Capital punishment: India

(→Arbitrary imposition of death penalty) |

|||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

Suhas Chakma of the Asian Centre for Human Rights blamed executions by the state as `politically motivated'. “The fact that few sentences have been confirmed by the high courts and even fewer by the Supreme Court in comparison to the number of cases reported in the NCRB, shows that death penalty has no impact and it has no use,“ he said. | Suhas Chakma of the Asian Centre for Human Rights blamed executions by the state as `politically motivated'. “The fact that few sentences have been confirmed by the high courts and even fewer by the Supreme Court in comparison to the number of cases reported in the NCRB, shows that death penalty has no impact and it has no use,“ he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | = Who should debate death penalty: SC or Parliament?= | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=LEGALLY-SPEAKING-Who-should-debate-retention-of-death-03082015011082 ''The Times of India''], Aug 03 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dhananjay Mahapatra | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the past many decades, we have witnessed a psychological and constitutional battle between two classes -those seeking abolition of death penalty and others who lean for its retention. | ||

| + | Yakub Abdul Razak Memon's last-gasp attempts to seek stay of his execution has brought the spotlight back on the debate between abolitionists and retentionists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Petitions to save Yakub from the gallows assumed a Phoenix-like character as the execution time approached.Dismissal of one was quickly followed by another. Such is the importance given to right to life by the Supreme Court that it opened its doors postmidnight and heard Yakub's plea till the crack of dawn. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The rejection of his final appeal drew the ire of activistlawyers who had virtually taken the legal battle as an all-out war against retentionists. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their sombre mood soon turned combative. Many renowned advocates who have doggedly fought for human rights for years sniped at the justice delivery system and government, saying a “lynch mob“ and “bloodlust“ attitude had resulted in a “tragic mistake by the SC“. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Till 1973, the law had given absolute discretion to the judges to choose between death penalty and life imprisonment in murder cases. Despite this, the SC had repeat edly cautioned the trial courts to exercise discretion, keeping in mind the criminal and not the crime. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1973, the new Criminal Procedure Code made it imperative that life imprisonment was the rule and death penalty the exception for murder convicts. It also said the judge was duty-bound to record special reasons for which heshe preferred to award death penalty instead of life term. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The analysis of `special reason' led the SC to devise the `rarest of rare' doctrine for award of death penalty in the Bachan Singh case in 1982 while upholding the validity of capital punishment. This we will deal with a little later. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even prior to the enactment of the new CrPC, a five judge SC bench in Jagmohan Singh vs state of UP (1973 AIR 947) had answered alleged arbitrariness in imposing death penalty , which the petitioner said extinguished every constitutional right of a convict, and that there was no guideline for judges in deciding which cases warranted imposition of capital sentence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It had said, “The exercise of judicial discretion on well-recognized principles is, in the final analysis, the safest possible safeguard for accused.“ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seven years later, a threejudge bench headed by Justice V R Krishna Iyer dealt with a similar question in Rajendra Prasad vs State of UP (1979 AIR 916). It had cautioned against individual cases being made examples to argue either for abolition or retention. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Personal story of an actor in a shocking murder, if considered, may bring tears and soften the sentence. He might have been a tortured child, an ill-treated orphan, a jobless man or the convict's poverty might be responsible for the crime,“ it had said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, it upheld the constitutional validity of death penalty saying there could be a situation where law-breakers brutally kill law enforcers trying to discharge their function. “If they are killed by designers of murder and the law does not ex press its strong condemnation in extreme penalization, justice to those called upon to defend justice may fail. This facet of social justice also may in certain circumstances and at certain stages of societal life demand death sentence.“ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Four years later, a constitution bench by four-to-one majority upheld the validity of death penalty in Bachan Singh case on August 16, 1982. It had classified murders into two broad categories -one committed purely for private reasons and the other which “unleash a tidal wave of such intensity , gravity and magnitude, that its impact throws out of gear the even flow of life“. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It explained the stand of abolitionists. “Statistical attempts to assess the true peno logical value of capital punishment remain inconclusive.Firstly , statistics of deterred potential murderers are hard to obtain. Secondly , the approach adopted by the abolitionists is over simplified at the cost of other relevant but imponderable factors, the appreciation of which is essential to assess the true penological value of capital punishment. The number of such factors is infinitude, their character variable, duration transient and abstract formulation difficult,“ it had said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, it had sounded caution. “Judges should never be blood-thirsty . Hanging of murderers has never been too good for them. Facts and figures, albeit incomplete, furnished by the Union of In dia, show that in the past, courts have inflicted the extreme penalty with extreme infrequency -a fact which attests to the caution and compassion they have always brought to bear on the exercise of their discretion.“ | ||

| + | |||

| + | The statistics and studies in the past few decades have been woefully inadequate to help the SC arrive at a definitive opinion about the efficacy of death penalty. It is time for abolitionists to spend their energies convincing representatives of people to raise the matter in Parliament and bring an amendment to the provisions of law providing for death penalty rather than blame the judiciary for imposing the punishment in `rarest of rare' murder cases. | ||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

[[Mercy petitions: India]] | [[Mercy petitions: India]] | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 4 August 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Section 364A of the Indian Penal Code

Sec 364A: Too harsh a provision?

TIMES NEWS NETWORK 2013/07/05

New Delhi: The Supreme Court had laid down the “rarest of rare” criteria for courts to award death penalty only in select heinous and gruesome murder cases.

In this background, can Parliament enact a law providing for mandatory death penalty for those found guilty of murdering a person after kidnapping him to demand ransom? Would this not amount to pushing every offence of kidnap for ransom involving murder of the victim into ‘rarest of rare’ category without a judicial determination to that effect?

This question was framed by Justices T S Thakur and S J Mukhopadhaya while referring to a petition challenging the constitutional validity of Section 364A of Indian Penal Code, which imposes mandatory death penalty in kidnap for ransom involving murder of the kidnapped.

The petition was filed by one Vikram Singh, who was convicted under Sections 302 (murder) and 364A of the IPC and awarded death penalty on both counts. The apex court had upheld his conviction and sentence.

But in his petition before the Supreme Court, his counsel D K Garg argued that if the court came to the conclusion that punishment provided under Section 364A of IPC was unconstitutional, then a lenient view could be taken on the death penalty awarded to his client under Section 302.

He argued that Section 364A made even a first time offender liable to be punished with death, which was too harsh to be considered just and appropriate.

Appearing for the Union government, additional solicitor general Sidharth Luthra argued, “It is within the legislative competence of Parliament to provide remedies and prescribe punishment for different offences depending upon the nature and gravity of such offences and the societal expectation for weeding out ills that afflict or jeopardize the lives of citizens and the security and safety of vulnerable sections of the society, especially children who are prone to kidnapping for ransom and being brutally killed if their parents are unable to pay the ransom amount.

“The provisions of Section 364A are not only intended to deal with cases of kidnapping for ransom involving murder of victim but also cases in which terrorists and other extremist organizations resort to kidnapping for ransom or to such other acts only to coerce the government to do or not to do something.”

The court agreed with Luthra that the petitioner had not questioned the competence of Parliament in enacting the law and said the petitioner challenged it only on the ground of harshness.

“The questions (asked by the petitioner) may require an authoritative answer... The peculiar situation in which the case arises and the grounds on which the provisions of Section 364A are assailed persuade us to the view that this case ought to go before a larger bench of three judges for hearing and disposal.”

Rich-poor divide

The Times of India, Jul 21 2015

Pradeep Thakur & Himanshi Dhawan

Here's proof that poor get gallows, rich mostly escape

Disadvantaged often can't pay for good lawyers

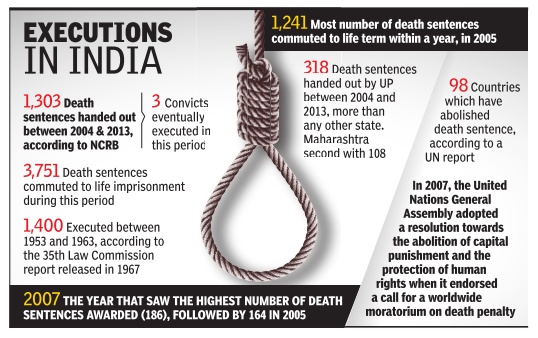

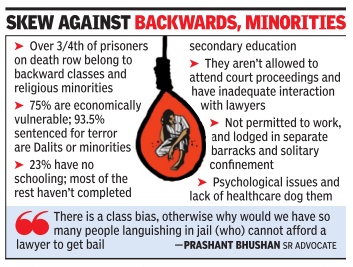

The fact that our legal system is skewed against the poor and marginalized is well known. And to that extent, it's only expected that they get harsher punishment than the rich. But here are figures that tell the full story. A first of its kind study , which has analysed data from interviews with 373 death row convicts over a 15-year period, has found three-fourths of those given the death penalty belonged to backward classes and religious minorities; an equal proportion were from economically weaker sections. The reason why the poor, Dalits and those from the backward castes get a rougher treatment from our courts is more often than not their inability to find a com petent lawyer to contest their conviction. As many as 93.5% of those sentenced to death for terror offences are Dalits or religious minorities.

The findings are part of a study conducted by National Law University students with the help of Law Commission that is engaged in a wider consultation with different stakeholders on the issue of death penalty and whether it should be abolished. Law panel chairman Justice A P Shah, himself a strong proponent of abo lition of death penalty , is to submit a final report to the Supreme Court by next month.

Senior advocate Prashant Bhushan said: “It is true that there is a class bias, otherwise why would we have so many people languishing in jail because they cannot afford a lawyer to get bail?“ He said only 1% of the people can afford a competent lawyer. Afzal Guru hardly had any legal representation at the trial court stage, he added.

Founder of Human Rights Law Network and senior advocate Colin Gonsalves says, “I think the finding that 75% of the death row convicts are poor is the absolute minimum. The rich mostly get away while the very poor, especially Dalits and tribals, get the short shrift.“

The NLU students have interviewed all the death sentence convicts and have documented their socio-economic background. The psychological torture these prisoners face before they are hanged are some of the observations in the study . Prisoners on death row are not allowed to attend court proceedings most of the time.

Arbitrary imposition of death penalty

The Times of India, Jul 21 2015

Pradeep Thakur & Himanshi Dhawan

Death penalty cannot be arbitrarily imposed: Expert

Of the over 1,600 convicts awarded the death penalty in the last 15 years, the Supreme Court confirmed the sentence in only 5% of cases while the rest were either acquitted or the sentence commuted to life. A recent study by the National Law University that has researched death row convicts since 2000 has found that of the 1,617 prisoners sentenced to death by trial courts, the punishment was confirmed in only 71 cases. While 22 convicts were acquitted, in the case of 115, it was commuted to life.No wonder voices against the death penalty are growing.Roger Hood, professor of criminology at Oxford University and a renowned advocate of abolition of death penalty , has told the Law Commission in a consultation that “capital punishment is not an option for India as there were very few convictions, and most were wrong“.

Hood has said India is violating Article 6(1) of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the UN human rights charter, according to which `no death penalty can be arbitrarily imposed'. An opportunity of reformation after long retention must be given to the accused which is one of the rights according to ICCPR, he said. “Failure to provide judicial support may lead to crimes but there is no proof that death penalty helped in deterring crimes,“ Hood said. He was invited by the Law Commission last week for a consultation on capital punishment.Legal experts, social thinkers and politicians were part of the day-long deliberations in the capital on July 11.

Making a strong case for abolition of death penalty , Law Commission chairman Justice A P Shah said about two-thirds of the world has abolished death penalty and “it is time we revisited our stand“. There were six politicians who were part of the consultation process, in cluding Varun Gandhi of BJP, Kanimozhi of DMK Shashi Tharoor and Manish Tewari of Congress, who advocated abolition of death penalty.

Wajahat Habibullah, ex chief of National Commission for Minorities, said he had personal confrontation with terrorism, and still felt that death penalty was not the way to deal with terrorism. “We won the Independence struggle through the principles of `ahimsa', so we must follow it also,“ he said.

Senior advocate Prashant Bhushan blamed the trial courts for arbitrary and irresponsible judgments on death sentences. “Death penalty is a form of retribution and violence by the state. It promotes a lynch mob mentality and is not a significant deterrent for people. There is always a chance that the judicial system might go wrong,“ he said.

Suhas Chakma of the Asian Centre for Human Rights blamed executions by the state as `politically motivated'. “The fact that few sentences have been confirmed by the high courts and even fewer by the Supreme Court in comparison to the number of cases reported in the NCRB, shows that death penalty has no impact and it has no use,“ he said.

Who should debate death penalty: SC or Parliament?

The Times of India, Aug 03 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

For the past many decades, we have witnessed a psychological and constitutional battle between two classes -those seeking abolition of death penalty and others who lean for its retention. Yakub Abdul Razak Memon's last-gasp attempts to seek stay of his execution has brought the spotlight back on the debate between abolitionists and retentionists.

Petitions to save Yakub from the gallows assumed a Phoenix-like character as the execution time approached.Dismissal of one was quickly followed by another. Such is the importance given to right to life by the Supreme Court that it opened its doors postmidnight and heard Yakub's plea till the crack of dawn.

The rejection of his final appeal drew the ire of activistlawyers who had virtually taken the legal battle as an all-out war against retentionists.

Their sombre mood soon turned combative. Many renowned advocates who have doggedly fought for human rights for years sniped at the justice delivery system and government, saying a “lynch mob“ and “bloodlust“ attitude had resulted in a “tragic mistake by the SC“.

Till 1973, the law had given absolute discretion to the judges to choose between death penalty and life imprisonment in murder cases. Despite this, the SC had repeat edly cautioned the trial courts to exercise discretion, keeping in mind the criminal and not the crime.

In 1973, the new Criminal Procedure Code made it imperative that life imprisonment was the rule and death penalty the exception for murder convicts. It also said the judge was duty-bound to record special reasons for which heshe preferred to award death penalty instead of life term.

The analysis of `special reason' led the SC to devise the `rarest of rare' doctrine for award of death penalty in the Bachan Singh case in 1982 while upholding the validity of capital punishment. This we will deal with a little later.

Even prior to the enactment of the new CrPC, a five judge SC bench in Jagmohan Singh vs state of UP (1973 AIR 947) had answered alleged arbitrariness in imposing death penalty , which the petitioner said extinguished every constitutional right of a convict, and that there was no guideline for judges in deciding which cases warranted imposition of capital sentence.

It had said, “The exercise of judicial discretion on well-recognized principles is, in the final analysis, the safest possible safeguard for accused.“

Seven years later, a threejudge bench headed by Justice V R Krishna Iyer dealt with a similar question in Rajendra Prasad vs State of UP (1979 AIR 916). It had cautioned against individual cases being made examples to argue either for abolition or retention.

“Personal story of an actor in a shocking murder, if considered, may bring tears and soften the sentence. He might have been a tortured child, an ill-treated orphan, a jobless man or the convict's poverty might be responsible for the crime,“ it had said.

However, it upheld the constitutional validity of death penalty saying there could be a situation where law-breakers brutally kill law enforcers trying to discharge their function. “If they are killed by designers of murder and the law does not ex press its strong condemnation in extreme penalization, justice to those called upon to defend justice may fail. This facet of social justice also may in certain circumstances and at certain stages of societal life demand death sentence.“

Four years later, a constitution bench by four-to-one majority upheld the validity of death penalty in Bachan Singh case on August 16, 1982. It had classified murders into two broad categories -one committed purely for private reasons and the other which “unleash a tidal wave of such intensity , gravity and magnitude, that its impact throws out of gear the even flow of life“.

It explained the stand of abolitionists. “Statistical attempts to assess the true peno logical value of capital punishment remain inconclusive.Firstly , statistics of deterred potential murderers are hard to obtain. Secondly , the approach adopted by the abolitionists is over simplified at the cost of other relevant but imponderable factors, the appreciation of which is essential to assess the true penological value of capital punishment. The number of such factors is infinitude, their character variable, duration transient and abstract formulation difficult,“ it had said.

However, it had sounded caution. “Judges should never be blood-thirsty . Hanging of murderers has never been too good for them. Facts and figures, albeit incomplete, furnished by the Union of In dia, show that in the past, courts have inflicted the extreme penalty with extreme infrequency -a fact which attests to the caution and compassion they have always brought to bear on the exercise of their discretion.“

The statistics and studies in the past few decades have been woefully inadequate to help the SC arrive at a definitive opinion about the efficacy of death penalty. It is time for abolitionists to spend their energies convincing representatives of people to raise the matter in Parliament and bring an amendment to the provisions of law providing for death penalty rather than blame the judiciary for imposing the punishment in `rarest of rare' murder cases.