Bulandshahr District

Contents |

Bulandshahr District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Physical aspects

District in the Meerut Division, United Provinces, lying between 28° 4' and 28°43'N, and 77° 18' and 78° 28' E., with an area of 1,899 square miles. It is situated aspects ^" ^^^® l^o^h or alluvial plain between the Ganges

and Jumna, which form its eastern and western boun- daries, dividing it from Moradabad and Budaun, and from the Punjab Districts of Delhi and Gurgaon, respectively. On the north and south lie Meerut and Aligarh Districts. The central portion forms an elevated plain, flanked by strips of low-lying land, called khadar, on the banks of the two great rivers. The Jumna khadar is an inferior tract, from 5 to 10 miles wide, except in the south, where the river flows close to its eastern high bank. The swampy nature of the soil is increased in the north by the two rivers, Hindan and Bhuriya, but flooding from the Jumna has been prevented by the embankments protecting the head- works of the Agra Canal, The Ganges khadar is narrower, and in one or two places the river leaves fertile deposits which are regularly cultivated. Through the centre of the upland flows the East Kali Nadi, in a narrow and well-defined valley which suffers from flooding in wet years. The western half contains a sandy ridge, now marked by the Mat branch of the Upper Ganges Canal and two drainage lines known as the Patwai and Karon or Karwan. The eastern portion is drained by another channel called the Chhoiya. The whole of this tract is a fertile stretch of country, which owes much to the extension of canal-irrigation.

The soil is entirely alluvium in which kankar is the only stone found, while the surface occasionally bears saline efflorescences.

The flora of the District presents no peculiarities. At one time thick jungle covered with dhak {Butea fro?idosa) was common; but the country was denuded of wood for fuel when the East Indian Railway was first opened, and trees have not been replanted. The commonest and most useful trees are the babul and kikar {Acacia arabica and A. ebiirnia). The shisham {Dalbergia Sissoo), nim {Melia Azadirachta), z.x\di plpal {Ficus religiosa) are also common. In the east the landlords have encouraged the plantation of fine mango groves.

Wild hog and hog deer are common in the khadar. Both antelope and n'l/gai are found in the uplands, but are decreasing owing to the spread of cultivation. The leopard, wolf, and hyena are occasionally met with. In the cold season duck and snipe collect in large numbers on the ponds and marshes. Fish are not much consumed in the Dis- trict, though plentiful* in the rivers.

The climate resembles that of Meerut District, but no meteoro- logical observations are made here, except a record of rainfall. The extension of canal-irrigation has increased malaria, but its effects have been mitigated by the improvement of the drainage system.

The annual rainfall averages about 26 inches, of which 24 inches are usually measured between June i and the end of October. Large variations occur in different years, the fall varying from under 15 inches to over 40 inches. There is not much difference between the amounts in different parts of the District, but the eastern half receives slightly more than the western.

History

The early traditions of the people assert that the modern District of Bulandshahr formed a portion of the Pandava kingdom of Hastinapur, and that after that city had been cut away by the Ganges the tract was administered by a governor who resided at the ancient town of Ahar. Whatever credence may be placed in these myths, we know from the evidence of an inscription that the District was inhabited by Gaur Brahnians and ruled over by the Gupta dynasty in the fifth century of our era. Few glimpses of light have been cast upon the annals of this region before the advent of the Muhammadans, with whose approach detailed history begins for the whole of Northern India.

In 10 18, when Mahmild of Ghazni arrived at Baran (as the town of Bulandshahr is sometimes called to the present day), he found it in possession of a native prince named Har Dat. The presence of so doughty an apostle as Mahmud naturally affected the Hindu ruler; and accordingly the Raja himself and 10,000 followers came forth, says the Musalman historian, 'and proclaimed their anxiety for conversion and their rejection of idols.' This timely repentance saved their lives and property for the time ; but Mahmud's raid was the occasion for a great immigration towards the Doab of fresh tribes who still hold a place in the District.

In 1193 Kutb-ud-din appeared before Baran, which was for some time strenuously defended by the Dor Raja, Chandra Sen ; but through the treachery of his kinsman, Jaipal, it was at last captured by the Musalmans. The traitorous Hindu accepted the faith of Islam and the Chaudhriship of Baran, where his descendants still reside, and own some small landed property. The fourteenth century is marked as an epoch when many of the tribes now inhabiting Bulandshahr first gained a footing in the region. Numerous Rajput adventurers poured into the defenceless country and expelled the Meos from their lands and villages.

This was also the period of the early Mongol invasions ; so that the condition of the Doab was one of extreme wretchedness, caused by the combined ravages of pestilence, war, and famine, with the usual concomitant of internal anarchy. The firm establishment of the Mughal dynasty gave a long respite of tranquillity and comparatively settled government to these harassed provinces. They shared in the administrative recon- struction of Akbar ; their annals are devoid of incident during the flourishing reigns of his great successors. Here, as in so many other Districts, the proselytizing zeal of Aurangzeb has left permanent effects VOL. IX. E in the large number of Musalman converts ; but Bulandshahr was too near the court to afford much opportunity for those rebellions and reconquests which make up the chief elements of Mughal history. During the disastrous decline of the imperial power, which dates from the accession of Bahadur Shah in 1707, the country round Baran was a prey to the same misfortunes which overtook all the more fertile provinces of the empire. The Gvijars and Jats, always to the front upon every occasion of disturbance, exhibited their usual turbulent spirit ; and many of their chieftains carved out principalities from the villages of their neighbours. But as Baran was at this time a dependency of Koil, it has no proper history of its own during the eighteenth century, apart from that of Aligarh District. Under the Maratha rule it continued to be administered from Koil ; and when that town with the adjoining fort of Aligarh was captured by the British in 1803, Buland- shahr and the surrounding country were incorporated in the newly formed District.

The Mutiny of 1857 was ushered in at Bulandshahr by the revolt of the gth Native Infantry, which took place on May 21, shortly after the outbreak at Aligarh. The officers were compelled to fly to Meerut, and Bulandshahr was plundered by a band of rebellious Gujars. Its recovery was a matter of great importance, as it lies on the main road from Agra and Aligarh to Meerut. Accordingly, a small body of volun- teers was dispatched from Meerut for the purpose of retaking the town, which they were enabled to do by the aid of the Dehra Gurkhas.

Shortly afterwards, however, the Gurkhas marched off to join General AVilson's column, and the Gujars once more rose. Walidad Khan of Malagarh put himself at the head of the movement, which proved strong enough to drive the small European garrison out of the District. From the beginning of July till the end of September ^N^alidad held Bulandshahr without opposition, and commanded the line of com- munication with Agra. Meantime internal feuds went on as briskly as in other revolted Districts, the old proprietors often ousting by force the possessors of their former estates.

But on September 25 Colonel Greathed's flying column set out from Ghaziabad for Bulandshahr, whence ^^'alTdad was expelled after a sharp engagement and forced to fly across the Ganges. On October 4 the District was regularly occu- pied by Colonel Farquhar, and order was rapidly restored. The police were at once reorganized, while measures of repression were adopted against the refractory Gujars, many of whom still continued under arms. It was necessary to march against rebels in Etah early in 1858 ; but the tranquillity of Bulandshahr itself was not again disturbed. Throughout the progress of the Mutiny, the Jats almost all took the side of Government, while the Gujars and Musalman Rajputs proved our most irreconcilable enemies.

Two important copperplate inscriptions have been found in the ])istrict, one dated a. d. 465-6 of Skanda Gupta, and another giving the h'neage of the Dor Rajas. There are also ancient remains at Ahar and Bulandshahr. A dargdh was built at Bulandshahr in 1193, when the last Dor Raja was defeated by the Muhammadans ; and the town contains other buildings of the Muharamadan period.

Population

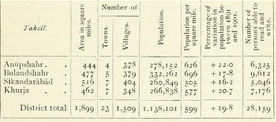

The number of towns and villages in the District is 1,532. Popula- tion has increased considerably. The numbers at the last four enumera- tions were as follows : (1872) 937,427, (1881) 924,822, (1891) 949,914, and (1901) 1,138,101. The tempo- rary decline between 1872 and 1881 was due to the terrible outbreak of fever in 1879, which decimated the people. The increase of nearly 20 per cent, during the last decade was exceeded in only one District in the Provinces. There are four tahslls — Anupshahr, Bulandshahr, SiKANDARABAD, and Khurja — the head-quarters of each being at a town of the same name. These four towns are also municipalities, and the last three are the chief places in the District.

The principal statistics in 1901 are given below : —

In 1901 Hindus numbered 900,169, or 79 per cent, of the total; Musalmans, 217,209, or 19 per cent.; Aryas, 12,298; and Christians, 4,528. The number of Aryas is greater than in any other District in the Provinces, and the Samaj has twenty-seven lodges or branches in Bulandshahr. Practically all the inhabitants speak Western Hindi. In the north the dialect is Hindustani, while in the south Braj is commonly used.

Among Hindus the most numerous castes are Chamars (leather- workers and labourers), 183,000, who form one-fifth of the total ; Brahmans, 113,000; Rajputs, 93,000; Jats, 69,000; Lodhas (culti- vators), 64,000; Banias, 56,000; and Gujars, 44,000, The Brahmans chiefly belong to the Gaur clan, which is peculiar to the west of the Provinces and the Punjab, while Jats and Gujars also are chiefly found in the same area. The Lodhas, on the other hand, inhabit the central Districts of the Provinces.

The Meos or Mlnas and Mewatis are immigrants from Mew at ; and among other castes pecu- liar to this and a few other Districts may be mentioned the Orhs (weavers), 4,000, and Aherias (hunters), 4,000. The Musalmans of nominally foreign extraction are less numerous than those descended from Hindu converts. Shaikhs number 24,000; Pathans, 17,000; Saiyids, 6,000 ; and Mughals only 3,000 ; while Musalman Rajputs number 34,000; Barhais (carpenters), 15,000; Telis (oil-pressers), 11,000; and Lobars (blacksmiths), 11,000. About 51 per cent, of the population are supported by agriculture. Rajputs, both Musal- man and Hindu, Jats, Saiyids, and Banias are the largest landholders ; and Rajputs, Brahmans, and Jats the principal cultivators. General labour supports 11 per cent, of the total population, personal service 9 per cent., weaving 3 per cent., and grain-dealing 3 per cent.

Of the 4,480 native Christians in 1901, 4,257 belonged to the American Methodist Episcopal Church, which started work here in 1887. Most of them are recent converts, chiefly from the lower castes. The Zanana Bible and Medical Mission and the Church Missionary Society have a few stations in the District.

Agriculture

Excluding the Jumna and Ganges k/uldars, the chief agricultural defect is the presence of barren fisar land covered with saline efflor- escences called reh, which occurs in badly-drained localities, and spreads in wet years. The District is remarkable for the absence of grazing-grounds, fodder-crops being largely grown. Where conditions are so uniform, the chief variations are due to the methods employed by different castes, among whom Ahirs and Jats take the first place. The Ahirs devote most attention to the area near the village site and prefer well-irrigation, while the Jats do equal justice to all good land and use canal water judiciously. The Lodhas come next and are as industrious as the Jats, but lack their physique. Giijars are usually inferior.

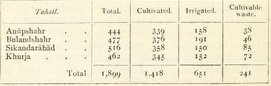

The tenures are those common to the United Provinces ; but the District is marked by the number of large estates. Out of 3,440 mahals at the last settlement, 2,446 were zamlnddri or joint zamin- ddri, 546 bhaiydchdra, and 448 pattiddri or imperfect pattlddri. The main statistics of cultivation in 1903-4 are shown below, in square miles : — -

The chief food-crops and the area occuj)icd by each in siiuarc miles were: wheat (424), gram (199), maize (188), barley {2 2']),Jo7var (156), and bdjra (121). The area under maize has trebled during the last twenty-five years. Bajra is chiefly grown on inferior soil in the Sikandarabad and Khurja tahstls. The other important crops are cotton (103) and sugar-cane (63), both of which are rapidly increas- ing in importance. On the other hand, the area under indigo has declined from 120 square miles in 1885 to 25 in 1903-4.

From 1870 to 1874 a model farm was maintained at Bulandshahr, and attempts were made to introduce Egyptian cotton ; but these were not successful. The chief improvements effected have been the exten- sion of canal-irrigation, and its correction by means of drainage cuts. Much has also been done to straighten and deepen the channels of the rivers described above, especially the East Kali Nadi. These have led to the extended cultivation of the more valuable staples. Very few advances have been made under the Agriculturists' Loans Act, and between 1891 and 1900 only Rs. 30,000 was given under the Land Improvement Loans Act. In 1903-4 the loans were Rs. 1,700. The agricultural show held annually at Bulandshahr town has done much to stimulate interest in small improvements.

An attempt was made in 1865 to improve the cattle by importing bulls from Hariana ; but the zamlndars were not favourable. The ordinary cattle are poor, and the best animals are imported from Rajputana, Mewar, or Bijnor. Horse-breeding has, however, become an important pursuit, and there are twenty stallions owned by Govern- ment in this District. The zaminddrs of all classes are anxious to obtain their services, and strong handsome colts and fillies are to be seen in many parts. Mules are also bred, and ten donkey stallions have been supplied. Since 1903 horse and mule-breeding operations have been controlled by the Army Remount department. Sheep and goats are kept in large numbers, but are of the ordinary inferior

type.

The District is exceptionally well provided with means of irrigation. The main channel of the Upper Ganges Canal passes through the centre from north to south. Near the eastern border irrigation is supplied by the Anupshahr branch of the same canal, while the western half is watered by the Mat branch. The Lower Ganges Canal has its head-works in this District, leaving the right bank of the Ganges at the village of Naraura. Most of the wells in use are masonry, and water is raised almost universally in leathern buckets worked by bullocks. In 1903-4 canals irrigated 323 square miles and wells 310. Other sources are insignificant.

Salt was formerly manufactured largely in the Jumna k/iddar, but none is made now. The extraction of sodium sulphate has also been forbidden. There are sixty factories where crude saltpetre is pro duced, and one refinery. Where kankar occurs in compact masses, it is quarried in blocks and used for building purposes.

Trade and Communication

Till recently Bulandshahr was one of the most important indigo- producing Districts in the United Provinces. There were more than 1 20 factories in 1891 ; but the trade has fallen off

Iradeana considerably, and in 1002 there were only 47, which communications. •; \ . .'

employed about 3,800 hands. Cotton is ginned and

pressed at 12 factories, which employ more than 900 hands; and this industry is increasing. The owners of the factories have imported the latest machinery from England. Other manufactures are not of great importance; but the calico-printing of JahangIrabad, the muslins of SiKANDARABAD, the pottcry of Khurja, the rugs of Jewar, and the wood-carving of Bulandshahr and Shikarpur deserve mention for their artistic merits. There is also a flourishing glass industry in the Bulandshahr tahsil, where bangles and small phials and bottles are largely made. Cotton cloth is woven as a hand industry in many places.

Grain and cotton form the principal exports ; the weight of cleaned cotton exported is nearly 4,000 tons, having doubled in the last twenty- five years. The imports include piece-goods, metals, and salt. Aniip- shahr is a depot for the import of timber and bamboos rafted down the Ganges ; but Khurja and Dibai have become the largest com- mercial centres, owing to their proximity to the railway. Local trade is carried on at numerous small towns, where markets are held once or twice a week.

The East Indian Railway runs from south to north through the western half of the District. For strategic reasons it was built on the shortest possible alignment, and thus passes some distance from the principal towns ; but a branch line is under construction, which will connect Khurja and Bulandshahr and join the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway at Hapur in Meerut District. A branch of the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway from Aligarh to Moradabad and Bareilly crosses the south-east corner.

There are 163 miles of metalled and 495 miles of unnietalled roads. The whole length of metalled roads is in charge of the Public Works department, but the cost of 109 miles of these, and the whole cost of the unmetalled roads, is met from Local funds. Avenues of trees are maintained on 257 miles. The principal line is that of the grand trunk road from Calcutta to Delhi, branches of which leave Bulandshahr for Meerut and Anupshahr. The only parts where com- munications are defective are the northern Jumna khadar and the north-eastern and south-eastern corners of the District.

Bulandshahr shared in the many famines which devastated the Upper Doab before British rule, and during the early years of the nineteenth century scarcity occurred several times.

Famine

In 1837 famine was severe, and its effects were increased by immigration from Hariana and Marwar and the Districts of Etawah and Mainpurl. The worst-affected tracts were the areas along the Jumna ; but the construction of the grand trunk road provided employment for many, and other works were opened. In i860 the same tracts suffered, being largely inhabited by Gujars, still impoverished owing to their lawlessness in the Mutiny, The Mat branch canal was started as a relief work. About Rs. 32,000 was spent on relief and Rs. 50,000 advanced for purchase of bullocks and seed, much of which was repaid later, and spent in constructing dispensaries. In 1S68-9, though the rains failed, there was a large stock of grain, and the spread of irrigation enabled spring crops to be sown. In 1877 and 1896-7 no distress was felt except among immigrants, and able-bodied labourers could always find work. In the latter period alone 1,518 wells were made, and the high price of grain was a source of profit.

The ordinary staff consists of a Collector, assisted by one member of the Indian Civil Service and three Deputy-Collectors recruited in India. There is a tahsilddr at the head-quarters of each of the four tahsih. Bulandshahr is also the head-quarters of an Executive Engineer of the Upper Ganges Canal.

Administration

For purposes of civil jurisdiction the District is divided between two Judgeships. The Sikandarabad tahsil belongs to the miinsifl of (ihaziabad in Meerut District, and appellate work is disposed of by the Judge of Meerut. The rest of the District is divided into two iminsifls, with head-quarters at Bulandshahr and Khurja, subordinate to the Judge of Allgarh. The additional Sessions Judge of Aligarh exer- cises criminal jurisdiction over Bulandshahr. The District has a bad reputation for crime, cattle-theft being especially common. Murders, robberies, and dacoities are also numerous. The Gujars are largely responsible for this lawlessness, being notorious for cattle-lifting.

Part of the District was acquired by cession from the Nawab ^^^azTr of Oudh in iSoi, and part was conquered from the Marathas in 1803. For twenty years the area now included lay parti)- in Allgarh, and partly in Meerut or South Saharanpur Districts. In 18 19, owing to the law- lessness of the Gujars, a Joint-lNIagistrate was stationed at Bulandshahr, and in 1823 a separate District was formed. The early land revenue settlements were of a summary nature, each lasting one, three, four, or five years. Tahikddrs, who were found in possession of large tracts, were gradually set aside. Operations under Regulation VII of 1822 were completed in only about 600 villages, and the first regular settle- ment was made between 1834 and 1837. The next settlement was commenced before the Mutiny, and was completed in 1865 ; but the project for a permanent settlement entailed a complete revision. This showed that there had been an extraordinary rise in rental 'assets,' which was partly due to survey errors, partly to concealments at the time of settlement, and partly to an increase in the rental value of land. The idea of permanently fixing the revenue was abandoned, and the demand originally proposed was sanctioned, with a few alterations, yielding 12-4 lakhs. The 'assets,' of which the revenue formed half, were calculated by fixing standard rent rates for different classes of soil.

These rates were derived partly from average rents and partly from valuations of produce. The latest revision of settlement was completed between 1886 and 1889, and was notorious for its results. The assess- ment was to be made on the actual rental ' assets ' ; but the records were found to be unreliable on account of the dishonesty of many land- lords, who had deliberately falsified the pativaris' papers, thrown land out of cultivation, and stopped irrigation. The tenants, who had been treated harshly and not allowed to acquire occupancy rights, themselves came forward to expose the fraud. Large numbers of rent-rolls were entirely rejected, and the villages they related to were valued at circle rates. The circle rates were obtained by an analysis of rents believed to be genuine. While the settlement of most of the District was con- firmed for thirty years, a number of villages were settled for shorter terms to enable the settlement to be made on the basis of a fair area of cultivation. The total demand was fixed at 19-8 lakhs, which has since risen to 20 lakhs. The incidence per acre is Rs. 1-15-0, varying in different parts of the District from Rs. 1-2-0 to Rs. 2-9-0.

("ollections on account of land revenue and total revenue have been, in thousands of rupees : —

There are four municipalities— Bulandshahr, Anupshahr, Sikan- DARABAD, and Khurja — and 19 towns are administered under Act XX of 1856. Outside these, local affairs are managed by the District board. In 1903-4 the income of the latter was 1-9 lakhs, chiefly derived from local rates. The expenditure was 2 lakhs, of which Rs. 96,000 was spent on roads and buildings.

In 1903 the District Superintendent of police was assisted by four inspectors. The force numbered 106 officers and 355 constables, be- sides 369 municipal and town police, and 1,979 village and road police. The District jail contained an average of 232 [)risoners in the same year.

Bulandshahr is backward in literacy, and only 2-5 percent. (4-5 males and 0-3 females) of the population could read and write in 190 1. In 1 88 1 there were 130 public schools with 4,486 pupils, and the numbers rose in 1901 to 171 schools with 7,989 pupils. In 1903-4 there were 187 public schools with 10,801 pupils, of whom 57 were girls, and also 271 private schools with 4,157 pupils. The total expenditure on education was Rs. 49,000, of which Local and municipal funds supplied Rs. 38,000, and fees Rs. 11,000. Of the public schools, two were managed by Government and 117 by the District and municipal boards.

The District has nine hospitals and dispensaries, with accommoda- tion for 109 in-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 101,000, of whom 2,300 were in-patients, and 8,400 operations were performed. The expenditure in the same year was Rs. 18,000, chiefly from Local funds.

In 1903-4, 39,000 persons were successfully vaccinated, represent- ing a proportion of 34 per 1,000 of population. Vaccination is com- pulsory only in the municipalities.

[F. S. Growse, Bulandshahr (Benares, 1884) ; T. Stoker, Settlement Report (1891); H. R. Nevill, District Gazetteer {ii)o^)J]