CinemaScope films in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

CinemaScope and 70mm films in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

CinemaScope films in India

Roots in the USA and the USSR

‘The Robe’ (USA, 1953/ 20th Century-Fox/ Colour) was the world’s first motion picture to be filmed in wide-screen 35mm, CinemaScope. The original trailer had Darryl F. Zanuck, Vice President, Production, 20th Century-Fox, explaining what CinemaScope was and how it worked.

In 1956, Aleksandr Ptushko (born in Lugansk, Ukraine) released Il'ia Muromets, the first Soviet film shot in stereo and for the wide-screen (SovScope).

Indian cinema got off to a very early start with this new technology, thanks to a collaboration with the USSR's Mosfilm Studios.

The 1950s

The bilingual Indo-Soviet film ‘Pardesi’ (Hindi-Urdu/ Russian/ dirs: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Vasili Pronin) was released in 1957. The film is called ‘Khozhdenie za tri morya’ in Russian and its subtitled English version is known as ‘Journey Beyond Three Seas.’ India’s first wide-screen film was in SovColor. However, even though it starred Nargis, the most successful heroine of the time, this biopic about Afanasi, a 15th century Russian explorer in India, did not get a release beyond left-leaning arthouse cinemas. T-Series has released the film on DVD. The wide-screen SovScope format is intact but only a black and white print survives.

(Till the late 1960s many A grade, big budget [e.g. Saawan ki Ghata] as well as B+ films [e.g. Spy in Rome] were shot in 35mm and colour but released several prints in black and white and 16mm for rural markets and complimentary screenings at open-air defence amphitheatres.)

In 1957 actor-director Guru Dutt purchased from 20th Century Fox the technology needed to make a CinemaScope film—Gouri, a Bengali film with him in the lead opposite his real-life wife, the singer-actress Geeta Dutt. According to a cinema historian, “By 1957, [their] marriage had run into rough weather and was on the rocks. Guru Dutt had fallen for his new leading lady Waheeda Rehman. The breaking up of [their] marriage also began having repercussions on [Geeta Dutt’s] career. To quieten things down Guru Dutt launched a film Gauri (1957).”[1] Some of the film was shot in and around Calcutta and two songs were recorded. However, Guru Dutt decided to stop making Gouri, presumably because of the domestic situation. He launched Kaagaz ke Phool instead, with Waheeda Rehman.

‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’ (Hindi-Urdu, 1959) was India’s second CinemaScope film and was filmed in black and white, in technical collaboration with 20th Century Fox. It had an aspect ratio of 2.35: 1. This film was widely released, got excellent reviews from the minuscule literati--and scathing ones from vastly more influential bimbos like Babubhai Patel. Its soundtrack album was a success (and, like the film itself, a cult favourite to this day). However, ‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’ flopped at the box office, because the subject was considered too heady (and, to quote Dutt's friend Dev Anand, depressing) for the 1950s.

CinemaScope,thus, had a very shaky start in India.

The 1960s

Initially, CinemaScope was an expensive technology. Only such Indian cinema halls as screened English-language films (and, therefore, catered to the Indian elite) had CinemaScope projectors, lenses and widescreens. Therefore, it is a curious fact that India’s third CinemaScope film, ‘Pyar ki Pyas’ (Hindi-Urdu, 1961),which was in Gevacolour, was a low-budget family weepie. This film, too, tanked without the new screen technology getting noticed by the Indian public.

That was when the Moguls of Indian cinema stepped in. Mehboob Khan was a communist (his company’s logo was the hammer-and-sickle) who used to make the biggest budget films of the era. His ‘Aan’ (Hindi-Urdu, 1953), was the first Indian film to be shot in the extremely expensive Technicolor.(Aan was shot in 16 mm and later blown up to 35 mm.) Khan followed it up with the 172-minute, Technicolor, multi-star blockbuster ‘Mother India’ (Hindi-Urdu,1957). Therefore, it was only logical that his next film, ‘Son of India’ (Hindi-Urdu,1962) would marry the two pricey technologies to become India’s fourth CinemaScope film and the first in Technicolor.

However, ‘Son of India’ was another arthouse film and, uncharacteristically for a Mehboob Khan opus, featured only unknown actors. Once again CinemaScope failed to draw audiences. The Indian film industry gave CinemaScope one last chance. ‘Leader’ (1964) featured the biggest star of the era, was shot in Technicolor and was a mega-budget entertainer. However, the jinx surrounding CinemaScope (renamed Filmalyascope for this film) continued. If ‘Son of India’ was Mehboob Khan’s first disaster (and the last film that he ever made), ‘Leader’ was the first of a series of flops for the thitherto hyper-successful Dilip Kumar. (Incidentally, the failure of ‘Kaagaz Ke Phool’ had shattered its director Guru Dutt.)

Indian cinema gave up on CinemaScope—for the rest of the decade.

The 1970s: Hindi-Urdu cinema

Then, in 1972, came Kamal Amrohi's ‘Pakeezah’(Hindi-Urdu), which was the second biggest grosser of the year and the first Indian CinemaScope film to make money. However, its mega success was attributed to other factors and CinemaScope continued to have no takers in Hindi-Urdu cinema.

(Amrohi had always been something of an innovator. He made the offbeat Daera (1953)in which the lead pair do not so much as meet till the film's last sequence. Such lack of romance was unthinkable in Indian cinema till the 21st century. Thus, only Amrohi could have had the nerve to revive CinemaScope when the Moguls of the Indian film industry had banished it.)

South Indian (and other Indian) cinema

India’s Tamil and Telugu film industries are, on some counts, as big as the commercially better-known Hindi-Urdu cinema. Like their counterparts in Bombay (now Mumbai) they make big-budget entertainers. Filmmakers in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh were more impressed by the success of ‘Pakeezah’ and it was in South India that CinemaScope struck roots. The historical epic, ‘Rajarajacholan’ (1973) was the first CinemaScope film in Tamil,the freedom struggle blockbuster ‘Alluri Seetharama Raju’ (1974) the first CinemaScope film in Telugu , 'Sonbai ni Chundadi' (1976, dir Girish Manukant) the first in Gujarati, ‘Sose Thanda Soubhagya’ (1977) the first in Kannada , ‘Thacholi Ambu’ (1978) the first in Malayalam, ‘Hisab Nikas’ (1982, d Prashanta Nanda)the first in Odiya and 'Jeevan Surabhi' (1984/ dir: Naresh Kumar) the first in Assamese. Vairi-Jatt (1985) is arguably India’s first Punjabi language film in CinemaScope; Jaspal Bhatti’s Mahaul Theek Hai (1999) claims to be the first CinemaScope comedy in Punjabi (India). The first CinemaScope film to be made in Marathi was Dhadakebaaz (1990) by Mahesh Kothare. Hal Ta Bhaji Haloon was perhaps India’s first colour and CinemaScope Sindhi film.

By the late 1970s the majority of big-budget Tamil and Telugu films, and many in Kannada, were being made in CinemaScope.

Hindi-Urdu cinema, which had started the trend, was slow to catch on this time around.This started changing with the success of ‘Dulhan Wahi Jo Piya Man Bhaaye’ (Hindi-Urdu, 1977) a low budget CinemaScope film that was the 8th biggest hit of the year.

By the mid 1980s all big-budget films in India, and by the early 1990s all Indian films (and most South Asian films) irrespective of language, genre or budget, were being made in CinemaScope.

CinemaScope films in Bangladesh and Pakistan

East Pakistan is credited with the two major film-technology firsts of Pakistan (and, therefore, Bangladesh). Not only was East Pakistan (the present Bangladesh) more populous than the then undivided nation’s western wing, almost everyone in the East spoke Bengali, giving it a market several times as big as West Pakistan's.

West Pakistan (the present Pakistan), on the other hand, was divided into four major languages, with a fifth, Urdu, enjoying importance disproportionate to the number of its speakers. Urdu was the official language, the language that linked the five linguistic groups of undivided Pakistan and the language (wrongly) considered more sophisticated and suitable-for-literature than the other languages of at least West Pakistan.

Zahir Raihan (1935-c.1972) was an unlikely pioneer of Pakistan’s Urdu cinema. Not only was he a Bengali, he graduated with BA (Honours) in Bangla (Bengali) from the University of Dacca (now Dhaka). On the 21st February 1952 he was one of ten students who defied the ban on the now-historic Language Movement—which had since 1948 been demanding that Bangla be made one of the state languages of Pakistan. Many youths were killed on that fateful day. Zahir was sent to jail.

And yet Zahir was the maker of Pakistan’s first colour film Sangam (April 23, 1964), and also of its first (black & white) CinemaScope film Bahana (1965), both in Urdu. (The Indian magnum opus Sangam, in the making since 1962, was released a few weeks after its Pakistani namesake.)

Mala (Bengali/ 1965), also produced in erstwhile East Pakistan (by Dosani and Mustafiz), was the first film made in CinemaScope and colour in undivided Pakistan (and, thus, Bangladesh).

Lakkha (September 22, 1978) was the first CinemaScope film in Pakistan’s most widely spoken language, Punjabi. By then almost all Pakistani films were being shot in colour.

Syed Kamran Haider’s Zero Point (2012) was the first Sairaiki film in CinemaScope and Dolby Stereo.

Yousaf Khan Sher Bano (1970/ 71; writer: Ali Hyder Joshi; director: Aziz Shamim)) was the first Pashto film. Today most Pashto films are released in CinemaScope.

CinemaScope films in Nepal

Paral ko Aago (1978) was arguably the first Nepali CinemaScope film

CinemaScope films in Sri Lanka

Dr. Diego Badaturuge Nihalsinghe brought CinemaScope to Sri Lanka through Ketikathava, a short film. In 1971 he made Welikathara , the country’s first 35mm CinemaScope feature film

70mm

India

70mm cinemas screen Anglo-American films

New Delhi’s Shiela, which was inaugurated on January 12, 1961, was India’s first cinema hall capable of screening 70mm films. My Fair Lady (1964; in Delhi in 1965) was a success among elite audiences--the stereophonic sound effects of its horse racing sequence had the public asking for more stereophonic sound systems in India. Though India’s audiences for English-language cinema formed a much smaller percentage of the nation’s population in 1961 than they do in the 21st century, their numbers were sufficient to ensure that several ‘70mm halls’ were constructed in each of India’s six major metropolises in the 1960s, and at least one in every medium-sized state capital.

As early as in 1964 actress B. Saroja Devi and entrepreneur V. Ramasamy Naidu set up Central 70mm in a town as small as prosperous Coimbatore. Despite its tickets being almost twice as expensive as those of the next priciest hall, Central, which was air conditioned and housed one of India’s first ‘ice-cream-soda fountains,’ was a commercial success.

Cleopatra (70mm/ UK | USA | Switzerland) was the highest grossing film of 1963 internationally. In India it was a hit even with those who did not normally watch foreign films.

By 1964 there were a sufficiently large number of halls with 70mm projectors and widescreens in India. Therefore, several Indian producers started launching ‘70mm films.’ This really meant that around four prints would be in 70mm, and the rest in 35mm. In any case, only a few prints of even Hollywood blockbusters were in 70mm, though the percentage was somewhat higher there.

India's first 70mm film

Among the earliest ‘70mm’ films to be launched (or at least announced, with huge fanfare) around 1965 and 1966 were Alexander and Chanakya (an Indo-German co-production), Kaar Begaar (with megastar Dilip Kumar), Gold Medal (with the by then highest paid star Rajendra Kumar; it was completed in 35mm with Jeetendra) and International Crook (released only in 35mm, because of the lukewarm commercial response to the same producer’s 'Around the World').

Pachhi’s 'Around the World' (1967/ Technicolor) was the first Indian film to be actually released in the 70mm widescreen format, and also the first with a magnetic, six-track stereophonic soundtrack. It is frequently, and incorrectly, said that ‘Sholay’ (1975) was India’s first 70mm film, and the first with stereophonic sound. In this connection an inaccurate NDTV documentary is cited.<ref>"35 years on, the Sholay fire still burns". ndtv.com. Retrieved 6 December 2010.</ref> It was the second, on both counts.

'Sholay' was the biggest grosser of its era and, by some yardsticks,the most successful Indian film ever. Its success made producers with somewhat smaller budgets think of the vastly less expensive CinemaScope instead. Besides, almost all Indian theatres, including in the smallest of towns, had CinemaScope facilities by the late 1970s; only a few hundred were equipped for 70mm.

In the case of both 'Around the World' and 'Sholay' exactly four 70mm prints were released in the first instance: two were allotted to the Bombay-Maharashtra territory, and one each to Delhi and U.P. And yet both films were screened in 70mm at two cinema halls in Delhi ('ATW' at Odeon and Liberty and 'Sholay' at Plaza and Liberty). This was achieved by shuttling the 70mm print allotted to Delhi between the two halls. Over the decades 'Sholay' has acquired such a dedicated fan following that fans insist that it was India's first film in 70mm and six-track stereophonic sound, even though the film's makers have never made any such claim. All surviving prints (and DVD released by Shemaroo) of 'ATW,' on the other hand, do.

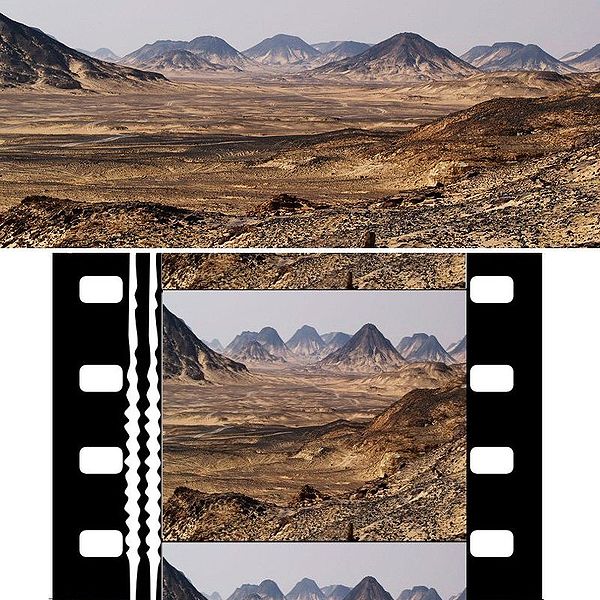

Loss of image when 35mm (normal) is blown up to 70mm or CinemaScope

Since actual 70mm (or 65mm) cameras and film were deemed too expensive at the time, both 'Around the World' and ‘Sholay’ were shot on traditional 35mm film and the 4:3 picture was subsequently blown up, cropped and matted to a 2.20:1 frame.

All Indian ‘70mm films’ after 'Around the World' and ‘Sholay’ were photographed in the 35mm CinemaScope format and blown up to 70mm. This means that the 35mm prints of both 'Around the World' and ‘Sholay’ have images at the top and bottom of the frame (and, thus, the screen) that cannot be seen in the 70mm print, because those strips have been cropped off. However, because "Padayottam,"‘The Burning Train,’ ‘Shaan’ and subsequent ‘70mm films’ were shot in CinemaScope, which has the same ‘aspect ratio,’ there was negligible loss of image.

(V. Shantaram's superhit Technicolor classical-dance [kathak] opus Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955)was re-released in 70 mm in 1982. However, by then audiences had no appetite for 143 minutes of kathak, androgynous and anonymous actors in major roles and Sanskritised dialogues. Unlike Mughal e Azam (1960), which was given a fresh lease of commercial life in 2004 by the addition of colour, CinemaScope and Dolby sound, Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje could not be resurrected by 70 mm. However, the point is that, like 'Around the World' and ‘Sholay,’ the 35mm frames of Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje had to be cropped.

(The Amitabh Bachchan-starrer 'Mr. Natwarlal' was shot in normal 35mm, but by 1979, when it was released, the widescreen craze had become so pronounced that the film was reformatted and released in CinemaScope. Mughal e Azam is the other major film to be reformatted from normal 35mm to CinemaScope.)

Film historian Chamunda Binay Kumar Pandey has graphically shown how extra images (‘information’) along the four sides of the original 35mm version had to be lopped off to achieve the widescreen ratio of 70mm. Two 70mm images from Sholay, framed by Chamunda within the 35mm original, can be seen on this page. (From Chamunda’s article ‘Sholay - Special Edition DVD of Alternate Version.’[2])

After the success of Pakeezah there was enormous demand, at least among educated audiences, for CinemaScope. By 1972 most theatres even in B and C towns had installed widescreens meant for CinemaScope. In those days the men who controlled Hindi-Urdu cinema were slow to adapt to new technology. So, India had a situation in which there were widescreens everywhere but no Hindi-Urdu CinemaScope films to project on them.

In Delhi the managements of first Chanakya and then Kamal (both theatres are now defunct) decided to take things into their own hands. They purchased powerful projector-lenses and started blowing up normal (3:4) 35mm prints of films like Jawani Diwani and Bawarchi respectively (both 1972) onto the 1:2.35 screen--lopping off the top and bottom (but not the right or left), somewhat like the makers of 'Around the World,' ‘Sholay’ and 'Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje' have done officially.

The 70mm trend catches on

By the 1970s, the trend in Hyderabad was to build two-screen bi-plexes—with one ‘35mm theatre’ (with CinemaScope facilities) for Telugu and Hindi-Urdu films, and one ‘70mm theatre’ for English language films, both within the same building.

The unprecedented nationwide success of Sholay started the trend of releasing a few prints of many blockbusters in the major Indian languages in 70mm. Because the number of films to be blown up to 70mm had reached the critical level, it did not make sense to continue to send prints to the UK or USA for processing in 70mm. MIS Prasad Film Laboratories, Chennai and Ramnord Research Laboratory were the first to process 70mm (65mm) films within India, though the resultant colours were normally not as appealing as those processed in the West. Prasad set up a ‘70MM Recording Division’ (for stereophonic sound).

Karma (1986), was arguably the last major 70mm hit in Hindi-Urdu. Shoddy, processed-in-India 70mm films did nothing to enhance their appeal either. Soon B films were being made in 70mm, and the format had lost favour internationally.

By the 1990s the grain and resolution of CinemaScope films reached the level of the 70mm films of yore. Therefore, the 70mm trend gradually faded away from Hindi-Urdu films, though it lingered on for a few years more in India's less populous linguistic regions, which had also been late to take to the trend of making ‘70mm films.’

An Indian 70mm camera

In 1991 T. V. Somasundaram, a cinematographer, pioneered a light weight sixty five mm (i.e. 70mm) movie camera, much lighter than its international counterparts. It had a variable and constant motor in one, flexible eyepiece tube, and could be mounted on a Steadicam. He tested the camera with raw stock purchased in the UK and exposed through the Carl Zeiss lens of a Hasselblad still camera. The results were fairly good in terms of colour and sharpness, edge to edge. There was no formation of grains. [3] However, by then the 70mm era was almost over.

Some Indian films in 70mm

"Around the world"(Hindi-Urdu)1967 Above average; the no.11 earner of the year, but despite hit songs was not the superhit that its big budget demanded.

"Sholay"(Hindi-Urdu)1975 By some calculations the biggest grosser in Indian history.

"Padayottam" (Malayalam)1980

“The Burning Train” (1980) (Hindi-Urdu)Flop

Shaan (Hindi-Urdu)1980 Flop

"Badle Ki Aag" (Hindi-Urdu)1982 Above average. The no.15 grosser of the year.

"Razia Sultana" (Hindi-Urdu)Flop

"Mahaan" (Hindi-Urdu)1983. Made money because Mr Bachchan acted in it, but not a hit by his standards. No. 10 that year.

"Saagar"(Hindi-Urdu)Above average. No. 11 in the commercial rankings of 1985.

"Karma" (Hindi-Urdu)1986 The no.2 hit of the year

"Thandara Pappa Rayudu" (Telugu)

"Samraat" (Telugu)

"Dayavan" (Hindi-Urdu)1987 Above average. The no.7 grosser of the year.

"Saravegada Sardara" (Kannada)

"Maa Veeran" (Tamil)

"Simhasanam" (Telugu)

Ram Gopal Varma's "Raat" (Hindi-Urdu/ 1992)was a 'B film' The no.39 film of the year. Way below average success--sank and took 70mm down with itself. Was perhaps the last 70mm film in Hindi-Urdu.

‘Swapna Sagar’ (Odiya)(1983)

All commercial rankings given in this article are from ibosnetwork.com

Pakistan: theatres

South Asian countries other than India did not produce70mm films. Bambino cinema, Karachi, inaugurated by then president Ayub Khan in 1968, was home to the first 70mm projection screen in Pakistan. On September 21 2012, protesters denouncing an anti-Islam film set on fire the Bambino, Capri, Gulistan Talkies, Nigar, Nishaat and Prince cinemas, while in Peshawar, they stormed the Capital, Naz, Shabistan and Shama cinemas. The Karachi cinemas were destroyed; the ones in Peshawar damaged.

35mm (normal) vs. 35mm CinemaScope vs. 70mm

Oklahoma! (1955/ USA) was the world’s first feature film in 70mm; Povesti Plamennikh Let/ Chronicle of Flaming Years (1961/ USSR) the first made in the socialist bloc; and Flying Clipper – Traumreise unter weissen Segeln (1962/ West Germany) the first made in Western Europe.

70mm and 35mm indicate the width of the film—and not of the screen on which the image is projected. The ratio of height: width (i.e. the ‘aspect ratio’) of 70mm film is 1:2.20. The screen should be in at least the same ratio. 70mm films require special projectors, special cameras and a film that is twice as wide as 35mm.

‘Normal’ (non-anamorphic) 35mm films (e.g. Pather Panchali, Sangam, Kadalikka Neramillai, Pyaasa and the original Mughal-e-Azam) have an ‘aspect ratio’ of roughly 3:4 (actually, 1:1.37). That is also the ratio of the screens they need for projection.

CinemaScope, on the other hand, is the name of a process (and of a lens). CinemaScope movies are shot on standard 35mm film. However, the image that emerges from a ‘CinemaScope projector’ (i.e. a normal 35mm projector with an anamorphic lens) has an ‘aspect ratio’ of 1:2.35. The CinemaScope screen, thus, must have the same ratio, too.

In other words, CinemaScope uses not only normal 35mm film but the same projector, too. During the shooting, an anamorphic lens—i.e. a 'CinemaScope lens'—shoots a wide image but compresses it horizontally on 35mm film, the aspect ratio of which is almost half as wide.

A screen meant for CinemaScope films has to be wider than one for 70mm films--if the height is the same. Therefore, when a 70mm film is projected on a ‘CinemaScope screen,’ vertical strips of white space are left blank on the left and right of the 70mm image.

Now, the small 35mm film contains a slightly bigger image than the twice-as-wide 70mm. This is because 35mm normal has an aspect ration of 1:1.37 or almost 3:4. But when the image on the 35mm film is widened through an anamorphic lens onto a 1:2.35 'CinemaScope' screen, obviously the image will not be as sharp as an image projected from 70mm on the same screen (or on a 1:2.20 '70mm' screen, on which it will be sharper still). That is why filmmakers with big-budgets preferred 70mm.

However, with dramatic improvements in lenses, by the 1990s CinemaScope films started looking as crisp as the 70mm films of yore. Besides, they were cheaper to shoot, to make copies of and to project. Therefore, 70mm slowly faded away from India—and elsewhere. In the USA two 70mm feature films have been made since 1997 (Samsara (2011) and The Master (2012)); in Europe one 70mm feature after 1994 (As Wonderland Goes By (Australia/Bulgaria 2012)); and in Russia none after 1994. wikipedia (This list does not include films short partially in 70mm and short films.)

(The width of 70mm film is exactly that--70mm. However, the image is only 65mm wide. The remaining 5mm contain the sound--6 track stereophonic sound or better. By the early 1980s even Indian films in 35mm CinemaScope had stereophonic sound, and by the early 1990s DTS and Dolby sound. So, even that justification for 70mm disappeared.)

Cinerama theatres in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

Cinerama was a 3-strip, three-projector technology. Each 35 mm projector ran one third of the image, which was projected on a screen that had a 146° arc, and was much bigger than the 70mm widescreen. How the West Was Won (1962) is the most famous Cinerama feature ever, followed in popularity by an entertaining documentary ‘This is Cinerama’ (1952).

Like Imax after it, 3-Strip Cinerama concentrated on documentary films and only two features were ever made. The other feature, The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962)was a biopic.

In 1965 a trial screening of the Cinerama print of How the West Was Won in New Delhi was not successful, with the three projectors not synchronising.

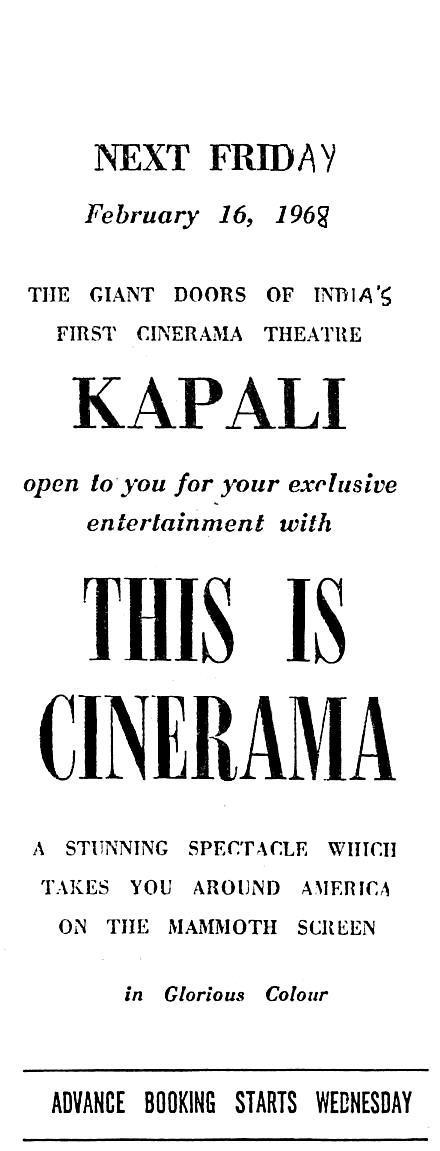

On 16 February 1968, Bangalore got India’s first Cinerama theatre, Kapali. It had a louvered 84ft by 32ft screen, and 1,500 seats, almost one and a half times as many as at Delhi’s biggest, Shiela. Kapali first screened This is Cinerama and then Seven Wonders of the World.

Karachi’s Capri opened five months later, on 26 July 1968, with a 35mm film projected on its 70ft by 30ft Perlux screen. An international register of Cinerama theatres notes that ‘no known Cinerama presentations’ were screened at Capri. [4]

The only other Cinerama theatre in South Asia was Colombo’s New Theatre, about which the same authority has no further details. Many countries around the world never constructed a Cinerama theatre, and many just one each.

The cumbersome three-projector Cinerama gave way to single-film 70 mm Cinerama. It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), which was filmed in Ultra Panavision 70, was the first of the lot, and a commercial success. A number of successful films were filmed in Ultra Panavision 70, but projected instead on normal widescreens made for 70 mm. Slowly this technology, too, disappeared.

3D

The first 3D film produced in India, My Dear Kuttichathan (1984), was made in Malayalam. Following its phenomenal commercial success it was dubbed into Hindi and released in 1985 as Chhota Chetan. Shiva ka Insaaf (1985) was the first 3D film made-for-Hindi. The 3D trend petered out after that, only to be revived, and brought right into the mainstream, by the success of the Hollywood blockbuster Avatar (2009).