Dilip Kumar: his films, their box office performance, awards, career

2017: This page is being expanded

If you wish to contribute photographs and/ or biographical details about Dilip Kumar (or any other subject), please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name. * |

The sources of this article include

i) The real superstars of Bollywood - Dilip Kumar Jagran Junction 30 Aug, 2011 'Masti Maalgadi'/ Jagran Junction.

ii) Nasir’s Eclectic Blog Tuesday, December 1, 2009

iii) Nasir’s Eclectic Blog Tuesday, December 1, 2009

iv) Excerpted from `Dilip Kumar: The Substance and the Shadow' with permissions [obtained by The Times of India] from Hay House India and Penguin Books India The Times of India Jun 01 2014

Dilip Kumar’s place in cinema history

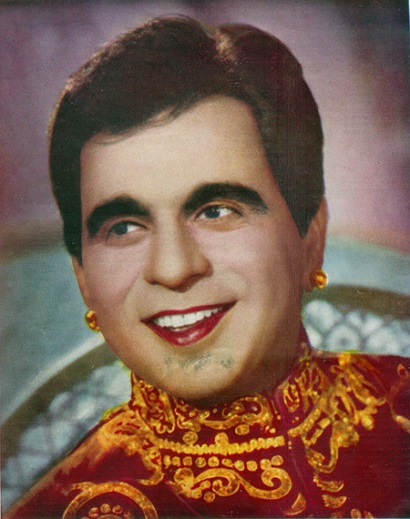

From roughly 1947 to 1964 Dilip Kumar was the no.1 star of Hindi-Urdu films: in terms of the hits that he delivered, in terms of the fee that he commanded and in terms of the awards and critical acclaim that he won.

Profile

Dilip Kumar was born on December 11, 1922 in the city of Peshawar in present-day Pakistan. His childhood name was Mohammad Yousuf Khan (Muhammad Yusuf Khan). His father, Lala Ghulam Sarwar used to sell fruit to feed his family.

Early life

His family migrated to Bombay during the Partition of India. He passed his early life in difficult conditions. The losses in the trade of his father made Dilip work in a canteen in Pune. That was where Devika Rani first sighted him, and it was from there that she made an actor of Dilip Kumar. Dilip Kumar was the new name that he assumed.

Bhojpuri As a youngster, he spent many years in the hill town of Deolali in Maharashtra. Once, squatting in the kitchen of their gardener he heard a dialect of Hindi which, he says, fascinated him. This was Bhojpuri, though he didn't know that at the time. "It sounded fascinating and there was a vivid expressiveness about it while conveying raw emotions," he recalls. His Gunga Jumna is noted for its authentic use of Bhojpuri and the actor says the film came from his long ambition to work the magic of the dialect into a story on screen.

In 1947, when he was twenty-five years old, Dilip Kumar was the star of what, according to most sources, was the no.1 hit of the year. He tasted superstardom as early as that. His position at the top was cemented the next year. He was rapidly accepted as the country's number one actor.

Filmography (with the box office rank of each film)

Today Indpaedia is the only place where you will find lists of the biggest Hindi-Urdu film hits of each year, from Hindi-Urdu films: 1931 to the present. Films have been ranked according to their box office success in the year of their release. For the 20th century we obtained our information from the archives of BoxOfficeIndia.com and IbosNetwork.com. Wherever there was a difference of opinion between these two authorities we have mentioned the higher rank first.

Filmography: As an actor...

1944-49

1944 Dilip Kumar’s career got off to a good start with his debut film doing fairly well at the box office.

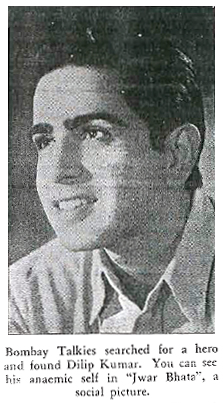

1944 Jwar Bhata No. 6. Not at all bad for a debut film. Quite good, in fact.

1945 An average year for him.

1945 Pratima Not in the Top 7.

1946

Milan (Nauka dubi) was Dilip Kumar's first success (no.3 according to one authority) and the film had an impact on audiences. Dilip Kumar had arrived with his very third film. Some very respected authorities claim that the film was released in 1947. Harmandir Singh 'Hamraaz,' who is the most meticulous chronicler of Filmistan's songs, gets his facts from the most primary of sources: first edition record labels. He has filed Milan's songs under 1946, therefore, Indpaedia believes that there is no room for further debate.

1947 Dilip Kumar had a very good year.

1947 Jugnu No. 1 (BoxOfficeIndia.com) or no. 5 (IbosNetwork.com). Either way, it was Dilip Kumar’s first major hit.

1948 probably was the year in which Dilip Kumar drew close to superstardom. He starred in the no.1 hit, which stirred the nation, and had another two films in the Top 6.

1948 Shaheed was no.1 on some charts (and Raj Kapoor’s Aag on others)

1948 Mela No. 4

1948 Nadiya Ke Paar No. 6

1948 Anokha Pyar

1948 Ghar Ki Izzat

1949 was another year in which Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor shared the no.1 slot: this time in the same film.

1949 Andaz No.1

1949 Shabnam No.5

1950- 54

1950 Three films in the Top 9.

1950 Babul No. 2 or 4.

1950 Jogan No. 4 or 5.

1950 Arzoo No.9

1951

1951 Deedar No. 4

1951 Tarana No.7

1951 Hulchul

1952

1952 Aan No.1 There is a debate about the year in which Aan was released. 1952 is the most likely year.

1952 Daag No.4 <> Filmfare’s ‘Main Award’ of 1954 Best Actor Daag (for the year 1952) {If Dilip Kumar did not win major awards before 1952 it was because Filmfare awards were instituted in only in 1954 and there were no major awards before that.)

1952 Sangdil no.5

1953

1953 Foot Path No.5

1953 Shikast No.7

1954

1954 Amar No.9

1955-59

1955

1955 Azaad No.2 <> 1956 Filmfare Award Best Actor Azaad (1955)

1955 Devdas No.4, but one of the most influential Hindi-Urdu films of all times. Till at least the 1980s every time Devdas was re-released it would do reasonably well at the box office, a distinction that only one other film, by a coincidence also starring Dilip Kumar, can claim: Mughal e Azam. <> 1957 Filmfare Award Best Actor Devdas (1955)

1955 Insaniyat No.6

1955 Uran Khatola No.10

1956 No Dilip Kumar release

1957

He was called the ‘great mumbler’ for the way in which he mumbled some of his dialogues, for instance ‘Maa’ in Mughal-e-Azam.

However, look at his poker face in this frame. His beaming screen mother wants him to get married to Rajni, whom he loves and wants to marry. However, like a good Indian/ South Asian son of 1957 he is not supposed to admit to feelings of romantic love in front of his parents. So, while he is bursting with happiness inside, Shankar (Dilip Kumar) pretends to agree to marry Rajni (played by Vyjayanthimala) only to please his mother. He even feigns that he is not sure who this Rajni is.

This classic bit of Method Acting can be viewed at roughly 57:30 in the colourised version of the film Naya Daur

Above: Leela Chitnis (who plays his screen mother) with Dilip Kumar in Naya Daur (1957)

1957 Naya Daur No.2 (behind only the unbeatable Mother India) <> 1958 Filmfare Award Best Actor Naya Daur (1957)

1957 Musafir No.10

1958

1958 Madhumati No.1 <> 1959 Nominated Filmfare Award Best Actor Madhumati (1958)

1958 Yahudi No.3

1959

1959 Paigham No.2

1960-69

1960

1960 Mughal-e-Azam No.1: adjusted for population and inflation, by some calculations, the biggest hit in the history of Hindi-Urdu cinema

1960 Kohinoor No.3 <> 1961 Filmfare Award Best Actor Kohinoor (1960)

1961

1961 Gunga Jumna No.1 <> 1962 Nominated Filmfare Award Best Actor Gunga Jumna (1961)

1962 and 1963 No Dilip Kumar releases. With hindsight, his bad period had begun.

1964

1964 Leader No. 11 or 15. The first major flop of Dilip Kumar’s career <> 1965 Filmfare Award Best Actor Leader (1964)

1965 No Dilip Kumar release

1966

1966 Dil Diya Dard Liya No. 13. Dilip Kumar’s second major flop <> 1967 Nominated Filmfare Award Best Actor Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966)

1967 Dilip Kumar had not had a hit in six years. 1967 gave him a brief respite.

1967 Ram aur Shyam No.2 or 4 <> 1968 Filmfare Award Best Actor Ram Aur Shyam (1967)

1968

1968 Aadmi No.7 At the time it was seen as a flop. However, ultimately, the film did average business.

1968 Sunghursh No. 12 or 18. A highly regarded film that did badly at the box office.

1968 Sadhu aur Shaitaan No.13 or 21. Cameo.

1970-74

1969-72 There were no Dilip Kumar releases.

1971: There was no Dilip Kumar release.

1972 Dilip Kumar fans got to see their idol in a lead role again—two in fact.

1972 Dastaan No.20. Despite Dilip Kumar’s double role this remake of Afsana did not do well.

1972 Anokha Milan (Guest appearance) Not in the Top 22.

1972 Koshish Cameo. Not in the Top 22.

1973 Gopi No.12. Not a hit. However, given Dilip Kumar’s lately lowered box office standing, it had decent earnings.

1974 Dilip Kumar was back in the romantic lead (opposite his real life wife, the beautiful Saira Banu, 22 years his junior) in Sagina.

1974 Sagina No.18. It was a sincere film about the working class but the Hindi-Urdu version did not do well at the box office.

1974 Naya Din Nai Raat Voice only. Not in the Top 23.

1974 Phir Kab Milogi Cameo. Not in the Top 23.

1975-84

1975 No Dilip Kumar film was released.

1976 At age 54 Dilip Kumar played his last role in the romantic lead.

1976 Bairaag No.16. It was a triple role and his leading ladies included not only Saira Banu but also the twenty-something Leena Chandravarkar. The film did average business.

1977-1980 No Dilip Kumar film was released.

1981 Manoj Kumar, north India’s best-known actor director of patriotic films had never made a secret of his adulation of his childhood hero, the patriotic Dilip Kumar of Shaheed. It was he who gave the 59-year-old Dilip Kumar his second coming and top billing in the 70mm period opus Kranti. It was a mature role but was one of the causes of the film’s success.

1981 Kranti No. 1 or 2 film of the year (rivalled only by Naseeb).

1982 There was a huge demand among Hindi-Urdu audiences for a histrionic clash between the reigning no.1 Amitabh Bachchan and the greatest living actor of commercial Hindi-Urdu cinema. Shakti, in which they played son and father, did well but was not the superhit that it was expected to be, because the script was not the world’s best.

Vidhaata, on the other hand, gave Dilip Kumar the kind of role his fans wanted to see him in. he was the head of a middle-order starcast, had the title role and drove the film to the top of the charts.

1982 Vidhaata No.1 or no.4.

1982 Shakti No.3 or 8. <> 1983 Filmfare Award Best Actor Shakti (1982)

1983 Though Dilip Kumar played a mature role in Mazdoor, he was the focus of the film, which did not do well.

1983 Mazdoor No. 23.

1984 saw Dilip Kumar in two author-backed roles, both written by Javed Akhtar. Mashaal was the strongest script that Javed had written after his split with Salim. It has acquired a cult status and its Ai bhai scene is affectionately parodied even in the second decade of the 21st century. Once again Dilip Kumar played not someone’s father but an idealist who is driven to crime.

While Duniya did below average business, Mashaal was a washout at the box office.

1984 Duniya No.17.

1984 Mashaal No.30

1985-98

1985 No Dilip Kumar release.

1986 Dilip Kumar was back at the top with Karma, a 70mm opus with a tailor-made role as a brave and incorruptible police officer. Dharm Adhikari had him in the title role of an honest justice of the law. However, the film was a non-starter at the box office.

1986 Karma No. 1 or 2 (tying with the formidable Aakhree Raasta)

1986 Dharm Adhikari Not in the Top 42.

1987-88 No Dilip Kumar film was released.

1989

1989 Kanoon Apna Apna No.21. Below average.

1990

1990 Izzatdaar No.18. Below average.

1990 Aag Ka Dariya Not in the Top 50. A non-starter.

1991 Once again Dilip Kumar was back in the top rungs in an author-backed role in a film in which the young romantic couple was a mere decoration and the focus was on Dilip Kumar and veteran Raaj Kumar. Saudagar was Dilip Kumar’s last hit.

1991 Saudagar No.3

1992-97 Despite Saudagar’s success Dilip Kumar did not star in another film for the next six years.

1998 saw the swansong of one of the greatest actors and superstars of Hindi-Urdu cinema

1998 Qila was a washout. It was not in the Top 50.

Filmography: As a writer

1961 Gunga Jumna

1964 Leader

As a producer

1961 Gunga Jumna <> 1962 Filmfare award for Best Film Gunga Jumna (1961)

DK's career in brief

DK’s body of work

Dilip Kumar movies have gone on to become great classics of Indian Cinema. In his early films, Dilip Kumar mirrored the frustration of youth in upholding life’s values and ideals. For him, it was not the case of “Everything is fair in love and war.” For him, being noble was more important than winning love by aggression or deception or crossing the limits of civility. His romantic losses and longings endeared him greatly to his generation and the next, which did not want any shades of grey in the roles he played as in Amar (1954) and Qila (1998). His swashbuckling roles in Aan and Azaad sent the message of fighting evil with will and determination, taking pains in strides. When he came on the screen hearts missed their beat and the entire audience-filled hall lighted up at the very sight of him.

There is something enthralling about him, his mutterings, his pauses, meaningful shifting of eyes, furrowed forehead, gesturing hands, short chuckles, smiling lips, inspiring speeches, tragic monologues, Heathcliffian determination, rustic innocence, romantic disposition, and the face that expresses tragedy of the mind and happiness of the heart.

1942-47

Dilip Kumar began his film career with the film Jwâr Bhâtâ ("Tides"); however, the film was not successful. His first hit was Jugnu ("Fireflies"). The film was released in 1947 and placed Dilip Kumar in the category of Filmistan’s successful film-stars.

In 1942, Yusuf Khan (Dilip Kumar) was in jail overnight. He refused to have his breakfast of eggs, toast and tea, which was offered to him the next morning because that day Mahatma Gandhi was on fast. The nation was busy with the Quit India Movement of 1942, for driving out the British Raj. During the next two years life was to take unexpected turn for Yusuf Khan when Devika Rani, the lady boss of Bombay Talkies, offered him a contract to act in her films.

After initial hiccups Yusuf Khan accepted the offer and thus landed a role in Jwar Bhata (1944) under the name that the First Lady of the Indian Screen selected for him – Dilip Kumar - the name that was to cast a spell on generations of filmgoers for the next six decades. Thus he made his debut as an actor opposite Mridula and Shamim under the direction of Amiya Chakarborty. Dilip Kumar did two more films, Pratima (1945) and Milan (1946) after Jwar Bhata.

1947-53

Jugnu (1947), Ghar Ki Izzat, Mela, Shaheed, Anokha Pyaar and Nadiya Ke Paar (all 1948); Shabnam and Andaz (1949); Jogan, Babul and Arzoo (all 1950); Hulchal, Tarana and Deedar in 1951; Aan, Sangdil, and Daag (1952).

In 1949, Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor, the other rising star of the era, worked together with for the first time in the film Andâz . The film was a hit. Serious roles in films such as Deedâr (1951) and Devdas (1955) earned him the title King of Tragedy.

Daag which was inspired by the 1950 Marathi movie, Mee Daaru Sodli, won for Dilip Kumar his first Filmfare Award for his stellar performance of an alcoholic who having set out to purchase medicines for his dying mother, instead succumbs to his temptation and buys liquor for himself, and who finally manages to give up his drinking habits for good. In 1953, Dilip Kumar featured in Shikast and his favourite Foot-Path “where stark reality was mingled with thought-provoking romanticism.”

1954-59

Around 1954, Bimal Roy was busy shooting with Dilip Kumar his prestigious Devdas which was based on the Bengali novel of Sharatchandra Chattopadhyay.

In 1954, Mehboob Khan released his Amar, starring Dilip Kumar, Madhubala and Nimmi. From 1955 till 1959 Dilip Kumar starred in such films as Devdas and Udan Khatola, (1955); Insaniyat, and Azaad (1956); Naya Daur and Musafir (1957), Madhumati and Yahudi (both Bimal Roy’s – 1958). During these years, Dilip Kumar won the Filmfare Best Actor Awards for his roles in Devdas, Azaad and Naya Daur! He also got the nomination for the said Award in Madhumati. Dilip Kumar did Paigham (1959) along with Raj Kumar, Vyjayantimala and B. Saroja Devi. He was cited for the Filmfare Best Actor Award nomination [not confirmed].

1960-69

Dilip Kumar, in 1960 he had two releases: Kohinoor and Mughal-e-Azam. He again won the Filmfare Best Actor Award for Kohinoor.

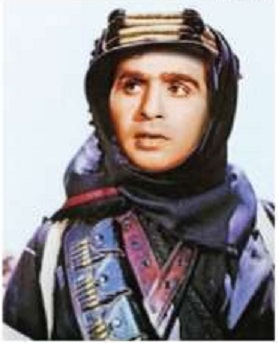

In the all-time blockbuster Mughal-e-Azam (1960), he played the role of the Mughal prince Jahangir.

In 1961 he wrote, produced and acted in Ganga Jamuna which was a trend-setting movie in many respect. This mile-stone of a movie elicited a very powerful performance from Dilip Kumar.

Sophia Loren, the two times Oscar Winner, was influenced profoundly by his acting. Astonishingly, Dilip Kumar did not win the Filmfare Award. He was of course nominated under that category.

After a three-year hiatus, Dilip Kumar accepted the role of Leader (1964) for Sashadhar Mukherjee. He also wrote the film-story which is as relevant today as it was then. His comedy role fetched him another Filmfare Award in the Best Actor Category.

His second coming

Dilip Kumar played a double role in Ram aur Shyam. The film was a superhit after a lean period that saw Leader and Dil diya dard liya flop.

His movies in the second half of the Sixties are: Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966); Ram Aur Shyam (1967), Sungharsh, and Aadmi (both 1968).

He was nominated in the Best Actor Category in all the four films. In Ram Aur Shyam Dilip Kumar played the full-fledged double role for the first time and his impact in the movie was such that it won many acclaims, including the prestigious Filmfare Award for his diverse, sensitive and powerful performance. His adverse critics, who thought he was finished, were deservingly dealt a serious blow.

However, his next few films, notably the critically acclaimed Sunghursh and Dastân did not do well either.

The 1970s

In Nineteen Seventies we have four Dilip Kumar movies: Gopi (1970), Dastaan (1972), Sagina (1974) and Bairaag (1976). All three movies, excluding Dastaan, had his better-half, Saira Banu, as his heroine, while B.R. Chopra’s Dastaan which was a remake of Afsaana (1951) had Sharmila Tagore and Bindu. In the Seventies he also had a guest appearance Phir Kab Milogi (1974) – a Mala Sinha-Biswajeet starrer.

Sagina Mahato (1970) was his diamond-jubilee hit Bengali film which was directed by Tapan Sinha. It created box-office records in Bengal.

Portrayed as a brooding tragic hero, Dilip Kumar was actually quite athletic. In Sagina Mahato, one of his later critically acclaimed films, there is a sequence where the character feeling claustrophobic in an office takes off on a sprint alongside a speeding train. "When I suggested the scene to Tapan da, he liked the idea very much. He looked at me and asked me in his quiet manner if I could wait for a double to be arranged for the run. He stared at me in disbelief when I told him I would do the sprint myself." The shot was done in one take.

Anokha Milan (1972) had Dharmendra along with him.

In Bairaag, Dilip Kumar had triple roles, that of a father and his two sons. Bairaag additionally had the beautiful Leena Chandavarkar also as his heroine. This was the last movie of Dilip Kumar where he was the romantic hero. Thus from 1944 to 1976 he played the roles of a film hero for 32 long years.

The 1980s and ’90s

His third coming

When Dilip Kumar came back to the silver screen after five years in Kranti (1980) it was his second innings but a successful one too. Stories were written for him, contemplating him in a central role. Thus we have Shakti and Vidhata (1982), Mazdoor (1983), Duniya and Mashaal (both 1984), Karma and Dharam Adhikari (Both 1986), and Kanoon Apna Apna (1989), Izzatdaar (1990)) and Saudagar (1991) and Qila (1998). In Shakti Dilip Kumar had Amitabh Bachchan, the super-star of the time, pitted against him. However Dilip Kumar came out with such a brilliant performance that it won him yet another Filmfare Award in the Best Actor category. He was also nominated for the said Award in Mashal and Saudagar.

Ai Bhai! Dilip Kumar's performance in Mashal was again a trend-setter and his AY BHAI....scene has been emulated in many Bollywood movies. In Yash Chopra's Mashaal (1984), there is a heart-wrenching scene in which Dilip Kumar's character is shown standing on a road desperately looking for some help to take his very ill wife (Waheeda Rehman) to a hospital. But she dies in his arms, no vehicle willing to stop on the quiet night street. Dilip Kumar says the scene was a straight replay of his father's panic when his mother had a near fatal asthma attack.

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s he worked in relatively few films. However, such was the respect and fan following that he continued to enjoy that most of the films that he acted in in his 60s were major hits: Krânti (1981), Vidhâtâ (1982), Karmâ (1986).

Duniyâ (The world; 1984), Izzatdâr (The respectable one) (1990) and Saudâgar (Merchant) (1991) were big-budget films, if not as successful. His last film was Qilâ ("Castle"/ 1998).

2014: His last film to be released: Aag ka dariya

Dilip Kumar-starrer 1990 film set to hit theatres soon

ANI | Dec 25, 2013

'Aag Ka Dariya,' made in 1990, also starred actress Rekha. In thew film he plays a father in search of his missing daughter.

The director of the film, VS Rajender Babu, told BBC that the film did not get released initially because of a financial dispute and the original print of the film was badly damaged in the intervening years.

But in 2013 Babu found a "perfect print" of the film with a distributor in Singapore.

The film was to have finally been released in 2014. However, there is no reason to believe that it was ever released. It does not figure in Indpaedia’s list of the 150 most successful Hindi-Urdu films: 2014

Other unreleased films

Films starring Dilip Kumar that never got exhibited include: Chanakya, Kalinga, Raasta and Shikasta.

Iconic roles that Kumar refused

UpperStall writes:

Dilip Kumar refused Guru Dutt's Pyaasa (1957) feeling that the character of the poet Vijay in the film was just an extension of his role in Devdas. He also turned down 20th Century Fox's offer of The Rains Came and David Lean's offer of the role which ultimately went to Omar Sharif in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and which made a major Hollywood star out of Omar Sharif. To quote Dilip Kumar,

"In your own bazaar you enjoy a certain status. What's the point of venturing out into fields unknown where you have no say? No contact with the subject matter."

Dilip of Arabia?

Anvar Alikhan, The Times of India

How Omar Sharif owed his Hollywood career to Dilip Kumar

Omar Sharif burned his way into Hol lywood with Lawrence of Arabia. But what most people don't know is that the actor who was originally supposed to play Omar Sharif 's role in the film was Dilip Kumar.

Director David Lean was an Indophile thanks, partly, to the fact that his fourth wife was Leela Welingkar, a legendary Hyderabadi beauty. Lean had recently made The Bridge on the River Kwai, which had won seven Oscars, and he was now looking to make his next great blockbuster.

The question was who to cast as Sherif Ali, a character based on various tribal chieftains who had fought alongside Lawrence. Lean did not want to use a European star; he wanted a more authentic actor. That's when he got in touch with Dilip Kumar, whose work he knew because of his personal experience of India.

A meeting was arranged with Dilip Kumar, where the charming and persuasive Lean pitched the role to him. But Dilip Kumar turned him down, and the role went to Omar Sharif who had originally been cast to play Tafas, Lawrence's desert guide who, ironically, is shot dead by Sherif Ali in his iconic introductory sequence. Thus, what was intended as Omar Sharif 's end in the film, turned out, instead, to be the beginning of a famous Hollywood career.

But the big mystery, of course, is: why did Dilip Kumar turn down a part that any actor would kill for? It seems an inexplicable career decision, especially given the fact that David Lean was at his prime as a director, having won seven Oscars with his last film.

Strangely, Dilip Kumar's autobiography, The Shadow and the Substance, doesn't shed much light on the matter, so one can only speculate. Was it was because he was then busy with his ambitious Ganga Jamuna project? Or be cause he believed his loyalty was to his Indian audiences? Or simply because he found David Lean too domineering a personality and was worried that the chemistry wouldn't work? All that Dilip Kumar has said on the subject is that he thought Omar Sharif had played the role far better than he himself could have.

Whatever the reason, it may well rank as one of the worst career moves in cinema history.Dilip Kumar lost the opportunity to take his talent onto a whole new, international level, right at the prime of his career. A big loss, especially for an actor noted for his ability to take risks, to learn, and evolve with every new role.

One cannot help wonder: What if Dilip Kumar had, indeed, played the part? He was, unquestionably, a better actor than Omar Sharif (although, he might not have quite had Sharif 's homme fatale quality). He would have done a great job of Sherif Ali's role, quite likely even better than Omar Sharif did. He might have thus become one of Lean's pool of chosen talent, like Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins and Omar Sharif himself, whom the great director called upon to act in his subsequent productions.And then who knows what might have happened? Maybe, for one thing, Lean might have decided to make his critically acclaimed A Passage to India a couple of decades earlier, with Dilip Kumar playing a brilliant Dr Aziz.

But, that apart, Lawrence of Arabia would have opened other Hollywood doors for Dilip Kumar.And those experiences would have, in turn, helped enrich his future Hindi movie roles. He would have thus surely avoided the bad patch he went through in the 1970s, starting with Gopi and Sagina Mahato, which wiped out ten of the best years of his life.But one thing is for sure: Dilip Kumar would not, unlike Omar Sharif, have left Indian cinema and moved to Hollywood; he was too rooted, and modest, a person for that.

While Dilip Kumar did not act in Lawrence of Arabia, there was another Indian actor who did. And that was I S Johar, who played the minor role of Gasim, a Bedouin tribesman who Lawrence finally executes. The role got I S Johar his hour of glory back home in India, and [for] many Indians his two minutes on screen [were an added attraction of the film].

Quality, not quantity

In spite of being the highest paid and most successful star of the 1950s and early ’60s, Dilip Kumar acted in just 54 films. This indicated that he wanted to give only high quality performances.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Filmistan was ruled by a trinity of matinee idols: Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor (the most successful director of his time, though his acting was questionable) and Dev Anand.

Dilip Kumar’s autobiography: excerpts

Excerpted from Dilip Kumar | The Substance and the Shadow, an autobiography |As narrated to Udayatara Nayar |©2014 Dilip Kumar | Hay House Publishers

Childhood in Peshawar

[On the day of the] grand arrival of the fourth child of Mohammad Sarwar Khan and Ayesha Bibi [a] blizzard was raging outside and, what was worse, the Goldsmiths’ Lane was in flames, blocking normal transport. 11 December 1922. I suspect the date is mentioned somewhere in some chronicle of Peshawar’s history not because I was born on that dramatic day but because fire had gutted the gold- smiths’ workshops.

One ordinary day, when I was playing in the front room of our house, a fakir came to the door seeking food and some money.He fixed his stare on my face and told Dadi: ‘This child is made for great fame and unparalleled achievements. Take good care of the boy, protect him from the world’s evil eye, he will be handsome even in old age if you protect him and keep him untouched by the evil eye. Disfigure him with black soot if you must because if you don’t you may lose him prematurely. The Noor [light] of Allah will light up his face always.’

Dadi took it upon herself to protect me from the evil eye of the world. She had my head shaven and every day, when I started for school, she made a streak on my forehead with soot to make me look ugly. Amma tried hard to convince her not to make her child so ugly that other children would poke fun and give him a complex.

Aghaji [as Dilip Kumar called his father] tried to reason with his stubborn mother about the consequences of what she was doing to me. But Dadi wouldn’t budge. Her love and protectiveness towards me were too overwhelming for her to accept their pleadings.

Needless to say, I was a spectacle when I arrived in the school every morning. The murmurs and sniggers that greeted me on the first day amplified in my subconscious and made me find reasons not to go to school the next day. I gave vent to my unhappiness and narrated the derision I faced from my classmates and older boys of the school who were always ready to seize occasions to have fun at the expense of any junior who was easy prey to their pranks and jokes. It was the pain I endured as the alienated child in school that surfaced from my subconscious when I was playing the early tragic roles in my career and I had to express the deep mental agony of those characters.

Yet another pastime I indulged in solitude was imitating the ladies and men who came visiting my parents. Amma caught me at it one day and chided me gently, saying it was not good to make fun of elders. I was mimicking Khala [aunt] Mariam when she came in unexpectedly and saw what I was up to. I did not tell Amma that I was not making fun of Khala Mariam but I was trying to be Khala Mariam for a few moments because she was such an intriguing character.

Aghaji [DK's father] had many Hindu friends and one of them was Basheshwarnathji, who held an important job in the civil services. His elder son came to our house with him a few times and he stunned the ladies with his handsome appearance. That was Raj Kapoor’s father Prithviraj Kapoor. Basheshwarnathji was very friendly with Aghaji and I often heard them discuss an impending war (the Second World War) and what was in store for the inhabitants of Peshawar.I listened to their talk intently but I could not fathom what they were talking about. They were talking about a city called Bombay where business opportunities were many. Then one day I heard Aghaji tell Dada that he was going to Bombay to explore such opportunities and he intended to go alone first. The war was inevitable and it was bound to impact the fruit business as transportation of marketable produce from the orchards in Peshawar to markets elsewhere would become difficult. Before I knew it he was off to Bombay one morning.

The mid-1930s: The family shifts to Bombay

Though Dadi didn’t quite agree with her son’s move to shift the family to Bombay, for once Dada stood firm on his decision to give his daughter-in-law the right to live with her husband.

I think it was some time in the mid-1930s. The apartment rented out by Aghaji was in a four-storeyed structure called Abdullah Building on Nagdevi Street, near the bustling Crawford Market, where he had set up his fruit business on a wholesale basis at first.Aghaji seemed satisfied with his fruit business, which was prospering. He didn’t have to go to the fruit stall at Crawford Market every day as he had employed men to receive the consignments and deliver them at the market besides managing the daily sales.

In Bombay I was enrolled at the Anjuman Islam High School and there was no more shaving of my pate. I now wore my skull cap over a thick growth of black hair, which elicited compliments from all the ladies who visited Amma.

Deolali

As [DK’s brother] Ayub Sahab grew up, he developed a respiratory disorder, which necessitated our moving to Deolali (a hill station in Maharashtra, located about 180 km from Bombay). The fresh air in Deolali and the availability of medical care there made it the ideal location for his treatment and recovery.

Being an army station, Deolali had good educational institutions, and one of them was Barnes School where I was admitted.Deolali is of significance in my life in more than one respect. First, it was at Deolali that I learned the English language and became quite proficient in it. Secondly, it was during our stay in Deolali that I began to take keen interest in soccer.

There was an English poem that I learned in school, which I recited before Aghaji one day and he was so happy that he made me recite it before all his distinguished English-speaking friends. Each time I completed the recitation there would be encores. There would be cries of ‘shabash [well done] Yousuf’. Each time I had to start all over again. The encores came again and I would straighten myself, take a deep breath and begin reciting the same poem once again.

I think Destiny had already begun to chart out the life I had to lead.I think I was stimulated to perform by the applause and encores I received. It was as if I could see a door, a wall and a ceiling when I recited. I had my first brush with the make-believe world into which I was to make my fateful entry years later.

At Deolali, Ayub Sahab had no option but to spend his waking hours reading whatever Urdu literature he could lay his hands on. He always liked to read the latest novels and he devoured newspaper articles and short stories with great delight. To make him happy, as I grew up and progressed in my study of English, I read the short stories (in translation) of the nineteenth-century French writer, Guy de Maupassant, and narrated them to him. That was my first introduction to published literature from abroad and I was fascinated by the plot structure and storytelling ability of the author. In a latent sort of way, I was developing a keen narrative skill by reading the works of English and other European authors that I found in the library of Barnes School.

The climate was perfect and we had flowers and fruits in the trees in our garden, which was tended to by a jovial maali and his wife who spoke a UP (then known as United Provinces and later called Uttar Pradesh) dialect, which fascinated me. Many years later, when I began to work on the dialogues of the film Gunga Jumna (released in 1961), it was this dialect that came to my mind and ears repeatedly.

Deolali, as a picturesque place, figured prominently in my imagination when we got down to de- tailing locations in the screenplay of Gunga Jumna. The hills, the plains and the thick groves made up of all varieties of woodland trees lining the banks of the winding streams, sprang up before my eyes when I pictured the locations for Gunga Jumna in my mind. In retrospect, I feel Deolali provided as much impetus to my creative thoughts when I sketched the rugged setting of Gunga Jumna’s core conflicts and dramatic scenes. I am inclined to subscribe to the belief that childhood images cling to the subconscious surreptitiously Poona gave me a sense of self-assurance and the initial opportunity to develop my character.

When the doctors felt Ayub Sahab was doing better, Aghaji shifted us back to BombayIt was not just for my education that Aghaji had to find resources. All my younger brothers and sisters had to be educated as well. The recession was setting in as I began attending high school and then Khalsa College at Matunga (a locality in central Bombay). For some reason Aghaji had great dreams for me. He wanted me to pursue my education and acquire impressive degrees.I overheard him chiding my Amma once. ‘He should not be selling fruits. He should be studying law. He must go abroad and study there. He has the potential to become somebody.’

Friendship with Raj Kapoor

I was shy and reserved by nature but I made friends easily with select college mates. At the Khalsa College I met Raj Kapoor after years. Raj’s grandfather, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor, used to visit us in Peshawar. The joy of speaking the same language, Pushtu, was itself something special for the two families.I envied Raj Raj was always at ease with the girls in the college and his extrovert nature and natural charm earned him considerable popularity. If there was anything impressive about me at that stage, it was my performance in sports and my acquaintance with English and Urdu literature.

On the field, while playing football or hockey, I was completely at ease and focused to the point of forgetting everything else.Raj Kapoor became a close pal and he used to take me to his house in Matunga where his father Prithvirajji and his demure wife kept the doors of the house open all the time I felt completely relaxed with Raj’s family. The liberal and infectiously friendly Kapoors had no hesitation whatsoever in sharing their heartiness with whoever was willing to absorb it.Raj’s younger brothers, Shammi and Shashi, were in school then. Raj had only that much interest in soccer as most others in the college. The majority of my college friends were interested in cricket and Raj, too, was more a keen cricket player than a soccer playerI remember an occasion when Raj tested my guts by telling me that a beautiful girl studying in the college wanted to be introduced to me and he pointed to one standing some distance away. He urged me to go and speak to her. There were quite a few boys and girls around us and Raj kept on urging me to walk up to her. I was extremely embarrassed and I told him I could not do that with so many eyes staring at me. He then said: ‘Okay, let us go to the canteen.’ He signalled to the girl to come to the canteen and, to my dismay, she was right there at the table that Raj was leading me to. I had to speak to her and I think she realized she would be wasting her time if she chose me to be her friend. She just got up and left after a few minutes.

Raj was determined to rid me of my shyness. One evening he came over to my house and insisted on going to Colaba for a walk on the promenade opposite the Taj Mahal Hotel. I readily agreed. When we alighted from the bus near the Gateway of India, he said: ‘Let us take a tonga ride.’ I agreed. We boarded a tonga and just when the tongawala was about to prod the horse to get going, Raj stopped him. He noticed two Parsi girls standing on the footpath. They were wearing short frocks and giggling about something. Raj craned his neck and addressed them in the Gujarati that the Parsis speak. The girls turned to him. Very chivalrously and politely he asked them if he could drop them somewhere.

They must have thought he was a Parsi, his fair complexion and good looks being such. They said they would appreciate a lift to the nearby Radio Club. He asked them to hop in. I was holding my breath in suspense not knowing what he was up to. The two girls got in and one of them sat next to Raj while the other sat next to me in the opposite seat. I made ample space for the girl to sit comfortably while Raj did nothing of the sort. He had the girl sitting very close to him and, after a minute, they were talking like long-lost friends. Raj had his hand around the girl’s shoulder and she was not in the least bothered. While I began to squirm with embarrassment, Raj was chatting away merrily.

They alighted at the Radio Club and I heaved a sigh of relief. It was Raj’s way of getting me to feel relaxed in the company of women. As Prithvirajji’s son he had an aura around him and was popular in the college campus. He knew he was heading for a profession in which there was no room for reticence or shyness. I did not have a clue about what was in store for me. All I wanted then was to become the country’s best soccer player.

The Poona interlude

The Second World War was raging and the family was going through a crisis caused by diminishing income from the fruit business, which was becoming difficult to maintain as the supply from the North West Frontier had dwindled due to strict wartime curbs on trade and transport of non-essential com- modities.I wished to be of some help to Aghaji by generating substantial income but I had no idea how I could do so.I could see that Aghaji was carrying the burden of an uncertain future in his mind and I should have not behaved the way I did on that morning. I left home with just forty rupees in my pocket, boarding a train to Poona from Bori Bunder station. I found myself seated amidst all sorts of men and women in a crowded third-class compartment. I had never before travelled third class and I hoped no one known to Aghaji had seen me at the railway terminal boarding that compartment because he was always one to give his sons the best in everything and all of us had first-class passes for our local travel.I was determined to prove to Aghaji that I could survive away from the se- curity of our home and the easy life he had provided us with. In Poona, I went first to an Iranian café, where I ordered tea and crisp khari (salty) biscuits.I spoke to the Iranian owner of the café in Persian, which made him very happy. I gingerly asked him if he knew anybody who wanted a shop assistant or something. He told me to go to a restaurant that was not far from his café and meet the owners, an Anglo-Indian couple.

It was my habit to walk briskly, so I reached the restaurant in no time. It was a quaint restaurant with its doors open for people who came there regularly, I guessed, for a good English breakfast.I spotted the couple having an animated conversation at the cash counter.I quickly introduced myself without revealing much. I referred to the Iranian café owner who had directed me to them. The lady was plump and matronly. She smiled hesitatingly through the dimples in her freckled cheeks and nudged her tall sturdy husband saying: ‘The boy speaks good English. Send him to the canteen contractor.’

Mr Welsely, as I understood his name was, looked at me carefully, paying scant attention to his wife’s recommendation, and asked me if I hailed from the North West Frontier Province. When I mur- mured in the affirmative, he told me that he knew the army canteen contractor who was a native of Peshawar and had settled down in Poona and was a much respected person. This was something I was dreading. Anyone from Peshawar would know Aghaji and that would lead to trouble for me as the news would reach him about my job hunting in Poona. Brushing aside all the wild thoughts crowding my mind, I told Mr Welsely I would be grateful if he could put in a word for me. He agreed and the next thing on my agenda was to find a place to stay, a room may be in a hotel that could give me decent comforts like a clean bed and a bathroom with hot water. I asked Mr Welsely if he could suggest such a hotel. He sent me to one that had the amenities I had mentioned.

The canteen contractor Taj Mohammad Khan had the usual awe-inspiring bearing of a Pathan and he did not ask me any questions. He gave me a sheet of paper and a pen and dictated a letter to the canteen manager request- ing him to employ me as his assistant. I took the dictation obediently and corrected the English, which betrayed his not having much familiarity with the language. He was impressed but he did not want to show it to a rank outsider, I surmised.

There was no talk of wages but I presumed it would be decent and suffi- cient to sustain myself. My job entailed several responsibilities bundled together under the head: general management.There was something fishy going on between the vendors and the manager about which I came to know by and by when I rejected some of the stuff that was of lesser quality but was being purchased at a higher price. The beer in the barrels was being mixed with buck- ets of ice and cold water to augment the quantity and I brought the matter to the manager’s attention dutifully. He advised me to overlook itI think he appreciated my feigned ignorance of his doings and, in return, he was extremely nice to me.I was extremely conscious of my hairy body, especially the hair on my hands, which would fall limp on one side when water fell over them and so would all the hair on the rest of my body. Hence, I never liked the idea of exposing my body. It is for this very reason that I have had a preference for long-sleeved shirts.

So in all fairness to the aesthetic senses of whoever might set eyes on my ape-like ap- pearance in a swimming pool, I had sensibly decided not to ever descend into one. An idea occurred to me one day when the regular chef was absent and the manager asked me if I could come up with something as a major general was having a few important guests for tea. I told him I could make sandwiches with reasonable success.Fortunately, the sandwiches were a hit. The guests of the major general praised the manager, who received the compliments smiling broadly. That was when the idea occurred to me to request him to get sanction from the contractor and the club’s office bearers to let me set up a sandwich counter at the club in the evenings.

My sandwich business opened very successfully. All the sandwiches were sold out in no timeOn the second day, I brought out a large table and covered it with white, starched cloth and laid out fresh fruits that I had selected carefully from the market along with sandwiches and chilled lemonade. The second day was a bigger success and, in less than a week’s time, I was counting the rewards When I began making money from the sandwich business, I found the courage to send a telegram to my brother Ayub Sahab informing him that I was in Poona and he may please tell Amma that ‘I am well and working in the British Army canteen’.

My telegram must have given Amma much relief.

Jailed for nationalistic views

It was wartime and there used to be discussions among the senior officers about India’s neutral stand in the war. One evening an officer asked me to give my opinion on this topic and as to why we were fighting for independence from British rule so relentlessly while we chose to stay unaligned in the war. I gave him what I thought was a good reply and he asked me if I would make a speech before the club members the next evening when the attendance would be full. I agreed and spent the night preparing my speech. I had studied the British Constitution as a student at Anjuman Islam School and put that knowledge to good use in preparing a speech that outlined our superiority as a nation of hard-working, truthful and non-violent people.

While making my speech in the club, I emphasized that our struggle for freedom was a legitimate one and it was they, the British administrators, who were consciously misrepresenting the civil laws of their Constitution and creating the consequences.

My speech evoked genuine applause and I felt elated but the enjoyment of my success was short- lived. To my surprise, a bunch of police officers arrived on the scene and handcuffed me, saying I had to be arrested for my anti-British views. I was taken away to the Yerawada Jail and locked up in a cell with some very decent-looking men, who I was told, were satyagrahis (followers of Mahatma Gandhi who offered passive resistance). On my arrival, the jailor referred to me as a ‘Gandhiwala’

In the morning, the major had come to release me and take me back. He was a good chap with whom I had played badminton when I could find time

Back to Bombay

AS THE WAR SITUATION WORSENED, SOME INEVITABLE CHANGES occurred. The office bearers of the club changed and the contractor, Taj Mohammad Khan, was replace dBy that time, I had earned a bundle of currency notes, which I counted for the first time. I had a good five thou- sand rupees, which was a great deal of money those days. I thought it was time to return to Bombay and seek a job that Aghaji would approve of or assist him in the running of the fruit business.

I was also toying with the idea of taking up a completely new line of business: feather pillows. I had made contact with a man who was ready to make me a partner and give me a substantial commission for selling such pillows to the gentry. I accepted his offer and deposited the earnest money.

After losing some money, I found out soon enough that the business of selling pillows wasn’t up my alley

Aghaji was talking to me about an apple orchard in Nainital that was on sale. He wanted me to go there and see if I could negotiate and close the deal I went there and met the owner of the orchard, a kind man who respected Aghaji and was keen to sell his land and trees to us. I could see that more than half the orchard had been destroyed by locusts and what remained was hardly worth buying. I told him we would have to negotiate the price. He said: ‘Of course, I understand.’ I had no idea what price to quote and sensing my inexperience in the business, he told me: ‘Son, I will take a rupee from you as token and we will close the deal. After you go back Khan Sahab can offer me whatever he deems good for the property.’ I returned home with the rupee and told Aghaji about the property. He was very pleased.

1942: How DK became an actor

THE TURNING POINT

ONE MORNING, I WAS WAITING AT THE CHURCHGATE STATION from where I was to take a local train to Dadar (in central Bombay) to meet somebody who had a business offer to make to me. It had something to do with wooden cots to be supplied to army cantonments. There, I spotted Dr Masani, a psychologist who had once come to Wilson College, where I had been a student for a year. Dr Masani had then given a lecture on vocational choices for arts students. At Churchgate, I went up to him and introduced myself.

He knew me well since he was one of Aghaji’s acquaintances. ‘What are you doing here Yousuf?’ he asked me. I told him I was in search of a job but since there was none in sight, I was trying to do some business. He said he was going to Malad (in the western suburbs) to meet the owners of Bombay Talkies (a movie studio) and it would not be a bad idea if I went with him and met them. ‘They may have a job for you,’ he mentioned casually. I pondered for an instant and then I joined him, giving up the idea of going to Dadar.

Though Bombay Talkies was not very far from the Malad station, he, nevertheless, took a cab to the studio since it was almost lunchtime and he was afraid that Mrs Devika Rani, the boss of Bombay Talkies, may go home for lunch. When Dr Masani entered [the office], there was warm recognition from Devika Rani who offered him a seat and looked at me wonderingly while I waited to be introduced. She was a picture of elegance, and, when Dr Masani introduced me, she greeted me with a namaste and asked me to pull up a chair and be seated, her gaze fixed on me as if she had a thought running in her mind about me. She introduced us to Amiya Chakraborthy (a famous director, as I later came to know), who was seated on a sofa. She asked me if I had sufficient knowledge of Urdu. I replied in the affirmative

She turned to me and, with a beautiful smile, asked me the question that was to change the course of my life completely and unexpectedly. She asked me whether I would become an actor and accept employment by the studio for a monthly salary of Rs 1250.So I returned her charming smile and told her that it was indeed kind of her to consider me for the job of an actor but I had no experience and knew nothing about the art. What’s more, I had seen only one film, which was a war documentary screened for the army personnel in Deolali.On reaching home I told Ayub Sahab about the offer. He found it hard to believe that Devika Rani had offered me Rs 1250 per month. He said it must be the amount she would pay annually. He said he knew that Raj Kapoor was getting a monthly salary of Rs 170. I felt Ayub was right.

The year was 1942 the prospect of earning the four-digit figure, had drawn me to a profession I knew my father had little respect for. On more than one occasion I had heard him tell Raj Kapoor’s grandfather, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor, jokingly that it was a pity his son and grandsons couldn’t find anything other than nautanki as their profession.

The next day Devika Rani welcomed me and took me personally to the floor where preparation for a shoot- ing was going on. She led me up to a man who was very well dressed and looked distinguished. He looked familiar and I recalled having seen the handsome countenance on posters and hoardings near Crawford Market. His dark hair was combed back and he smiled through his eyes at me. Devika Rani introduced me, saying I had just joined as an actor. He held my hand in a warm handshake that marked the beginning of a friendship that was to last an entire lifetime between us. He was Ashok Kumar, who soon became Ashok Bhaiyya (brother) to me.Raj Kapoorwas justly shocked to see me there.‘Does your father know?’ he asked me mischievously.

I did not reply because both Ashok Bhaiyya and Devika Rani were standing by our side and they were pleasantly surprised to learn that Raj and I knew each other. Raj gave a short account of our football days at Khalsa CollegeRaj was talking con- tenuously I thought he would give away the secret that I had joined the studio without Aghaji’s knowledge.

There was no doubt that Raj was happy to see me and welcome me into the profession.

Learning the ropes

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION!

For the first two months, Devika Rani made sure that I was present at all the shootings. Ashok Bhaiyya soon introduced me to (producer) Shashadhar Mukherjee Sahab(popularly known as S. Mukherjee), who was his brother-in-law. When he saw me, he came up to me and began talking informally as if we had known each other for years. He said he knew why I was there. ‘It is all very simple,’ he continued, as he walked with me to the door and stepped into the open area outside the studio floor. He called for chairs and the studio hands came hurriedly to attend to him.

He went on: ‘You are a handsome man and I can see that you are eager to learn. It’s very simple. You just do what you would do in the situation if you were really in it. If you act it will be acting and it will look very silly.’

There was genuine warmth in his laughter and his words gradually began to make sense to me.It was a period of transition for Bom- bay Talkies as Devika Rani, who had been managing the studio after the death of her husband and co-founder of the studio, Himanshu Rai (on 16 May 1940), was planning to marry the famous Soviet painter Svetoslav Roerich and leave the management of the studio in the hands of S. Mukherjee Sahab and Amiya Chakraborthy.

S. Mukherjee Sahab said he wanted me to meet all the writers, especially those from Bengal. ‘I want you to be there at all our story meetings and be a part of our writing teams. You have the grasp of the language that is wanting in our Bengali writers,’ he pointed out.

I thought it would be awkward for me to be participating in the discussions pertaining to the dia- logues for the stories written by such eminent directors as Amiya Chakraborthy and Gyan Mukherjee.

However, it wasn’t so. At least S. Mukherjee Sahab had made it both easy and friendly for them and me in his own genial way. My regular witnessing of shootings and my interactions with Ashok Bhaiyya were prepar- ing me for my debut. I had begun to observe Ashok Bhaiyya closely when he would be rehearsing or facing the camera. I noticed that he had made calculated movements before the camera, which he had worked out all by himself. When I got a chance to speak to S. Mukherjee Sahab alone, I mentioned my observation to him and he suggested that I go and view as many feature films as I could so that I could observe how different actors attained their levels of competence before the camera in rendering long-winded and difficult scenes.it was difficult to go straight from the studio to a cinema theatre and watch a film and go home late in the night. Besides, if someone saw me going to a theatre and reported it to Aghaji, it would raise questions in his mind because he knew I had no interest in the amusement offered by films

How Yousuf Khan became Dilip Kumar

One morning, as I entered the studio I was given the message that Devika Rani wanted to see me in her office.. She said, quite matter-of-factly: ‘Yousuf, I was thinking about your launch soon as an actor and I felt it would not be a bad idea if you adopted a screen name. You know, a name you would be known by and which will be very appropriate for your audience to relate to and one that will be in tune with the romantic image you are bound to acquire through your screen presence. I thought Dilip Kumar was a nice name. It just popped up in my mind when I was thinking about a suitable name for you. How does it sound to you?’

I was speechless for a moment, being totally unprepared for the new identity she was proposing to me. I said it sounded nice but asked her whether it was really necessary. She gave her sweet smile and told me that it would be prudent to do soWith her customary authority, she went on to tell me that she foresaw a long and successful career for me in films and it made good sense to have a screen identity that would stand up by itself and have a secular appeal.

S. Mukherjee Sahab noticed that I was rather contemplative that afternoon as we ordered lunch he asked me if there was something disturbing me and if I could share with him. I told S. Mukherjee Sahab about the suggestion that had come from Devika Rani. He reflected for a second and, looking me straight in the eye, said: ‘I think she has a point. It will be in your interest to take the name she has suggested for the screen. It is a very nice name, though I will always know you by the name Yousuf like all your brothers and sisters and your parents.’

(I later came to know that Ashok Kumar was the screen name of Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly.)

I was touched and it was a validation that cleared my thoughts then and there. I decided not to speak about the new name to anyone, not even to Ayub Sahab.

DK’s first film

Ashok Bhaiyya was a superstar now and he was delighted that I was going to be launched with a film titled Jwar Bhata to be directed by Amiya Chakraborthy. A strange truth was that I was not even slightly nervous or excited about the fact that I was going to face the camera for the first time when the D-day arrived for my first shot. I was given a simple pant and shirt to wearDevika Raniwas a great expert in make-up and knew what exactly suited the lighting of the set and the nature of the scene to be shot. She checked the light strokes of make-up given to me and asked where the camera would be placed.

She was quite satisfied with everything except my bushy eyebrows. She asked me to sit down on a chair and she called for tweezers from the make-up man and very deftly pulled off some unruly growth of straggling hair from my eyebrows to give them a proper shape while I held my breath and endured the pain it was causing. She smiled when she saw the tears brimming in my eyes as a result of the tweezing and very jovially suggested that I take a look at my face while the make-up man quickly applied some cream to ease the painful sensations on my poor eyebrows. She left after wishing me luck.

My first shot was explained to me by Amiya Chakraborthy. He made a mark on the ground and told me: ‘You will take your position here and you will run when I say “ACTION”. I will first say “START CAMERA” but that is not for you. “ACTION” is for you to start running and you will stop running when I say “CUT”.’ I asked him very politely if I may know why I was running. He replied I was run- ning to save the life of the heroine who was going to commit suicide.It was an outdoor scene and the camera was somewhere in the distance.I had been an athlete at college consistently winning 200-metre races

The shot was ready and the minute I heard ‘ACTION’, I took off like lightning and I heard the dir- ector scream: ‘CUT, CUT, CUT.’I saw him gesticulating and trying to tell me something I couldn’t figure out. I stood rooted to the spot I had reached in a flash and Amiya Chakraborthy ambled over, looking highly displeased. He told me that I ran so fast that it was a blur that the camera had captured.

It was a bit perplexing for me when he told me at first to slow my pace because I thought it was important for me to run as fast as I could and save the girl who was going to end her life. However, when Amiya Chakraborthy explained the action as something that should register on the film in the camera, which would move at a particular pace, I understood in no uncertain terms that I faced a big challenge and the business of acting was anything but simple. The shot was okayed after three or four calls for ‘CUT’.

I am often asked what I thought of my first performance and my first film, which was released in 1944.

Honestly, the whole experience passed by without much impact on me.To express love to someone completely unknown and unattached to one in reality was, at that age and time, a tough demand. I think Amiya Chakraborthy understood my predicament but he was persuasive enough to get a reasonably good output from me in the romantic scenes. When I saw myself on the screen, I asked myself: ‘Is this how I am going to perform in the films that may follow if the studio wishes to continue my services?!’ My response was: ‘No.’ I realized that this was a difficult job and, if I had to continue, I would have to find my own way of doing it. And the critical question was: HOW?

New aspirations, new experiences

I BEGAN TO VIEW MOVIES REGULARLY, BRAVING THE POSSIBILITY of being caught by someone known to my family. I must confess that the new identity as Dilip Kumar had a liberating impact on me. I told myself Yousuf had no need to see or study films but Dilip surely needed to accumulate observations of how actors reproduced the emotions, speech and behaviour of fictitious characters in front of a camera.I started getting the hang of it as I watched Hollywood actors and actresses like James Stewart, Paul Muni, Ingrid Bergman and Clark Gable but it did not take long for me to realize the essence, which was that an actor should not imitate or copy another actor if he can help it because the actor who im- presses you has consciously and even painstakingly moulded an overt personality and laid down his own ground rules to bring that personality effectively on the screen. I understood very early on, while I was at Bombay Talkies itself, following such films as Milan (1946), that I had to be my own inspiration and teacher and it was imperative to evolve with the passage of time.

It was also wonderful to be in the company of Raj Kapoor again after our Khalsa College days. Raj was happy to know I had seriously entered the profession of film acting. ‘I told you, didn’t I?’ he said, hugging me like a little, excited boy when I was ready for my debut. When we were at Khalsa he used to tell me in Punjabi: ‘Tusi actor ban jao. Tusi ho bade handsome.’ (You should become an actor. You are very handsome.)

As 1945 rolled by, the Second World War was coming to an end and the freedom movement was gain- ing momentum in the country. At the studio every day, Ashok Bhaiyya and S. Mukherjee Sahab would engage in discussions about what they had heard or read. They would seriously discuss Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s speeches and ask me for my opinion. Having had a ‘memorable’ experience when I spoke my mind at the Wellington Soldiers Club in Poona, I thought it best to maintain a discreet silence. By the time I finished my work in Jugnu, our country was heading for its emancipation from British rule. I remember the day – 15 August 1947 – vividly when independence was won for us by the great men and women who fought for it tenaciously and relentlessly for decades. I was walking on the pave- ment near the Churchgate station, quite unnoticed despite having acted in three films – Jwar Bhata (1944), Pratima (1945) and Milan (1946) – when I noticed people were rushing homewards with joy- ous expressions on their faces. It was only when I reached home and I saw the whole family together for a change with every face shining with happiness that I realized it was independence day.

1947: Aghaji discovers his son’s secret profession

Jugnu was released in late 1947.

The film became a hit and the hoardings were put up in many places, including a site near Crawford Market. One morning while Aghaji was supervising the unloading of a consignment of apples at his wholesale shop in the market, Raj’s grandfather, Basheshwarnathji, walked in and the two greeted each other warmly as always.

That morning Basheshwarnathji had a naughty smile playing beneath his moustache. He twirled his moustache and told Aghaji he had something to show him: something that would take his breath away. Aghaji must have wondered what it could be. Basheshwarnathji took him out of the market and showed him the large hoarding of Jugnu right across the road. He then said: ‘That’s your son Yousuf.’

Aghaji told me later on that he could not believe his eyes for a moment but there was no mistaking me for someone else because the face he knew so well was printed large and the blurb on the hoarding was hailing the arrival of a bright new star on the silver screen. The name was not Yousuf. It was Dilip Kumar.

He described to me much later, after he accepted my choice of career, the awful feeling of disappointment that overwhelmed him at that moment. He was naturally very angry. Aghaji did not reveal his anger and hurt pride through harsh words or any other form of resentment.

He was very quiet for some days and did not speak to me. Even at other times, when we spoke to each other in monosyllables, I did not dare to look him in the eye. Soon, the situation became awkward and I did not know what to do.

The thick layer of ice had to be broken somehow. I confided in Raj and he said he knew this was going to happen and the best person to mediate was Prithvirajji. And he was right. Prithvirajji paid a casu- al visit to our home one day. Amma told me when I got home in the evening that the powwow with Prithvirajji had done considerable good and she noticed that Aghaji was a lot more relaxed and cheerful. == Filmistan and Shaheed (1948) BETWEEN THE PERSONAL AND THE PROFESSIONAL

My contract with Bombay Talkies was coming to an end and there were changes taking place in the stu- dio management. Ashok Bhaiyya had moved out and so had S. Mukherjee Sahab to form Filmistan. As we were no longer fettered by foreign rule, there was a surge of creative activity and spirited unravelling of the communicative powers of the medium. Movies were being made with a sense of introspection, patriotism and social purpose by many talented and dedicated film makers.

I did not hesitate to accept S. Mukherjee Sahab’s invitation to work in the pictures to be made at Filmistan. The beneficial aspect was that he did not talk about a contract or agreement restricting me to work only in his pictures. As it was, the studio employment system was inevitably being replaced by managements seeking services of actors and technicians on a freelance basis with varying remuner- ations commensurate with experience, expertise and track record.

There were many producers who had noticed me then and had called me over to talk about the films they were proposing to make with me in the male lead. S. Mukherjee Sahab was aware of this development and he respected my decision to work in his venture at Filmistan. The film was Shaheed (released in 1948).The subject fired my imagination and I felt it was a wise decision to make a patriotic film .

I was completely in synch with the character in Shaheed because of the social and political climate prevailing at that time and my own patriotic senti- ments were seeking an outlet, which was there for the asking in the well-written scenes and dialogues.

Though the film was directed by Ramesh Saigal, it was the inspiration we got from S. Mukherjee Sa- hab that fleshed out the performances and added momentum to the movement of the narrative.

Kamini Kaushal

Kamini Kaushal had a noticeable fluency in speaking English, which was unusual those days for an act- ress and that delighted S. Mukherjee Sahab who generally preferred to talk in that language. In fact, after a day’s intense work on scenes that called for serious emoting, we formed a small circle for some nice light-hearted conversation, in which occasionally Ashok Bhaiyya also joined. Ramesh Saigal was a good conversationalist and he was the first one to address Kamini Kaushal by her real name Uma (Kashyap) and all of us followed suit.

Shaheed met with deserving success at the box office. My pairing with Kamini Kaushal in that film got an encore from the audiences and Filmistan had us teaming up in Nadiya Ke Paar (released later in 1948) and Shabnam (1949), which became even bigger successes. As far back as the 1940s, the gimmick of pleasing the mass audience by bringing together artistes [in this case Dilip Kumar and Kamini Kaushal] who were believed to share an attraction for each other in the life they lived outside their work environment was as common as it is today.

Stardom bothered me more than it pleased me and I guess I was drawn more intellectually than emotionally to Uma, with whom I could talk about matters and topics that interested me outside the purview of our working relationship. If that was love, may be it was. Yes, circumstances called for us to discontinue working together and it was just as well because, after a few films together, star pairings generally tend to pall on viewers, which is bad for business.

A question I have often been asked is the somewhat intrusive one whether it makes a difference to the potency of the emotions drawn from within oneself in an intimate love scene if the actors are emotion- ally involved in their real lives. My honest answer is both yes and no.

Shifting home to Pali Mala, Bandra

It became imperative now for us to shift our residence to a suburb that was closer to Goregaon (in western Bombay), where many film studios were (and are) situated.Aghaji agreed to shift to Bandra (also in western Bombay). We took a bungalow at Pali Mala in the midst of a cluster of dwellings owned by Goan Christian settlers.

I bought a Fiat car (sometime in the late 1940s) not so much because I needed it but more because my sisters required a vehicle to go out. My first drive was to the Brabourne Stadium. A cricket match was going onI picked up Dr Masani and we reached the stadium in time to be ushered to the enclosure meant for special inviteesI found myself seated beside an impressive looking man wearing an unbuttoned jacket over his shirt. He was talking to a lean man seated on his right, tilting his broad frame to hear what the lean man was trying to tell him on seeing me. I took my seat and since both of them smiled at me I thought it fit to greet them. They were ob- viously my co-religionists because they were in the Muslims’ enclosure, so I said ‘Salaam Alaikum’ (peace be upon you), and they returned my greeting warmly.

After the match started and progressed, the impressive looking man felt he should speak to me. He introduced himself as Mehboob Khan and introduced his friend as Naushad Miyan. It was the begin- ning of two enduring friendships and professional relationships in my life and career. Naushad Miyan (basically a music composer) had written the story of what became the film Mela and he invited me to meet him and the director, S. U. Sunny, the following week. Both Naushad Miyan and Mehboob Khan had seen Shaheed.

My meeting with Naushad Miyan took place in Sunny’s small office where he narrated to me briefly the story of Mela. He also told me that they had recorded the title song with which they would like to start the shooting. It was a bit awkward for me to ask questions about the details of the story but I thought it would be a risk if I did not know enough to be in a position to accept the film.

DK’s ground rules as an actor

I must mention here that my work choices from the very beginning were not governed by the remu- neration I was offered.

This was something I learned from Nitin Bose and Devika Rani who were my first and most influential teachers. While working with Nitin Bose during the making of Milan (1946), I understood how vital it is for an actor to get so close to the character that the thin line between the actor’s own personality and the imagined personality of the character gets ruthlessly rubbed off for the time when you are involved in the shooting. To get that close to the character it is very important to know everything about the character and his mind and emotions.

While I was deeply involved with Milan, one day Nitinda asked me whether I had seriously read the novel Nauka Dubi (written in Bengali by the Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore). I told him that I had read the translation given to me and, of course, the script, which was very detailed. We were pre- paring to shoot the scene in which the character named Ramesh has travelled all night by train and has reached Varanasi (now in Uttar Pradesh), where he has to immerse the mortal remains of his mother in the Ganga. He performs his duty with a heavy heart, tired and weather-beaten as he is bound to be after the overnight journey. Nitinda asked me if I had given sufficient thought to the state of Ramesh’s mind and his feelings during the journey by train sitting up all night holding the urn securely so that the last remains from it did not spill out. Nitinda also asked me to think over the scene, imagining the disturbed state of Ramesh’s mind as he sat looking at the urn and remembering his mother who used to talk to him affectionately and serve him food and wake him up in the mornings with a cup of hot tea.

He finally asked me: ‘Don’t you think Ramesh would have thought to himself, this is my mother who has been reduced to ashes, my mother who had such soft hands and such gentle eyes?’ I told Nitinda frankly that I had not thought so deeply because such depth was not in the script. Nitinda of course understood but he gave me a valuable lesson that has stood me in good stead. He made me write four to five pages expressing my feelings as Ramesh during the journey. I sat up half the night and wrote and rewrote until I was overcome by sleep.

The next day the scene was to be shot at a location in Ghodbunder in Bombay. When the camera started to roll I was into the scene emotionally and the ex- perience was satisfying for me and Nitinda.

That was how Nitinda groomed me. He explained that a good script always helped an actor to per- form effectively but there were areas beyond what was given to him in the script that were waiting to be explored by one who wished to rise above the given areas in his performance.Devika Rani had advised me and all the actors she employed at Bombay Talkies that it was important to re- hearse till a level of competence to perform was achieved. In the early years, it was a necessity for me to rehearse, but, even in the later years, her advice stayed with me when I had to match a benchmark I had mentally set for myself.In fact, I am aware that I am known for the number of rehearsals I do for even what seems to be a simple scene.

Let me give an example. There was a situation in Nitin Bose’s Deedar (1951), in which Ashok Bhaiyya and I had lines to deliver and the cue for his lines had to be taken from my lines. In our re- hearsals we had mutually decided that the word ‘mulayam’ (meaning soft) in my dialogue would be his cue to speak and turn his face towards me. Being a Bombay Talkies man, Ashok Bhaiyya had as much of a fetish for rehearsals as I had and so we had already had almost eight to ten rehearsals. The director told us to be ready for the take and he called for action. When I spoke my dialogue, quite in- advertently, I replaced the word ‘mulayam’ with ‘narm’ (also meaning soft) and Ashok Bhaiyya was thrown off track. I don’t know what went wrong with me that day. The director called: ‘CUT’; and I need not tell you what followed. Though not one to lose his temper, Ashok Bhaiyya gave me a piece of his mind and said gruffly: ‘OK, now we will stick to “narm”.’

Mashaal (1984): the genesis of the Ai bhai scene

It was typical of Aghaji [Dilip Kumar’s father] to pretend to be unemotional and detached. His warmth and concern surfaced only once when Amma had a serious attack of asthma and she was choking and gasping for breath. He began yelling for someone to rush and fetch the doctor who lived across the street. His face was then a picture of helpless alarm and I still can recall the tall strapping figure bending to hold my frail Amma in his arms.

If you can recall the famous scene in Mashaal, I must tell you that, while going through my re- hearsals, I drew my emotions for the rendering of the scene, shot over four nights in a row, from the memory of that episode and the agony of Aghaji in his urgency to get instant medical help. [*Film maker Yash Chopra’s Mashaal (1984). The scene depicts me on a rainy night desperately seek- ing help to take my seriously ill wife (played by Waheeda Rehman) to hospital by trying to stop any vehicle that comes along, but in vain.]

The women Dilip Kumar really loved

Dilip Kumar fell in love for the first time with renowned actress Kamini Kaushal. It was on the sets of ‘Shaheed’ that their love blossomed. They were planning to marry as well, but Kamini's brother was against the relationship. Since, Kamini was already married to her late sister's husband to look after her child; it was difficult for her also to move out. It is also said, that Kamini’s brother even threatened the actor to break off and move on.