Pt Jawaharlal Nehru

This page is under construction

Contents |

China

Nehru did not trust the Chinese

Diplomat G Parthasarathi’s notes claim that Indira Gandhi and Deng Xiaoping reached a pact that was ‘sabotaged’

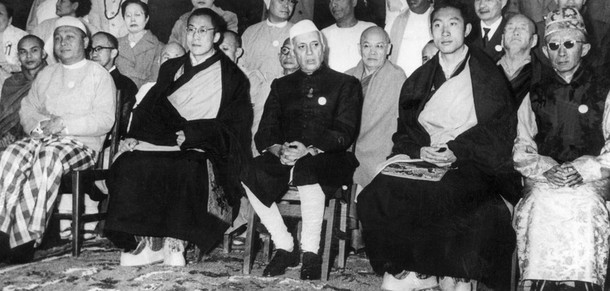

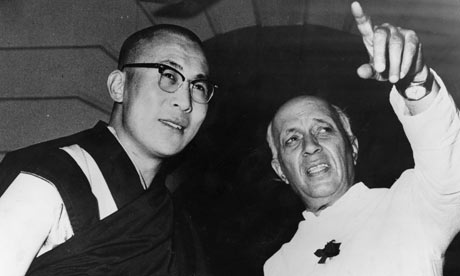

Contrary to the prevalent perception, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was neither soft on China nor trusting of the Chinese. In fact, long before the Sino-Indian war of 1962, Nehru dealt with China only through trusted aides who were sworn to secrecy and bound to communicating with him alone. Nehru was particular that his Defence Minister V K Krishna Menon should not get so much as a whiff of what was going on (vis-à-vis the Chinese), and explicitly said so to his aides.

This is revealed in a new book on G Parthasarathi, the multifaceted diplomat and policy advisor to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who had also served under Jawaharlal Nehru and Rajiv Gandhi. Nehru sent GP, as he was known, as India’s ambassador to China in 1958.

Securing border with China

Nehru was torn between loving Chinese civilisation & securing Indian border

Tansen Sen

Jawaharlal Nehru's first noteworthy encounter with the Chinese took place at the World Congress of Oppressed Peoples held in Brussels in 1927. The Chinese representatives, which included Sun Yat-sen's wife Soong Ching-ling, greatly impressed Nehru. Influenced by a new pan-Asianist discourse he started forming his views about a civilisational affinity between India and China.

He frequently voiced his sympathies for the Chinese fighting against invading Japanese forces and initiated a medical mission to China that included Dwarkanath Kotnis. He was a key patron of Cheena Bhavan in Shantiniketan and also saw great potential in developing trade and industrial relations; strongly advocating, for example, commerce through the newly built Burma Road.

The watershed moment in Nehru's relationship with China came at the Asian Relations Conference in Delhi in March-April 1947, where differences between India and China on Tibet became apparent when the organising committee invited Tibet as an independent country. China launched a strong protest with the interim Indian government. Chiang Kai-shek only agreed to send a delegation after Nehru assured the Chinese that the conference would deal primarily with cultural and economic matters, and that Tibet's status would not be raised.

Nehru's assurances were questioned, however, when the Chinese delegation found a map of Asia depicting Tibet as a separate country and the Tibetan flag displayed at the Conference. The Chinese threatened to withdraw and never trusted Nehru again.

In November-December 1949, the former Kuomintang ambassador in Delhi Lo Chia-lun sug gested to Chiang Kai-shek that the Indian PM might recognise the newly-established Communist regime in China in exchange for their acceptance of the 1914 Simla Agreement. However, the Communist regime was distrustful of Nehru, describing him as a “stooge“ and “running dog“ of British and American imperialists.

During the 1950s Nehru was torn between his love for Chinese civilisation, his empathy towards the Tibetan people, and the need to secure Indian territories. Further, Nehru did not heed Sardar Patel's warning in 1950 about the implications of future Chinese military expansion into Tibet.

Perhaps through the rhetoric of a bhai-bhai relationship, the Panchsheel Agreement of 1954 recognising Tibet as a region of China, and the handholding of Zhou Enlai at the 1955 Bandung Conference, Nehru hoped to convince China of India's stand on border areas. He may even have thought that the dual track of rhetoric and the so-called “forward policy“ were conducive. Indeed, he remained committed to a peaceful relationship, unwaveringly supporting the PRC's entry into the United Nations.

In this context, his decision to intern Chinese migrants in India when the relationship between the two countries deteriorated in 1959 cannot be comprehend ed. The punitive actions against the “Chinese Indians“ suggest an acknowledgement of agonising failure.In 1943, in jail, Nehru wrote, “What is there that draws China to India and India to China?

Something in our subconscious racial selves? Some forgotten memories of a thousand years ago? Or just common misfor tune?“ Right after jotting these lines, he added, “wishful thinking“. These two words must have echoed repeatedly as Nehru tried to come to terms with geopolitical realities ex posed by the 1962 war.

Canards about Nehru

Canards about Nehru

Edwina Mountbatten

‘Edwina, Nehru never alone to be lovers’

My Mother Found 'Companionship' In Pandit Nehru: Mountbatten's Daughter|July 30, 2017

Jawaharlal Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten loved and respected each other but their relationship was never physical as they were never alone, says the daughter of India's last vicereine.

Pamela Hicks nee Mountbatten was 17 when her father Lord Louis Mountbatten came to India as the last Viceroy. She saw a "profound relationship" developing between Nehru and her mother Edwina Ashley.

"She found in Panditji the companionship and equality of spirit and intellect that she craved," Pamela says. Pamela was keen to know more about the relationship.

But after reading Nehru's inner thoughts and feelings for her mother in his letters, Pamela "came to realise how deeply he and my mother loved and respected each other".

Pamela says she had been "curious as to whether or not their affair had been sexual in nature" but after having read the letters, she was utterly convinced it hadn't been.

"Quite apart from the fact that neither my mother nor Panditji had time to indulge in a physical affair, they were rarely alone. They were always surrounded by staff, police and other people," Pamela writes in "Daughter of Empire: Life as a Mountbatten".

The book, first published in the UK in 2012, has been brought out in India as a paperback by Hachette.

Lord Mountbatten's ADC Freddie Burnaby Atkins also told Pamela later that it would have been impossible for Nehru and Edwina to have been having an affair, such was the very public nature of their lives.

Pamela also writes that while leaving India, Edwina wanted to give Nehru her emerald ring.

"But she knew he would not accept it. Instead, she handed it to his daughter, Indira, telling her that if he were ever to find himself in financial difficulties - he was well known for giving away all his money - she should sell it for him," the book says.

At a farewell party for the Mountbattens, Nehru said while addressing Edwina directly, "Wherever you have gone, you have brought solace, you have brought hope and encouragement.

Is it surprising, therefore, that the people of India should love you and look up to you as one of themselves and should grieve that you are going?"

Religion

Scientific, Rational Humanism

Ashok Vohra, August 31, 2019: The Times of India

Many view the agnosticism / atheism of Nehru as a serious shortcoming of his persona. They feel that “the greatest lack in him was his inability to believe in God.” Nehru remained a hardcore rationalist throughout his life. Nehru found the concept of God itself unintelligible and incomprehensible. In The Discovery of India, he said, “I find myself incapable of thinking of a deity or of any unknown supreme power in anthropomorphic terms, and the fact that many people think so is a source of surprise to me. Any idea of a personal god seems very odd to me.”

However, he always wondered about the sway that the concept of God had on the inner craving of humankind, which “brought peace and comfort to innumerable tortured souls”.

Countering the argument of those who upheld the necessity of God, Nehru maintained that, “even if God exists, it may be desirable not to look up to Him or to rely upon Him.” He argued that “too much dependence on supernatural factors may lead, and has often led, to a loss of self-reliance in man.” It would, according to him, ultimately result in “blunting of his (man’s) capacity and creative ability”.

Though Nehru rejected the traditional notion of God, he argued, that, “some reliance on moral, spiritual and idealistic conceptions is necessary,” for without such a belief “we have no anchorage, no objectives or purpose in life.”

Nehru had immense faith in the human spirit that overcomes nature and brings about great human convulsions. He advocated ‘scientific humanism’ – the synthesis of humanism and scientific spirit. Scientific humanism advocated by Nehru “is practical and pragmatic, ethical and social, altruistic and humanitarian. It is governed by a practical idealism for social betterment”.

Scientific humanism treats humanity as its god, and social service as its religion. It recognises the fact that “every culture has certain values attached to it, limited and conditioned by that culture.” It also recognises that human nature is such that “every generation and every people suffer from the illusion that their way of looking at things is the only right way” to knowing and realising the truth to which they accord permanent validity.

Scientific humanism upholds a radically opposite view, namely, that “the values of our present day culture may not be permanent and final; nevertheless, they have an essential importance for us, for they represent the thought and spirit of the age we live in.”

He had almost the ‘devotion of a faith’ in human virtues and his unlimited capacity to struggle and emerge victorious in any kind of adverse situation. The virtues of man which impressed Nehru most, were man’s indomitable and undaunted spirit which seeks to mount higher and higher, his “gallant fight against the elements, his courage that overcomes nature itself, his limitless endurance, his high endeavour and loyalty to comrades and forgetfulness of self, and his good humour in the face of every conceivable misfortune”.

Like Sartre, Nehru, too, upholds the view that man continually accepts the challenges faced by him in achieving the targets and goals chosen by him. “Life,” according to him “is a principle of growth, not of standing still, a continuous becoming, which does not permit static conditions.” For man, life is a long adventure and an opportunity to test his will and worth. He does not rest till goals are reached. From every disappointment and defeat, the spirit of man “emerges with new strength and wider vision”.