Babar, emperor

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Babar in Hindustan

By M.H.A. Beg

Text and photographs from the archives of Dawn

“FROM the year 910AH [1504-1505AD], when Kabul was taken, to 932AH [1525-1526 AD], I have wished for Hindustan. Partly because of my ameers’ lack of interest and partly because of my brothers’ lack of cooperation, the Hindustan campaign seemed impossible and the realm remained unconquered. But all such impediments have now been removed. None of my little begs [lower-grade ameers] and officers are able to speak out in opposition to my purpose any longer … We led the lashkar to Hindustan five times within the past seven or eight years.”

Thus according to the Babarnama, Babar’s struggle for Hindustan was planned and achieved, gradually, over a period of 21 years. Babar wanted to go to Hindustan because his great-great-great-grandfather, Amir Taimur, had been there and Babar carried his book Zafarnama, the book of victory, with him on this campaign.

As it was under his influence and control, Babar headed towards India through the KhyberPass. On reaching Nilab (a crossing on the river Sindh), he ordered the counting of his troops. Bakhshis counted it to be 12,000.

The route

Babar writes in Babarnama that after crossing the river he had to make a decision. The usual route spread from Lahore to Delhi through the plains, which did not get much rain that year. There was a possibility of water and grain shortage, however, the mountainous areas had received plenty of rain. He thus chose the route through Parhala (near Rawalpindi), Kalar Kahar (today’s Kalda Kahar), Sialkot and Kalanaur (near Gurdaspur). He may also have been influenced by the news of Daulat Khan pulling together a lashkar of 20 to 30,000 at Kalanaur. Daulat Khan was the governor of Lahore. He was removed from this post by Babar when he took over Lahore in 930AH (1523-1524AD).

Babar swiftly crossed the river Jehlum below the town, the river Chenab at Behloolpur, and the river Beas with the purpose of attacking Daulat Khan in a fort at Malot. Daulat Khan could not stand the onslaught and submitted while his son Ghazi Khan escaped to the mountains.

Babar found Ghazi Khan’s library at Malot very interesting. He had already heard of it and hoped it would have a valuable collection, which indeed it did have. He sent a few volumes of interest to his sons, Humayun and Kamran.

Ahead of him now laid the plains of India, all the way up to Bengal, but there were more obstacles in the way. The first of these was Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi, the Afghan Sultan who was based in Agra. On the South of Ambala, at a place called Sarsawa, Babar pondered and chose Panipat to be the place for the encounter.

Panipat

Panipat was a vast plain, where the river Jamna became broad. The town itself had many large houses and palaces, which could be kept for protection. According to Babarnama, Babar ordered trenches to be dug on the other side and large trees to be dumped in order to protect the left flank. He divided his lashkar into centre, right and left wings, along with an advanced guard and reserves at the back. In front of the lashkar, he kept arabas (carriages with guns) tied together with leather ropes. A space was left in between two carriages so that six men with match-locks could stand behind shields. Between all the sections, there was enough space left for shooting arrows and for quickly dispersing the troops in any direction.

Ibrahim Lodhi’s force appeared to be running around haphazardly. They were taken aback by Babar’s orderly and well-formed troops, which could very well be compared to a solid wall. This confused them and they didn’t know which way to attack. Still, being in overwhelming majority, they attacked fiercely and pressed mainly against the right wing of Babar’s troops. Noticing this, support was sent to the right wing from the reserves through the gaps between the troops. They surrounded Ibrahim’s lashkar from two sides. The arrows being shot from these gaps were deadly. Babar felt that they could prove to be the major weapon against the enemy in this encounter, that would bring him victory. Ibrahim was also killed in the battle, an occurrence which usually does not happen as sultans usually escape. Ibrahim Lodhi’s stand was extraordinary.

Kala Aam

Panipat is now a large city with great plains all around it which were bustling with commercial activity. A memorial has been established of three battles (Bairam and Himu, 1525-1556, Abdali and Marathas, 1761 and Babar and Lodhi) fought there. The city was locally known as Kala Aam — in memory of the last battle which took place near a mango tree. It is said that the tree had turned black with the blood of the soldiers killed in the battle.

The memorial, surrounded by a low stone wall, is situated about five kilometres away from the town. Here two plaques have been put up commemorating the first and second battles, along with a pillar that harks back to the third battle. There is also a small museum within the compound.

Ibrahim Lodhi lies buried in the city. There is a red-brick platform constructed on two different levels, on which rests his grave. The grave is plastered but there is no roof over it. A small plaque with words carved in Urdu indicates that it is the sultan’s final resting place. However, the area around it seems neglected. Occasionally a person or two shows up to recite the Fateha. Other than this there is no obvious Muslim presence in the city, for the main population comprises Punjabi Sikhs.

Kabuli Bagh Mosque

Though generally unknown and not mentioned very often by Babar himself, his lashkaris established a mosque while at Panipat. The lashkar and its bazaar must have stayed in a bagh where the mosque was built. To the Hindustanis, the foreigners staying there at the time of the battle came from Kabul, thus the garden was named Kabuli Bagh. This garden doesn’t exist anymore but the remnants of the mosque are still there. Its left dalan has crumbled down. According to Dr Ram Nath, who has devoted his life to doing research on Indian Mughal architecture and has written a four-volume book Mughal Architecture, the mosque was not made of stone and was not Babri in style. The building as well as the arches and dome were more Pakhtoon. These days its main dome is being repaired with the application of chemicals to save the crumbling masonry.

According to Babarnama, Babar marched 80 kilometres to Delhi and camped by the river Jamna. He stayed there for two days, visited the dargahs (Nizamuddin, Qutab) and the two famous ponds (Hauz Shamsi and Hauz Khas) along with the tomb of the kings (Balban, Khiljis and Lodhis), but does not describe them in his book. He also had a khutba (sermon) recited in his name after the Friday prayers. He had already dispatched Humayun to Agra, from Panipat, and he himself followed hurriedly. He was overwhelmed by the size of the country he had set out to conquer.

Poetic skirmish

Bayana was a strong fort situated on the southwest of Agra. Its ameer, Nizam Khan would not surrender to Babar. After exchanging messages, he did, however, make certain demands which Babar thought to be excessive. Immediately, Babar composed a rubai and sent it to him as a note of warning:

O’ Meer Bayana, do not wage war with a Turk, you know of our skills and courage, if you fail to listen and do not come before long, There is no need for me to explain the consequences that will follow!

The threat and persuasions worked in the end.

Disaffection in the lashkar

Like his predecessors, Babar also suffered from disaffection in his troops. Many of them were not comfortable with the hot tropical climate of India and did not want to stay put. The heat was blazing, as it was summer. Alexander of Macedon and Amir Taimur both decided to leave this land and take the troops back, but Babar proved superior to both in this encounter. He spoke to the troops and persuaded them through his poetry. He retorted to an ameer, Khawaja Kalan, who decided to go back after listening to a rubai:

O God, thank you for giving me Hind and Sind and other kingdoms, if you (Khawaja Kalan) do not have enough strength to bear the heat and want to face the cold, you have Ghazni.

Babar’s hoax

Immediately after Panipat, Babar distributed the wealth he had acquired among his sons, ameers, wives, tribes and troops. Every single person in Kabul and Warsak got a Shahrukhi. Gifts were also sent to Samarqand, Khurasan, Madina and Mecca. Babar gave away so much that people called him qaladar.

He also played a hoax on one of his old servants, Asas. Asas was sent an asharfi and upon receiving it, he was upset for three days about the meagreness of the present. As a result, when gifts were distributed in Kabul, according to special instructions, Asas was blindfolded and an asharfi was hung in his neck, which weighed 15 seers. Babar has not mentioned this story in any of his collections; however, Gulbadan Begum quotes it in Humayun Nama.

The Rana

There were still contenders of power lurking around, two of whom were immediate threats. Rana Sangha was in the southwest of Agra and Afghan ameers of Ibrahim Lodhi in the east. They had revolted while Ibrahim was in power. The ameers were far away but Rana had marched up close.

Rana Sangha had been proactive. He crossed the dry plains from Chitor towards Agra in 933AH (1526-27AD) and stayed at Bayana. Babar moved from Agra to Sikri and chose a lakeside at Khanwa, in the west of Sikri. His men were surprised at the speed with which Rana moved. There was also a fear among the troops as the astrologer Mohammad Sharif’s predictions were not favourable. This was also the first time that Babar faced a Hindu opponent.

Babar assumed the role of a Muslim fighter and jihadi against an “infidel”. He renounced drinking, abolished taxes on Muslims and in an act of philanthropy, ordered the construction of a well. Near that well, he shed wine laden on three rows of camels brought by Baba Dost from Kabul. All the glasses, cups and containers were also shattered.

Khanwa encounter

On the eve of the battle, Babar spoke to his men encouraging them to be fearless, persuading them to fight till their last breath as life and death were in the hands of the Almighty. The plan and organisation of his lashkar appeared to be on the same pattern as was in Panipat. Babar, unfortunately, left the description of the organisation and the battle to Shaikh Zain. Zain was a Persian scholar who used all the power of his vocabulary, rhetorical words and bombastic sentences to motivate the troops. It appears that the rush of Rana was on the right wing of Babar. Babar used the reserve force to support that wing and also utilised it to surround Rana from all sides. Then he pushed towards the centre, which caused chaos amongst Rana’s men. They could not stand the onslaught and retreated. Rana escaped wounded.

Bagh-i-Fatah

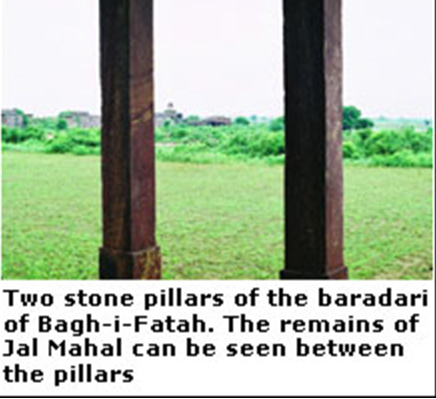

On his return from Khanwa, Babar ordered the plantation of another garden at Sikri. Some remnants of this garden are still visible. The well was constructed into a three story baoli with rahat to bring water to the surface. It can still be seen behind the Sikri ridge. The present route to it is through the Nagar village after passing Moti jheel. The site of the garden is uncertain but it is probably near the present Ajmeri Gate at Sikri. A part of the Baradari which is described in Dr Ram Nath’s book, Babar’s Jal Mahal: Studies in Islam as the Chaukundi, the four-sided shelter from the sun, has survived. Now there is a small lake there as well, which must have been a large one, for in the centre of the lake Babar had the Jal Mahal constructed. A portion of it is still present. It has an outer covered corridor and an inner octagonal building where one could sit and relax. The entire building is made up of local red stone. There must have been water in between the two buildings as they could only be reached by boat. It must have been a beautiful site to rest and enjoy.

Even today it is not that bad a picnic spot. Gulbadan Begum in Humayun Nama says that her father use to sit there and write his book (Babarnama). Dr Ram Nath has described this site in his article ‘Studies in Islam’ (1981).

Having gotten through the battle of Khanwa, Babar went through a period of respite. He lived in Agra for most of the time but never sat idle except when he was ill, of which there were many episodes during his Hindustan years. He was very aware of the lack of running water from brooks and springs, which he had become used to in Farghana and Kabul. He had always loved gardens and spent most of his life in them. He wanted to build a few here as well.

BabriGardens

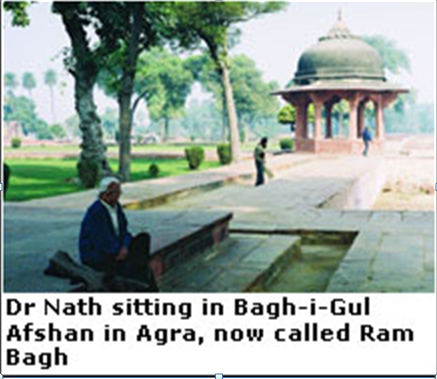

It is written in Babarnama that Babar planted and had also ordered the planning and construction of a number of gardens in and around Agra. The known gardens are Hasht Bahist, Zar (Nur) Afshan, Nilofar and Gulafshan. The last one survives partly as Ram Bagh. It was renamed by Jahangir as Aram Bagh but recent upsurges in Hindutva dropped the letter ‘a’ from the name. Ram Bagh is situated opposite the Agra water works, at the north of the AgraBypassBridge. It was a well-planned charbagh with square grass-plots with walkways in between. Running water was provided after collecting it in a large tank by rahats from the river Jamna. The water was made to fall in three levels of terraces. Its original planning is still visible, however, time and neglect have left their marks on it.

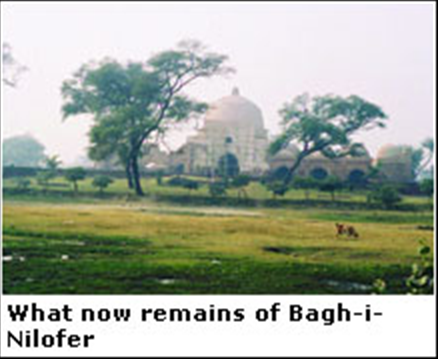

A part of Bagh Hast Bahisht survives today as Mehtab Bagh. It was planned and renamed by Shahjehan. It lies on the other bank of the river Jamna, right behind the Taj Mahal. Another remnant of history is Babar’s Nilofer garden at Dholpur. Dholpur lies 68 kilometers from Agra on the road to Gwalior, where one has to leave the main road to go towards Gor village. The octagonal hauz is still there, cut in a solid rock just as it was described by Babar.

According to the Babarnama, the year 934AH (1527/28AD) passed in conquering Chandairi. The people of Chandairi fought valiantly and Babar, for the first time, saw the traditions of ‘jauhar’ –– intention to fight until the last breath. They also sacrificed their own wives and children before the fight. While Babar was still in the area of Chandairi, he dispatched a lashkar to the east with the hope that it may control the factions of Ibrahim’s revolting Ameers. News came that his Ameers had abandoned Qannauj and were retreating. As soon as he heard this news he moved east.

Mosque at Ayodhia

According to Babarnama, heading east, Babar passed through Lucknow and travelled from there towards Awadh. He stayed at the junction of Ghaghra and Sarda rivers, 10 kilometres above Awadh — Awadh (Ayodhia) being the place where the Babri mosque, which has caused so much bloodshed in India since 1855, was situated. According to Babar in Babarnama, he never went to Awadh. He said he stayed a “few” days at the junction of the two rivers mentioned above, to control the Afghan factions. Then someone brought him the news that there was a nice place up the river where plenty of shikaar was available. He thus moved northwest.

The architecture of the Babri mosque is also not Babri. It is more akin to the Pakhtoon period. It was constructed by one of Babar’s ameers, Baqi Tashqandi, and was named after Babar, as a number of other mosques spread all over north India like Sambal, Panipat, Rohtak, Palam, Maham, Sonepat and Pilkhana were named. All were constructed during his reign but none appear to have been built on his orders.

Gwalior

Early in 935AH (1528-29AD), Babar found some time for leisure. He travelled enjoying the sights and sounds of his newly acquired country. One of Babar’s ameers captured Gwalior. Babar was interested in looking at the famous fort and visited it. His description of Gwalior is outstanding.

Gwalior is now a tourist town, approachable by road, train and air. The Fort of Gwalior lies at the centre of the city, situated high up on the mountain. It can be seen from all around as a huge fort going on for miles. It would be wise to visit it in a vehicle otherwise one will find oneself walking the entire day. The fort is walled around. Inside, the area is hilly with most of the buildings destroyed. Babar describes the northeast section of the fort, where there are palaces of Man Singh and his son Vikrama. He liked the palace of Man Singh which had four stories, all constructed of stone but with certain dingy and dark places.

Vikrama’s palace was not so well-received by him and is now crumbling down. Babar also describes in Babarnama the Urwa valley which is in the middle of the fort facing west. There he saw huge Jain statues which he did not like and ordered to be removed. These, since, have been restored. The valley is enclosed on three sides with various sized statues.

There are a number of other mandirs as well inside the fort. The most famous being ‘Sas bahu ka mandir’ (mother-in-law and daughter-in-law’s place of worship). In fact these are two mandirs, the mother-in-law’s is large and the daughter-in-law’s is smaller. The traditional rivals could not even pray at one mandir.

In the town, there is an important Sufi shrine related to Babar. Babar mentions in Babarnama, Ghaus Gwaliori, a Sufi of ‘Shattari tariqa’, who helped in the capture of the fort and also came to him to save Rahim Dad, the governor who was in revolt at the time. The shrine was built during Akbar’s days. It is a fine building with beautiful cut stone work all around. Within this compound also lies the final resting place of Tansen, Akbar’s musician.

Babar also visited a waterfall in an area south of Gwalior which he calls Jharna. We searched for it but never found it. However, while searching for the waterfall, we found another important personality. Allama Abul Fazl, the panegyric Mughal historian who lies buried about 30 kilometres south of Gwalior on the road to Jhansi.

Bihar and Bengal

Most days of 935AH were passed shadowing Babar’s ameers who were trying to subdue the Afghan factions’ spread over Bihar and Bengal. Babar by this time had become a Shahenshah. He could now afford to send out commanders deputising, like his sons and his ameers, to look after and subdue the revolts. Still he followed them to be near them and keep overall control. The Afghan factions were not giving them a stand to fight but adopted a game of hide and seek instead. Babar reached up to Maner (near present Patna) where he paid homage to a local Sufi, Shaikh Esa Muneri. Soon Bihar was taken over. At the time Bengal was under Nusrat Shah who showed interest in an agreement which was concluded after a few exchanges of embassies, accepting overall suzerainty of Babar.

He then began his journey back to Agra.

Most of Babar’s autobiography, the Babarnama, was also compiled during his Hindustan period. He even wrote it when he was returning to Agra from Bihar. At the river Ghaghar, he encountered torrential rain and storm which pulled down his tent and his papers were blown off and got drenched. He spent the entire night there saving the papers and drying them.

During this period he also wrote letters to his sons and ameers, which shows his interest in their teaching, language, spelling, grammar and responsible attitudes for ruling, behaviour and interpersonal relations.

In this period he also mentions how he ordered the distance between Agra and Kabul to be measured, post stations to be established at certain distances and the way they should be maintained financially.

September 09, 2007

=

In search of Babar

By M.H.A.Beg

Zaheeruddin Babar, the first Mughal emperor, loved a number of Central Asian places for a variety of reasons

If Zaheeruddin Mohammad Babar was still alive, he would hate to go to the country of his birth, Uzbekistan. Babar regarded the Uzbeks as foreigners to his country. According to him, they were usurpers, people from a foreign land, Dasht Qabchaq, and invaders. Shaibani Khan, their leader, came to Babar’s country at the invitation of Baisnaghar Mirza, a Taimuri descendant, after getting involved in an infighting between cousins for which the Taimuris are so infamous. This caused the exit of the Taimuris from Mavarun Nahar in 903AH (1497-1498AD).

Yet, it is this country, Uzbekistan, which has adopted Babar as one of its heroes. Before independence, when the country was under the Russian rule, it was forbidden to talk about national personalities. The fall of Russia and the independence acquired in 1991 brought a rethinking of self and non-self to the country and resulted in adopting Amir Taimur, Ali Sher Navoi, Ulgh Beg and Babar as its heroes.

In his early years, when he was a teenager, Babar did not play a significant role in Mavarun Nahar. Being a practical man he soon realized that it was difficult to get control over the existing circumstances and opted for greener pastures. His role in the area did not span more than 10 years. He ruled Farghana as well as Samarqand, the apple of his eye, twice. But those were the days of a young buccaneer and there were old hawks around. And now the people of Uzbekistan regard him as a writer, a poet and an adviser on theology, but not as a warrior or king.

Babar used to write Turki ghazals. All of this is well-documented in Uzbekistan. His well-known literary work is Babarnama, his autobiography. It has been translated into all major languages of the world. Several editions of Babarnama have appeared from places like Harvard to Kyoto. Babar had deep attachment to his home country. The way he describes its beauty in his literary work is quite remarkable. The question is, does the beauty of Uzbekistan that Babar so fondly speaks of, still remain? Can we still taste the sweet apricots of Farghana? These were the questions that were weighing on my mind when I set out to look for Babar’s country a few months ago.

Babarnama begins with the announcement of Babar becoming the Badshah at the age of 11. He does not declare where he was born. We know that his father had a castle in Akhsi which is on the north bank of the Syr Darya. What made him the Badshah was an accident. In the book, Umar Shaikh Mirza, his father, walks up to his pigeon house which overlooks a deep ravine and is flying pigeons when the Kabootar Khana gives way and down comes the house, and with it Mirza. And as Babar mentions, he becomes a ‘falcon’. Interesting, isn’t’ it?

Now let’s talk about a few famous places.

AKHSI: Babar’s father’s capital disappears in the book, and we do not know the cause of this disappearance. These days, it is a mound known as Akhsikint. You can still see the bricks and remnants of his castle. It is still on the north bank of the Syr being divided by a road constructed to lead to the bridge on the river. Walking on the mound you can pick up pieces of pottery and bricks. Annette Beveridge, the best known commentator on Babar, has mentioned the erosion by river as the cause of destruction of Akhsi. There is no sign of any erosion at present. Akhsikint still stands on the north bank of the Syr.

KASHAN: Following the Kashan River backwards leads to the town of Kashan praised by Babar for its beauty. It is a town 45kms north of the main road. The town is now known as Kasansoy. The road runs parallel to the river and Babar calls this river in his book the Kashan Water. It is a small river. Not many gardens described by Babar as Posteen Pesh Bara (the beautiful front of a coat) are left. The countryside is still green though. It is a fine clean town with many Chaikhanas overlooking the river. There is a 16th century mosque which is not open to the public.

ANDIJAN: At the time of his father’s death, Babar was in Andijan, the biggest town in the Farghana Valley. As he was young and there was the fear that his uncles may overrun him, he was taken to the Namazgah before proceeding to the mountains to escape. It is surprising that in his book he uses the word Namazgah and not Masjid or Maschit as Turkish people call it. Travelling in the length and breadth of the country solves this problem. In this part of the world there are three types of prayer places, a Namazgah for everyday prayers, a Jama Masjid for the Juma prayers and an Eidgah for festive prayers.

According to Babar, the Andijanis are all Turks. This is true. There are a lot of honest, simple and religious Turkish people here who would greet you with a Salam, with their right hand on their hearts, bowing their heads a little.

Babar also praises the good looks of the Andijanis, their fair colour, and symmetrical and proportional features. He speaks highly of Khawaja Yusuf Andijani for his music. He was a musician and singer of Baisnaghar Mirza’s court. He had deep penetrating voice. Fruits are still in abundance in Andijan. Grapes, melons, pomegranates and apricots are found in good quantity here. In Babar’s times, melons were found in great numbers, so much so, that they were never sold on farms. Anybody could pick them. The abundance resulted in ignoring the product.

It is said that the fort of Andijan used to be the third biggest after Samarqand and Kesh’s forts, but was destroyed in an earthquake. In fact, nothing of the old town is left. The site of Babar’s house has been rebuilt. There is a courtyard in the middle with a fountain and statue of Babar in the centre. A garden called Bagh-i-Babar has been developed southeast of Andijan on a two-acre site on three levels. A small building containing paintings as perceived in Babarnama and cupboards and shelves with books on Babar can be seen all around.

In his book, Babar also praises the ‘Shikhar’ available in and around Andijan. He thinks pheasants are really fat, and four persons cannot eat one cooked pheasant. Pheasants are still seen occasionally here, but most of them are now found in museums. Farghana is one of the regions of Uzbekistan where the rekindling of Islam can be observed. In Andijan, the biggest 16th century mosque has been closed down. The other mosque is a small one. I had the chance to offer my Friday prayers there. The mosque was full with people and its courtyard was crowded. Most of the ‘Namazis’ were young men.

THE FARGHANA VALLEY: During the 1917 communist uprising in Russia, followed by the division of the country on ethnic grounds, the people living in the Farghana Valley were Turks, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrghyz and Mughals, but the valley was carved up into Uzbek, Kyrghyz and Tajik areas. These artificial divisions created more problems than before. Thus, there is a significant number of community problems in all three countries in all spheres of life, and minorities continue to suffer. Dividing Muslims was a political necessity and was done to prevent unity in the region. This carving has resulted in the valley to be divided into three countries. This caused the natural road, railway and waterways of the Farghana valley to be separated from the main land mass. The main passage being blocked, a new road had to be built over the 2,267-metre-long Kemchik Pass.

OOSH: In his book, Babar describes the beauty of Oosh, and the road leading to it, in resplendent words. Oosh is now in Kyrghyzistan. You have to have a visa, and pass through the customs counter to enter the city. No doubt, Oosh is a small, beautiful town with a river (Babar calls it Andijan Rud) now named Ak Bura which passes through the middle of the town. The river flows towards Andijan. Most of the land on the two sides of the road comprises cotton fields. Women and children work in the fields. There are no gardens here that Babar writes about in his book. Babar describes Oosh as four Yagash from Andjian. What Yagash means, no one knows. Khan-i-Khana Abdur Rahim Khan in his translation of Babarnama translated Yagash into Farsang. Farsang is still used in Iran and it is equivalent to the length of 6kms.

In the south-west of the old town is a mountain called Barakoh. Babar’s uncle Sultan Mahmud Khan had made a ‘Hujra’ on the top of this mountain. Babar, in 1496AD, constructed a ‘Baradari’ here. I went around the mountain, but found no sign of those buildings. A new building has been built up on the south-east edge of the mountain and is called Takht Sulaiman, and on the Takht there is a prayer place as well. According to tourists’ guide, this place is somehow connected with Babar’s Baradari. This cannot be right as Babar says in his book that his uncle’s Hujra was on the top of Barakoh and his own Baradari was a bit lower.

According to local books, Hujra was destroyed in the 17th or 18th century. Nobody knows why or by whom and the Takht Sulaiman mosque was not built until 1829. The mosque existed until 1963 and destroyed again by the communist administration and was rebuilt in 1989.

MARGHINAN: It is now called Marghilan. It is 72kms south-west of Andijan. Here pomegranates and apricots are found aplenty. One variety of pomegranate has extra large seed, called ‘Kalan Dana’ and a special apricot the seed of which is replaced by almond called ‘Subhani’.

KHUJAND: The only border open to Khujand, Tajikistan is Oyibek, which is about 100kms south-east of Tashqand. It takes about two hours to get clearance of the two customs and immigration check points. This is followed by the 62kms of inhospitable, barren and hilly land of Tajikistan until you reach the Munughal mountain which has to be circumnavigated to enter the valley right on the Syr Darya. The valley is as beautiful as Uzbek Farghana. The river can be crossed by two bridges to reach Khujand.

In 1498AD, Babar was stationed at Khujand for a year. He found it to be very limited in resources and was unhappy here. He loved all the fruits of Khujand, particularly pomegranates.

KUND-I-BADAM: Another town in the Farghana Valley is Kund-i-Badam which Babar has praised in his book for its almonds. It is now known as Kunbadam. It is 80kms east of Khujand. Its main road is clear except a few broken patches. There are gardens on both sides of the road where apricots, apples, almonds, pomegranates and mulberry trees can be seen. To the left side of the road is Tajikistan and to the right is Kyrghyzistan.

The town of Kund-i-Badam is relatively new, as the old one was destroyed in an earthquake. There are two madressahs left from the old town, one a madressah for girls called Aaim, and one for boys, Mir Rajab Khan Dotha. The boys madressah has a courtyard and a well in the middle, with rooms all around.

ASFARA: It is the only other town left, described by Babar as the Arghana Valley. It is 30kms south-east of Kund-i-Badam. As soon as you come out of Kund-i-Badam, there are hills, as mentioned by Babar, on both sides of the road. The road is narrow and passes over a small hilly pass to enter into Asfara. There are factories on both sides of the rod. Most of them are now closed and a lot of people are jobless. In the centre of town is a river also called Asfara and on both of its banks are teahouses. Asfara is famous for its pullao. It is said that nowhere else in Tajikistan you can get such tasty pullao. It is made of rice which is small in size and a bit broad in the middle and reddish in tinge.

Babar in his book also talks about a rock two miles south of the town, a rock which reflects like a mirror, Aaina that nobody knows about.

In Babar’s footsteps

May 14, 2006

ARTICLE: In Babar’s footsteps

M.H.A. Beg visits Central Asia to follow Babar’s passage from Amu Darya to Nilab (Sindh)

In the year 1504 after spending one year in the mountains of Farghana, where he could not make any headway, when relations and friends had all turned against him, the 22-year-old Babar took a bold decision. His book, Babarnama, gives all the details about his decision to leave his homeland in search of another kingdom.

Babar’s first intention was to go to Khurasan. His uncle, Sultan Husain Mirza, ruled Herat. So in Muharram of that year he camped in the green pasture around Hisar (near Doshanbay, Tajikistan). He was poor and destitute. He has described in Babarnama how he had “more than 200 and less than 300 followers.” Most of them were on foot — they had no arms except for wooden staves. They wore loose slippers and were meagrely clad. Babar himself had only two tents which he shared with his family. At every camp he would sit under a hastily made “Chappar”.

But his luck was going to change soon. He was in the area ruled by Khusro Shah, known as a cruel and unfair ruler of Hisar, Qunduz and Afghan Turkistan. People would approach Babar and bring him stories that they were sick and tired of the Shah’s rule. It was their way of submitting to him. Khusro Shah used to be an ameer to Babar’s uncle Sultan Mahmud Mirza of Samarqand, who had gained strength at the expense of Babar’s cousins, killing one of them and blinding the other. The third cousin, Mirza Khan, had accompanied Babar to Hisar. From Hisar they took the road to Termiz (Uzbekistan) which was governed by Baqi, the younger brother of Khusro Shah. Baqi was clever. He realised the precarious state of affairs of his brother and tried negotiating between the two sides.

Amu Darya

Babar must have crossed the river Amu somewhere near Termiz. This is the famous crossing site of men and armies. The most famous in recent history being the Russian army of 1979 through the Bridge of Friendship, named in contrast to the act of invasion.

The bridge still stands. It is used by the trade traffic. Not only does it have a road but also a railway crossing from Uzbekistan to Afghanistan. To establish a station for unloading goods, they built a town named Hayratan, a dismal place with a railway yard and some houses belonging to the railway workers and army personnel. The town is so recent that it doesn’t even show on some of the older maps of Afghanistan. These days you cannot go on the bridge directly, but a guard will direct you to a place from where the bridge and Amu Darya are within sight.

The bridge is a steel construction, painted pale yellow on the top. Amu is a big river in the region, made famous in Arabic historical writings as the “Nehar”. Arab historians have given the area beyond a name so beautiful and descriptive, “Mavara-un-nehar”. The railway does not go beyond Hayratan. This is the only part of Afghanistan where there is a railway built by the invading Russians. It is their legacy.

Babar writes in his book that after crossing the Amu on a raft, he landed in Afghan Turkistan where he was greeted by vast flat grasslands.

The country is an open field, much warmer than the mountainous Afghanistan of the centre and the south. The land on the banks of the river was good for cultivation. The eastern part with open grass lands is horse country where horse raising is still practised.

As soon as Babar arrived here and the ameers of Khusro Shah started gathering around him, Babar decided to switch directions from Khurasan to Bamiyan. Another reason for this change was to leave behind his family in the mountainous castle “Ajar” for safe keeping.

Aibak

Two ameers of Khusro Shah who joined Babar have been particularly mentioned by him in Babarnama. Qambar Ali Sallakh and Yar Ali Bilal brought him strength. Yar Ali Bilal joined Babar at Aibak.

Aibak is a dusty town of Turkistan, which also boasts of a Buddhist stupa. Yar Ali’s joining Babar was not only a boost to his strength but the relation he established here proved to be historical and long lasting.

Yar Ali Bilal was the grandfather of Bairam Khan, of Akbar fame. The friendship between the two families here, as the ruler and the instrument to rule, lasted for seven generations, the last of which was known historically in the days of Aurangzeb when Muhammad Munim a descendent was still working as governor of Ahmad Nagar.

Babar remembers in his book that there was not a single day when people who were against Khusro Shah didn’t come to join him. On learning these facts Khusro Shah was disgusted. Another turn of luck occurred through the intervention of kind of bully of the period, Shaibani Khan. Khusro Shah was based at Qunduz, which he strengthened to save from Shaibani. For 20 years, he collected arms and provisions to save the castle of Qunduz from him. As soon as Shaibani took Farghana and showed his intention to come to Qunduz, Khusro Shah was worried. He could not stay in Qunduz, so he moved out towards Kabul. It was better to surrender to Babar than get slaughtered by Shaibani. There is a saying still frequently quoted in Afghanistan, “Afghans’ anger and Uzbeks’ kindness are equivalent”, and how true this is historically.

Qunduz

Qunduz today has a big army camp, which at present is occupied by American forces. The Americans here travel in convoys of big wheeled, gun transporters at a speed of around 50 kilometres per hour — they do not allow anyone to overtake them.

We followed them on the road to Qunduz for about 50 kilometres until they stopped near a mountain side and jumping out of their vehicles, stood on attention with their guns to let all the traffic at the back pass by. The American presence cannot only be felt on the roads, it is also there in the hearts and minds of the people. They publish a monthly newspaper Sada-i-Azadi, in Dari, Pushto and English languages, which is full of propaganda, singing praises of the good work that the Americans are doing.

We were able to see the mud castle of Khusro Shah. The place is unsafe as it is full of mines. A shepherd asked us to follow only the track made by sheep. With just the base and a few walls standing, the place is in a bad state.

Back to history and Babarnama. Khusro Shah sent his son-in-law Yakoob to Babar. Already present there was Khusro’s younger brother Baqi. Both Baqi and Yaqoob helped Khusro save his neck. A treaty was arranged for the surrender. Babar followed the direction in which the water flowed on the Surkhab and camped at the junction of the Andrab and Surkhab rivers. This is a delightful little town in Doshi with a small bazar with many “Chaikhanas” selling Qabli pullao and kebab. People laze around here even now.

Andrab is the bigger of the two rivers. Its clear water flows down from the east side of the mountains. Surkhab in contrast is smaller with muddy water flowing from the west. Andrab’s clear water and Surkhab’s reddish muddy water join at Doshi to form a bigger river which flows towards Qunduz to ultimately join Amu.

Doshi

Babar describes the meeting and the surrender in his book:

“The next day, I crossed the Andrab and sat down under a big Chinar tree.”

Chinars are big, bushy trees with leaves as big as the palm of a hand. The leaves also have five corners just like our fingers. Many of the old Chinar trees of the area are still very much around.

From the other side came Khusro Shah with his entourage. The surrender ceremony took hours with Khusro Shah kneeling incessantly to Babar and all his ameers. Babar’s change of luck and good fortune came with this surrender and without a fight. He thanks his God:

“It is He who gives kingship or takes it away.”

This was a remarkable event in Babar’s life, when he left his destitute past and gained strength every day, never looking back. The best part was that no fighting took place. He won it all by shear politicking and good luck.

At this time Babar observed the Sohail (Canopus), the brightest star in the southern constellation. This star is known for its good luck. Babar’s companion Baqi immediately quoted a Persian couplet meaning “To see it is the sign of luck and wealth.”

Generosity

Babar kept his treaty to the word. He could have taken anything he wanted from the rich Khusro Shah but he would not do such a thing. Mirza Haider of Tarikh-i-Rashidi writes:

“Khusro Shah tried giving many presents to Babar. Though Babar at the time had only one horse, which was also being used by his mother, he did not confiscate anything from Khusro Shah. He allowed him to take away anything he wanted, before he was given leave to go to Khurasan.”

Babar’s movement until now had been from Amu to Aibak and from there to Ajar and Kahmard where he left his family and then moved eastwards to Doshi to accept the surrender.

It was now time to ponder over what to do next, and where the next movement should be. Kabul was not far away and Babar had a sort of claim on Kabul as it used to be ruled by his uncle Oolugh Beg. Oolugh Beg’s son had recently been disposed of by his father’s courtier. Babar must have decided for it then. He moved to Gowrband.

Gowrband lies on the south of Hindukush. A lofty mountain range, it is so named as the Indians migrating here were not used to such snow covered peaks and passes and many were killed. Babar does not mention the pass he used but the time of the year was summer. Later while describing the country around Kabul, he writes, “There are seven passes in these mountains,” all of which must have been open in summer. The most frequently used one now is the Salang Pass build by the Russians.

We passed through it. It is 3,363 metres high and 2.7 kilometres long, and here it was even snowing in March. The mountains were covered with snow, the view was fantastic, and the road would not be open but for the tunnels and shoulders developed and the men and machines working to keep this road open. This was started in 1958 and was completed in 1964.

The next stage in the passage was Qarah Bagh, a small town about 35km north of Kabul.

At Qarah Bagh, Babar says that he sat down with his courtiers to decide whether to go for Kabul, which was ultimately decided. At that time Kabul was ruled by Muqim Arghun. Arghuns were distantly related to Taimuris, but Babar’s claim on Kabul was due to close relation with Oolugh Beg, his uncle who had ruled Kabul until two years ago. Muqim had taken over from Oolugh Beg’s young son Abdur Razzaq Mirza. His claim on Kabul was more than that of the Arghuns, he must have thought.

On hearing of the approach of Babar, Muqim played on time. He sent information to his elder brother Shah Beg in Qandhar to get help and advice. Muqim soon realised that he was not going to get any help and decided to surrender to Babar. This second surrender without fight was another feather in Babar’s cap. This was a combination of politics and show of military strength as Babar’s forces came surrounded the castle at Kabul. A treaty was established and Kabul was left to Babar. Again history was repeated with Muqim being allowed to take whatever he could.

Kabul

Babar writes in his book:

“Kabul is a strong fortress, the enemy cannot invade easily. It has grasslands, rivers, flowing water and above all mountains all around. It is the centre of trade from the north as well as Hindustan. It has excellent weather and lots of fruit trees.

What is left of Kabul now is the barren dry mountains devoid of any trees or greenery. Even the river Kabul is no more than a big drain now. Over the years, this place has been inhabited by many people who spoke a number of languages. Babar, when he arrived here, had never come across a city where so many languages were spoken.

Babar lived in Kabul for 21 years. As usual he describes the city and the country, its roads, its passes, its birds, its animals, trees, flowers, etc. No king has ever written about Kabul as much as him. He loved the city and the country. He built gardens there, adding to the already present ones built by his uncle Oolugh Beg. In all Babar built 10 gardens in the country. Unfortunately none of these are left now. They have been destroyed by the incessant war going on since 1979 when the Russians invaded the country. The one that is left is also the one in which he himself lies buried. It is called Bagh-i-Babar, though there is not much of the bagh left there.

Bagh-i-Babar

This place is a walled enclosure with no grass and no evidence of Charbagh. There is no running water and no fountains. The only tree left is the dried stem of an old Chinar, which stands by the pavilion.

The present government is taking an interest in this bagh. The Aga Khan Trust has appointed a Hindustani architect to rebuild it. Still, the terraces are being laid out and fresh saplings planted. A wall has been constructed around the graves of Babar and his relatives who lie buried there. Fortunately the headstone placed by Jahangir has survived but the grave will have to be rebuilt. The small marble mosque, which was originally built by Shah Jahan has been rebuilt. The architect told me that before the work began the whole ground was to be cleared of mines.

While searching for the mines they were able to find pieces of marble that was enough to cover the mosque all over. Though the built up is shoddy and patchy. The talao (swimmimg pool) is being renovated too. The worst site in the complex is the pavilion built by Abdur Rahman in the 1880’s. Though he did order renovation, the pavilion is placed at a site that hides the mosque and burial site. It is now a modern building that does not match the period it represents. Still, one hopes that the garden will bloom again.

Ziarats

Babar has described three Ziarats in Kabul, which were places of pilgrimage in his days. All three are in poor state and need looking after. The best known is Chashma Khawaja Kizr. It is on the other side of Babar Mountain. There is a spring here too along with a place to sit and contemplate. Babar describes a Qadamgah as well but it is not there now. The second Ziarat is another spring, which Babar describes as the burial place of a “Khwaja Shammu”, which according to other sources is Khwaja Shamsuddin Janbaz though there is no certainity about it. Raverty calls him Jahan Baz and local Kabul Professor Abdul Hai Habibi calls him Khawaja Hammu. The present local tourist books call this site the Ziarat Asheqan-o-Arefan.

The third Ziarat is another spring known as Khawaja Roshnai, quiet high up in the mountain in old Kabul, needing much care.

Takht-i-Babar

What Babar does not describe in Babarnama is his takht, which he got carved by the mountain side and a basin also in the stone where he used to sit and drink. His great-grandson Jahangir visited Kabul in 1607 and saw the takht which has an inscription dated 914AH (1508-9AD). Jahangir himself had another throne and basin built and had his name engraved on it too. Before the war started this throne was found by Abdul Hai Habibi and Nancy Dupree lying behind the Ibn Sina Hospital on the right bank of the river Kabul. Apparently it had fallen down from the mountain.

Babar has also described the Shikargah in Kabul where they used to catch birds. We were taken to a lake, Kole Hashmat Khan, situated between two mountains, which could be what is described in Waqa-i-at as Aab-i-Baran, where I was told birds still flock though we never saw one in March.

Estalef

Babar also mentions Estalef and Estagrech as local beauty spots. Both these places are still there. We visited Estalef, which is 40km northwest of Kabul. It is a small hill station. The road leading to it is unmetalled. The whole area is more like a garden. At the hillside there is a flat area high up underneath which flows a small brook. The area has many Chinar trees. Babar used to sit under the snow capped mountains and enjoy the local scenery here. The town and the area were unfortunately destroyed by the English revenge Army which was sent after the killing of Alexander Burns in 1842 under leadership of General McCaskel.

Bagh-i-Wafa

The most beautiful of Babar’s gardens was in the Nangarhar province near Adinapur. Adinapur was the capital of Nangnahar province before Jalalabad. Adinapur is unidentifiable but the description of the way to Bagh-i-Wafa, given by Babar could be followed. We followed the main Jalalabad-Kabul road. About 30km off the main unmetalled road, a rough ride takes you from Surkhrud (river) to Balabagh.

The site Babar describes can be made out from the remnants of a mud castle . The area is now famous for growing citrus fruit. There were so many Narang (Chakootra) trees here that the area has a sweet and sour smell.

The Afghans

One of the honours which should also be bestowed upon Babar is the fact that when he reached Kabul he was the first in history to have gone into the details of Afghan tribes. The Afghans were mentioned earlier by Alberuni during the days of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi as inhibiting from Kabul to Sindh, but there was nothing more about them anywhere. Babar is the one who has given the names of the tribes and also written about there habitats and movements. Olaf Caroe has realised this and he pays tribute to Babar for it in his book, Pathans.

The Tropics

The power of observation that Babar possessed was extremely strong. Another excellent description he gives of this part of the world is the change of scenery that he experienced before reaching Adinapur. He also notices the sudden change from temperate to tropics here. The trees become more bushy, and greener, the environment is different as the weather changes. He even noticed the change of habits in people, and animals according to their surrounding.

During his 21-year stay in Kabul Babar was never idle. He was unhappy financially and mentions that taxes were difficult to collect and could only be obtained by the force of the sword.

The taxes were also not quite enough for him and his people. The year he came to Kabul, he realised this and crossed over the Khyber wandering into Kohat, Bannu, Dasht and reaching upto Sakhi Sarwar. This was a wasteful journey in an unknown, difficult to travel, dry and mostly barren land.

The next important journey he took was in 1519AD when he went to Bajaur and crossed Nilab, the ghat(river crossing) of Sindh for the first time. This time he went up to Bhira, which at the time was at the border of Hindustan. I have already described this journey in a separate article (Books & Authors, June 20, 2004). The last and final crossing of Nilab was in 1525AD when Babar left Kabul for good to take over Hindustan.

Babar: The avid adventurer

Reviewed by Dr Muhammad Reza Kazimi

Babar, although he composed memorable poetry in Persian, was concerned with preserving both his faith and his language.

THE prince of a small principality called Farghana, Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babar succeeded his father at the tender age of 12 but was soon besieged by his uncles. But when he died, it was as the founder of the glorious Mughal Empire. The details of his life by any other pen would also have held great interest, yet posterity has reason to be very grateful that Babar wrote an autobiography. One of the very few monarchs who could wield the pen and the sword with equal facility, Babar wrote his Waqa-i-Babar in his native Turki in spite of being fluent in Persian.

As a soldier, scholar, poet and emperor, Babar has excited the fascination of readers and scholars across the world. His autobiography is praised for its candour, and rightly so, but it is not his candour alone which holds the reader spellbound. Babar’s great grandson also wrote his memoirs which are equally candid; Jehangir shared his ancestor’s eye for detail and love for nature.

Babar had the observation of a connoisseur, but for all these merits his life as an emperor is not attractive as his career as a warrior. Waqa-i-Babar, Toozk-i-Babari, or Babarnama as the autobiography is variously known, has been translated and annotated by Khan-i-Khanan in Persian and by Annette Beveridge and Wheeler Thackson in English. The Humayunnama by Gulbadan Begum and Tarikh Rashidi by Mirza Haider Dughlat are supporting works by contemporary relatives. The contents of Waqa-i-Babar have been told and retold thus it is not necessary to review the text. What need to be reviewed are the notes supplied by the editor, Hasan Beg.

Besides, presenting an authentic text is an adventure on its own especially because the native Turki of Babar has undergone much travail. In Turkey (Asia Minor) it began to be written in the Latin script, and in Turkistan (Central Asia) it came to be written in the Cyrillic script. This made the task of reconstructing the original text quite difficult. In fact, it has created a controversy over how the name Babar is to be spelt or pronounced.

The Waqa-i-Babar has proven to be a popular text and has been copied by many scribes. With the proliferation of texts, errors also multiplied and a critical text of the Waqa-i-Babar became the first pre-requisite for scholars. The British Library houses 10 manuscripts and from these Hasan Beg fixed on the manuscript calligraphed by Musvi Ali Khan. Hasan Beg mentions a critical edition prepared by I.G. Manu of the Kyoto University of Japan, which was prepared with the help of three Turki and one Farsi manuscripts. The text based mainly on the manuscript of Musvi Ali Khan, was translated into Urdu by Professor Younus Jafri of the DelhiCollege in 2004. The annotation is by Hasan Beg.

We must understand Hasan Beg’s quest for an authentic manuscript in the light of the fact that no holograph of the Waqa-i-Babar exists. Hasan Beg surmises that the holograph may have been lost in the tornado of 935 AH, which Babar himself describes. This is not likely; for when Babar was describing the tornado, he would have described the loss of his manuscript as well. Later, he surmises that it may have been lost during the arduous journey undertaken by Humayun. This is the only possibility, for it provides for the opportunity to have copies of the Waqa-i-Babar made by Babar’s son and a Persian translation ordered by Babar’s grandson.

The change of script, that is Latin for Turkish and Cyrillic for Turki, has indeed resulted in confusion as is evident from the variants of Babar’s name. William Erksine translated the Waqa-i-Babar or Babarnama in 1826, and he spelt the emperor’s name as Babar. So did Annette Beveridge in her earlier writings including the facsimile of the Turki manuscript, but when she published her translation in 1912-1921 she spelt the name as Babur. The Russian historians, namely Kohr and Smirnov, were attuned to the Cyrillic script so they preferred Babar. In French, Pavet de Courteille spelt the name as Babir. My teacher Professor Najeeb Ashraf Nadvi in an article published in the Ma’arif (Azamgarh 1822) preferred Babur, but also admitted that rhymes in Persian poetry may change.

Hasan Beg himself prefers Babar, mostly on the ground of facility of pronunciation.

In this background we can understand his lament over the corruption of the Turkish script. He says that even Urdu’s debt to Turki has not been acknowledged. He lists common words of Urdu like Apa, Baji, Begum, Khan and Khanam which are all taken from Turki. Babar, although he composed memorable poetry in Persian, was concerned with preserving both his faith and his language. For his son Kamran he composed the imperatives of the Hanafi fiqh in Turki verse. The Manawi Mubeen composed by Babar has been translated into Urdu and should be available in print by the end of the year under the auspices of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Among the appendices included by Hasan Beg is a remarkable one on the ailments suffered by Babar. From the symptoms described by Babar, Hasan Beg has been able to hypothecate a diagnosis. He states that Babar suffered from tuberculosis and the dreaded disease had travelled to his abdomen during the terminal stage. Medical histories are as useful to understanding behaviour as are temperaments reflected in literary output.

Another appendix relates to influence of mystics on the Mughals. Hasan Beg shows how Khwaja Ahrar Naqshbandi was able to avert a war between Babar’s father and his uncles, but as far as the spiritual influence of his progeny is concerned, it comes through as uninspiring. The last entry of the Waqa-i-Babar relates to August 25, 1530 AD, according to which he forgave the rebel Rahim Dad at the instance of Shaikh Muhammad Ghous of Gwalior. The last phase, regarding Babar sacrificing his life for his son Humayun, is carried in a purported addendum. However, Stanley Lane Poole refuses to ascribe it to Babar on the ground that it is not found in the editions of Teufil or Pavet de Courteille, as well as based on stylistic considerations,. This scene is nonetheless graphically recorded by Abdul Fazl and carries full conviction.

In conclusion, one would like to cite the tribute paid by Babar’s English translator Annette Beveridge: ‘His autobiography is to be counted among those invaluable writings which have been praised in every age. It shall be apt if they are put in the same class as the confessions of St Augustine and Rousseau, the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton. Its like is not to be found in Asia.’ Ms Beveridge leaves out only one detail: none of the other authors mentioned by her include an empire builder like Babar.

________________________________________

Waqa-i-Babar By Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babar Indus Publications, Karachi ISBN 978-0-9554383-0-1 396pp. Rs1500