Education: India

This article has been sourced from an authoritative, official readers who wish to update or add further details can do so on a ‘Part II’ of this article. |

Contents |

Part I

The ministry's overview

The source of this section

INDIA 2012

A REFERENCE ANNUAL

Compiled by

RESEARCH, REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION

PUBLICATIONS DIVISION

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

EDUCATION is not only an instrument of enhancing efficiency but also an effective

tool of augmenting and widening democratic participation and upgrading the

overall quality of individual and society. India has a vast population and to capture

the potential demographic dividend, to remove the acute regional, social and gender

imbalances, the Government is committed to make concerted efforts for improving

the quality of education as mere quantitative expansion will not deliver the desired

results in view of fast changing domestic and global scenario.

Before 1976, education was the exclusive responsibility of the States. The Constitutional Amendment of 1976, which included education in the Concurrent List, was a far-reaching step. The substantive, financial and administrative implication required a new sharing of responsibility between the Union Government and the States. While the role and responsibility of the States in education remained largely unchanged, the Union Government accepted a larger responsibility of reinforcing the national and integrated character of education, maintaining quality and standard including those of the teaching profession at all levels, and the study and monitoring of the educational requirements of the country.

The Central Government plays a leading role in the evolution and monitoring of educational policies and programmes, the most notable of which are the National Policy on Education (NPE), 1986 and the Programme of Action (POA), 1986 as updated in 1992. The modified policy envisages a National System of education to bring about uniformity in education, making adult education programmes a mass movement, providing universal access, retention and quality in elementary education, special emphasis on education of girls, establishment of pace-setting schools like Navodaya Vidyalayas in each district, vocationalisation of secondary education, synthesis of knowledge and inter-disciplinary research in higher education, starting more Open Universities in the States, strengthening of the All India Council of Technical Education, encouraging sports, physical education, Yoga and adoption of an effective evaluation method, etc. Besides, a decentralised management structure had also been suggested to ensure popular participation in education. The POA lays down a detailed strategy for the implementation of the various policy parameters by the implementing agencies.

The National System of Education as envisaged in the NPE is based on a national curricular framework, which envisages a common core along with other flexible and region-specific components. While the policy stresses widening of opportunities for the people, it calls for consolidation of the existing system of higher and technical education. It also emphasises the need for a much higher level of investment in education of at least six per cent of the national income.

The Government has taken/proposed a number of major initiatives during the 11th Five Year Plan. Some of the new initiatives in the School and literacy sector and Higher and Technical Education sector include: Right of Children to free and Compulsory Education Bill, Launching of Saakshar Bharat, ICT in Secondary Schools and in open/distance schooling, Evolving a National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education, Examination reform in accordance with NCF-2005, introducing a System for replacement of marks by grades at the Secondary stage in schools affiliated to CBSE, Recommendations of Yash Pal Committee and National Knowledge Commission, Establishment of 14 Innovation Universities aiming at World Class Standards, Setting up 10 new National Institutes of Technology,

Launching of new Scheme of Interest subsidy on education loans taken for professional courses by the Economically Weaker Students, Scheme of setting up of 374 Model degree colleges in districts having gross enrolment ratio for higher education less than National GER, 150 women's hostels in higher educational institutions located in districts with significant population of weaker sections and minorities, Academic Reforms (Semester system, choice based credit system, regular revision of syllabi, impetus to research), etc.

In order to ensure all-round development in the field of education, the Ministry of Human Resource Development was created on 26 September, 1985. Currently, the Ministry has two Departments namely: (i) Development of School Education and Literacy which deals with Elementary, Secondary and Adult Education or literacy. (ii) Department of High Eduction which deals with university Higher Education, Technical Education, Ministry Education, Scholarship, languages, Book promotion of copyright.

In line with the commitment of augmenting resources for education, the allocation for education has over the years increased significantly. The Plan outlay on education was Rs 151 crore in the First Five Year Plan. The 11th Five Year Plan (2007-12) is Rs 2,69,873 crore, an increase of more than 9 times than Xth Plan. Of which Rs 84,943 crore is for the Department of Higher Education and Rs 1,84,930 crore is for the Department of School Education and Literacy.

UNESCO's Education Monitoring (GEM) report, 2017

Unesco Report Also Says 266M Adults Can't Read

Right from 1 million rural medical practitioners who are not graduates of accredited schools to 41% of the schools in the country not having gender-specific toilets, Unesco's latest Global Education Monitoring (GEM) report has highlighted the major challenges India faces in achieving global education goals.

The report, released globally on Tuesday , revealed that despite significant success, India needs to take note of the big gaps -especially how, even now, 2.8 million children are out of school, 11 million out of lower secondary school and 47 million out of upper secondary school.It has also suggested better regulation of private tutoring, of which even HRD minister Prakash Javadekar is critical, as the industry is poised to be worth over $200 billion by 2020 globally and is seen as a practice widening the education gap between the rich and the poor.

The report says Unesco Institute for Statistics data shows a quarter of India's children are not completing their lower secondary education and that there are 266 million adults and 33 million young people unable to read.

The report “Accountability in Education: Meeting Our Commitments“, while emphasising that accountability starts with government, highlights the fact that India's spending on education financing is below global benchmarks -3.8% of GDP to education (not 5%) and 14% of public expenditure on education (not 15%).

The report also cites some im pressive Indian successes with several programmes aimed at improving gender equality . “The curriculum for Gender Equity Movement in Schools, aimed at girls and boys aged 12 to 14 (grades 6 to 8), focused on gender, relationships, violence and emotions. Participation helped increase recognition of various forms of violence and led gradually to fewer incidents and more reporting of physical violence,“ it adds.

Part II

Access to education

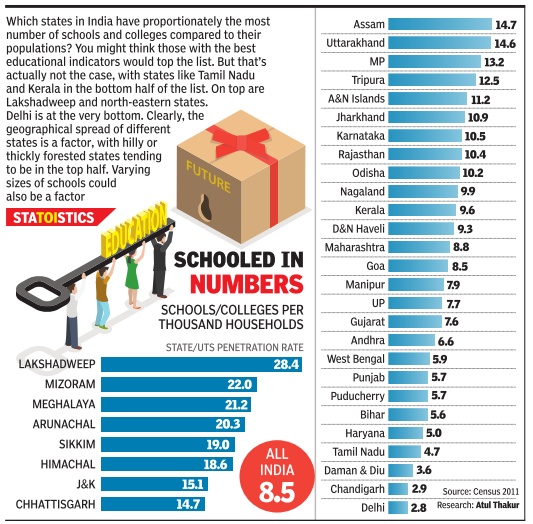

Schools, colleges per thousand households, 2011

See graphic, ‘Schools, colleges per thousand households’

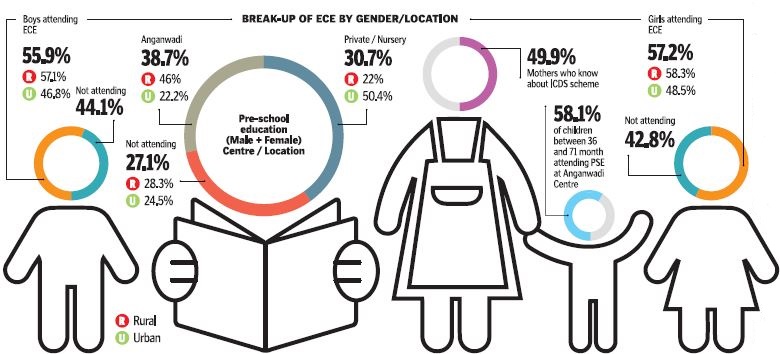

Childhood (early) education

2011

The Hindu, December 16, 2016

G. Krishnakumar

The absence of a strong regulatory framework remains a key challenge to ensuring quality of ECE programmes nationwide

Across India, a lack of effective regulation appears to be eroding the overall quality of Early Childhood Education (ECE).

ECE holds the key to every child’s lifelong development, as neuroscience research has found that the experience of the infant and young child provides the foundation for long-term physical and mental health along with cognitive development.

As per the Census 2011, India has 158.7 million children in the 0-6 years’ age group. The National Early Childhood Care and Education policy, adopted in September 2013, stated that there was no reliable data available on the actual number of children benefiting from Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE). Nor was there clarity on the breakup of the types of services delivered despite the existence of multiple service providers.

Estimates by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in 2011 showed that about 76.5 million children (48.2 per cent) were reported to be covered under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), which has ECE as one of its six components, in addition to health and nutrition. The ECCE policy accepted that the unregulated private channel, both organised and unorganised, is perhaps the second largest service provider of ECCE, and its outreach is steadily spreading even to the rural areas across the country although with varied quality.

This channel suffers from issues of inequitable access, uneven quality and growing commercialisation, it said.

Preferred choice

Findings from the Indian Early Childhood Education Impact Study (survey of ECE centres in Andhra Pradesh, Assam and Rajasthan) by the Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development (CECED) under the Ambedkar University, Delhi, showed that “private pre-schools are emerging as the preferred choice of parents for ECE with most parents perceiving these to be better quality, for which they are also willing to pay a fee”.

“But our assessment of the quality of these community-preferred private ECE centres shows that they are not necessarily providing the recommended age and developmentally appropriate pre-school curriculum to young children,” says Professor. Venita Kaul, Director of CECED.

However, the aspirations of parents have gone up and they believe that sending children to private schools would offer quality learning.

Interestingly, researchers pointed out that both private and anganwadi models demonstrated lack of developmentally appropriate curricula, with the focus being either on teaching of reading, writing and arithmetic, rather than providing a strong conceptual and cognitive foundation and development of the child.

A decline in the qualification and training levels of teachers in private pre-schools and anganwadis continues to be a major concern.

Ensuring quality of the ECE programme remains a key challenge before the Centre, especially in view of the absence of a strong institutional mechanism and a regulatory framework across sectors.

Enrolment

2001-11: Number of students up 38%

The Times of India, Aug 30 2015

Subodh Varma

Number of students up 38% in 10 years, shows census

Population rose 18% in same period

In the space of a decade, between 2001 and 2011, the stu dent population in India ex ploded from about 229 million o 315 million. That's a jump of nearly 38%. The overall population growth in the same period was 18%. But Census data released on Friday underscores a much bigger shift within these gross figures. Students in the age group 15 to 19 years increased by a dramatic 73% in the decade, rom 44 million to over 76 mil ion. This age group pertains to students at senior secondary and post-school higher education levels. So, the mas sive increase in student populations is being driven by a spectacular growth in higher classes, with women students eading the charge.

“There is a deep hunger or education in India today that never existed at this mass scale earlier. Education is seen as a sure path towards economic wellbeing,“ explained Jayan Jose Thomas, professor at IIT Delhi who has been studying education and employment in India. “The question looming in front of us now is whether suitable jobs can be given to all these educated people,“ he added.

The new Census data also reveals the flip side of this student growth -those who are left behind. Nearly one in 5 of all seven-year-old children had not yet entered school. That's about 4.8 million kids. By age 13, this proportion had come down to about 7% of that age. That is, about 1.6 million children had still never entered school.The trend is for children to enter school late and for some to never get any schooling.

Over 308 million Indians, making up about 25% of the population of age 5 years and above have never attended any educational institution. But this is a legacy of the past -nearly three quarters of them (72%) are 25 years or older.

Thomas has analysed the data coming from NSSO to see how exactly this student population explosion happened between the Census years of 2001 and 2011. Student enrollment in the 5-9 and 10-14 years age groups increased substantially between 1996 and 2004-05 driven by the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, various Supreme Court directives regarding mid-day meals etc. After 2004-5, the enrollment among 15-19 years age group has risen consistently as shown by NSSO data analysed by Thomas.

Interestingly, Thomas finds that the gap between rich and poor in terms of education for the whole 5 to 24 years age group has come down over the years. This means that the poorer sections are also eager to get educated and may be willing to make economic sacrifices in order to get their children educated, as far as possible.

But there is one gap that is still not coming down in India -the regional imbalance.As the Census 2011 data shows, enrollment in the 15 to 19 years age group varies widely across states with Kerala having the highest student share of 83% and Odisha at the other extreme with just 43% enrollment.

Surprisingly , West Bengal and Gujarat are also in the bottom league with 53 and 51% student shares in the 15-19 years age group. This reflects on the availability of higher education options in the state.More industrialized and urbanized states like Maharashtra Haryana and Tamil Nadu are among the states with higher student shares.

Muslim, SC, ST, OBC enrolment

Muslim enrolment goes up in schools: HRD report

New Delhi TIMES NEWS NETWORK

The Times of India Jun 19 2014

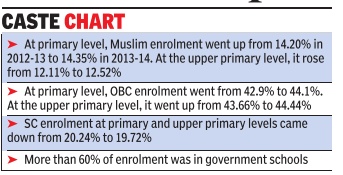

Muslim enrolment in schools has gone up marginally while there has been a slight decline in case of the SC/ST community . Children belonging to Other Backward Classes (OBCs) have shown a perceptible increase in enrolment.

Data for 2013-14, released on Wednesday by HRD minister Smriti Z Irani, shows that as per the Educational Development Index, Puducherry is at number one, followed by Lakshadweep, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi.

Despite massive privatization of school education, more than 60% of enrolment was in government schools, just over 8% in private aided schools, 27.8% in private unaided schools, 35.81% in private managements and over 2% in unrecognized schools.

Government-aided schools with private management dominated in Goa (63.03%), Kerala (42.36%) and Maharashtra (37.8%). Muslim enrolment at primary level went up marginally to 14.35% in 2013-14 from 14.20% in 2012-13. At the upper primary level, enrolment was 12.52%, up from 12.11% in the previous year.

In West Bengal, Gujarat, Bihar and UP, there was a gradual, although not significant, increase in enrolment. Enrolment of girls, both at primary and upper primary levels, remained unchanged at 49%.

At the primary level, OBC enrolment has gone up to 44.1% from 42.9%, while at the upper primary level, it went up to 44.44% from 43.66% in 2012-13. The most perceptible increase can be noticed in West Bengal, Puducherry and Kerala. Girls constitute nearly half of the new enrolments, at both primary and upper primary levels.

Enrolment of SC children at primary and upper primary levels came down to 19.72%, from 20.24% in 201213. Except for Himachal Pradesh and West Bengal, a marginal decline in SC enrolment can be seen in most states, especially Bihar, UP, MP and Maharashtra.

The percentage of teachers involved in non-teaching assignments to the total number of teachers has come down from 5.49% to 2.48%.

Government’s measures

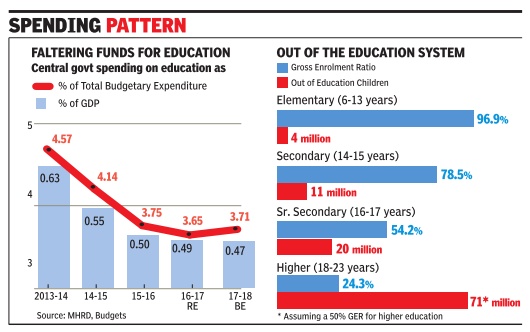

Govt expenditure on education

2014-17: Decreases as %age of govt. budget

Outlay Down From 4.57% Of Budgetary Expenditure In FY14 To 3.65% In FY17

Spending on education as a share of the central gov ernment's total budgeted expenditure has been falling for the past three years. Compared to 2013-14, the last year of UPA, when education got 4.57% of the total expenditure, there has been a steady decline -3.65% in 2016-17, according to this Budget's revised estimate, with the estimated outlay for the coming year showing a minor uptick at 3.71% (see accompanying table).

Looking at education spend as a share of the GDP, which is what international trackers do, the trend is clear -having dipped from 0.63% of the GDP in 2013-14 to 0.47% projected by the government for 2017-18.

Although budgeted expenditure for the ministry of human resource development (MHRD) has been increased over the previous year by about 8%, this is illusory because inflation of about 5-6% would neutralise most of it.Since 2016-17, the government has rejigged the sharing pattern of central schemes in key sectors, including secondary and higher education, with lower outlays in the Budget and more direct transfers in keeping with the 14th Finance Commission's recom mendation. This would have marginally contributed to a decline in the total education outlay as allocation for two schemes concerning secondary and higher education -the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan and the Rashtriya Uchchtar Shiksha Abhiyan -was about 7% of the total education outlay in 2015-16, the last year before new sharing pattern.

These are not mere numbers. Their importance for India lies in that public spending on education is a must for making it available for all, and in better quality . While government policymakers since UPA's times have been congratulating themselves for bringing almost all the children aged 6-13 years to elementary school, little attention has been paid to the fact that after this stage, it is downhill all the way . Gross enrolment ratios (number of students in school at a particular stage as a percentage of all children in the concerned age group) rapidly deteriorate after elementary school, going down to just 54% by senior secondary level. In other words, roughly half the children are out of school by the time they are senior school age. This works out to about 35 million kids out of school.

In higher education, the situation is much worse, with an enrolment ratio of just 24% for the 18-23 age group. This includes distance education students. In most advanced countries, the ratio is close to the 50% mark. So, about 71million youth are still out of the higher education system. Enrolment ratios are lower for Dalits and Adivasis, and dropout rates higher. So they need to be reached out to, especially in remote areas. School infrastructure and teachers need to be provided for. NGOs and corporate bodies can't handle this.But the government has made an increase of only 4% for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan.

The problem does not end here. Even after getting everybody into school and college, there's need for good, qualified teachers. At present there are about 8.6 million school teachers and 1.5 million higher education teachers in the country . So, India needs to prepare teachers through well-equipped training colleges. But where are the funds for that? Here's another problem: The Right to Education Act, implemented since 2010, mandates certain basic norms like pupil-teacher ratio and physical infrastructure. One study has shown that only about 10% of the schools fulfil all the norms. Bringing up the other schools to the RTE standard will demand enormous funds.

As it is, the India's education system is creaking at the seams, family spending on education is rising, quality is speedily deteriorating, and a quarter of students are dependent on private tuitions for getting through. If the system is starved of cash, it could well be a disaster in the making.

Unified District Information System for Education

The Times of India, Jul 03 2016

Akshaya Mukul

It could be curtains for more than two-decade old Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE) through which the official school education data is maintained in the country .The responsibility of compiling data will be passed to the National Informatics Centre.To begin with, NIC will be involved in government's Shala Asmita Yojna (SAY) that will have a ready database of 25 crore schoolgoing children and eventually be the repository of official school data. The decision has come as a shock to the National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA) under which the U-DISE functions. In fact, U-DISE is formally the repository of all official statistics on school education used by everyone, from policy planners to Unicef. In early May , in the meeting of the project approval board in the HRD ministry , NUEPA was asked to compile student-wise data collection for SAY. But last week, the HRD ministry finally decided that NIC will do data collection for SAY. However, a section of school department in HRD was not in favour of cutting off links with NUEPA.

Aware of the criticism that U-DISE has got in the National Education Policy report, NUEPA says it is willing to take corrective measures. “There have been cases of over-reporting school attendance as well as fake data. Student-wise data will help. We have everything including a mobile app for student-wise data collection. How can NIC start from scratch? We have helped states that collect student-wise data,“ a senior NUEPA official said. HRD sources say that the U-DISE will not stop immediately but will be slowly phased out.

On its part, NIC is not prepared for the massive task. A senior NIC official said, “We have the technical knowhow but collecting data of 25 crore school going children will need creation of a big infrastructure and induction of experts who know about school education. It will be difficult to meet February deadline for SAY.“

Report on National Education Policy had pointed out that DISE data in many states may not be reliable.

Out-of-school children (OOSC)

Dropout levels

The Times of India December 17, 2014

Dropout rate remains high among girls

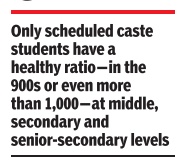

Government schemes and programmes designed to help girls continue in school aren't working. At the primary level, the number of girls per 1,000 boys has fallen from 881 in 2010-11 to 867 in 2013-14. At the secondary school level, it has fallen from 859 in 2010-11 to 840 in 2013-14. Only scheduled caste (SC) students have a healthy ratio--in the 900s or even more than 1,000--at middle, secondary and senior-secondary levels. R Govinda, vice-chancellor, National University for Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA), however, doesn't see it as a failure of government schemes and policies, or even a long-term trend. He says enrolment at the primary level increased tremendously after Right to Education Act was imple mented in 2010. “It'll take a few years for that change to show up in the statistics.“

Govinda says more girls than boys drop out after finishing primary and middle levels, but those who enter secondary school usually stay on till the end. That isn't the case with boys, which may explain the increase in sex ratio from secondary to senior-secondary. In 2010-11 the sex ratio was 859 at secondary level and 881 at senior-secondary level; in 2013 14, it declined to 840 at the secondary level but increased to 896 at the senior-secondary level. This is not because of greater participation of girls but because boys have started dropping out by this stage.

“In Delhi, boys start dropping out when they move from municipal to government schools,“ says Saurabh Sharma of Josh, a city NGO that is also part of the Right to Education Forum. “For five feeder municipal schools, there will be one government school. In that crowding, boys find it very difficult to survive. They may get out and start working.“ He says the problem is shortage of schools, not resistance from parents. He disagrees with Govinda on the effectiveness of government schemes. “Most parents don't even know how to apply for Ladli. There's no one to tell them what to do.People have no faith in schemes,” says Sharma.

Why do SC students have a better sex ratio? Sharma can't explain that one. “Does this mean SC parents are more aware? I don't think so.“ Govinda says it could be because SC boys and SC girls drop out equally . The figures bear this out but only for 2010-11 when 12,747 boys and 13,836 girls transitioned to senior-secondary from 17,188 boys and 17,650 girls who were in Class X, and the sex ratio remained over 1,000. In 2012-13, the number of SC students increased from 77,470 in secondary to 81,853 in senior-secondary.

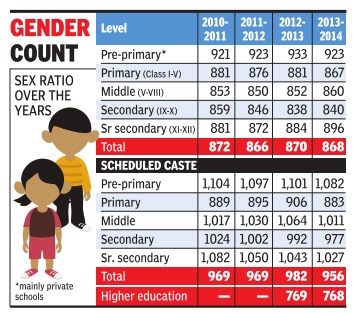

Delhi’s special training centres for working children

Shreya Roychowdhury, Helping kids left out to get back to school Oct 07 2016 : The Times of India

STCs Mainstreaming Kids Who Also Work

Children attending the special training centre (STC) in Rana Pratap Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya, Rithala, were out-ofschool and working till April, 2016. A sizeable section of them still works in the evenings and contribute towards the family's “rozi-roti.“ Their teacher is trying to get this lot of 33 kids 15 girls and 18 boys aged 7-10 ready for regular school by the end of this academic year.

At present, Delhi has 166 STCs to run bridge courses for out-of-school children (OOSC) -122 in government schools. By August 2016, they'd collectively enrolled about 6,000 less than a tenth of the total number of OOSC the Directorate of Education (DoE) now estimates there are in Delhi. Preliminary findings in a ward-level headcount indicate their number could even be a lakh. The DoE intends to ask each school municipal and government -to start one STC, raising their number to over 2,500.

Delhi's Census 2011 figures show that 64.93% OOSC aged 7 show that 64.93% OOSC aged 714 were “non-workers.“ But nearly everyone in Jyotsana's class picked waste before joining; many 11 of 28 kids present on Thursday -still do. “We go in the evening now,“ says Tufan, 10. Lucy and Khushboo add that they make about Rs 100 each. Even the ones not stepping out of home, aren't free to be just kids. Mehboob, 10, is frequently kept at home by his parents a rickshaw-puller and a domestic help to mind his two-year-old brother. Till the STC happened, “ghar sambhalna (managing home)“ was Rupali's full-time job.

With so many responsibili ties claiming their time, retention is a challenge. Jyotsana makes “home-visits“ to coax kids out. There's attrition due to migration. “Numbers usually reduce. Last year, about 60%70% of the class was mainstreamed,“ says Manju Kochhar, principal, RP-SKV .

The Right to Education Act 2009 provides for STCs; the Delhi Rules require a programme to run for a minimum of three months to two years. A few in every batch become class-ready and are mainstreamed before the year is up. “ About 10 in a batch,“ says teacher Jyotsana. Most are 7-year-olds, less behind their peers than older OOSC. The course, designed by the State Council for Education Research and Training (SCERT), covers mathematics, Hindi, English and EVS.

In addition to handling the deficit in academic achievement, teachers also ensure the school culture is understood not leaving the classroom randomly , sitting in order, coming in uniform. Parents, mostly unschooled, need as much pri ming. Jyotsana's lot has settled in; some are even ambitious.Raja hopes to be a doctor; a few, engineers. But coming from areas where theft is common and residents generally vulnerable, most girls and boys want to be in the police.

Kochhar had initially been reluctant to set up a STC. “I have about 3,600 students and space is limited,“ she says, “We managed one room from the evening-shift. Even that hasn't been fully cleared.“

Space, DoE officials concede, is a problem. “Some schools seat over 100 kids in a room,“ says E Raja Babu, state project director, SSA, “ Allocating a room for STC will be difficult.“

The government is considering partnering with more NGOs. “The NGO-run ones aren't functioning well because most funds go into paying for utilities,“ explains Babu“

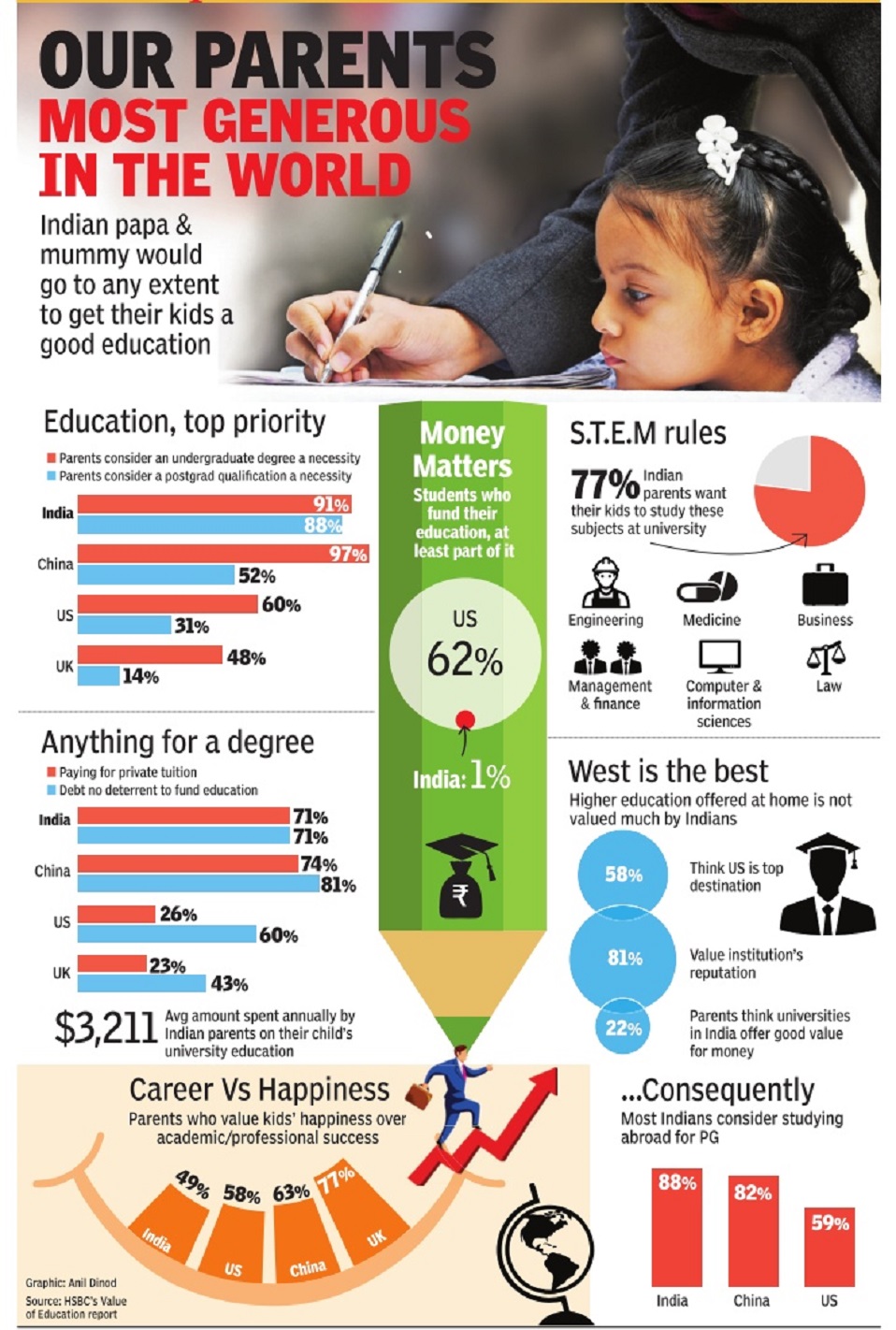

Paying for education

Indian parents pay for college, private tuition

The Times of India

See graphic, In India parents pay for children's education

Sports quotas

Hyderabad HC declares them illegal

The Times of India, Aug 18 2016

SagarKumar Mutha

The Hyderabad high court has called upon state governments across India to consider dissolving the sports quota for admission in educational institutes, saying it provided a backdoor entry to students who were not meritorious. The quota does not have constitutional sanction either, it added. In an order dated August 8, a copy of which was made available only on Wednesday, the HC also criticised the Andhra Pradesh government for including “insignificant“ games under the sports quota. “It is sad to note that except video games, all other games that one could conceive of have been brought within the sports quota to enable persons who cannot excel in studies to gain admission into medical courses through the backdoor,“ a bench of justices Ramasubramanian and Anis said.

The court thus dismissed a petition filed by a student challenging NTR University of Health Sciences' decision to not consider her for an MBBS seat under the sports quota stipulated by an Andhra Pradesh government order that included six more games in the quota apart from the 28 added since 2008.

The six new games are: tennikoit, powerlifting, netball, throwball, sepak takraw (kick volleyball) and boxing. Holders of merit certificates in all the listed games are eligible for MBBS and engineering seats.

The bench said sports quotas were “inventions made for the purpose of diluting the constitutional guarantees granted to SCs, STs and BCs“, adding that they were also harming sports. “Ultimately, persons who gain admission into medical courses under this quota lose their flavour for sports..,“ the bench said.

Teachers’ training

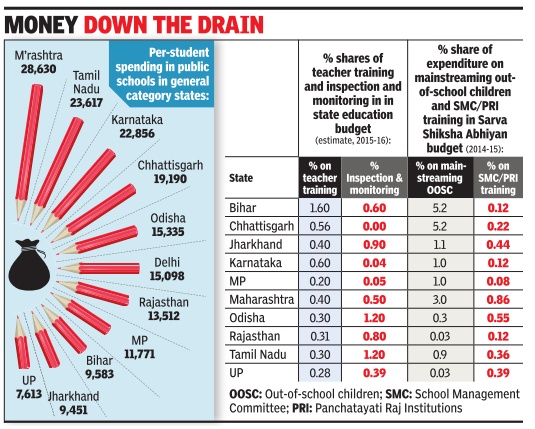

Study: States hardly invest in improving education quality, Dec 23, 2016: The Times of India

Just 1% Of Funds Spent On Training Teachers

For all the talk on education quality and improving learning outcomes, little is actually being done to achieve either.

The Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) and Child Rights and You (CRY) studied education budgets in 10 general-category states and found that allocations for measures, even statutory provisions for ensuring quality -teacher training, monitoring, community mobilisation and training -are close to negligible in education budgets. In fact, share of any of these categories rarely rises beyond 1% in the education or Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) budget in any state.

“There is much discussion on quality but governments are not investing in the systems responsible for improving quality,“ said Subrat Das of CBGA. The share of teachertraining in the education budget doesn't rise above 1% in any of the 10 states included in the analysis except Bihar, where it was 1.6% in 2015-16 (budget estimate).

Inspection and monitoring are similarly neglected with their share crossing 1% in on ly Tamil Nadu and Odisha, both 1.2%. The study considered all 12 years of schooling.While there is huge variation across states, per-student expenditure is less than that of relatively successful centrally-funded systems -the Kendriya and Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas (KVs and JNVs) -nearly everywhere.

More than 98% schools in the 10 states have formed school management committees (SMCs). Mandated by the RTE Act 2009, these are composed mainly of parents and community-members. In addition to monitoring the functioning of schools, the RTE also requires them to formulate school development plans and clear school budgets. But, again, states have spent very little on training them. The share of training SMCs and Panchayati Raj Institutions in the SSA budget was less than 1% in all 10 states in 2014-15.

Teachers' salaries do claim the largest chunk of the budget in all 10 states, ranging from 51.6% in Bihar to 80.4% in Rajasthan. But, as Protiva Kundu from CBGA said, “The myth that teachers' salaries take away all the funds for education is not true.“ State governments, especially UP and Maharashtra, spend significant amounts on non-government schools -as grants-in-aid and compensation for children enrolled in the 25% quota for Economically Weaker Sections and Disadvantaged Groups.

Education as a sector is under-funded, believe the organisations that authored the report. The per-student expenditure in public education in practically every general-category state is below that of KVs and JNVs.

Universal education

UN: India 50 years behind goals

The Times of India, Sep 06 2016

Manash Gohain

UN: India 50 yrs behind edu goals

India will be half a century late in achieving its universal education goals, according to a Unesco report released.This means the country will achieve universal primary education by 2050, universal lower secondary education in 2060 and universal upper secondary education in 2085. The 2030 deadline for achieving sustainable development goals will be possible only if India introduces fundamental changes in the education sector, the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) report says.

The report says over 60 million children in India receive little or no formal education and the country has over 11.1 million out-of-school stu dents in the lower secondary level, the highest in the world.

At the upper secondary level, 46.8 million are out of school, while 2.9 million students do not even attend primary school. The report says that by 2020 there will be a shortage of 40 million workers with tertiary education.

GEM report director Aaron Benavot told TOI, “Striving for development will mean little without a healthy planet. So, the new 2030 agenda for sustainable development unites global development and environmental goals.“

The report says 40% of students worldwide are taught in a language they don't understand. While the curriculums of half of the countries do not explicitly mention climate change, in India some 300 million students currently receive environmental education.

Women: Level of education

Women 68% of adult illiterates/ 2015

The Times of India Apr 09 2015

Kounteya Sinha

Women 68% of adult illiterates in country

The world is now home to 781 million illiterate adults with 68% of illiterate adults in India being women.

India has failed to reduce its adult illiteracy rate by 50% as planned and since 2000 on ly managed reducing it by 26%, according to a new UN ESCO global education re port to be launched on April 9 Even though there is good news with India expected to become the only country in South and West Asia in 2015 to have an equal ratio of girls to boys in both primary and sec ondary education, the bad news is that early marriage and adolescent pregnancies are keeping girls out of schoo in India. In 41 countries, 30% women aged 20 to 24 were married by the age of 18. As many as 36.4 million women in developing countries aged 20 to 24 reported having given birth before age 18 and 2 million before age 15.

India has the dismal record of having the highest absolute number of child brides: about 24 million. This represents 40% of the 60 million world's child marriages. India is also home to 225 million adolescents, consisting nearly one-fifth of the nation's total population. Around 16% of these girls -aged 15-19 -have already begun child bearing and 12% have had a live birth. The report had some good news for India -rural India saw improvement in nearly all aspects of school facilities and infrastructure.

Digital Gender Atlas for Advancing Girls’ Education, 2016, state-wise

The Hindu, December 17, 2016

Anuradha Raman

For poor families in rural Bihar, educating the girl child can be tough but a rewarding choice.

There is a well-known saying that if you educate a man, you educate an individual, but if you educate a woman, you educate a nation. In the order of national priorities, educating India’s girl child figures right at the bottom and she is more often engaged as extra help at home or as domestic help in others’ homes.

The Digital Gender Atlas for Advancing Girls’ Education produced by the Ministry of Human Resource and Development has ranked States and Union Territories from 1 to 35 based on several indicators ranging from enrolment to dropout.

According to the Atlas, Bihar’s dropout rate for girls is below the national average of 4.66 per cent. States with even higher dropouts are Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and a few more from the North East. Mizoram reported a staggering 23.93 per cent dropout rate among girls.

There are good reasons these States rank low in terms of literacy indicators. Sanjay Kumar of Deskhal, an NGO in Bihar, says that there is a two-pronged discrimination that girls face early on: one, from their parents and the other, from the teachers teaching in schools. The first shows up when parents send their boys to private schools and girls to government schools. The second level of discrimination takes place when teachers reinforce the belief that boys learn faster than girls, thus discouraging the girls.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2015 puts the proportion of dropouts in the age group of 6-14 at 3.9 per cent. Of this, 22 per cent boys and 24 per cent girls dropped out before completing Class I. However, the difference in dropout rates between girls and boys increases among 11–14 year olds, as girls are eased out of schools to work at home or get married. Two-thirds of those not in school were from the lowest castes, tribal groups and Muslim communities.

The government is spending on campaigns to protect the girl child and also pledging to educate her – Beti Bachchao and Beti Padhao – with ringing endorsements from Bollywood celebrities.However, less than 160 km from New Delhi, in a small village in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh, parents don’t want their girls to go to a school that is less than two kilometres from their home.

“There are louts on the way. Who will protect my girls when they get harassed on the streets,” asks a mother. That is one question that the state has to answer.

See also

Education: India (covers issues common to all categories of Education) <> Education: India, 1911 <> Engineering education: India <> Higher Education: India <> Medical education: India <> Primary Education: India <> School education: India (covers issues common to Primary and Secondary Education) <> Secondary Education: India <> Indian universities: global ranking <> Caste-based reservations: India …and many more.