Chamar

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Chamar

The tanner caste of Behar and Upper India, found also in all parts of Bengal as tanners and workers Traditions of odgin. in leather under the name Chamar or Charmakar. Aocording to the PUl'Cl.nas, the Chamars are desoended from a boatman and a Chandal woman; but if we are to identify them with the K,havara or leather-worker mentioned in the tenth chapter of Manu, the father of the caste was a Nisbada and the mother a Vaideha. The NisMda, again, is said to be the offspring of a Brahman and a Sudra mother, and the Vaideha of a Vaisya father and Brahman mother. In one place, indeed, Mr. Sherring seems to take this mythical genealogy seriously, and argues that the "rigidity and exolusiveness of caste prejudioes among the Chamars are highly favourable to the supposition" that Manu's acoount of them is the true one, and oonsequently that the Chamars being "one-half of Brahmanioal, one-fourth of Vaisya, and one-fourth of Sudra descent," may" hold up their beads boldly in the presence of the superior castes." Stated in this form, the argument verges on the grotesque; but it appears from other passages that Mr. Sherring was strongly impressed with the high-caste appearance of the ChamaI' caste, and thought it possible that in this particular instanoe the traditional pedigree might oontain an element of historical truth.

Similar testimony to the good looks of the Chamars in oertain parts of India oomes to us from the Central Provinces, where they are said to be lighter in oolour than the members of other oultivating castes, while some of tl?-e men and many of the women are remarkably handsome. In Eastern Bengal, again, Dr. Wise describes the caste as less swarthy than the average Chandal, and infinitely fairer, with a more delioate and intelleotual oast of features than many Srotriya Brahmans. On the other hand, Sir Henry umiot, writing of the North-West Provinces, says :-" Chamars are reputed to be a dark race, and a fair Chamar is said to be as rare an object as a black Brahman. .

Karia Brahman gor Chamar Inke sath na uta1'iye par', that is, do not cross a river in the same boat with a black Brahman or a fair ChamaI'; both objects being considered of evil omen." Mr. Nesfield thinks the Chamar "may have sprung out of several different tribes, like the Dom, Kanjar, Rabura Cheru, eto., the last remains of whom are still outside the pale of hiudu socicty.

Originally he appears to have been an impressed labourer or oegcil', who was made to hold the plough for his master and received in return space for building his mud hovel near the village, a fixed allowance of grain for every working day, the free use of wood and grass on the village lands, and the skins and bodies of all the animals that died. This is very much the status of the ChamaI' at the present day. He is still the field slave, the grass-cutter, the remover of dead animals, the hide-skinner, and the carrion-eater of the Indian village." L astly, it should be observed that Mr. Hewitt, whose report on the settlement of the Raipur district is the toCU!; classicus for the Chamars of the Central Provinces, clearly regards them as to some extent an exceptional type, and lays stress on the fact that they do not present the same degraded appearance as their brethren in other parts of India.

Chamars trace their own pedigree to Ravi 01' RUI Das, the famous disciple of Ramananda at the end of the fourteenth century, and whenever a Chamar is asked what he is, he replies a Ravi Das. Another tradition current among them alleges that their original ancestor was the youngest of four Brahman brethren who went to bathe in a river and found a cow struggling in a quicksand. They sent the youngest brother in to rescue the animal, but before he could get to the spot it had been drowned. He was oompelled therefore by his brothers to remove the carcass, and after he had done this they turned him out of their caste and gave him the name of Chamar.

Looking at the evidence as a whole, and allowing that there are points in it which seem to favour the conjecture that the Chamars may be in part a degraded section of a higher race, I do not consi¬der these indications clear enough to override the presumption that a caste engaged in a filthy and menial occupation must on the whole have been recruited from among the non-Aryan races. It may be urged, indeed, that the early Aryans were well acquainted with the use of leather, and were free from those prejudices which lead the modern Hindu to condemn the art of the tanner as unclean. The degradation of the OMrmamna of Vedic times into the outcaste ChamaI' of to-day may thus have been a slow process, carried out gradually as Brahmanical ideas gained strength, and the 'fair ChamaI" whom the proverb warns men to beware of may be simply an instance of reversion to an earlier Aryan type, which at one time formed an appreciable proportion of the caste. All this, however, is pure conjecture, and counts for little in face of the fact that the average ChamaI' is hardly distinguishable in point of features, stature, and complexio!l from the members of those non-Aryan races from whose ranks we should prima jaf:ie expect the profession of leather-dresser to be filled. Occasional deviations from this standard type may be due either to licti~ons with members of the higher castes or to some cause which cannot now be traced.

Internal structure

Like all large castes, the Chamars are broken up into a number of endogamous groups. These are shown in Inwl'nn structure. Appendix I, but I am doubtful whether tho ennmoration is complete. The Dhusia sub-caste alone appears to have exogamous divisions of the territorial or local tYI!(~, while in the other sub-castes marriages are regulated by the usual formula for reckoning prohibited degrees calculated to seven generations in the descending line. Chamars profess to marry their daughters as infants; but in practice the age at which a girl is married depends mainly upon the ability of her parents to defray the expenses of the wedding, and no social penalty is inflicted upon a man who allows his daughter to grow up unmarried. Polygamy is permitted, and no limit appears to be set to the number of wi ve8 a man may have.

Marriage

Like the Doms, and unlike most other castes, Chamars forbid the marriage of two sisters to the same husband. In the marriage ceremony an elder of the caste presides, but a Brahman is usually consulted to fix an auspicious day for the event. The father of the bride receives a sum of money for his daughter, but this is usually insufficient to meet the expenses of the wedding. During the man-iage service the bridegroom sits on the knee of the bride's father, and the bridegroom's father receives a few ornaments and a cup of spirits, after which each of the guests is offered a cup. No manoa 0 1' wedding bower is made, but a barber prepares and whitewashes a space (clv11lk), within which the couple sit. He also stains the feet of the bride and brideO'room with cotton soaked in lac dye (alta), and is responsible that all the relatives and friends are invited to the marriage. The caste elder, who officiates as priest, binds mango leaves on the wrists of the wedded pair, and chants man(;ras or mystic verses; while the bridegroom performs silldu1"dan by smearing vermilion on the bride's forehead and the parting of her hair.

This is deemed the valid and binding portion of the ceremony. Widows are permitted to marry again. Usually when an elder brother dies childless the younger brother must marry the widow within a year or eighteen months, unless they mutually agree not to do so, in which case sho returns to her father's house, where sho is free to remarry with any one. If there are children by the first marriage, it is deemed the more incumbent on the widow to marry the younger brother; but even in this (Jase she is not compelled to do so. the custody of the children, however, remains with their paternal uncle, and the widow forfeits all claim to share in her late husband's estate. On her remarriage the family of her first husband cannot claim any compensation for the bride-price which they paid for her on her marriage. Belm'e a widow marries again her relatives go tbrough the form of consulting the panchayat, with the object, it is said, of deciding whether the marriage is well-timed or not. Divorce is permitted with the sanction of the panchayat of the caste. Divoroed wives may marry again.

Religion in Bengal

By far the most interesting features of the ChamaI' caste, says Dr. Wise, are their religious and social customs. They have no purohit j their religious cere¬monies, like those of the Doms, being directed by one of the elders of the caste. But gurus, who givo mantras to children, are found, and a Hindustani Brahman is often consulted regarding a lucky day for a wedding. Chamcl.rs havc always cxhibited a remarkable dislike to Brahmans and to the Hindu ritual. They nevertheless observe many rites popularly supposed to be of Hindu origin, but which are more probably survivals of the worship paid to the village gods for ages before the Aryan invasion. The large majority of Bengali Chamars profess the deistic Sri-Narayani creed. Sants, or professed devotees, are common among them, and the Mahant of that sect is always regarded as the religious head of the whole tribe. A few Dacca Chamars belong to the Kabir-Panth, but none have joined any of the Vaishnava sects.

Festivals

The principal annual festival of the Chamars is the Srlpanchaml, celebrated on the fifth day of the lunar month (If Magh (January-February), when they abstain from work for two days, spending them in alternate devotion at the DMmghar, or conventicle of the Sri-N arayani sect, ann in intoxica-tion at home. the DMmghar is usually a thatched house consisting of one large room with verandahs on all sides. At one end is a raised earthen platform, on which the open Grantha1 garlanderl with flowers is laid, and before this each clisciple makes obeisance as he enters. The congregation squats all round the room, the women in one corner, listening to a few musicians chanting religious hymns and smoking tobacco and ganja, indifferent to the heat, smoke, and stench of the crowded room. The Mahant, escorted by the Sants carrying their parwanas or certificates of membership, enters about 1 A.lIf., when the service begins. It is of the simplest form. The Mahant, after reading a few sentences in Nagari, unintelligible to most 'of his hearers, receives offerings of money and fruit. The congregation then disperses, but the majority seat themselves in the verandahs and drink spirits. If the physical endurance of the worshippers be not exhausted, similar services are held for several successive nights, but the onlinary one only lasts two nights.

On the" Nauami," or ninth lunar day of Xswin (September-October), the day preceding the Dasbara, the worship of Devl is observed, and offerings of swine, goats, and spirits made to the dread goddess. On this day the old Dravidian system of demonolatry, or Shamanism, is exhibited, when one of their number, working himself up into a frenzy, becomes possessed by the demon and reveals futurity. The Chamars place great value on the answers given, and very few are so contented with their lot in life as not to desITe an insight into the future. A few days before the Dashara the OMmains perambulate the streets, playing and singing, with

1 The Grantha or scriptm'cs of the Sri.Narayani or Siva.Narayani sect are believed by them to have existed for oleven hundred and forty.five years, but to have been unintelligible until Sitala, an inspired Sannyisi, translated it in com-pliance with a divine command. The translation, consisting of several works in the Devanagari character, is the undoubted composition of the Rajput Siyanarayana of Ghazipur, who wrote it about A.D. 1735. The most important of these works are the Guru.nyasa and Santa•vilasa.

The former, compiled from the Pm'ana , gives an account of the ten Avatlus of Vishnu, or Narayana, and is subdivided into fourteen chapters, of which the first six treat of the author, of faith, of the punishment of sinner, of virtue, of a future state, and of discipline. The latter is a treatise on moral sentiments. The opening lines are,-" The love of God, and His kuowledge is the only true understanding." a pot of water in the left hand: a sp~'ig of nim in the righ.t, soliciting alms for the approaching Devi festival. Money or gram must be got by begging, for they ~elieve the worship woul~ be ~effect~al if the offerings had to be paId for, Another of theIr festivals IS the Ramanauami, or birth-day of Rama, held on the ninth lunar day of Chaitra (March-April), when they offer flowers, hetel-nut, and sweetmeats to their ancestor, Ravi Das.

When sickness or epidemic diseases invade tJheir homes, the women fasten a piece of plantain leaf round their necks and go about begO'ing. Should their wishes be fulfilled, a vow is taken to celebrate the worship of Devi, Sltala, or Jalka DevI, whichever goddess is suppo~ed to cause the outhreak. the worship is held on a piece of ground marked off and smeared with cowdung. A fire being lighted, and ghi and spirits thrown on it, the worshipper makes obeisance, bowing his forehead to the ground and muttering certain incantations. A swine is then sacrificed, and the bones and offal being buried, the flesh is rcasted and eaten, but no one must take home with him any scrap of the victim. J alka DevI seems identical with the Rakshya Rail of Bengali villagers, and is said to have seven sisters, who are worshipped on special occasions.

Religion in Behar

The Chamars of Behar are more orthodox in matters of Religion than their brethren of Eastern Bengal, and Religion m Bohar. appear to conform in the main to the popular Hinduism practised by their neighbours. Some of them indeed have advanced so far in this direction as to employ Maithil Brahmans for the worship of the regular Hindu gods, while others content themselves with priests of their own caste. In the Santal Parganas such priests go by the name of p2wi, and the story is that they are Ranaujia Brahmans, who were somehow degraded to be Chamars. Lokesari, Rakat Mala, Mansaram, Lala, Karu Dana, Masna, Mamia, and Jalpait are the special minor gods of the caste, but Bandi, Goraiya, and Kali are also held in reverence. Some hold tha.t Ravi Das ranks highest of all, but he seems to be looked upon as a sort of deity, and not as the preacher of a deistic Religion. The offerings to all of these gods consist of sheep, goats, milk, fruit, and sweetmeats. of which the members of the household afterwards partake. Accord¬ing to Mr. N esfield, the caste also worship the "api, or tanner's knife, at the Diwali festival. It is a curious circumstance, illustrating the queer reputation borne by the Chamars, that throughout Hindustan parents frighten naughty children by telling them that Nona Ohamain will carry them off. This redoubtable old witoh is said by the Chamars to have been the mother or grandmother of Ravl Das; but why she aoquired suoh unenviable notoriety is unknown. In Bengal her name is never heard of, but a domestic bogey haunts each household. In one it is the Burhf, or old woman; in another, Bhlita, a ghost; in a third, Pretni, a witch; and in a fourth, Gala-Kata Rafir, literally, the 'infidel with his throat gashed.'

Funerals

In Behar the dead are burned in the ordinary fashion, and Funerals. srciddh performed on the tenth or, acoording to some, the thirteenth day after death. Libations of water (tm'pan) and balts of rice (pinda) are offered to the spirit of anccstors in general in the month or Xswin. In Eastern Bengal Chamars usually bury their dead, and if the husband is buried his widew will be laid beside him if she had been taught the same mantra, otherwise her bocl.y is burned. Sants of the Sri-Narayani sect are objects of special reverence, and whenever one dies in a strange place thc Sants on the spot subscribe and bury him. The funeral procession is impressive, but very noisy. The corpse, wrapped in a sheet with a roll of cloth wound round the head, is deposited on a covered litter. Red flags flutter from the four corners, ond a white cloth acts as a pall. With discordant music the body is carried to the grave, dug in some waste place, where it is laid flat, not sitting, as with the Jugis.

Social status

By virtue of his occupation, his habits, and his traditional desrent, the Ohamar stands condemned to rank at the very bottom of the Hindu social system and even the non-Aryan tribes who haye of recent years sought ndmission into the Hindu communion are speedily promoted over his head. His ideas on the subject of diet are in keeping with his degraded position. He eats beef, pork, and fowls, all unclean to the average IIindu, and, like the gypsies of' Europe, has no repugnance to cooking the flesh of animals which have died a natural death. Some say that they only eat cattle which have died a natural death, but this may be merely a device to avert the suspicion of killing cattle by poison, which natul'3.11y attaches to people who deal in hides and horns. Dospised, however, as he is by all classes of orthodox Hindus, the Ohamar is proud and punctilious on certain special points, never touching the leavings of a Brahman's meal, nor eating anything cooked by a Bengali Brahman, though he has no objection to take food -from a Brahman of Hindustan.

Chamars are, says Dr. Wise, inconceivably dirty in their habits, and offend others besides the Hindu by their neglect of all sanitary laws. Large droves of pigs are bred by them, and it is no uncommon sight to witness children and pigs wallowing together in the mire. IIides in various stages of prepamtion hang about their huts, yet, strange to say, the women are very prolific, and, except in a fisher settlement, nowhere are so many hcalthy-Iooking children to be seen as in a filthy Oham~r village. Mr. 13eames, however, mentions in a note to his edition of Sir llenry Elliot's Glossary that Chamars, from their dirty habits, are peculiarly liable to leprosy, and that the name of the Kori or Korhi sub-caste probably refers to this fact.

Occupation

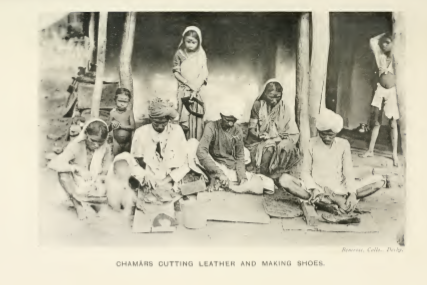

Chamars are employed in tanning leather, making shoes and saddlery, and grooming horses. In Eastern eng a t e amrd-aros hll'e them to pre¬serve hides, but there is such bitter enmity between them and the allied caste of Muchi or RishI, that tbcy are rarely engaged to skin animals. lest the perquisites of the latter group should seem to have been interrered with. To some extent the distinotions between the variolls s\lb-ca~tes ~eem to be based upon clifferences of ocoupation. Thus.the Dhusla sub-caste adhere to the original occupation of leather¬dresslDg, and also mako shoes and servo as musicians at weddin'" and othor domestic fcstivitios, their favo1.U'ite instruments being the elltOt or drum, the cymbals (fha.njh), thc ha p (ektara), and the tambourinc (kha1?ja?'i).

Most of these oocupations are also followed by the DMrh, who besides carry palanquins and eat the fl.e~h of animals that have died a natural death, except only the horse. The Guria are cultivators; some few holding ocoupancy rights, and others being landless day-labourers, who wander about and work for hire at harvest time. The Jaiswara work as syces; the Dohar are cobblers, using only leather string, and not cotton thread, to mend rents; the Sikharia are cultivators and shoemakers; the Ohamar Tanti work as weavers, and will not touch oarrion; and the Sarlci, many of whom have emigrated from Nepal into Ohumparan, are both butchers and hide-dl'essers. Some Chamars burn lime, but this oocupation has not beoome the badge of a sub-caste, though those who follow it call themselves Ohunibara. In Behar the Ohamar is a village functionary like the Ohaukidar or Gora.it. He holds a small portion of village land, and is invariably called to po t up official notioes, and to go round with his drum proclaiming public announcements.

'The Ohamains, or female Chamars, says Dr. Wise, are distin¬ guished throughout Bengal by their huge inelegant anklets (paid,) aud brAcelets (bang'I'i), made of bell-metal. 1'he lormer often weigh from eight to ten pounds, the latter from two to four, and both closely resemble the corresponding ornaments worn by Sant,U women . They also wear the tikli, or spanglc, on the forehead, although in Bengal it is regarded as a tawdry ornament of the lowest aud most immoral women. Ohamalns consider it a great attraction to have their bodies tattooed; consequently their chests, foreheads, arms, and legs are disfigured with patterns of fantastic shape, In Rindu¬ stan the Natn! is the great tattooer; but as members of this caste are seldom met with in l£astern Bengal, the ObamMns are often put to great straits, being frequently obliged to pay a visit to their original homes for the purpose of having the fashionable decoration indelibly stained on their bodies.

Ohamar women are cercmonially unclean for ten days sub¬ sequent to chilJbirth, when after bathing, casting away all old cookillg utensils, and buying new ones, a feast, called Bal'lIII i.lla , is celebrated, upon which she resumes her usual householU duties. They still observe the pleasing custom of BluiipltOta on the last day of the Hindu year, when sisters present theu' brothers with a new suit of clothes and sweetmeats, and make with a paste of red sandal wood a dot on their foreheads; a similar usage, known as Blmitri¬ dvitiya, is practised by Bengalis on the second day after the new moon of Kartik.

Chamars are the midwives of India, and are generally believed, though erroneously, to be skilled in all the mysteries of parturition. They have no scruples about cutting the navel string, as other Hindus have; but in the villages of the interior, where no Ohamalns reside, the females of the Bhltinmall, Ohandal, and Ghulam Kayath ca tes act as midwives, and are equally unscrupulous. It is a pro¬ verbial saying among Hindns that a household becomes unclean if a Ohamar w()man has not attended at the biJ:th of any child belonging to it.

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Chamars in 1872 and 1881. The figures of the former year includo, and those of the latter exclude, the Muchis in Bengal Proper.

Notes

This Hindustani tribe is found in all parts of Bengal, living apart in villages of their own, everywhere following the same customs, and prosecuting the same trade. The north-west provinces is the home of the Chamar, and in 1865 they numbered 3,580,385 individuals. In Bihar, again, according to the cunsus of 1872, there were 711,721, while in Bengal proper, Chamars and Rishis only numbered 393,490. In the nine eastern districts 47,053 were returned, of whom 24,063, or 50.6 per cent., belonged to Dacca.

1 "Hindu Tribes and Castes," pp.346, 390.

2 "Notes on Inferior Castes, &c, in the N.W. Provinces," by E.A. Reade, C.S. p. 39.

The Chamar is descended, according to the Puranas, from a boatman and a Chandal woman; but Menu represents them as being Nishada, or outcasts, the offspring of a Brahman and a Sudra mother. In Oudh, at the present day, their descent is traced to the fabulous hero Nikhad and a Dab-gar, or currier woman.1 There cannot, however, be any doubt that Chamars belong to a semi-Hinduised aboriginal tribe reduced to the level of other helot races, and expelled from the homes of the Aryan Hindus.

The Chamar is proverbially a black man, but in the Central provinces he is described as a brown, not a dark skinned person, while in Eastern Bengal he is not so swarthy as the average Chandal, and is infinitely fairer, with a more delicate and intellectual cast of features, than many Srotriya Brahmans.

Chamars trace their own pedigree to Ravi, or Rai, Das, the famous disciple of Ramananda at the end of the fourteenth century, and whenever a Chamar is asked what he is, he replies a Ravi Das. Though despised and spurned by all classes, the Chamar is proud and punctilious, never touching the leavings of a Brahman's meal, nor eating anything cooked by a Bengali Brahman, although he has no objections if a Hindustani Brahman prepares it.

According to the Chamars of Eastern Bengal, the caste has the following seven "gots" or subdivisions:�

In Dacca the Chamars all belong to the Jhusia "got" and came originally from Ghazipur, Mungir, and Arrah.. Many have permanently settled in Bengal, but others only remain a few years until money is saved, when they return to spend it at their homes. Chamars are very gregarious, being generally massed in the large towns, but occasionally small settlements are found scattered throughout the interior.

In Dacca, Chamars are employed in tanning leather, making shoes, and grooming horses. The Chamra-farosh hire them to preserve hides, but there is such bitter enmity between the caste and the Rishis, that they are rarely engaged to skin animals.

The Chamar is inconceivably dirty in his habits, and offends others besides the Hindu by his neglect of all sanitary laws. Large droves of pigs are bred by them, and it is no Uncommon sight to witness children and pigs wallowing together in the mire. Hides, in various stages of preparation, hang about the hut, yet strange to say the women are very prolific, and with the exception of a fisher village, nowhere are so many chubby children to be seen as in a filthy Chamar hamlet. Chamars eat both beef and pork, and like the European gypsies have no repugnance to cooking the flesh of animals dying naturally.

Hindustani Chamars are always employed as musicians at Hindu weddings, their favourite instruments being the "Surnae," or pipe, and varieties of the drum, such as "Dholak" and "Tasa," but in Eastern Bengal no male or female Chamar ever performs as a professional musician, and it is only at domestic festivities that they play on the "Dhol," or drum; the "Jhanjh," or cymbals; the "Ektara," or harp; and the "Khanjari," or tambourine.

By far the most interesting features of the Chamar caste are their religious and social customs. They have no Purohit, their religious ceremonies being directed by one of the elders; but Gurus, who give Mantras to children, are found, and a Hindustani Brahman is often consulted regarding a lucky day for a wedding. Chamars have always exhibited a remarkable dislike to Brahmans, and to the Hindu ritual. They, neverthelesss, observe many rites popularly regarded as of Hindu origin, but which were probably festivals of the village gods kept for ages before the Aryan invasion. The large majority of Bengali Chamars belong to the Sat Narayana sect, and "Sants" are very numerous among them. Furthermore, the Mahant of that sect is always regarded as the religious head of the whole tribe.

In Bilaspur of the central provinces, Chamars constitute twenty-seven per cent. of the Hindu population, and in 1825 one of their number, named Ghasi Das, founded a religion which he called Sat-nami. The principal doctrines of his creed were social equality, no idolatry, and the worship of one God, who was not to be represented by any graven-image or likeness. Ghasi Das died in 1850, but his work still lives. Though imbued with many superstitions, the Chamars have generally adopted this new faith, repudiated Brahmanical interference, and enlisted many brethren of other districts into their ranks. The Sat-Narayana sect is also a deistical one, and it is a curious coincidence, that the tribe should have adopted, in places so far apart, a creed that is almost identical.

A few Dacca Chamars belong to the Kabir "Panth," but none have joined any of the Vaishnava sects.

The principal annual festival of the Chamars is the Sri-panchami, when they abstain from work for two days, spending them in alternate devotion at the Dhamghar, and in intoxication at home. Another of their festivals is the Ramanauami, or birthday of Rama, held on the ninth lunar day of Chaitra (March-April), when they offer flowers, betle-nut, and sweet-meats to their ancestor, Ravi Das.

A few days before the Dashara the Chamains perambulate the streets, playing and singing, with a pot of water in the left hand, a sprig of "Nim" in the right, soliciting alms for the approaching Devi festival. Money, or grain, must be got by begging, for they believe the worship would be ineffectual if the offerings had to be paid for.

On the "Nauami," or ninth lunar day of Aswin (September-October), the day preceding the Dashara, the worship of Devi is observed, and offerings of swine, goats, and spirits, made to the dread goddess. On this day the old Dravidian system of demonolatry, Shamanism, is exhibited, when one of their numbed working himself up into a frenzy, becomes possessed by the demon and reveals futurity. The Chamars place great value on the answers given, and very few are so contented with their lot in life as not to desire an insight into the future.

When sickness, or epidemic diseases, invade their homes the women fasten a piece of plantain leaf round their necks, and go about begging. Should their wishes be fulfilled, a vow is taken to celebrate the worship of Devi, Sitala, or Jalka Devi, whichever goddess is supposed to cause the outbreak.

The worship is held on a piece of ground marked off, and smeared with cow-dung. A fire being lighted, and "Ghi" and spirits thrown on it, the worshipper makes obeisance, bowing his forehead to the ground, and muttering certain incantations. A swine is then sacrificed, and the bones and offal being buried, the flesh is roasted and eaten, but no one must take home with him any scrap of the victim.

Jalka Devi seems identical with the Rakhya Kali of Bengali villagers, and is said to have seven sisters who are worshipped on special occaasions.

At Chamar marriages an elder presides, but a Brahman usually selects the day. The father of the bride, as a rule, receives a sum of money for his daughter. During the marriage service the bridegroom sits on the knee of the bride's father, and the bridegroom's father receives a few ornaments and a cup of spirits, after which each of the guests is offered a cup.

A "Marocha" is not made, but a Hindustani barber prepares and whitewashes a space, or "Chauk," within which the pair sit. He also stains the feet of the bride and bridegroom with "Alta," or cotton soaked in lac dye, and is responsible that all the relatives and friends are invited to the marriage.

Chamars have no ceremony at the naming of a child, the name being selected by a relative or intimate friend.

The only class of natives, not Muhammadans, who still practise the Sagai, or Levirate marriage, are the Chamars. When an elder brother dies childless, the younger must marry the widow after a year, or eighteen months, unless they mutually agree not to do so, in which case she returns to her fathers house, where she is free to remarry with anyone she pleases.

On her remarriage, the family of her first huuband cannot claim any compensation, as is the custom with the Jews and other races, who follow this marriage law. When a younger brother marries his widowed sister-in-law, no service is performed.

The formality is gone through of consulting the Panchait, with the object of deciding whether the marriage is well-timed or not. An elder brother, again, is prohibited from marrying his younger brother's widow, the sole purpose of the Levirate marriage being the perpetuation and exaltation of the head of the family. Among Muhammadans the Levirate marriage is ordained but rarely performed. According to their legislators the sister-in-law must live for a whole year as a widow, when she may become the "Nikah" wife of her husband's brother, for that is the only position she can aspire to. Chamars do not consider concubinage (Ardhi) disgraceful, but being usually poor, few can afford themselves the luxury.

Chamars still observe the pleasing custom called "Bhai-phota," on the last day of the Hindu year, when sisters present their brothers with a new suit of clothes and sweetmeats, and make with a paste of red sandal wood a dot on their foreheads; a similar usage, known as "Bhratri-dvitiya," is practised by Bengalis on the second day after the new moon of Kartik.

Chamars usually bury their dead, and if the husband is buried, his widow will be laid beside him if she had been taught the same Mantra, otherwise her body is burned.

Throughout Hindustan parents frighten naughty children by telling them that Nona Chamain will carry them off. This redoubtable old witch is said by the Chamars to have been the mother, or grandmother, of Ravi Das, but why she acquired such unenviable notoriety is unknown. In Bengal her name is never heard of, but a domestic bogey haunts each household. In one it is the "Burhi," or old woman, in another, "Bhuta," a ghost, in a third, "Pretni," a witch, and in a fourth, "Gala-Kata Kafir," literally, the infidel with his throat gashed.

The Chamains, or female Chamars, are distinguished throughout Bengal by their huge inelegant anklets (Pairi) and bracelets (Bangri), made of bell-metal. The former often weigh from eight to ten pounds, the latter from two to four. They also wear the "Tikli," or spangle, on the forehead, although in Bengal it is regarded as a tawdry ornament of the lowest and most immoral women.

Chamains consider it a great attraction to have their bodies tattooed, consequently their chests, foreheads, arms, and legs, are disfigured with patterns of fantastic shape. In Hindustan the Natni is the great tattooer, but not being met with in Bengal, the Chamains are often put to great straits, being frequently obliged to pay a visit to their original homes for the purpose of having the fashionable decoration indelibly stained on their bodies.

Chamains are the midwives of India, and are generally believed, though erroneously, to be skilled in all the mysteries of parturition. They have no scruples about cutting the navel cord as other Hindus have, but in the villages of the interior where no Chamains reside, the females of the Bhuinmali, Chandal, and Ghulan Kayath act as midwives, and are equally unscrupulous. It is a proverbial saying among Hindus that a household becomes unclean if a Chamar woman has not attended at the birth of any child belonging to it.

Chamar women are ceremonially unclean for ten days subsequent to childbirth, when after bathing, casting away all old cooking utensils and buying new ones, a feast, called "Barahiya," is celebrated, upon which she resumes her usual household duties.

1 Carnegy's "Traces of Oudh," app., p. 85.

1 "Gazetteer of the Central Provinces," p. 101; "The Highlands of Central India," by Captain J. Forsyth, p. 412.