Eliza Kewark

(Created page with "{| Class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> </div> |} [[Category:Ind...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[File: Katherine Scott Forbes or Kitty, the daughter of Theodore Forbes and Eliza Kewark; and Prince William.jpg|Katherine Scott Forbes or Kitty, the daughter of Theodore Forbes and Eliza Kewark; Picture courtesy: [http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

{| Class="wikitable" | {| Class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 14: | Line 16: | ||

=Armenians in Surat, Gujarat= | =Armenians in Surat, Gujarat= | ||

[http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013 | [http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013 | ||

| − | |||

Samyabrata Ray Goswami | Samyabrata Ray Goswami | ||

Revision as of 08:22, 5 December 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Armenians in Surat, Gujarat

The Telegraph, June 21, 2013

Samyabrata Ray Goswami

On the elusive trail of Eliza Kewark

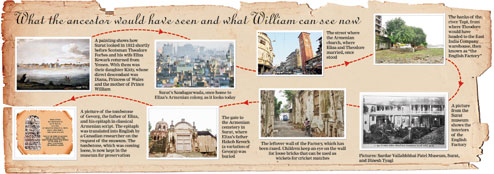

Prince William need not come knocking to Surat; his folks do not live here any more. The genetic needle that threaded his DNA to an Indian ancestor is more or less lost in the haystack of history.

But if he takes a stroll around the old city, perhaps among the oldest cosmopolitan pre-British urban centres in India, he might pick up a few old threads to spin a yarn about his multi-cultural genealogy.

There are no Armenians in Surat any more. Residents of the old city, largely small-scale textile traders, have long bought over their properties and razed them to build newer houses and trading markets.

But it is in the alleys of old Surat’s Saudagarwada (borough of merchants) that his mother’s Indian-Armenian ancestor, Eliza Kewark, lived a lonely life after her Scottish husband deserted her and died aboard a ship on his way back home to Aberdeenshire.

William’s mother Diana was a direct descendant of Kitty, daughter of Eliza and Scotsman Theodore Forbes.

Elenza Kewark in Surat

In a document written in 1937 and acquired by The Telegraph from St Andrews Library in Surat, eminent Calcutta-based Armenian historian Mesrovb Jacob Seth writes that Eliza, listed as Elizabeth Farbessian, was one of the last seven Armenians in the city after Forbes’s death in 1820. “Farbessian” was possibly an Armenian-style derivative of “Forbes”, a historian suggested.

It’s unclear whether Eliza died in Surat — there are no graves in her name in the city’s only Armenian cemetery in the Katargam Gate area.

Nor, if she migrated to Bombay where Forbes once worked, whether she did so with their son Alexander, who stayed on in India after Forbes sent Kitty away to Scotland in 1818.

Family

The last name is that of Eliza’s brother-in-law and Forbes’s Armenian agent, also known as Arrathoon Baldassarian.

“If he (Arrathoon) was married to her (Eliza’s) sister and they had a daughter, Prince William may find some cousins in India,” said Meghani.

Eliza’s last name has so far been mentioned as Kewark by British researchers based on her letters available with them.

“Kewark is a variation of Kevork after her Armenian father Hakob Kevorkian. He seems to have died in 1811. His tomb, in which he is called Gevorg — another variation of Kevork — was found in Surat’s Armenian cemetery and is now in the city museum cellar,” said Bhamini A. Mahida, chief curator of Surat’s Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Museum.

Eliza largely used Kewark as her surname in her communications with her husband or, later, his family.

“That she did not sign her name as Forbes or Farbessian indicates she did not have the legal sanction of a wife to use her husband’s name. But after Theodore’s death in 1820, she might have felt emboldened to use it in an Armenian way and call herself Elizabeth Farbessian.”

It may have helped that Forbes left her a tiny annuity in his will. He left substantial allowances for his children, with his daughter Kitty —Prince William’s ancestor — receiving the lion’s share.

“The allowance must have given Elizabeth some sort of social recognition, and she may have started using Forbes’s name,” Meghani said.

In perhaps an unwitting but cruel reminder of her status, Theodore referred to her as his “housekeeper” in his will. “It could be his way of avoiding public stigma for his family as Elizabeth had an Indian mother,” Meghani said.

The mother

British researchers say some of Eliza’s earlier letters to Forbes were written in Gujarati. Elizabeth’s Indian mother was likely to have been Muslim.

“Because of the Armenians’ closeness to the Mughals, it’s a possibility that she (Eliza’s mother) was a Muslim. Hindus would have been more unlikely to marry outside their caste,” Mahida, the archaeologist and museum curator, said.

The tombstone of another Elizabeth in Surat’s Armenian cemetery appears to bear this out. Her name is spelt “Eligabeth” in the epitaph — a typical Indian phonetic variation of the “z” sound, explained Mahida.

This Elizabeth died in 1784, at least six-seven years before Eliza Kewark would have been born. Her burial in the Armenian cemetery suggests her father or husband was an Armenian, given the strong patriarchal traditions of the community. Yet the name of neither is mentioned in the epitaph, written in the classical Armenian script.

“The inscription on the tomb names her as Eligabeth and mentions her as the daughter of Nazar Tilan, which is a Muslim woman’s name,” said Mahida. The tombstone with the epitaph is in the cellar of the museum.

British researchers say that Eliza Kewark and Forbes married in an Armenian church in Surat. Of the two churches the city once had, the one in the cemetery survives but the one in the old city, used mostly for weddings, does not.

Standing in its place are rows of ugly, four or five-storey buildings owned by local traders who run establishments on the road level and live and store their wares on the remaining floors.

The Bombay Armenian Cemetery has the tombstone of a Kevorg, a derivative of Kevork. He was buried in 1927, according to the church register. (Eliza’s father was Hakob Kevork or Kevorkian.)

“But no historian can say right now whether (Kevorg) was connected to Elizabeth or Alexander. The links, if any, are buried in the sands of time,” said Surat historian Mohan Meghani who has done extensive research on the city’s Armenians.

Armenian population, a decline

Seth, the Armenian historian, writes: “The decline and dispersion of the Armenians at Surat must have been very rapid.… During the last two decades of the 18th century (1780-1800), there were 33 (Armenian) merchants besides many others in the humbler walks of life.… Their numbers dwindled down to only (seven) souls in 1820. Their names were: Mrs Elizabeth Farbessian, Mrs Maishkhanoom Avietian, Mrs Mariam Vardanian, Stephen Petrus, Minas Margarian, Gregore Agahian and Arrathoon Balthazarian, the only well-to-do amongst them being the lady mentioned first.”

The warehouse

Jahnubhai Patel, who runs a zari business in the area, does not remember any Armenians but says his ancestors bought the home-cum-warehouse he owns from a Parsi businessman.

“There were many Parsis here then. The English Factory (a former East India Company warehouse-cum-house where Forbes once worked and lived) down the road was also owned by a Parsi businessman called Cooper who bought it from the British,” Patel said.

“We know this because his last descendant, who lived in the massive building all alone in the 1960s, was insane and broke down the place using a bulldozer as he was tired of researchers from India and abroad coming to his place regularly and requesting a tour of the premises,” recounts Patel.

Meghani confirmed the building’s razing by its “insane” owner.

“Prince William better come and collect the remaining bricks on this half-wall of the English Factory before the children of the adjoining I.P. Mission school take them away to use them as wickets in cricket matches on the school compound,” he said.

Called Saudagarwada even today, the area’s architectural character has largely changed, but demographically it still remains a predominantly merchant colony like it was when Forbes landed on the banks of the Tapi in 1809.

“As a young officer of the East India Company, he would have sailed in a boat down the Tapi from Suvalli, a British jetty near Surat, and landed on the riverbanks in the old city,” Mahida said.

The warehouse of the East India Company, where Forbes would have worked while in Surat, is a few furlongs from the Tapi’s banks. Today, destitute people and immigrant workers catch their afternoon nap on the river embankment by the English Factory, as the warehouse was called.

When The Telegraph visited the place, only a 12ft by 20ft, moss-laden, rundown wall of the “factory” stood. The remnants were in effect no more than a temporary boundary wall for an under-construction residential high-rise coming up where the warehouse once stood. Nothing else of it remains.

In Forbes’s time, the “factory” or warehouse was a two-storey structure of bricks and timber, said Meghani, quoting from a research paper on East India Company factories and facilities in Surat by Kyoto University’s Haneda Masashi.

“Masashi based his research on old Surat Municipal Corporation records before most of them were destroyed in a flood in 2006,” Meghani said.

While the ground floor was used as a godown, Forbes would have lived in the comfortable staff quarters on the first floor.

About 500 yards down the same street would have stood the warehouses of other European merchant companies, owned by the Portuguese, Dutch and the French. The Armenian settlement where Eliza would have lived began after that and the Armenian church would have been down the same street.

“The entire area would have had a radius of one kilometre. It would have been bordered by gardens, fountains and a red-light district from the Mughal era that existed in the old city till about a decade ago. Saudagarwada would have been a bustling place,” Meghani said.

Indian-Armenian marriages

Meghani said that marriages between Armenian men and Indian women were uncommon but not unheard-of around the end of the 18th century.

“The community had been settled in India for over 500 years by then and was seen as close to the Mughal throne and hence powerful. So, intermarriages would not have been terribly frowned upon,” Meghani said.

The romance

In such a “happening” place, buzzing with pretty local girls and dashing merchants and sailors, the romance of Forbes and Eliza would have blossomed.

“And for what it is worth, the relationship seems to have been more than a bond of convenience,” Meghani suggested.

Despite the accepted norm of keeping mistresses, did the 23-year-old Forbes love a 19-year-old Eliza enough to make her his wife? “It seems he tried,” Meghani said.

“If British researchers say he may have married her in the Armenian church, it would have been a very honourable thing to do given that if he had not, no one would have raised a finger,” Meghani said.

According to the records, Forbes, when posted to Yemen soon after, took Eliza, pregnant with his daughter, along.

“When the child was delivered in Yemen, he named her Kitty after his mother. By the time Eliza and Forbes returned to Surat, they had had another baby, Alexander. Later, she delivered another son, Fraser, who died after six months,” Meghani said.

“Although Forbes neglected the family after moving to Bombay, he did send a close friend, Thomas Fraser, another Scotsman, to look up Eliza in Surat. It was on Fraser’s suggestion that he sent Kitty to Scotland. He even mentioned his children and Eliza in his will. Does not seem like a scoundrel to me,” said Meghani.