Bhutan: Foreign policy

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

How policy (including foreign policy) is made in Bhutan

A fledgling democracy’s flaws shouldn’t hit ties

Tandi Dorji

The Times of India 2013/07/12

In a democracy, consultation and consensus are needed on issues. This is provided for in the Constitution [of Bhutan], which says that other than the Cabinet, institutions have a role in policy (particularly in international relations).

Article 20(3) says, “… (Cabinet) shall aid and advise the (King) in the exercise of his functions including international affairs, provided that the (King) may require the (Cabinet) to reconsider such advice, either generally or otherwise.” And Article 20(7) says, “The (Cabinet) shall be collectively responsible to the (King) and Parliament.” Such provisions limit the Cabinet’s authority to take decisions unilaterally.

The Constitution outlines steps for appointing a secretary or head of a district administration, Bill-passing procedures, taxation, etc, combining the need for checks and balance with the procedures culminating in assent by the king. Bhutan decided decades ago to place India as the cornerstone of its foreign policy and combined this with a commitment to refrain from diplomatic ties with the UN Security Council P5. Bhutan wanted stability and predictability in its relations with the world.

It wanted partnership with India as it brought rapid socio-economic growth, political strength and maturity among its people. Bhutan’s foreign policy was the foundation for her development.

How was it that an individual PM, without due process, so easily altered the roots of foreign policy? Is it possible that the Constitution limits the powers of government in appointing heads of district administrations but grants powers to determine issues affecting national security?

2008: The Cabinet’s supremacy is established

The failing can be attributed to the odd start we had to our democracy in 2008, where the new elected Cabinet was dominated by former Cabinet ministers in the King’s council. The system changed, but people remained the same. With the same people in power (now with greater power), institutions (bureaucracy, judiciary, constitutional bodies) were inhibited in establishing a new democratic system of working. Had less overbearing individuals been in the 2008 Cabinet, procedures would have evolved for decision making, implementation and accountability. Instead, the Cabinet’s supremacy saw institutions lose autonomy.

India’s fault: dealing with individuals with limited tenures

It also falls on the India which neglected its long-time counterparts in the bureaucracy, army and civil society, choosing to deal with individuals with limited tenures and mollify them. India must wait as we address the fundamental failing in our new democracy.

As long as Bhutanese foreign policy is determined, not by individuals, but by an established system of checks, balances and consultations, there’ll be little room for politicization by any side or country.

Tandi Dorji is founding member of Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) Party

Bhutan-India relations: the 1960s onwards

Suhasini Haidar | The crossroads at the Doklam plateau | JULY 26, 2017 | The Hindu suhasini.h@thehindu.co.in

There are many strings that tie Bhutan to India in a special and unique relationship, but none are as strong as the ones laid down on the ground: 1,500 km, to be precise, of roads that have been built by India across the Himalayan kingdom’s most difficult mountains and passes.

Since 1960, when Bhutan’s King Jigme Wangchuk (the present King’s grandfather) entrusted the then Prime Minister, Jigme Dorji, with modernising the country, that had previously stayed closed to the world, those roads built and maintained by the Indian Border Roads Organisation (BRO) under Project Dantak have brought the countries together for more than one reason.

A one-way street?

“All the new roads [they] proposed to construct were being aligned to run southwards towards India from the main centres of Bhutan. Not a single road was planned to be constructed to the Tibetan (Chinese) border,” recounted one of independent India’s pioneers in forging ties with Bhutan, Nari Rustomji, a bureaucrat who also served as the Dewan, or Prime Minister, of Sikkim from 1954 to 1959, in his book Dragon Kingdom in Crisis . When the Chinese presented a fork in the road, Rustomji said, “with feelers to bring Bhutan within the orbit of their influence”, Bhutan stood firm in “maintaining an independent stand”.

Just a few years later, during the India-China war of 1962, Bhutan showed its sympathies definitely lay with India, but it still wouldn’t bargain on that independent stand: when Indian soldiers retreated from battle lines in Arunachal Pradesh, they were given safe passage through eastern Bhutan, but on the condition that soldiers would deposit their rifles at the Trashigang Dzong armoury, and travel through Bhutan to India unarmed. (The rifles lie there till today.)

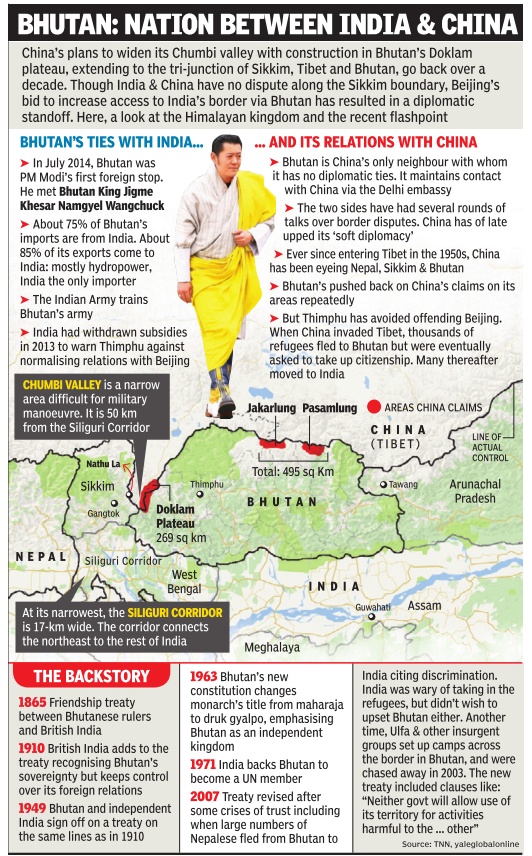

Bhutanese- Chinese discussions about Doklam

The Doklam plateau is an area that China and Bhutan have long discussed, over 24 rounds of negotiations that began in 1984. In the early 1990s China is understood to have made Bhutan an offer that seemed attractive to the government in Thimphu: a “package deal” under which the Chinese agreed to renounce their claim over the 495-sq.-km disputed land in the Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys to the north, in exchange for a smaller tract of disputed land measuring 269 sq. km, the Doklam plateau. Several interlocutors have confirmed that the offer was repeated by China at every round, something Bhutan’s King and government would relay to India as well. While India was able to convince Bhutan to defer a decision, things did change after India and Bhutan renegotiated their friendship treaty in 2007, and post-2008, when Bhutan’s first elected Prime Minister Jigme Thinley began to look for a more independent foreign policy stance. Some time during this period, the PLA is understood to have built the dirt track at Doklam that is at the centre of the current stand-off, including the “turning point”, and the Bhutanese army appears not to have objected to it then.

During the next five years of his tenure, Mr. Thinley conducted more rounds of talks, including on the ‘Doklam package’, and even held a controversial meeting with Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao (in Rio de Janeiro, 2012), suggesting that Bhutan was thinking of establishing consular relations with China, much to India’s chagrin. During this time, Bhutan also increased the number of countries with which it had diplomatic relations from 22 to 53, and even ran an unsuccessful campaign for a non-permanent seat at the UN Security Council.

By 2013, India took matters in hand, and the Manmohan Singh government’s decision to withdraw energy subsidies to Bhutan on the eve of its general elections that summer contributed to Jigme Thinley’s shock defeat. When the new Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay’s government prepared his first round of boundary talks with Beijing a few months later, New Delhi took no chances. It dispatched both National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon and Foreign Secretary Sujatha Singh to Thimphu to brief him. China, it would seem, realised it could no longer press the Doklam point, and a year later even offered India the Nathu La pass route through Sikkim for Kailash-Mansarovar yatris.

With the latest stand-off, that includes the cancellation of the Nathu La route, China appears to be back in the eastern great game that Bhutan has become, or an “egg between two rocks”, as a senior Bhutanese commentator described it. India must also consider that the PLA road construction that brought Indian troops to Bhutanese territory may be what is known as a “forcing move” in chess. By triggering a situation where Indian soldiers occupy land that isn’t India’s for a prolonged period, Beijing may have actually planned to show up India’s intentions in an unfavourable light to the people of Bhutan.

Bhutan is also the only country in the region that joined India in its boycott of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s marquee project, the Belt and Road Initiative. In China’s thinking, any reconsideration of Bhutan’s unique ties with India, forged all those decades ago in asphalt and concrete, would be not only a prize, but possible payback.

Bhutan-India relations: 2012-13

Ex-PM’s Global Moves Left New Delhi Cold

Keshav Pradhan | TNN

The Times of India 2013/07/12

Bhutan’s relations with the UN Big Five

New Delhi is understood to be upset (in 2012-13) with the manner Bhutan under Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT) allegedly overlooked India’s basic national interests in the past five years.

Bhutan’s stated policy is that it won’t allow the UN Big Five to have diplomatic missions in Thimphu. But, New Delhi believes, Bhutan circumvented this by appointing a Briton to act as UK’s honorary consul in its capital and subsequently gave him Bhutanese citizenship. This, many felt, is not in alignment with Bhutan’s stated policy. So far, the kingdom, acknowledged as India’s staunchest ally worldwide, had refrained from taking any such step in deference to Delhi’s security concerns.

Meeting with Chinese premier: 2012

Ex-PM Jigmi Y Thinley’s critics in Bhutan and India claimed that the first strain in bilateral ties appeared over the way he described his meeting with then Chinese premier Wen Jiabao in 2012. They alleged that although the meeting was “pre-arranged”, Thimphu projected it as “an impromptu interaction”. They were of the view that such “distortion” of facts made New Delhi suspicious of Thimphu’s intentions.

India, Thinley’s detractors claimed, did not take kindly to the alleged use of Chinese experts to instal heavy machinery in Bhutan. For China, they said, investing in a small country like Bhutan is a pittance.

Amid reports of friction in India-Bhutan friendship, New Delhi [in June 2103] cut cooking gas and kerosene subsidies for Bhutan. This not only became an election issue but also spread fear among the Bhutanese that India would punish their country because of diplomatic reasons.

The opposition People's Democratic Party (PDP) defeated the then-ruling Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT) in the 2013 elections. On August 1 India restored subsidized gas supply to Bhutan.

Direct friendship with the palace and the people

Many saw New Delhi’s decision to invite the King to 2013’s Republic Day ceremony as a signal that it wants to directly deal with the palace and the people. All Bhutanese Kings, according to them, have been great protagonists of India-Bhutan friendship.

A revision of the India-Bhutan Treaty, 1949

It was perhaps because of this that New Delhi in 2007 agreed to revise the 1949 India-Bhutan Treaty after the king reportedly expressed his wish to have an agreement suitable to a country on the threshold of democracy. The revised treaty gave Thimphu freedom to pursue an independent foreign policy. A year later, the kingdom embraced democracy.

The revision of the treaty enabled the DPT government to extend Bhutan’s diplomatic ties from 21 to 53 countries between 2008 and 2013. New Delhi apparently wanted Thimphu to take geo-political realities into consideration while expanding its diplomacy across the globe.

Bhutan’s political system

In 2008, DTP won 45 of 47 seats and PDP two.

Bhutan follows a bi-party system. In the primary round that was held weeks ago to choose the top two parties for Saturday’s polls, DPT won in 33 and PDP 12. The remaining two seats went to Druk Nyamdrup Tshogpa that merged with the PDP.

June 2014: Indian PM's tour

10 key points of PM Narendra Modi's Bhutan visit

The Times of India TNN | Jun 16, 2014

His 2-day Bhutan trip was Prime Minister Narendra Modi's first foreign trip since assuming charge. During Modi's tour, both countries reaffirmed their commitment to extensive development cooperation and discussed ways to further enhance economic ties.

Here are some of the key points of Modi's visit to the Himalayan nation:

1. India and Bhutan reiterated their commitment to achieving the 10,000 MW target in hydropower cooperation and not to allow their territories to be used for interests "inimical" to each other.

2. Modi inaugurated one of India's assistance projects - the building of the Supreme Court of Bhutan and laid foundation stone of the 600MW Kholongchu Hydro-electric project, a joint venture between India and Bhutan.

3. India also announced a number of measures and concessions including the exemption of Bhutan from any ban on export of milk powder, wheat, edible oil, pulses and non-basmati rice.

4. The two sides recalled the free trade arrangement between them and the expanding bilateral trade and its importance in further cementing their friendship.

5. Prime Minister Narendra Modi also mooted the idea of an annual hill sports festival with India's northeastern states along with Bhutan and Nepal.

6. Modi announced doubling of scholarships being provided to Bhutanese students in India which will now be worth Rs 2 crore.

7. India will also assist Bhutan set up a digital library which will provide access to Bhutanese youth to two million books and periodicals.

8. Both India-Bhutan reaffirmed their commitment to extensive development cooperation and discussed ways to further enhance economic ties.

9. Modi described Bhutan as a natural choice for his first visit abroad as the two countries shared a "special relationship.

10. The fact that the Prime Minister chose Bhutan as his first foreign destination assumes significance since China has lately intensified efforts to woo it and establish full- fledged diplomatic ties with Thimphu.

Bhutan’s relations with China

Developments of 2013

Bhutan’s road to democracy leads to China?

Sachin Parashar | TNN 2013/06/26

New Delhi: There’s a new anxiety in the top echelons of New Delhi about what’s arguably India’s only friendly neighbour, Bhutan. As the hill kingdom takes another baby step in its transition from monarchy to democracy with its second parliamentary election on July 13, 2013, there’s realization here that complacence has possibly allowed some disturbing developments there to go unnoticed.

Friendship with Bhutan is often taken for granted by India’s foreign policy mandarins. So, it was a rude shock when they learnt last year from a Chinese press release that the new Bhutan PM, Jigme Thinley, has had a meeting with the then Chinese premier Wen Jiabao and the two countries were set to establish diplomatic ties.

Given that Bhutan’s foreign policy is, by and large, handled by New Delhi, such an important step without its knowledge created disquiet.

Purchase of 20 Chinese buses

Although the PM’s office in Thimpu sought to play it down, senior officers recalled that Thinley had said months after taking over as PM that he only saw growing opportunities in China and no threat. As part of Bhutan’s outreach to China was the decision last year to procure 20 Chinese buses, typically the kind of purchase that would normally be booked with, say, Tata Motors.

It raised eyebrows. It did not help that the person who got the contract for supplying the buses was reported to be a relative of Thinley.

Thinley: the best upholder of Bhutan’s ties with India

What’s ironic is that in his poll campaign, Thinley is said to be impressing upon the electorate that he was the best upholder of Bhutan’s ties with India, whereas he has possibly complicated them. Thinley’s Bhutan Peace and Prosperity Party is again the main contender for power in this tiny, landlocked nation of 700,000 which saw transition to democracy from an over 100-year-old hereditary monarchy in 2008.

Democracy in Bhutan

Democracy in Bhutan was ushered in by Bhutan’s benevolent fourth king Jigme Singye Wangchuck. May 2013 saw the Bhutanese repose faith in the system with 55% of 380,000-strong electorate braving thunderstorms and landslides to exercise their franchise.

As the world’s largest democracy, India welcomed Bhutan’s transition in 2008, but not everyone in South Block realized that the proposed model wasn’t like India’s Westminister model of parliamentary democracy. It’s a diarchy in Bhutan with the monarch retaining certain overriding powers.

Article 20.7 of Bhutan’s Constitution says the cabinet shall be collectively responsible to the Druk Gyalpo (the king) and to Parliament”. The government must also enjoy the confidence of the king as well as parliament. Further Article 20.4 says “the PM shall keep the Druk Gyalpo informed from time to time about the affairs of the state, including international affairs, and shall submit such information and files as called for by the Druk Gyalpo”.

Bhutan’s expansion of diplomatic ties

It now appears that the king wasn’t quite in the loop as Bhutan expanded its diplomatic ties with 53 countries, as against 22 in 2008, as well as its overture to Beijing to enhance ties with China which has maximum significance for India. If he hasn’t stepped in, it is to avoid any unintended signalling for the growth of democracy in Bhutan.

See also

Bhutan: Foreign policy