Bus Rapid Transit (BRT): Delhi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

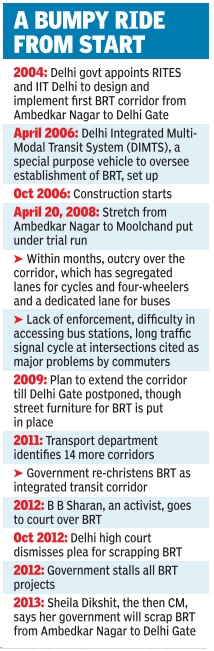

History

The Times of India, January 20, 2016

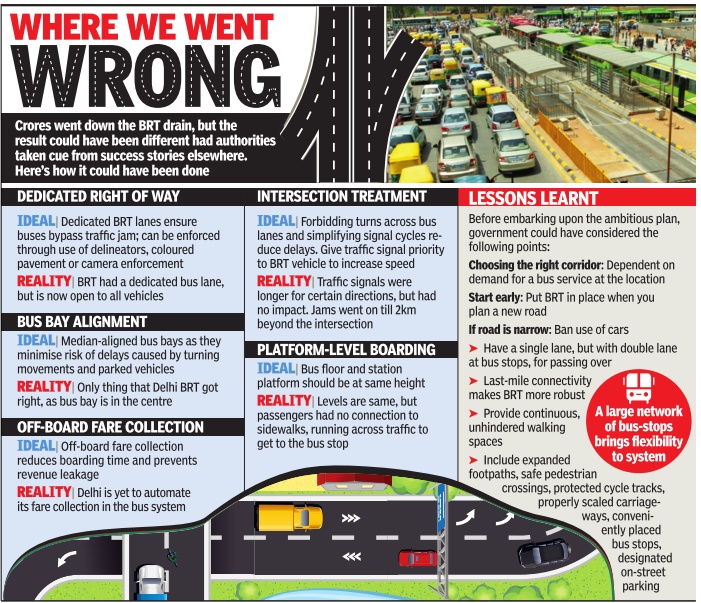

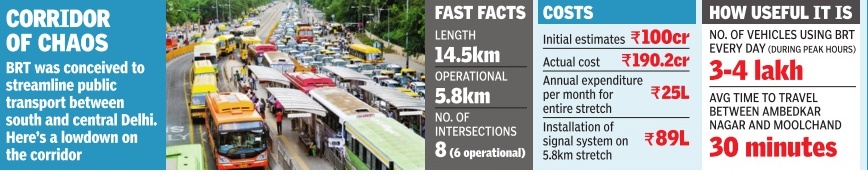

Flawed from the beginning: Not closed to other traffic When the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor was first planned in 2004, the idea was simple: a dedicated lane for buses would make travel faster. The implementation and design, however, proved to be its undoing. Several flaws in both proved to be fatal for the corridor.

The fact, though, is that BRT can work. In Ahmedabad, for example, it has made public transport the preferred option for many because of ease and accessibility. It has been a success in Pune as well.

According to experts, the exercise failed in Delhi primarily because there was no control over its design and implementation. The lack of a single agency that could be held accountable also proved to be a problem. While DIMTS, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) set up to manage BRT, ran the stretch, policymaking and enforcement were out of its hands. In contrast, in Ahmedabad, Janmarg, an SPV controlled by the municipality , manages the BRTS completely . This agency planned, designed, implemented and managed the corridor, resulting in direct accountability .

Ahmedabad also learnt from others, including Delhi's mistakes. Instead of going with an open system, which would allow other vehicles to enter and exit the dedicated lanes, Ahmedabad opted for a closed BRT. In Delhi, the pilot 5.8km stretch between Ambedkar Nagar and Moolchand had a dedicated bus lane, with the car lane being squeezed into just two lanes on either side. Signal cycles went for a toss with a long waiting time at intersections. Bus stations, which were supposed to provide safe entry and exit to the bus system, became hazardous as they were located near the intersections -adding to traffic congestion -and were diffi cult to negotiate for commuters.

The Ahmedabad BRTS couldn't be more different. It uses smart cards, air-conditioned buses, dedicated fast lanes, a public information system, global positioning system and a centralised con trol room. It is a closed BRT system. So, the buses don't go out and other buses are not allowed in. The buses are fitted with devices which traffic signals can read and give them free passage. The bus stations are located more than 300m before the intersections and have platform screen doors operated by sensors to prevent people from getting hit by buses passing by. The doors open when a bus arrives and all buses, standard floor ones, stop in perfect alignment with the floor of the bus shelters.

What made the biggest difference perhaps was the fact that people were allowed to give feedback that was incorporated by the Ahmedabad municipal corporation.In fact, before the launch, people were given free rides for two months on the buses plying on the Ahmedabad BRTS.

The short distance of the pilot BRTS project in Delhi also sounded its death-knell.The fact is that 5.8km will never showcase the benefits of a system, however good it may be. Better design also proved to be Ahmedabad BRTS' advantage. Central lanes ensure that interference from the traffic is minimized while bus stations far from intersections ensure that queues of buses do not create jams. Together, these measures led to increased bus frequencies and reduced the waiting period to 2 minutes during peak hours and 8-10 minutes during off-peak hours. Compare that with the Delhi model, where the waiting time at intersections was more than 20 minutes during peak hours.

2012

The Times of India, Jul 22 2015

RRI had asked for scrapping of corridor

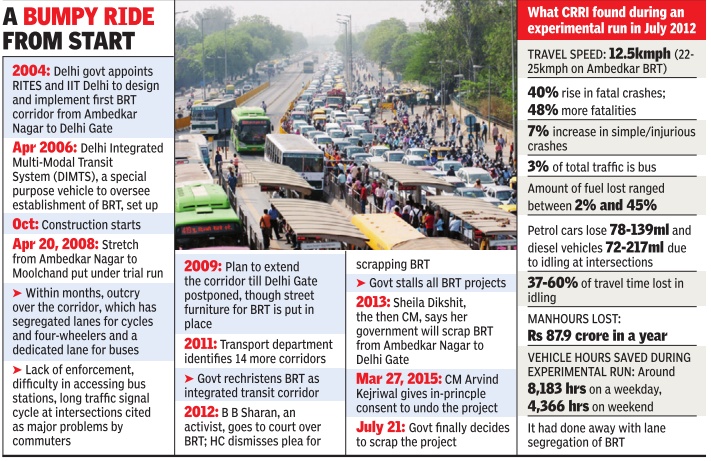

In 2012, the Delhi high court had asked Central Road Research Institute (CRRI) to determine the operational effectiveness of the BRT corridor. CRRI conducted a trial run on the 5.8km stretch both as a BRT and a normal road and recommended scrapping it. The institute's report clearly states: “The no-BRT option yields better benefits for this corridor“ and adds, “The trial run scenario would reduce the total travel time and stop delay in the year 2015 by 39% and 48% respectively.“ CRRI said letting other vehicles use the lane reserved for buses yielded “benefits for all the road-users compared to BRT situation“.

The study showed that the BRT had not only increased travel time but also the frequency of accidents. Above all, CRRI found out that the then government's most important reason for continuing with the corridor--that it served a large number of people travelling by bus--was not supported by facts. The re port said buses tended to clump together in the corridor as the routes had not been rationalized, and only 4-5 passengers boarded or alighted per bus. This, the report said, “is obviously boosting the passengers per-hour-per-direction drastically and thus presenting an exaggerated figure.“

The CRRI report also rubbished claims that the BRT has reduced the number of fatal and serious injuries or crashes on the stretch. Using police records, it showed that fatal road accidents had increased by 40% and the number of deaths by 48% after the BRT became operational. “At the same time, the number of simple injurious road crashes reported by the traffic police has registered an increase of 7%,“ the report said.

The study showed fuel consumption on the stretch had increased significantly .Idling at intersections led to losses of 78139ml for every petrol car, and 72-217ml for diesel cars through the day .The fuel loss ranged from 2% to 45%, said the report and the maximum wastage was on the stretch between Sheikh Sarai and Chirag Dilli, where it ranged from 17% to 41% through the day . The time wasted in idling ranged from 37% to 60% of the journey time, which amounted to many thousands of manhours every day .

“The evaluation of passenger hours in terms of monetary value shows there is a loss of Rs 87.91 crore in a year during normal BRT operation compared with the experimental run,“ the report stated. The total number of vehicle-hours saved during the experimental run--when the BRT was used as a normal road--was around 8,183 on a weekday and 4,366 on weekends for the 16-hour study duration, said the report.

A Wastage of time and money

Mar 27 2015

Clearing BRT will be a multi-crore job

Dismantling corridor will need another 4 months during which commuters can expect more traffic chaos. But right now, the project seems to be nobody's responsibility

Once the BRT corridor is dismantled, the space that will open up will be sufficient for a six-lane road.And then, three lanes on each carriageway will be open to both public transport and private vehicles. The pedestrian and cycling path will continue to remain as they exist. The construction cost of the project was around Rs 190 crore. It took another Rs 15-18 crore to maintain the corridor. Dismantling it will take anywhere between Rs 3.5 crore and Rs 11.5 crore, depending on whether the entire 5.8-km stretch is re-carpeted or repaired in parts.

While no instructions have been issued to PWD to start dismantling the corridor, officials estimate that work may take up to four months through which commuters can expect more traffic jams as the road will be closed in parts to allow work to take place. “The major work is that of dismantling the bus Q shelters and setting them up again. When they are set up again, a foundation will have to be built first. This is time consuming, especially since there will be a total of 20-odd such stops to be set up on either side of the road. Dismantling or re-installing of each shelter will cost Rs 10 lakh or so,“ said a source.

Government officials said next major work would be removal of the stones from the middle of the road that work as dividers. Along with this, the signalling system will have to be changed while the road may need to be re-paved entirely. “The signalling sys tem itself is such a waste.Close to Rs 90 lakh was spent on it though it hardly ever works and signalling is often done manually . A lot of money has been spent on the project but considering the dangers it poses, the government will have to spend a little more and improve the corridor,“ said an official.

The work of removing the stones will require very little funds since it will be done manually, say sources. However, the other major expenditure that will be incurred will be in repairing the road.“Once the bus shelters and stones are removed, they will leave patches of broken road behind. These will have to be repaired. Once directions come from the government, the entire stretch will be surveyed to see whether all of it has to be relaid or only parts of it have to be repaired. If the entire stretch is relaid, it will cost around Rs 10 crore while repairs will cost about Rs 2 crore,“ added the source.

The project also seems to be nobody's responsibility right now. The operations and maintenance were with DIMTS until recently but the lieutenant governor asked PWD to take over the work.While maintenance is in the process of being handed over to PWD, the agency refused to take up work of operating the corridor, citing lack of expertise in the field. Consequently, nobody seems to be managing the corridor at present.

Slowed the police

The Times of India Mar 27 2015

Somreet Bhattacharya

Traffic cops have been facing a challenge in controlling traffic between Ambedkar Nagar and Moolchand due to the lack of lane discipline and confusion because of multiple signaling in the Bus Rapid Transit system. Traffic officials welcomed the plans to remove the BRT, but have suggested other places where the system can be put into place. “We are not against BRT, but the plan should have been implemented after a study of the composition of traffic and commuters travelling on this stretch. At present, only a fraction of the total capacity of the BRT is in use,“ said Muktesh Chander, special commissioner (traffic).

A senior traffic officer pointed out three major problems that could not be addressed even after they were given control of signals on this stretch. One of the problems was the difference in signal timing.

Traffic police in a report had pointed out the lack of proper movement of pedestrians from bus shelters in the middle of the road to pavements. Data shows at least five pedestrians are hit by vehicles in the process every day . To reach the bus shelter, a pedestrian has to wade through oncoming traffic increasing the potential of an accident.

The third issue is lack of connectivity of the corridor to any other point. “This has made the stretch unpopular,“ said a traffic police officer. Police had suggested that BRT could be introduces at GT Road in north-east Delhi, parts of Outer Ring Road in Rohini and parts of Najafgarh Road.

In the high court

The Times of India Mar 27 2015

Abhinav Garg

HC had refused to judge the BRT battle

It took a government with a huge majority to finally wind up the controversial BRT corridor.The debate over utility of the stretch in south Delhi has remained mostly stuck to “rich car owner versus poor bus commuter“ framework, despite studies showing how the corridor created traffic bottlenecks for every category of vehicles. Even before Delhi high court, where the BRT system was repeatedly challenged, the then state government portrayed as if only a small section of car owners complained while a large category of daily passengers using public transport were satisfied.

The government's stand ignored a scathing report filed by Central Road Research Institute (CRRI) in 2012 that said that due to demarcation of lanes, a lot of time and fuel was being wasted every day . The report, prepared after several trial runs on the corridor, suggested that `NO BRT' option was most suitable under present traffic conditions.

During court hearings, the state government had dismissed the CRRI report terming it “unconstitutional“ and “irrational“ as it ignored the rights of bus commuters. Its stand was supported by advocate Prashant Bhushan who represented NGO National Alliance of People's Movement. Bhushan trashed the CRRI study as “unscientific“ and anti poor commuter.

In its verdict the same year, the court dismissed a petition by NGO Nyaya Bhoomi seeking scrapping of the corridor. It said courts should not interfere with a policy matter aimed at promoting public transport. “Within the parameters of a scope of judicial review, the scattered material placed before us would not justify a conclusion that BRT as a concept is bad and is a misfit in Delhi and thus should be scrapped,“ the HC had observed.

The court had said motorists sooner or later would shift to public transport due to limited scope of expanding the width of roads. “Even if we were to accept the argument that as of today , with the implementation of BRT corridor some inconvenience is being caused, across the board, to everybody... there being no scope to expand the width of existing roads... We see no escape from the fact that citizens of Delhi have to, one day or the other, use public transport,“ it noted.

Dismantling BRT

Also a failure

From: Paras Singh & Mayank Manohar, Why dismantling of BRT is as big a failure as corridor itself, August 15, 2018: The Times of India

Commuters Brave Daily Traffic Snarls As Revamp Plan Lies In Disarray

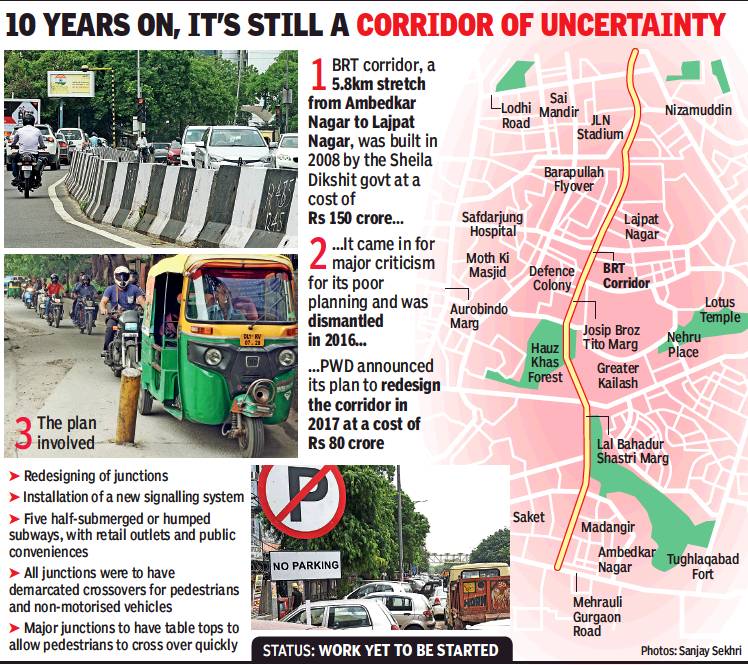

Two years ago, the existing bus rapid transport corridor from Ambedkar Nagar to Moolchand, built by the Sheila Dikshit government, was dismantled with great fanfare. If that did any good, there is no indication of it. Today, traffic jams on the stretch are so common as to have roundly defeated the purpose of the demolition.

The Public Works Department planned to redesign the BRT corridor into a regular road, and the 5.8 kilometres from Ambedkar Nagar to Lajpat Nagar were to have seen a Rs 80-crore revamp with new junctions, installation of traffic signals and construction of overbridges and subways.

The tender for the project was to have been floated in 2017, but all plans got stuck when, according to PWD officials, the urban development department suggested a few changes. “We are working on the suggestions because they will help bring down the project cost,” claimed a senior official. “Once the changes are approved by the government, the tender will be called for.”

PWD officials maintained it was too early to give a completion date because the project deadline depended on the sanction and approval of the government. The tendering process itself is likely to take up to eight month before work can start on the ground.

Till then, as TOI found when it visited the corridor, traffic will remain haphazard. Curiously, even the road width is inconsistent, with space used up by the bicycle track. In any case, the track designed for bicycles, especially between Moolchand flyover and Chirag Dilli intersection, is freely used now by two wheelers and even by cars at times.

To add to the problem, from the exit of the slip road at Masjid Moth onward, most side areas have turned into illegal dumps for debris in plain sight of numerous signboards warning people not to dump waste there. TOI also found the road space being encroached by vendors and car repair workshops. Near the Jahanpanah City Forest exit, construction material in the form of concrete blocks lies across the approach. Crossing the Chirag Dilli intersection towards Ambedkar Nagar brings you in sight of illegal parking spaces.

“During peak traffic hours, I have got stuck here for up to 40 minutes. What was the point of spending crores to demolish the BRT if things were not going to improve?” asked Animesh Sinha, a BPO worker and daily commuter. His plaint is apparent. The central verge on the entire length consists of concrete bollards. The lack of a proper road divider has created several bottlenecks for road users.

Pedestrians are perhaps the worst off. The entire stretch has only one dilapidated foot overbridge near the Ambedkar Nagar junction. Most footpaths have been converted into illegal parking lots. Ranbir Singh, a resident of Madangir, observed that crossing the road means risking life given the traffic volume. “You not only have to face reckless traffic, but also look over the shoulder because many cars drive in the wrong direction,” Singh complained. For him, life seems only to have jumped from the frying pan into the fire in the past two years.