paris, Munich and Milan. One of his paintings even earned a place of honour in the famous Salon d’Automne at the Grand Palais in Paris. Still walking down memory lane he observes, “Once I was accepted by the international salons and prestigious venues like the Commonwealth Galleries, many art magazines wrote about my work and that is when my paintings began to sell in Paris.” As Secretary General of International Association of Artists, for well over a decade Husain had the good fortune to attend the Association’s various art forums abroad and exchange views on art theories with modernists like Mark Tobey, Andre Mason, Hans Hartung and others. In the 1960 International Artists he was among the top ten international artists participating in a seminar in Vienna, sponsored by UNESCO, where he read a paper on “The Influence of Eastern Art on Western Artists and vice versa.” Today this issue is central to the subject of identity politics in art especially with relevance to third world countries.

Unlike the bustling art mecca that it is now, Karachi of the 50s and 60s was aesthetically nondescript where a motley collection of migrant artists tried to cobble together an art culture. Closely connected with the early art developments of fine arts in the city, Ajmal Husain was among the pioneers who laid the foundations of The Arts Council and initiated classes in art training. As Secretary General Karachi Fine Arts Society, he actively promoted art by organizing art exhibitions and related activities. For ten years he was Secretary General of the Central Institute of Arts and Crafts founded by his close friend, the late Ali Imam.

When Ajmal Husain held his first solo at Imam’s newly opened Indus Gallery in 1971 he had already been painting for the last twenty years. He was perhaps one of the few celebrated painters then, whose original work had not been widely viewed in Pakistan even though he had exhibited in most of the major capitals of the world. “Indus Gallery was not just a place where paintings were hung and exhibitions held.” He pointed out, “It had a distinct and somewhat mystic appeal to all those painters like me who played a part at the initiation of this gallery in a small house located in PECHS in the early seventies of the past century. It was my good fortune that mine was the first major one - man exhibition held at the Indus Gallery in 1971.

This exhibition was not only a precursor to many great things to come in future but it also set a style and standard that art galleries are trying to imitate all over Pakistan.” The art on show included some of his recent works executed in Paris. Discarding oils for acrylic based vapourised colour he had painted with a new sense of freedom. The attending elite were intrigued by the swirling rhythms of his dissolving images enveloped in diaphanous veils of luminous colour. The local press gave him wide coverage and hailed the paintings as poetic and symphonic. And even the hard to please Ahmed Parvez declared “I personally adore his work and respond to his message with ease.”

Disappearing from the art scene and resurfacing years later is something Ajmal Husain has done with relative ease. Living in Paris with his French wife and maintaining studios in London, Paris and Karachi enabled him to evolve as an artist on many fronts. His prowess was not just confined to the easel, other expressions included tapestry and rug designing, clay modeling, wood carving and glass painting. In 1983 a mural in lightweight plexiglass commissioned for Pakistan Burmah Shell House, highlighted the diversity of his oeuvre. An improvisation of the stained glass technique of preparing mosaic panels, the mural was a huge 11 by 18 feet structure which took Ajmal a year to plan, research and execute.

Based on the theme of energy the artists figurative composition of an eastern rural family and Mughal motifs was illustrated in the Art Deco technique, a preference that came out admirably well in his subsequent exhibitions. “The form of the 20’s with the force of the 80’s” is how he described this tenuous link with the decorative arts.

An old interest in oriental mysticism finally entered his art expression in a 1994 exhibition at Chawkandi Art, Karachi. Symbols of devotional art from ancient cultures like the Mayan, Aztec Tantric and Egyptian civilizations permeated his canvases in misty, soft edged contours. Isolating emblems from their original sources he stylized them to an alienated, exotic, visually imposing presence. He handled this aspect of the Art Deco mannerism to superb effect. No longer able to work with vapourised acrylic for health reasons he recreated his former rich but melting tonalities with finely layered oils. Some semblance of structure that was now visible in his canvases gained further strength in yet another solo in 1996 at Indus Gallery.

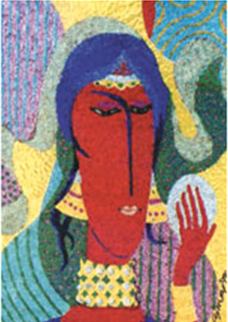

A significant number of collage works, including some memorable landscapes, in the cut and paste technique or simulated with chalk and oil pastels reminded one of Matisse’s brilliant cutouts. The Deco influence of flat bands and areas of colour was shown to superb effect in compositions like “Enchanted Gardens” where the figure, consciously refined and exquisite was placed in a sharp edged, rather mannered pose. His paintings took a dazzling turn when he exhibited his Icon Miniature paintings at Indus Gallery in 1998. Decadent art deco or at his surreal best Ajmal Hussain’s miniatures were ornately patterned, symbol saturated compositions of sparkling crystalline colours. Possessing the consistency of breadcrumbs glued together by a special process onto gold paper, their glittering tactility spoke of the artist’s considerable ability to manipulate surface effects and create fantasy art.

A close association with Indus Gallery and its curator Ali Imam has left a void in Husains life now that Imam is no longer in this world. Reliving the final moments he recollects “My last meeting with Imam was at the South City Hospital, Clifton only a few days before his grand departure. He was alone in his bed reading a book of Roomi’s poems. I sat on his bed holding his hand. He assured me soon he would be home and resume his gallery activities. He even proposed that I should get ready to have a show in December at the Indus Gallery since I had not had one in the past three years. Here was the indomitable Ali Imam lying in bed planning his gallery calendar! But when I got up to leave after about an hour of chatting, he looked into my eyes and said ‘It does not matter, I am ready to go whenever it happens.’ Unable to think of anything appropriate to say, I foolishly joked and said ‘Well you had better postpone your plan until you have organized my show in December.’ He smiled and waved his hand as I said goodbye.”

Reminiscing about another lost soul artist Laila Shahzada he remarks “she was a most sincere friend and dedicated painter, she was not in it for the glory or the money. And that is the greatest compliment I can pay her, she painted for the sake of painting.”

The proposed solo at Indus Gallery never did materialize but Ajmal Hussain continues to paint. Unlike today’s moralizing works riddled with gender conflicts and political tensions Husain creates pleasurable art with a touch of the extravagant and the surreal. Perhaps he also continues to paint for the sake of painting.